They were two murders committed on the same day. One was that of a young employee of a refuse collection firm shot down by four hooded attackers as he arrived at work in the La Ciotat district of Marseille on September 5th. The other was a 30-year-man gunned down by two men on a scooter near the Frais-Vallon metro station in North Marseille's 13th arrondissement. But it was the second of these two killings, the 13th so called tit-for-tat murder recorded this year in the Marseille area, that grabbed the headlines. For the victim was Adrien Anigo, son of José Anigo, the sporting director of one of France's top football clubs, Olympique Marseille, a young man who was due to appear in court with two others accused of a dozen jewellery thefts in 2006 and 2007.

The impact of Anigo's murder – coupled with the other shooting – was almost instantaneous. After a summer of headlines devoted to crime in Marseille, the omni-present interior minister Manuel Valls made contact with the opposition UMP mayor of Marseille, Jean-Claude Gaudin, before announcing a “national pact...with all elected representatives” to “give back hope to the people of Marseille”. The following day the prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault joined the debate, calling for an “extension” of the “battle against drug dealers, against those who run an underground economy, who live off it, and who, when they divide up the territory, end up killing each other”.

So it was that the city's Members of Parliament, regional representatives plus the controversial socialist president of the Bouches-du-Rhône département council Jean-Noël Guérini – whose presence caused a stir, as he is under formal investigation for a number of alleged offences including peddling influence and unlawfully profiting from public office – gathered for an urgent round table meeting on Saturday morning with the region's prefect Michel Cadot and the head of the police in Marseille Jean-Paul Bonnetain. It was, however, more of a symbolic meeting designed to put an end to the political war of words fuelled by the closeness of the Socialist Party primary contest to choose its candidate for next spring's elections for Mayor of Marseille, and of nationwide local elections scheduled for the same time. Indeed, the only concrete announcement at the televised outcome of the meeting was that of an unspecified number of police reinforcements “between now and the end of the year”, to add to the unit of CRS riot police and 24 additional detectives already announced on August 20th.

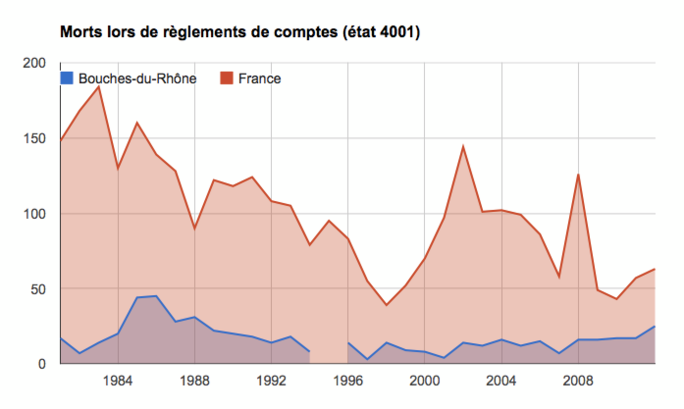

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In truth the initiative was another example of how, at regular intervals, France seems to rediscover the fact that tit-for-tat killings take place in Marseille. These are genuine ambushes carried out in the middle of the city in public places – bars, local offices and the street for example – by heavily armed attackers who hide their appearance. Yet while these gruesome incidents are undoubtedly spectacular, it is wrong to think that the number of such killings has suddenly jumped in the Bouches-du-Rhône, the area that includes Marseille, in 2013.

In 2012, for example, the police authority had recorded 19 such murders by the same period, compared with 13 this year (though the news agency AFP says the number is 15). “There's a recent tendency for the media to put each score-settling killing on the front page, so that one has the feeling that Marseille is becoming more and more dangerous,” says Cyril Rizk, in charge of statistics at the crime and sentencing monitoring unit the Observatoire national de la délinquance et des réponses pénales (ONDRP). “Yet while there was a very clear peak in 2012 [editor's note with 25 such killings in the whole year] for years the figures have remained at a hard core of around 15 deaths a year in the Bouches-du-Rhône. Even the 2012 peak does not signify an underlying trend: a succession of disagreements between two gangs can be enough to make the number of tit-for-tat killings go up sharply.”

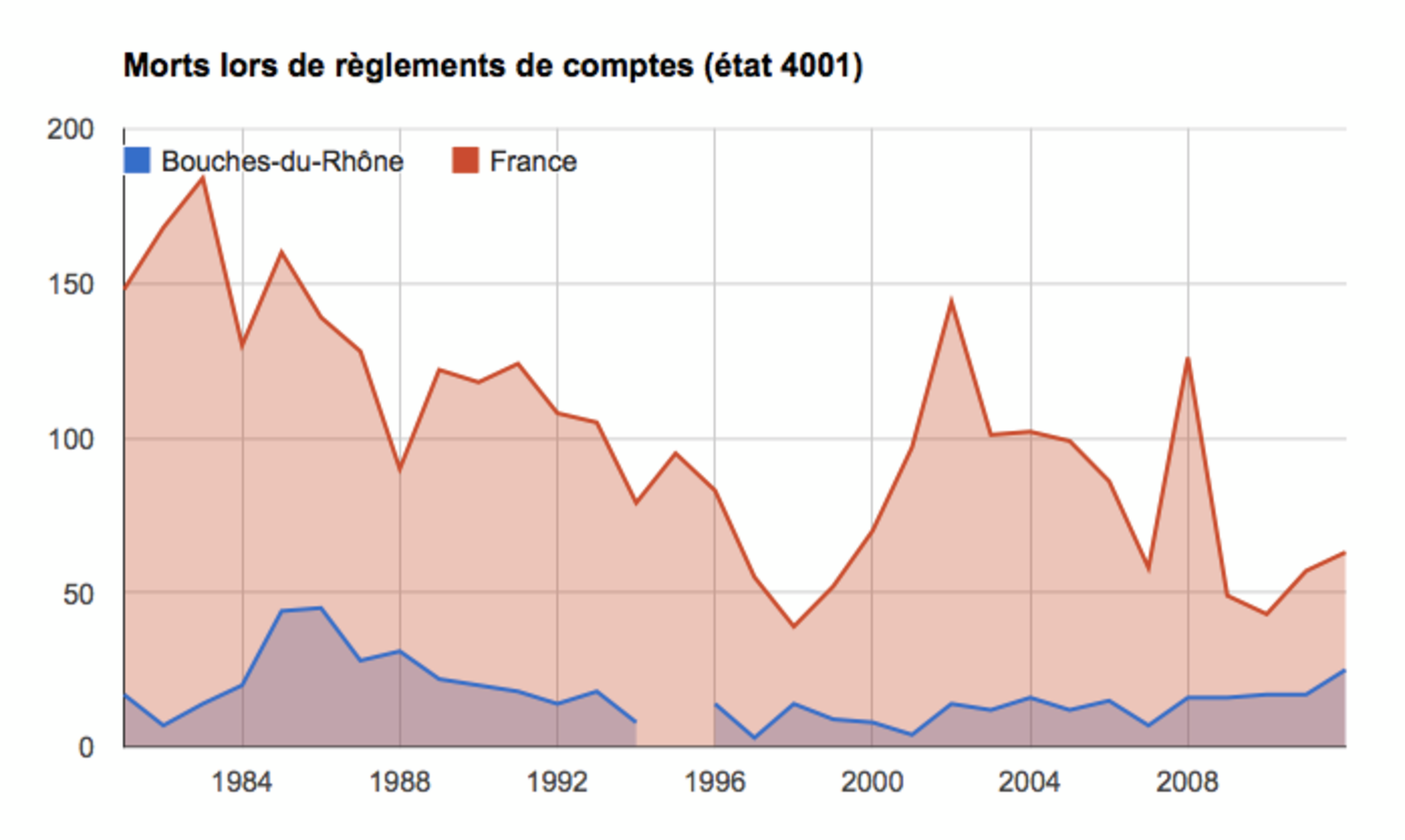

Enlargement : Illustration 2

To get a clear picture of what is really going on Mediapart has researched and compared the figures recorded by the authorities for the number of tit-for-tat murders in France in general and the Bouches-du-Rhône in particular. Contrary to popular thought, the figures show that the 1980s were far bloodier than the 2000s. The idea that criminals in the past had a “code of honour” appears to be just a myth. In 1984 and 1985, at the height of the war between the gang led by Gaëtan 'Tany' Zampa and that led by Francis 'The Belgian' Vanverberghe, the police and gendarmes recorded 44 or 45 deaths as a result of reprisal attacks in the Bouches-du-Rhône, most committed outside of Marseille itself. “And one can double that number, because the number of widows who were dissuaded from making an official complaint about missing victims is not counted,” adds Thierry Colombie, an academic specialising in the study of large-scale gang crime.

'No golden age of crime gangs'

“People talk about the times when organised crime played the role of justices of the peace and kept areas under control,” said Jacques Dallest, the former public prosecutor for Marseille, speaking at a December 2012 conference with the evocative title 'Marseille, the most crime-friendly city in France?' He continued: “But I don't think there was a golden age of great organised gangs. It's not true, you just have to read the awful things in the press from 30 years ago.” Marseille barrister Frédéric Monneret, who once defended Francis 'The Belgian', agrees it was worst in the past. “A comparison of the statistics shows that there was much more violence in the 1970s, 1980s and just into the 1990s, when rival gangs fought against each other,” he says. “In 1978 the Bar du Téléphone killing [editor's note, in the city's 14th arrondissement], that was ten people [killed]. In 1973 the [Bar du] Tanagra killing, that was four deaths in one go.”

Since 1985 the number of tit-for-tat murders recorded by the authorities in the Bouches-du-Rhône has slowly declined, reaching as few as three in 1997. Since 2002 the number has been around 15 people killed a year; admittedly still an enormous figure for a département – roughly equivalent to a county – of 1.9 million inhabitants. Only Corsica, which has around 15 tit-for-tat killings a year in a population of 305,000, is worse. “It's a kind of crime that is very concentrated in the area,” confirms Cyril Rizk.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Indeed, figures collated by the police and gendarmes show that in 2012 the Bouches-du-Rhône and Corsica accounted for nearly two thirds of all tit-for-tat killings in France. In the same year the authorities recorded five murders of this type in the wider Paris region of Île-de-France, which has 11.9 million inhabitants. In Paris, it is true, the troubled run-down estates are in the outskirts of the city rather than in Paris itself, unlike in Marseille. But even when the Paris suburb killings are taken into account the situation is far from being on the same scale as Marseille.

According to Jacques Dallest's estimate, roughly three-quarters of the tit-for-tat killings are linked to general crime on the run-down housing estates and a quarter to organised gangs. Some of the reasons often giving for the killings are disputes over drugs corners or “points of sale” that are more scattered and less lucrative, and the desire of youngsters to “rise up” the ranks more quickly. “The incidence of settling of scores in the drugs market is only possible...in a disorganised, competitive market full of small and relatively short-lived outfits,” wrote Gilbert Cordeau, a researcher who compiled a thesis on tit-for-tat murders in Quebec, in 1989.

An investigation by newspaper Libération earlier this year described one of the merciless wars for the control of a cannabis drugs corner on the Marseille inner city estate of Micocouliers, which led to the deaths of three young men who were barely 20. Such shootings have been made easier in this Mediterranean port city by ready access to weapons from the former Yugoslavia or Africa. Speaking in December 2012 barrister Frédéric Monneret noted: “In the past there was a war between rival gangs with the aim of winning a share of the market, it obeyed a logic. The people who took part in that war did so knowing why, and what the risks were. The problem is that today, there is no longer that clarity.”

Because of the way attackers hide their faces and because of the fear of reprisals among potential witnesses, it is hard for police detectives to identity those who carry out the tit-for-tat murders. The percentage of solved cases for such killings is very low; according to Marseille police chief Jean-Paul Bonnetain talking to La Provence newspaper in March 2013, it stands at “31%”. At an ORDCS conference in June this year the inter-regional director of the French police's criminal investigation division the Police judiciaire, Christian Sainte, noted that: “An important factor is the pre-existing link that is always there between the author of the attack and the victim.” As Dominique Moyal, the public prosecutor for Aix-en-Provence in the Bouches-du-Rhône, told Libération, the role of investigators is to “understand who had been the victim of who in the past, who had already been convicted for drug dealing, who found themselves in prison with who and so on”.

But can the authorities lead the fight against a phenomenon about which so little is known? “Politicians and the French media speak every day about the tit-for-tat attacks but there is not a single piece of research on the subject,” says Thierry Colombié. “As a result everyone says anything and everything. It's very easy to state that [the killings] involve the settling of scores between small-time drugs barons on the estates. But where's the evidence?” he asks. “What about the nature of them, the motives, the victims, the attackers, the judicial proceedings of the last 40 tit-for-tat attacks in Marseille? Above all there needs to be the means put in place to allow a greater understanding, to bring an end to the myths.”

Since January 2013 Anne Kletzlen, a researcher from the ORCDS in Aix-en-Provence, has in fact been delving into the archives of the Marseille police force to draw up a profile of those involved, both victims and those suspected of being the attackers. She has gone through 112 files involving reprisal killings carried out in the Bouches-du-Rhône between April 2002 and October 2012, which involved 172 victims, 122 of them killed. The research results, which are still provisional, show that in those cases that have been solved, half of them were linked to drugs – territorial disputes, theft of products, debt and so on. However there were a number of other causes, too, such as disputes within or between slot machine businesses, the involvement of Mediterranean-wide gangs, disputes over property and even more personal issues such as questions of honour or jealousy.

Social inequality

The victims as well as the attackers involved in these incidents nearly all feature already on official police criminal files – known as Stic or the Système de Traitement des Infractions Constatées – which does not mean that their guilt was proven or even that criminal proceedings were taken against them. Their presence on the files is, however, one of the three criteria that the police rely on to record a murder as being a tit-for-tat killing between criminals. These are: the intention to kill, the way the attack is carried out, and a victim who is often “already known to the police”, as the official jargon puts it.

Since December 2012, and the arrival of 235 additional police and gendarmes, the authorities in Marseille have been engaged in an ambitious plan to “take back the housing estates”. The declared objective is not so much to eradicate drug dealing as to reduce the fear of local residents and make life hard for drugs dealers by harassing them. However, the impact of this kind of operation on tit-for-tat killings themselves is far from certain. “The person in charge of the dealing is at the head of a business: he has costs, he pays people to transport the drugs in fast cars, he pays for the drugs on credit and so on,” police superintendent Fabrice Gardon, an adviser to the chief of police in Marseille, told Mediapart in March this year. “So when we close down a dealing area we obviously create tensions in the heart of the network. But being a drug dealer is a risky profession...”

Most important of all, however, is the fact that such police operations leave intact Marseille's fundamental problems which are spread between estates in the north and south of the city. These are very poorly served by the authorities, lack council facilities and are where the majority of Marseille's social housing is concentrated. In fact Marseille suffers from greater inequality than any other city in France: in 2007 the wealthiest 10% of people in Marseille declared earnings 14.3 times greater than the poorest 10%. At that same time around 44% of children there were living below the poverty line.

Yet despite these problems, the security aspect of the much-vaunted “global approach” to the city is far more visible than those to do with education, health, jobs, housing and social issues that are supposed to accompany the police action. “There isn't the same mobilisation, everything needs to be set in motion to fight against this social insecurity that helps breed crime,” Garo Hovsépian, the socialist mayor of Marseille's 13th and 14th arrondissements, said in August this year, during yet another of interior minister Manuel Valls's visits to the city.

In December 2012, meanwhile, a former family judge and examining magistrate in Marseille, André Fortin, spelled out the limitations of the judicial and criminal system. “If the police and the legal system have an impact on the development of crime, it is relatively weak, we mustn't pretend otherwise,” said Fortin. “Instead we have to work to re-establish links with society, work again on education, the welfare of families, and I'm sorry – it's the more complicated approach.”

------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter