Franco-Lebanese businessman Ziad Takieddine, 61, is cited as a key witness in ongoing investigations led by examining magistrates into suspected illegal political financing in France from the sale of three French Agosta class submarines to Pakistan in the 1990s. The magistrates' enquiry was launched after suspicions that the significant sums officially destined as commissions - or bribes - to Pakistani officials ended up returning, illegally, to France to fund political activities. Suspicion centres on former prime minister Edouard Balladur's political movement and unsuccessful 1995 presidential election campaign, for which his budget minister, Nicolas Sarkozy, also served as official campaign spokesman.

Several witnesses questioned by the magistrates have designated Takieddine as a key intermediary in the 1994 contract who was imposed on the deal by Balladur's government shortly before it was concluded. Balladur, Sarkozy and Takieddine have firmly denied knowledge of illegal political funding via the commissions.

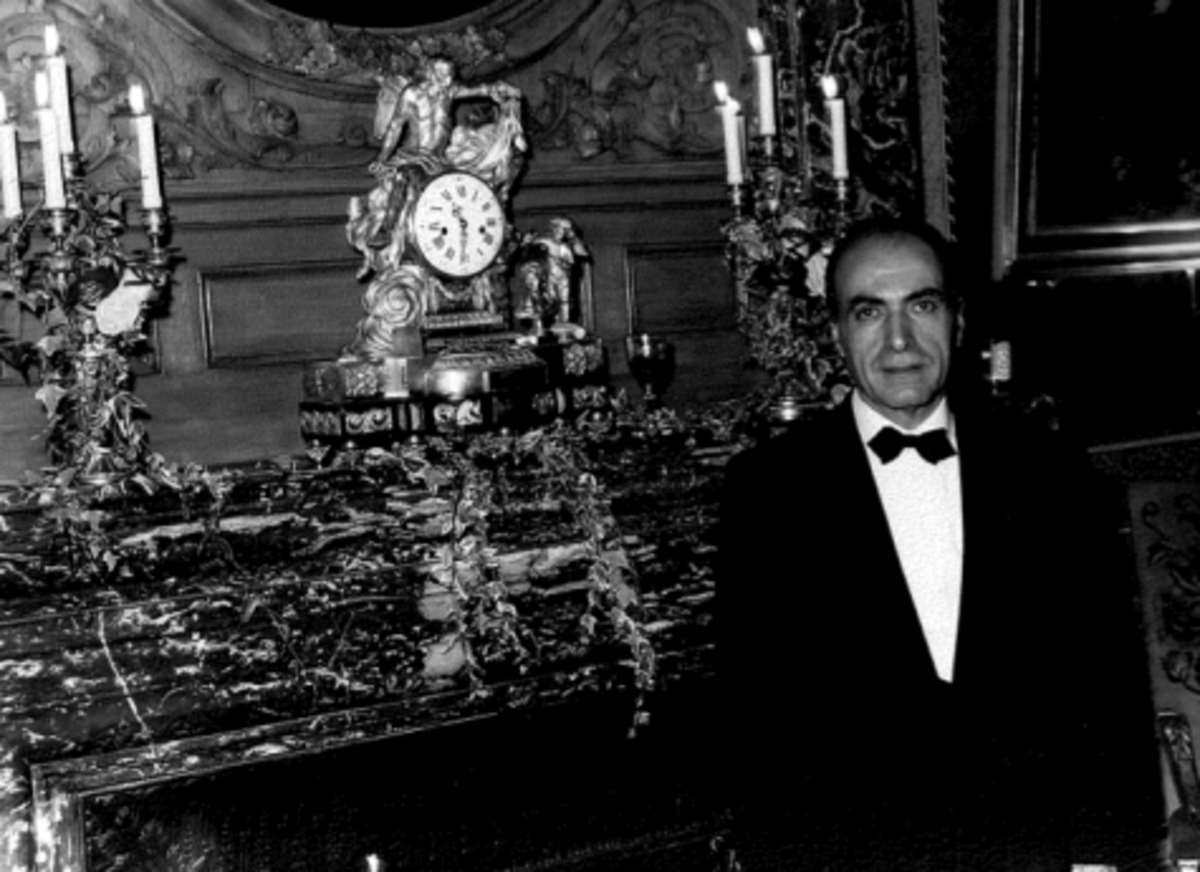

Written and photographic documents exclusively obtained by Mediapart and published in earlier reports in this series have demonstrated the very close and longstanding links, both professional and social, between Takieddine and Nicolas Sarkozy's immediate entourage. Mediapart has revealed how Paris-based Takieddine surprisingly pays no income nor wealth tax in France, his fiscal domicile and where, according to documents signed by him, his personal fortune has an estimated value of more than 40 million euros.

Mediapart has further disclosed how in 2003 Takieddine was destined to receive 350 million euros in secret commissions from another arms contract, this time with Saudi Arabia, negotiated on behalf of Nicolas Sarkozy's aides via a company run by the French interior ministry when it was headed by Sarkozy. Mediapart has also disclosed how the arms dealer, while negotiating that contract, was saved by Sarkozy's entourage after an alleged assassination attempt on the exclusive Caribbean island of Mustique.

The investigations have also shown how Takieddine served as a protector for Colonel Muammar Gaddafi's nephew Mohammed al-Senussi after he was charged in London with causing ‘grievous bodily harm' to two escort girls and how the businessman, backed by Sarkozy's Elysée Palace chief-of-staff, was paid almost 7 million euros by oil group Total in a gas field deal with Gaddafi's regime.

Today Mediapart can reveal the extent to which the French foreign intelligence agency, the DGSE (Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure), has sought to conceal what it knows about the businessman's activities, and how in effect he has himself become a state secret.

Examined in 2010 by the judges investigating the Karachi affair, who are looking into his role as middleman in the sale of the Agosta submarines to Pakistan, the DGSE kept a tight lid on all its information about the businessman's unofficial activity, according to documents and inside information recently obtained by Mediapart.

In a memo dated February 17th 2010, which was declassified at the end of 2010 - and subsequently exposed on the French news site OWNI - the French intelligence agency said it had "only old scraps of information about him dating from the 1980s, when Ziad Takieddine, then a Lebanese national, was working on behalf of Saudi Arabia's Al Amoudi group".

The agency's obliviousness to the activities and exploits of one of the most powerful middlemen in the world now appears blatantly disingenuous. Among other things, the DGSE has withheld the fact that Takieddine had proffered his services to the head of the agency, Pierre Brochand, in May 2005. In that letter, which Mediapart reveals here (see below), Ziad Takieddine undertakes to furnish "information relating to France's external security" based on "various meetings with Colonel Gaddafi in Libya".

At the time, Takieddine availed himself of the services of an economic intelligence company, Salamandre, on whose board of directors sat two ex-DGSE officials: ex-agency head (1987-1989) General François Mermet and ex-director of intelligence (1989-2000) Michel Lacarrière. According to Takieddine's letter to the DGSE, it was Mermet who had recommended him to then agency chief Brochand.

Documents now in Mediapart's possession indicate that Salamandre was paid 150,000 euros for consulting services to help French companies procure business in Libya. Salamandre advised the Bull group, for example, on the sale of its system for the encryption of Libyan regime communications, for which Takieddine's companies were paid 4.5 million euros in secret commissions in 2007 and 2008.

Takieddine requests face-to-face interview with DGSE chief

In the Karachi affair, the investigating magistrates have been waging a fierce and uneven battle against state secrecy for many months now. Last autumn, Justice Marc Trévidic asked the defence minister to declassify 54 documents. The minister referred the request to the Commission Consultative du Secret de la Défense Nationale (CCSDN, Advisory Committee on National Defence Secrets), which in December 2010 approved declassification of only 23 documents, including a truncated version of Ziad Takieddine's record.

The DGSE admits, as it says in Takieddine's file, that he "is known in France above all as an intermediary operating primarily in the arms markets on behalf of French companies", and that he has "a large network of connections" in France. Beyond that, the DGSE "has only old scraps of information" and, for the rest, confines itself to citing two articles from the press.

Those two articles date from 2004. And the only political connection ascribed - "by the press" - to Ziad Takieddine goes back to 1994 and concerns defence minister at the time François Léotard. There is not a single word about his extensive contacts, revealed by Mediapart in previous articles in this series, to Sarkozy's men Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres, Brice Hortefeux, Claude Guéant and Jean-François Copé.

The DGSE is not the only body to keep the Takieddine connection under wraps: the CCSDN defence secrets watchdog plays a part here as well. This past April, the CCSDN refused the request of Justice Renaud Van Ruymbeke for the declassification of the so-called "DAS II Bis" tax returns of Thomson and Sofresa, two companies implicated in the arms sales to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. These tax returns - which were discontinued in 2000 after the OECD adopted "anti-corruption instruments" - should in theory show the amounts of the commissions as well as the names of the intermediaries and the foreign political authorities that purchased the arms in question.

If the name Ziad Takieddine, the main go-between for the deals that were clinched in 1994, crops up in the tax documents, it must also figure somewhere in the DGSE's files. Under the authorisation procedure of the French arms export control board (CIEEMG), to which the frigate and submarine sales to Saudi Arabia and Pakistan were subject, the DGSE was supposed to vet the probity of the deal-makers. So the agency's record of February 17th 2010 looks like a gross case of window-dressing. Nor is it surprising that the DGSE should also conceal the extent of its own connections, whether direct or indirect, to the businessman - as well as his offer to work for the agency.

In May 2005, Ziad Takieddine took out a sheet of stationery - whose letterhead shows his prestigious Parisian address (nonetheless concealed from the French tax office) in the avenue Georges-Mandel - to write to Pierre Brochand, who had been DGSE head since 2002 (see letter below). He claims it is "on François Mermet's advice" that he is "directly contacting" the secret service chief. His object is to communicate, "in person and face to face, information relating to France's external security" based on "various meetings with Colonel Gaddafi".

That missive now puts Takieddine's sponsors in a tight spot.

Takieddine walked around saying, “I’m Sarkozy’s special envoy.”

"That doesn't ring a bell to me," was François Mermet's reaction when Mediapart asked him about this letter to the secret service. It turns out that the former DGSE chief first established contact with Ziad Takieddine through the mysterious Salamandre company, where Mermet served on the board of directors.

At the time Salamandre was looking into American interests in Gemplus, a French manufacturer of smart cards, in which Takieddine held a minority share along with Thierry Dassault [a specialist in economic intelligence, son of French arms industrialist billionaire Serge Dassault]. "The Gemplus business was clean," says General Mermet. "But he wanted to do other operations that were less so."

"I always considered Mr Takieddine the kind of guy you didn't want to be associated with - and that you had everything to lose if you were," says former DGSE director of intelligence Michel Lacarrière. "I know he wanted to see the head of the DGSE and that he wasn't very well received. This gentleman acted important and meddled in a whole bunch of stuff."

Actually, Ziad Takieddine got the Salamandre company closely involved in his Libyan projects. Between 2005 and 2006, Salamandre's CEO Pierre Sellier, likewise reputed to have close ties to the secret service, literally seconded Takieddine in his efforts to contact French industrialists and steer them into Libya. The magnates rallied to two flagship projects, which are covered in a previous Mediapart article : to help Sagem land a contract to renew Libya's air force fleet and to help the Bull group sell encryption systems to protect the Libyan regime against the West's Echelon communication intercept network.

And while they were at it, they contemplated setting up a Franco-Libyan think tank (see letter below), with François Mermet and Michel Lacarrière serving as distinguished members and Salamandre's president as "secretary-general (logistics treasury operations)".

Though the Bull deal did indeed come through, the think tank idea came to nothing, and the Sagem scheme met with resistance from industrial circles and from a top-tier intelligence official: viz. Alain Juillet, economic intelligence advisor to the Secrétariat général de la défense nationale (SGDN, Office of the Secretary General for National Defence), then at the prime minister's office; Juillet also served as head of intelligence at the DGSE from 2002 to 2003.

"Takieddine had been to Libya and he had started up a project with Sagem to completely overhaul the Libyan air force, whereas the French industrialists had agreed on reconditioning nine Mirages," Alain Juillet explained to Mediapart. "The industrialists had an interest in selling Rafales, which was jeopardised by the arrival of Takieddine. So I called together all the French operators and Mr Takieddine and I banged my fist on the table."

During that meeting with Alain Juillet in January 2006, Ziad Takieddine made a final plea for the idea of a "contract ten times as big" as a contract to merely get the Mirages airborne again. The Libyans, Juillet concedes, "never showed the slightest interest in the Rafale" and demanded "a complete upgrade of their aircraft".

"Considerable pressure was brought to bear at the time because the stakes were high. If he had clinched a complete overhaul of the Libyan fleet, that meant a lot, a lot, of money," added Alain Juillet. "Salamandre, whose board of directors included General Mermet and Mr Lacarrière, were undeniably working with Mr Takieddine. There's no doubt about that. At one point in the Libyan business, Salamandre were seen together with Takieddine."

Naturally, this Libyan battle could not have eluded the DGSE. But that too was withheld from the investigating magistrates. "For a long time Takieddine walked around saying, ‘I'm Nicolas Sarkozy's special envoy,' which was very questionable," recounts Juillet. "But Takieddine was a well-known middleman, and one who played an important role for a number of companies, for which he got very well paid. Companies are not philanthropists: when they pay, then it's because they have reasons for doing so."

On Tuesday, August 23rd, a spokesperson for the DGSE - which is currently headed by Erard Corbin de Mangoux, ex-director general of services for the Hauts-de-Seine region from 2006 to 2007, then adviser to President Nicolas Sarkozy - told Mediapart that the agency "generally doesn't comment on matters of this kind". He added:"The magistrate has been told what we know." His predecessor Pierre Brochand has not responded to Mediapart's messages.

-------------------------

English version by Eric Rosencrantz