France has reached an unprecedented housing crisis, with an estimated 3.6 million people living in inadequate or substandard housing while the country lacks some 900,000 accommodations in the publicly-managed ‘social housing’rented sector. That was the dire message of the latest yearly report released earlier this month by the Fondation Abbé Pierre pour le logement des défavorisés, ('The Abbé Pierre Foundation for Housing of the Needy'), one of France’s leading charitable organisations dedicated to improving housing conditions for the poor.

"The figure of 1.2 million people on waiting lists for social housing in France, taken with the figure of some 3.6 million living in poor housing conditions, means there is no more room for procrastination: more accommodations must be provided," said the report published on February 1st.

The highly-respected foundation, whose board of governors include representatives from the ministries of housing and the interior, called on candidates running in this year’s French presidential elections, held over two rounds beginning in April, to commit themselves to what it called a “social contract” for a new housing policy. This would have four main projects building enough dwellings at accessible rents wherever a need is identified; regulating housing markets and controlling the cost of housing; perpetuating greater social justice and solidarity; and basing construction in urban areas on principles of equity and sustainability.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

While the shortage of low-cost social housing and high rents in the private sector are far from recent problems, politicians have so far failed to address the problem in any significant manner. Despite many, consistent warnings of a growing housing shortage, things have notably worsened over the past decade to reach what are now record figures.

The foundation said it is a major cause of social exclusion experienced by the poorest households, and has also caused "collateral damage" among the middle classes since the economic crisis that began in 2008.

"France is seeing significant demographic growth – population forecasts have been revised upwards – and an even stronger rise in the number of households due to factors such as marital separation, recomposed families and longer life expectancy. This means housing needs are constantly increasing," said the report.

While every candidate in this year’s presidential elections agrees that new constructions are needed to meet the crisis, their proposals on how to go about it diverge. "Why are prices rising?" President Nicolas Sarkozy – who has still not officially declared himself as a candidate for re-election – said in a televised interview at the end of January. "Because there is not enough accommodation, because there is not enough new building."

Sarkozy’s answer is to increase by 30% the current allowed ratio of the surface area of a building, or buildings, to be constructed on a given plot of land, and proposed that property owners be allowed to increase the size or height of their existing properties, the latter drawing sceptical reactions from housing associations and property professionals.

Socialist Party candidate François Hollande said that, if he is elected, his programme was "that 2.5 million intermediary, social and student dwellings would be built during the five years of the presidency," which he said represented 300,000 more than the total that has been built during the current presidency.

Hollande’s proposal includes financing the building of 150,000 very low rent public dwellings by doubling the ceiling on a government-regulated bank savings account, called the Livret A. This savings account, which carries an interest rate set by the government, currently has a ceiling of 15,300 euros.

The Front de Gauche, an alliance between a left-wing breakaway movement from the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, proposes to build 200,000 public housing dwellings per year over the next five years by increasing the Livret A ceiling to 20,000 euros. Its candidate, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, would also introduce a "housing contribution" tax of 10% on financial revenues.

The programme advocated by Green party Europe Écologie-Les Verts is to build 500,000 dwellings per year, of which 160,000 would be in social housing. Such a level of housing starts has never been seen before in France. It would be funded by reforming Action Logement, which levies a contribution from companies of almost 1% of their salary costs to finance building rental accommodation and other housing-related missions, as well as by the Livret A and an unspecified amount of public financing.

Public housing builds set to fall

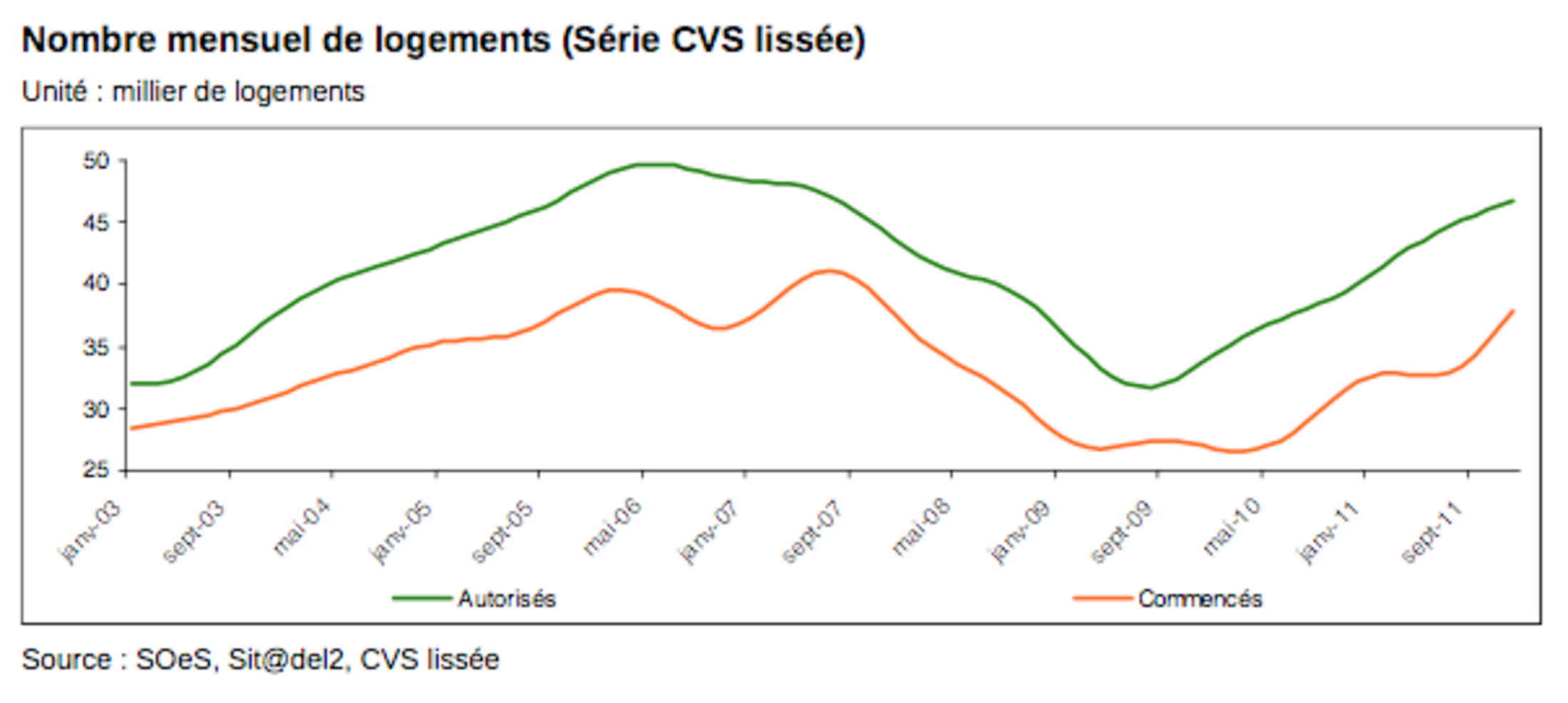

Meanwhile, the present government is taking credit for having already set things in motion. Housing minister Benoist Apparu said at the end of January that the reforms enacted by the government had allowed the construction sector to have a "very dynamic" year. His ministry released figures showing a 22.2% rise in the number of housing starts in 2011 to 378,561 units (available in French here).

The previous week the ministry had already reacted to Hollande’s proposals on social housing with a statistical report which said that 124,000 new social housing dwellings were completed in 2011, the largest number for a decade.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The Fondation Abbé Pierre recognised this progress, which it attributes in part to a plan for social cohesion brought in by former employment einister Jean-Louis Borloo, from 2005 to 2009, to promote employment, housing and equality of chances.

But the foundation’s director, Christophe Robert, noted that "the increase in the number of dwellings mainly concerns intermediary PLS housing [a category of social housing] which is not accessible to the 1.2 million households waiting for social housing for reasons of [their financial] ressources." (1)

Besides this, the rise in public sector housing starts mostly came from contributions made by local authorities and builders of subsidised public housing, known as HLMs (2), provided by their own capital to compensate for a fall in financial support from the government. State housing aid has focused on the individual rather than on building, the Fondation Abbé Pierre report said.

And despite a significant rise in new housing starts since the crisis of 2008, the association noted that the number of housing starts remains well below estimated needs. What should be done, it adds, is to "distribute housing starts so that they correspond to demand, and to do that, access to at least 60% of such dwellings should be based on income criteria."

This is critical because, the report underlined, "it is likely that construction of social rented housing will weaken from 2012" because of a variety of factors: no further boost from the plan for social cohesion which ended in 2009; uncertainty over the national urban renovation programme; questions over the future of Action Logement; and an expected pull-back in investment in building for private rental with the abolition of tax breaks (3).

Such a slowdown could affect the entire housing sector. Michel Mouillart, economics professor at the University of Paris-Nanterre, recently told news agency AFP he expects new housing starts to fall at least 10% in 2012 to between 330,000 and 340,000 units, and this trend "should continue in 2013".

Given that everyone agrees there is a housing shortage, the question begs as to why no housing policy has ever managed to bridge the shortfall, which has been steadily worsening over much of the past 30 years.

Fondation Abbé Pierre director Christophe Robert blames a lack of political will. "But over the past few years people have become more aware of the subject and it has been discussed more," he told Mediapart. "Some urban conglomerations like Montpellier, Rennes or Nantes have begun to take the problem on board, making land available and setting up the appropriate governance structures."

The foundation cited the example of Greater Lyon in its report, saying annual new house building there had doubled overall in the past ten years and, within this, social housing had tripled and the number of dwellings reserved for the most needy had been multiplied by just over three.

But in the most economically dynamic regions, chiefly in the Ile-de-France (Greater Paris) region and the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Rhône-Alpes regions in the south, house building has lagged behind seriously, said Robert. "It takes time to build, it cannot be done just by clicking your fingers. It requires an ambitious policy that has effects over several years."

-------------------------

1: The various categories of social housing in France are defined by income ceilings applied to applicants. See this web page, in French. Intermediary housing is aimed at middle class families. For a definition of PLS click here.

2: HLM, or Habitation à Loyer Modéré, is subsidised housing, usually in large housing estates (see here and here). It may be run by public or private bodies.

3: The Loi Scellier, brought in under President Nicolas Sarkozy, allows property owners to exempt 25% of the price of buying residential property from tax if the property is rented out for nine years. This tax break has been abolished from end-2012.

'The problem is distribution, not numbers'

While experts point out there are a number of obstacles which can prevent efforts to boost housing starts from being successful, politicians rarely address this level of detail, preferring to focus on targets for new building. "The overall number of dwellings to be built does not tell you much. You can produce a lot and get it completely wrong," said Vincent Renard, an economist specialising in housing and property markets at French national scientific research institute, the CNRS. "That was notably the case in Ireland and Spain where there was a lot of building, but where the housing crisis is now worse than it has ever been. What needs to be done is to regionalise supply."

Renard blames governance problems for the shortfall in new building. "A lot of mayors do not want to build for fear of antagonising their electorate, and they do not deny this," he told Mediapart.

To overcome this obstacle, the Fondation Abbé Pierre advocates giving more autonomy to local authorities with pro-active policies for housing and allowing government departments to act where local authorities are reluctant to move forward, either by offering them incentives, by imposing constraints on them or by substituting for them.

It is also necessary to offer clear visibility over time to all the players including those involved in building, the foundation said.

This idea of decentralising action in the public sector is taken up in ecology candidate Eva Joly’s programme. "Urban communities need to become the organising authorities for housing, with increased powers," it says. This would include "setting up regional land authorities and guaranteeing an equitable financial adjustment between regions."

And there is also an echo to this in a proposal from within the government, revealed by French daily Libération on January 18th, although Sarkozy curiously made no reference to it during his television interview at the end of January. The newspaper published a document prepared for a government meeting on January 13th which outlines changes envisaged in town planning by local authorities. Where there was an area under pressure for housing supply, urban planning would no longer be managed purely by each local authority but collectively by the local authorities in affected areas.

Another problem that remains unsolved is land availability, according to Vincent Renard of the CNRS. "We must free up land and set up a fiscal policy to do so," he said. "François Hollande’s proposal to make government-owned land available is a good thing. But it would need to be accompanied by a change in the tax regime for building land and with real plans for urbanism with deadlines."

It is critical to focus on the rental market, according to Jean-Pierre Lévy, a researcher in geography at CNRS. "It is above all necessary to review the problem of rented housing," he said. "We have mostly been building to provide access to property, but what is needed is to work on the pressure in the private rental market to free it up."

"The problem is not construction but distribution," he added.

The solution appears to be found not in focusing on figures, but in a complete overhaul of housing policy. Unless this is done, a drive to build at all costs could well produce the opposite of the desired effect, warned the Fondation Abbé Pierre. "Boosting construction and selling at high prices can sometimes lead to an overall price rise and a scarcity of low-cost housing," said its report.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version: Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)