The Paris suburb of Le Blanc-Mesnil is typical of dozens of socially-deprived agglomerations that surround the capital’s northern perimeter, characterized by zones of high-rise public housing estates and significantly higher than average unemployment, especially among the young.

The French word for suburb – banlieue – has become a symbolic term of description for these run-down urban areas which circle most major cities across France and which were the scene of major riots that erupted in 2005. Le Blanc-Mesnil, with a population of 51,000, was one of them.

The banlieues typically housed large numbers of immigrant, and mostly North African, workers’ families in the sprawling and soulless housing projects that mushroomed during the boom years of the 1960s and 1970s. The legacy of the subsequent steady economic decline in many of these areas, such as in the Seine-Saint-Denis département (equivalent to a county) in which Le Blanc-Mesnil sits, is an increased marginalisation of their populations, especially among the young, trapped in sink estates with ever-declining prospects of breaking out of a spiral of joblessness and low living standards.

The stigmatization of the inhabitants of the banlieues was one of the frustrations voiced during the notorious 2005 riots. But these and continuing incidents of unrest and violence have reinforced a stereotyped image perceived among the broader population of almost lawless zones ruled by disenfranchised, feral youths whose parents, of North or West African ethnic origin, are either incapable or uninterested in containing. Added to this, the mounting anti-Muslim sentiment among a part of French society has deepened the alienation and tensions.

It was within this context that the Blanc-Mesnil town hall launched a project to give voice to a representative section of its population, whose real lives and day-to-day experiences are rarely revealed to the wider public, save for the lyrics of rap music or news reports of gang violence or hooliganism.

Over a two-year period, a group of almost 30 women aged between 30 and 75 years old, some of French nationality, others not, but all of North African origin, met together once a month to share their observations and anecdotes about their everyday experiences of life in Le Blanc-Mesnil, and notably the discrimination many feel they and their families are subjected to. Their meetings, in a local events hall, were organised by the director of the town hall’s anti-discrimination department, Zouina Meddour, and a sociologist, Saïd Bouamama.

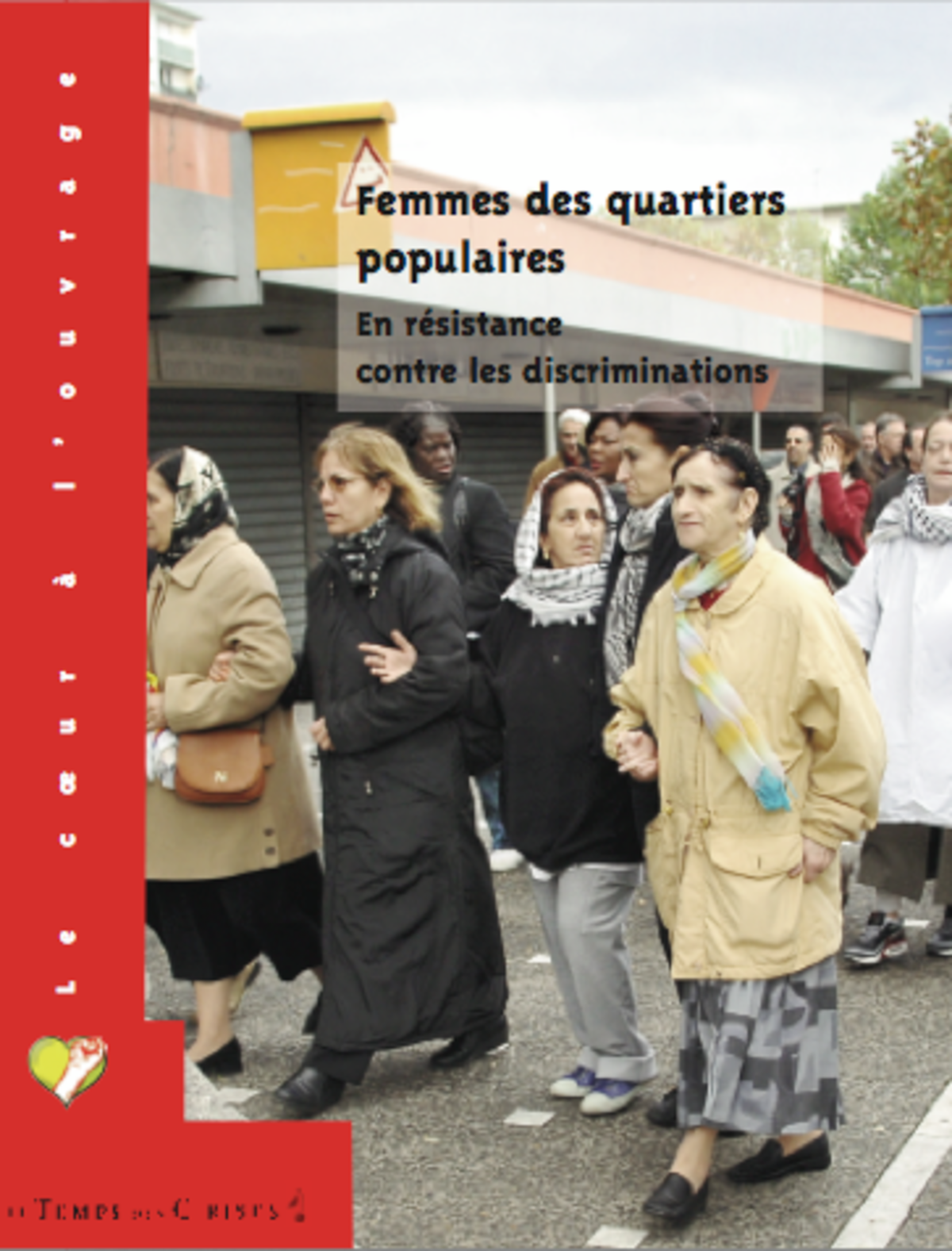

A selection of their recorded individual contributions and collective comments is the basis of a book published in France last month, entitled Femmes des quartiers populaires, en résistance contre les discriminations (‘Women from lower-class neighbourhoods, mounting resistance against discrimination’). The vibrant texts offer a colourful insight into life within the suburb, one which dismantles many prejudices held on the outside.

“It is so rare these days for the inhabitants of lower-class neighbourhoods to be given a voice,” commented the mayor of Le Blanc-Mesnil, Didier Mignot, in his preface. “It is most often confiscated to the benefit of media representations which [produce] rigid identities and hide the everyday reality of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants.”

The women’s first names include Houria, Zohra, Zineb, Jamila and Fatiha, but also Mylène, Martine and Mallory. Some wear the Muslim veil, others not, some are married with families, others are single parents, and there are also retired women. While some complain of constant discrimination, another explains how she has never suffered any prejudice, probably because of her blonde skin and hair.

They complain of being characterized by an image of “feeble beings, submissive victims with a low educational standard and on the margins of society”, whereas, they say, “we battle every day, within our families or our neighbourhoods, and we are active and engaged in our [local] society”.

One of the group talks of her frustration at perceptions of Muslim women. “[There are those who] want to dictate to us how we dress,” she says. “That I wear a miniskirt or the veil should be my personal business. I don’t wear the veil but they must stop saying that those who do, it’s because of the pressure of fathers or brothers. This picture is really injurious for us. It’s as if we were passive and incapable of defending ourselves. It’s once again the picture of the submissive woman, that’s to say a prejudice about Arab or Muslim women. It suffices to know the daily life of an Arab, Berber or Turkish family in Le Blanc-Mesnil. Our daughters don’t let themselves be had. They defend themselves, they aren’t submissive. They have a brain with which to think and a mouth with which to express themselves.”

'Insufferable' and 'violent' prejudices

They discuss their experiences as mothers, as job seekers or hunting for a flat, their dealings with their children’s schools, with the police, the social security administration, and relationships with shop-keepers or incidents at the Post Office. They talk of incidents of discrimination against themselves and their families and question the reasons for such events. Should they feel a part of responsibility, as some political figures suggest? Are they responsible for the treatment dealt out to their children? Is their culture to blame?

They readily recognise the extent of violence among a section of the youth population in Le Blanc-Mesnil, such as the shooting dead of a teenager during a 2009 gangfight, the high number of school drop-outs and the degree of academic failure among the young, the widespread drug dealing and the problems of alcoholism.

But they argue that these problems are the consequence, and not the cause, of the economic and social misery that surrounds them. They denounce the structural inequalities of the suburbs like their own, referring to a July 2012 report by the French national audit office, the Cour des comptes, which found that the banlieues receive on average, by inhabitant, the lowest amount of public funding for urban areas.

“There is a constant need to juggle around in order to have something to put on a plate or to properly clothe the children,” they complain. “Normally, Christmas is a moment of pleasure but we don’t manage that anymore. As soon as we have paid the bills, there’s nothing left in the account. In our neighbourhood, there are lots of isolated mothers and for them it’s a catastrophe. We do without everything so that the children have the minimum. We can’t always say ‘no’ to them.”

One collective comment was about the state of the local streets where “you’d say there’d been a war there.”

“They’ve bricked-up the empty shops to avoid squats being established. They’ve settled the matter with bricks and cement without worrying about the consequences for us. Frankly, what image does that leave us and our children with? We sometimes have the impression of being plague carriers when you see these walls every day.”

They cite the local Post Office as an example of how the banlieue is treated with disdain. “We had to campaign for an enlargement of the premises [of the Post Office] and when it reopened they reduced the opening hours […] But we’re not ignorant and stupid. We have to compare with what’s said and done elsewhere. For example, in Paris the Post Office runs an ad campaign about the increase in opening hours ‘to adapt to the rhythm and hours of working people’. It’s presented as the proof that the Post Office respects its users. So what about us, are we not respectable?”

One of the group describes an experience with her General Practitioner. “This happened to me recently,” she recounts. “I was at my wit’s end and the doctor gave me…one day of sick leave. On top of what I was already living through, I had to put up with being taken for a liar. I got the impression that for that doctor you had to be more resistant being a Maghrebi. Unless he thought that behind every Maghrebi was a hidden fraudster. We are like all the others. We’re neither supermen nor superwomen. This feeling of being treated differently is insufferable and very violent. It’s as if the Maghrebi or the Black didn’t have the same body, the same head and the same needs as all the others.”

'Politics has abandoned them, not the reverse'

They speak often of how residents pull together to overcome everyday problems. “Fortunately there is mutual help,” comments one of them, “but even that is becoming difficult. When we need something we knock on the neighbour’s door. We help each other with a piece of butter, a carton of milk, an egg or something else. The other day a neighbor knocked on the door to be helped out, I can’t even remember what it was for. What surprised me was the reaction of my girls. They said to me ‘Mum, we’re poor too, we can’t always help others’. We still keep helping but it’s more and more difficult. But mutual help, however, is all that we have left. It’s the richness of the poor.”

They recall how, during the riots in 2005, mostly involving local youths, a crowd of mothers demonstrated their anger outside the very same events hall used now for their group meetings. They succeeded in organising a subsequent debate about the unrest and its causes, held amid a full house of local residents but without local political representatives, despite invitations for them to speak.

“It’s erroneous to say that the lower social classes don’t interest themselves in politics,” the women note in a collective comment. “We think that, quite the opposite, it is politics today that are not interested in them.”

Together they call for all foreign nationals resident in the suburb to be given the right to vote in local elections, where currently only French citizens and EU nationals are allowed to take part. This, they argue, is an indispensable move to allow the inhabitants of France’s banlieues to properly make their opinions known.

-------------------------

- Femmes des quartiers populaires, en résistance contre les discriminations is published by Le Temps des cerises, priced 14.25 euros.

-------------------------

English version: Graham Tearse