The Senate, France's upper parliamentary chamber, has recently put online a list of its members' outside interests. The aim is to provide transparency and reduce the risk of a conflict of interest when senators are involved in legislating on subjects they have a personal or financial stake in.

So we learn, for example, that Roger Karoutchi, senator for the Hauts-de-Seine department west of Paris, is also “an advisor on a potential television series” and that René Vestri, senator for the Alpes-Maritimes in the south-east of France, owns shares in a private beach at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, an exclusive resort on the Côte d'Azur. The register of members' interests also reveals that André Gattolin, a former director of marketing for the daily newspaper Libération and another senator for the Hauts-de-Seine, is a “consultant in journalistic services” and that Ronan Dantec, a senator for the Loire-Atlantique in the west of France, is an “author of illustrated history books”.

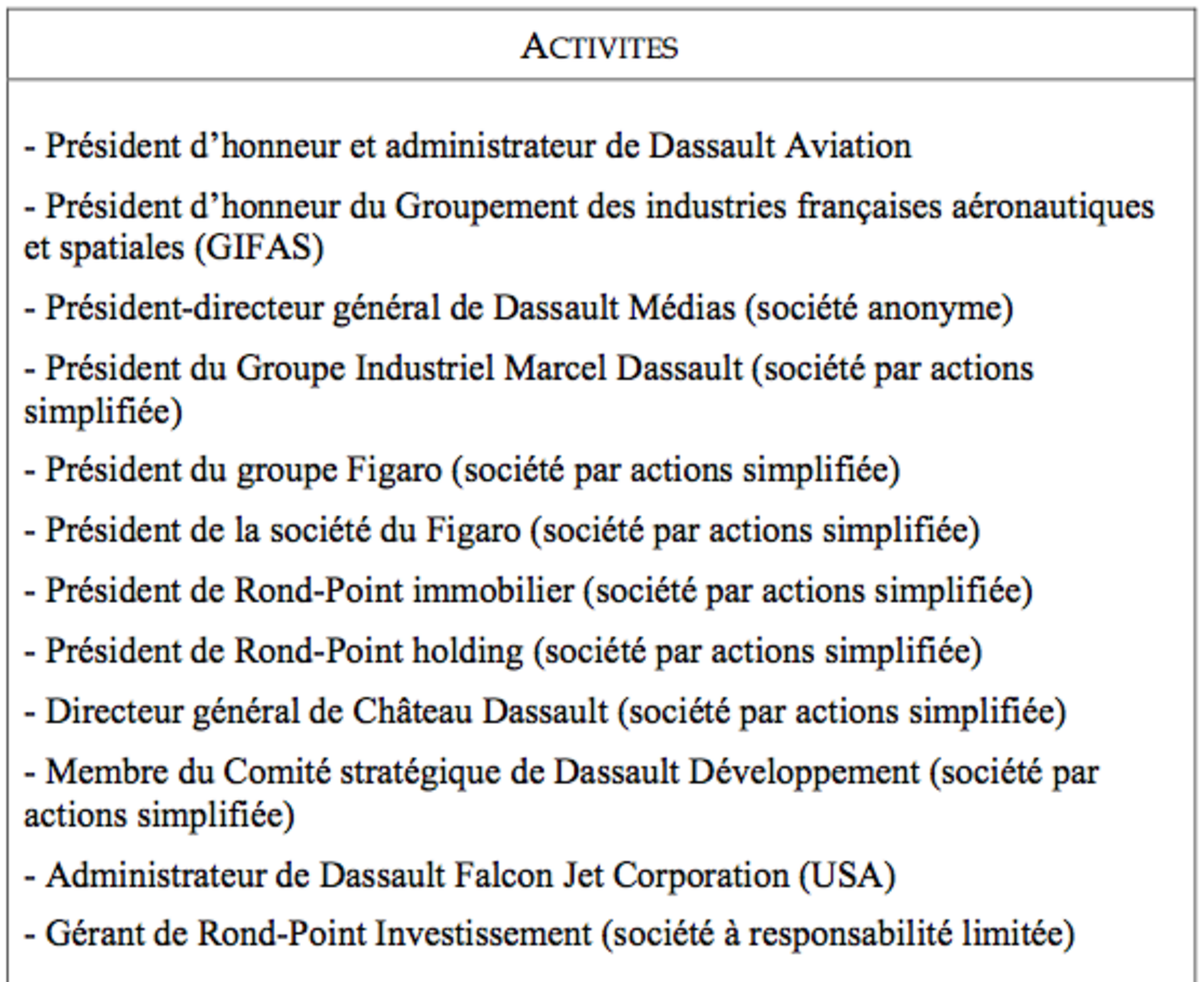

It's far from clear that these particular details will make a major contribution to preventing conflicts of interest among senators. But for those elected representatives with many and extensive outside activities such as billionaire businessman Serge Dassault, senator for the Essonne department south of Paris, and financial expert Philippe Marini, who is president of the Senate’s finance committee and a senator in the Oise, north of Paris, the exercise does represent more of an inconvenience. The listing of their many different positions in private companies in this way inevitably raises questions.

Below in French is the declaration of interests from Serge Dassault:

This is the declaration by Philippe Marini::

In particular the online declaration of members' interests will be hard for a series of elected politicians - largely unknown to the general public – who have until now lived a hidden double or even triple life sheltered from media scrutiny.

The 348 senators were asked by the new Left majority in the Senate - brought about by last September’s Senate elections - to produce a declaration that listed in one section their “professional or general interest activities, even if not paid”, and in another their “financial involvement” in businesses. This means shares and securities above a value of 15,000 euros. The aim is that this transparency will not just make journalists and the public take note of their activities, but also fellow parliamentarians too.

Up until now only government ministers have been subject to a similar procedure, as Members of Parliament - députés – have preferred to make their declarations of interests just to an internal ethics commissioner, and no one else.

Within ten days of the list going online just a couple of senators had still not completed their declaration. Many of the senators – doubtless a majority – have simply replied “Nil” to the question about their other financial interests. As for example the former sports minister and current Paris senator Chantal Jouanno.

The Senate has not, it is true, put in place any sanction for those members who might “omit” to reveal their private interests. In the same way the authorities ask for no information on the payments themselves. So, for example, it is impossible to know what salary Pierre Charon – the former advisor and confident to Nicolas Sarkozy and now a senator for Paris – pays himself as head of Janus Consultant, his communications consultancy business.

In the end one imagines that a number of senators - whose CVs have not been examined by journalists up to now – will merit being placed under greater scrutiny each time Parliament legislates on their sector of activity. For example Daniel Laurent, senator for the Charente-Maritime in the west of France who is chief executive of a transport company, Transpost Océan, which turned over 3.7 million euros in 2010; François Zochetto, senator for the Mayenne in north-west France and shareholder in a group – Grevet Prévosto – specialising in restoring old buildings; Alain Chatillon, senator for the Haute-Garonne in south-west France and boss of Ramses, a holding company with a stake in a cosmetics laboratory, Biocos Marketing Développement, and a pharmaceutical laboratory, Top Pharm; Ambroise Dupont, senator for Calvados in north-west France, horse breeder and a member of several racing businesses; Marcel Deneux, a senator for the Somme in northern France, who is “vice-president of Alliance, an agri-food company”.

'It's a delicate subject'

With diligent searching, some of these facts were already accessible, but not all in one place. Other details had until now been reserved solely for bankers (such as the Crédit coopératif bonds owned by Michel Delebarre, senator for the Nord department in the north of France, or the portfolio of shares in Air France, telecommunications firm Bouygues, electricity firm EDF, France Telecom, oil company Total and media firm Vivendi owned by Gérard Cornu, senator for the Eure-et-Loir department south-west of Paris).

All are now set out on the Senate’s website, just a mouse click away from the public – even if they have to use a microscope to read the link on the home page (see below). However, there are no rules in place to exclude a senator from debates in case of a conflict arising on a piece of legislation.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“Here everyone is felt to be honest. We therefore didn't set out with the idea that it was about hunting dishonest people,” says socialist senator Alain Anziani, one of the Senate's three Quaestors who look after financial affairs concerning members. “We looked at transparency as a means of providing information regarding certain members, a means of making people aware. In the future senators might consider that such and such a colleague, in view of their declaration of interests, is not the best placed to look after such and such a legislative proposal, to carry out investigations or to lay down amendments and so on.” In other words no compulsion, instead a hope that self-regulation will work.

More daring measures, recommended in 2010 by a cross-party group of members including Alain Anziani, were therefore rejected. In particular they discarded the idea of putting a cap on the additional earnings a senator could make, as in the United States. “We have taken a different approach,” admits Anziani. “Senators have been left their freedom, but also given their responsibilities in relation to public opinion.”

“It's progress,” insists Catherine Tasca, a former minister of culture and president of the Senate's Ethics Committee, a body to which the president of the Senate or the Senate office could refer the most extreme cases for them to give a formal recommendation.

Tasca is cautious about the issue of conflict of interest. “It's a delicate subject, you can't restrict someone elected by the people from taking part in a debate. That said, perhaps certain new incompatibilities should be enshrined in law, to ban a citizen exercising such and such a profession from standing for election. Doubtless there's a debate to be had on that...”

President François Hollande, questioned during the election campaign in April on France 2 television about improving standards in political life, showed a strong desire to legislate against conflicts of interest. “There will be an ethics charter,” he said. “You cannot have another job when you are a member of the government. That will also be the same for Parliament.”

According to Hollande's adviser on judicial and legal matters at the time, André Vallini, the then presidential candidate had got a little carried away on the issue. But it was at least envisaged banning elected members from also being a commercial lawyer or being part of a company's supervisory board. The Senate’s initiative in putting online all the senators' outside interests shows the scale of the problem.

---------------------------------

English version: Michael Streeter