A strange spiny plant sits on a cupboard in the office of Alain Winter, deputy director of security for the Bas-Rhin département – roughly equivalent to a county – in north-east France and one of the country's architects of situational crime prevention. "It's an anti-intrusion plant, it's even used by car dealers to dissuade burglars," he explains.

Winter should know about such things. From 2007 to 2011 he was adviser to Frédéric Péchenard, former director of the French national police service under President Nicolas Sarkozy. His mission was to implement situational crime prevention, a concept that had been imported in the 1990s from Britain but which had been given short shrift in France until then.

The theory of situational crime prevention emerged in the 1940s and was developed in the 1980s, chiefly by criminologist Ronald Clarke, who was then working for the Home Office in Britain. It was Clarke who first coined the term to describe his idea that criminals are rational beings who seek to limit their risks and maximise their advantages.

"The physical and social environment of society creates occasions for crime by bringing together, in time and space, three basic components: a probable criminal; an appropriate target; and the absence of sufficient dissuasion," he wrote. Prevention, therefore, involves making it harder and more dangerous to commit a crime.

The idea does not have universal support, however. French geographer Bilel Benbouzid, who wrote his doctoral thesis on the application of Clarke's theory, explains that situational crime prevention turns much accepted ideology on its head, since it is more concerned with the committing of a crime than in the social conditions under which criminality appears. "It is no longer about improving society to the point where social justice is such that crime will have disappeared, but about preventing victimisation by physical dissuasion, by forging a living environment that is not conducive to criminal acts," he wrote.

The concept made its debut on the French statute books in 1995 in a law brought in by then interior minister Charles Pasqua, which made it compulsory for housing developers and contractors to take security considerations into account in their plans. Wider acceptance of the idea was expounded in a 2002 law outlining policy directions for internal security, known as Lopsi 1.

That legal text accepted the precepts of situational crime prevention, stating: "It is indeed now understood that certain types of urban environment or economic activity can be conducive to criminality, and that it is possible to prevent this or to reduce sources of insecurity through architecture and town planning." But there was huge resistance at the transport and public works ministries - responsible for transport planning and infrastructure and now part of the Ministry for the Environment, Sustainable Development and Energy - and the law was not signed into application until 2007 as part of a response to a spate of urban riots in 2005.

Then in March 2011 came a decree under which police provide input for urban planning projects in deprived areas, and contractors are obliged to commission studies of public safety and security before embarking on any urban renovation project involving the demolition of more than 500 homes. Such studies are to be carried out by private consultants and provide a snapshot of criminal activity in the area in question and pinpoint any security loopholes in an urban project.

Police input into urban management is a good thing, according to Commissioner Stéphanie Boisnard, head of the crime prevention department at the Interior Ministry. "They know how the criminals operate and about the public nuisances and disputes over land use in a given area," she said.

But Winter says that, overall, there has been a missed opportunity. The French national urban renovation agency ANRU began a major urban renewal programme in 2003, and this is now drawing to a close. Very few security studies were actually carried out for that programme. "The laws came too late," Winter said. "We are at the end of the ANRU programme so it is very difficult, we're only intervening at the margins."

Besides resistance at the old public works ministry, Winter also blames reticence on the part of some architects who are already fed up with the plethora of constraints imposed on them by fire regulations. "So they are mistrustful as soon as they see you," he said.

There are other reasons the concept of situational crime prevention has been resisted, according to architect Paul Landauer. "There has been quite strong pressure from the government, and a certain resistance by professionals in urban renovation because behind it all, there seemed to be mostly the idea of installing video surveillance in difficult neighbourhoods," he said. There were also plans to cut down trees to create greater visibility, he added.

Better street lighting and anti-riot designs

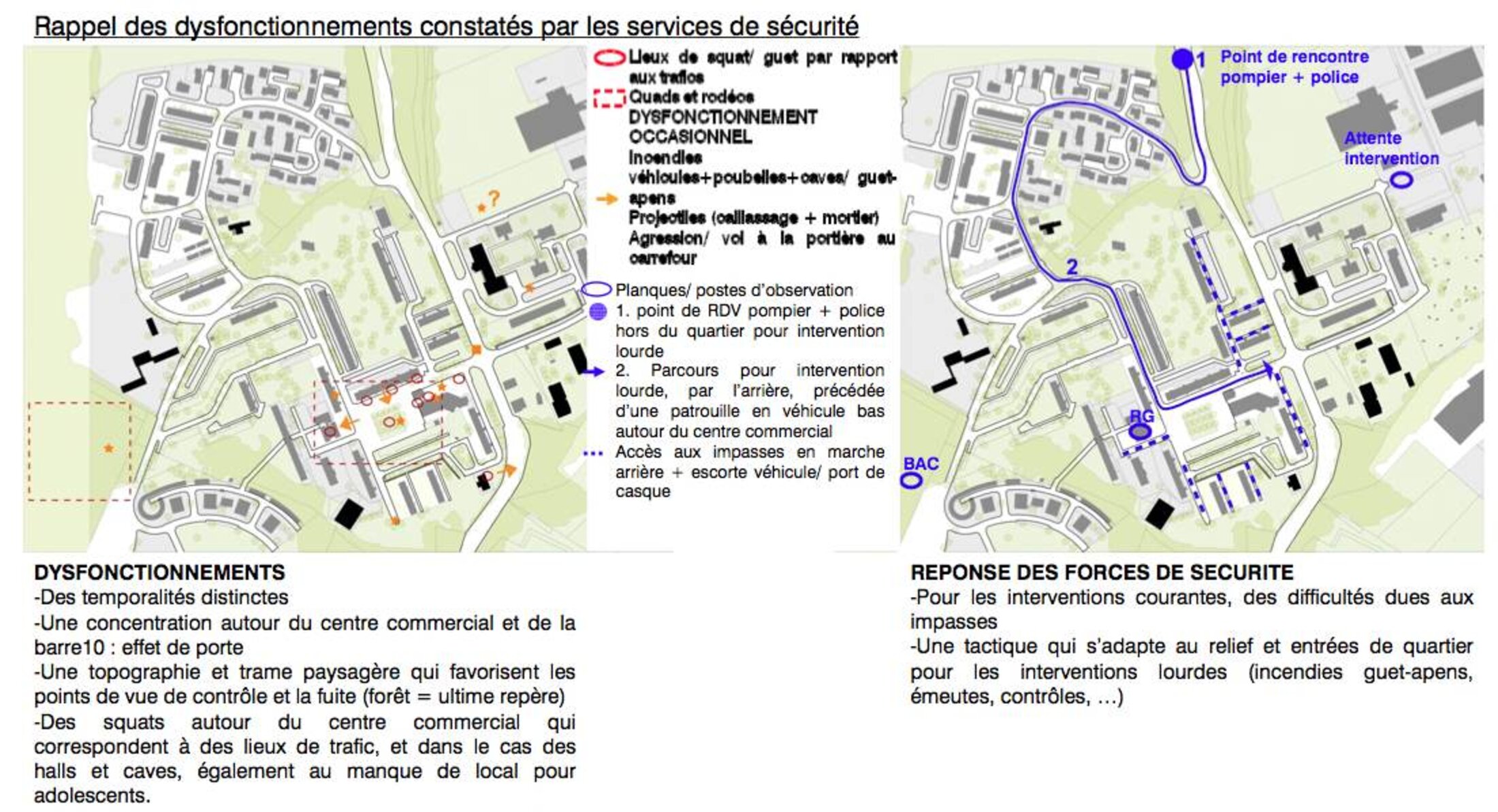

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Despite reluctance in some quarters, several cities, including Paris, Lyon and Strasbourg, have already begun to implement situational crime prevention in a bid to avoid repeating the urban planning errors of the 1960s and 1970s. Instead, plans for housing developments now include entrances for law enforcement agencies, avoid dead-ends that can be used for ambushes and do away with central walkways and flat roofs and overhead footbridges from which rioters can throw projectiles.

In addition street lighting is improved, recesses that were so conducive to muggings are no longer built, the bottom floor of buildings is now used for residential occupation, and access to buildings is controlled by digital door codes to avoid common areas being used as places for groups to gather.

"Security isn't the main aim but it is part of the overall job," said Marie Courouble, head of social policy at ANRU. "When we do urban renovation, we put in lighting, we make it easier to understand space by differentiating public and private spaces, and we make things accessible, which the drug dealers don’t like."

Strasbourg is a case in point. Francis Jaecki, the city's deputy director for security and prevention, took up his job in 2001 after a 30-year career in the police. He has had a hard time convincing urban planners of the importance of security considerations in design. "No one argues any more about fire safety measures or norms for the disabled, but it is more difficult to be heard on questions of security," he said.

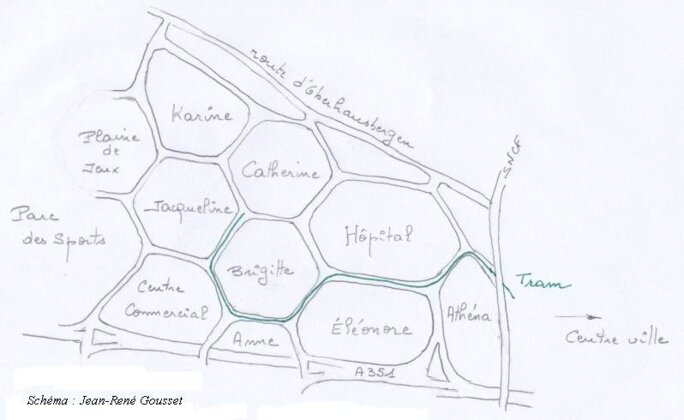

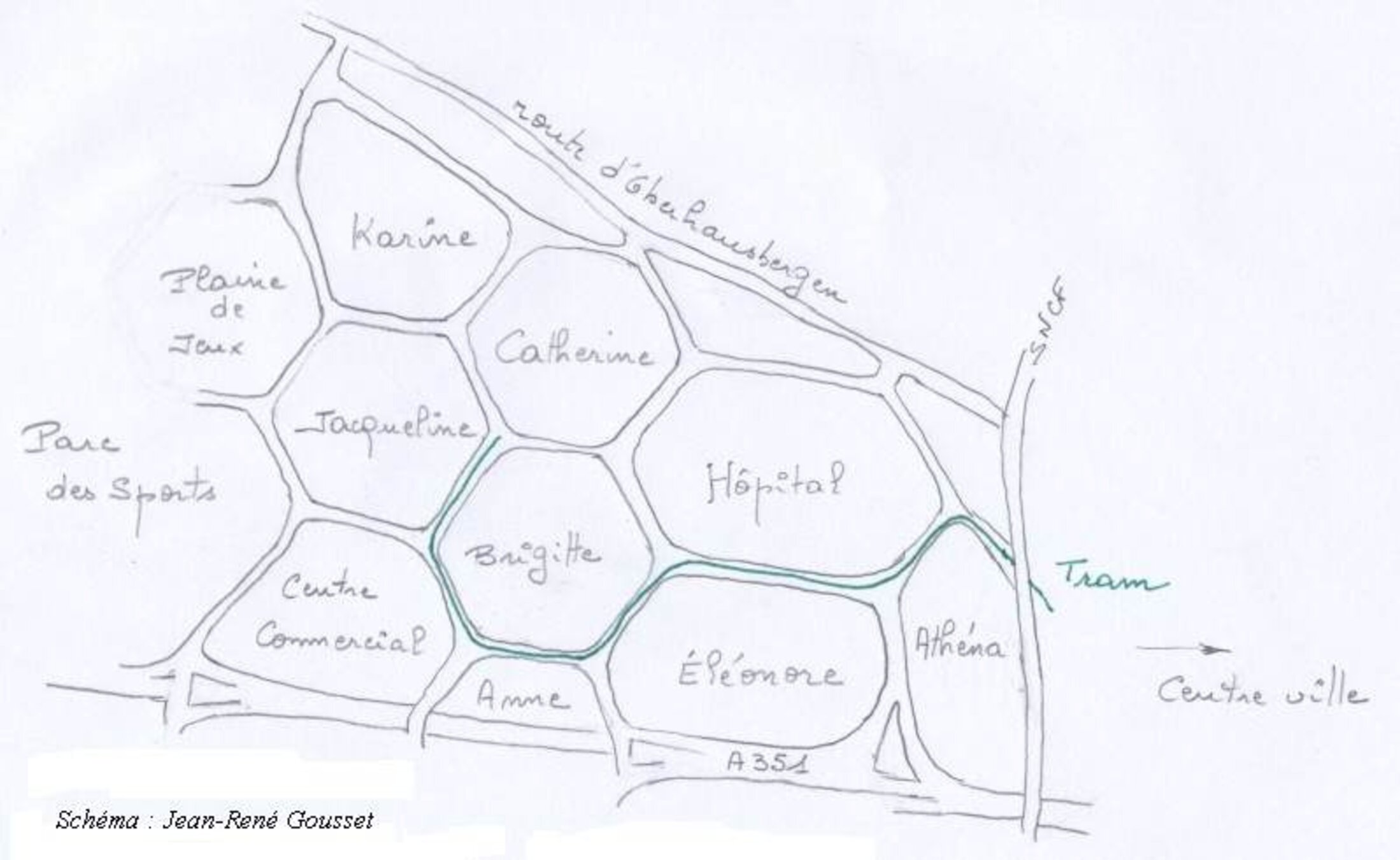

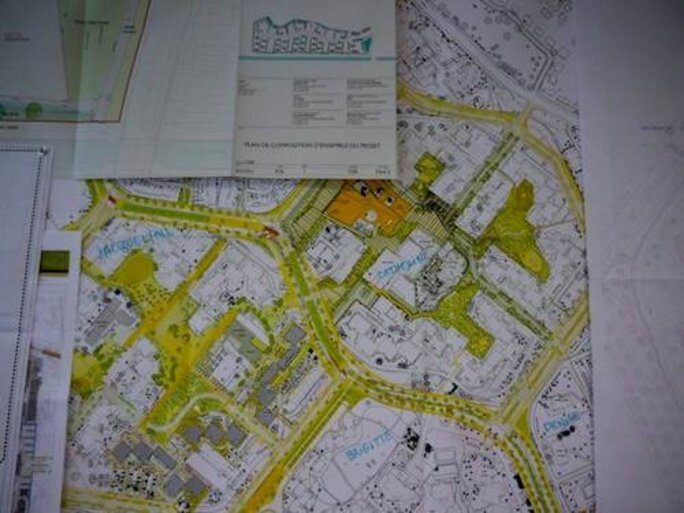

Enlargement : Illustration 4

One of three Strasbourg sink estates now undergoing a facelift, Hautepierre, was built in the early 1970s on a hexagonal grid, with residences and pedestrian areas bounded by roads with angles of 120° so that cars could drive through at a constant 60 km/hour (about 37 miles per hour). The only side roads were dead-ends provided for parking.

Police were involved at Hautepierre from the start. "One of their requests was to abolish all the dead-end side roads which allowed the people the police wanted to stop to find ways to get away," said Lucie Moreau, the project head for city hall.

"For certain inhabitants of the neighbourhood, that is a way to bring in control by authority, as police cars could patrol on the inside," commented architect and urban planner Volker Ziegler on a blog run by CUEJ, the Strasbourg journalism school.

There has also been agreement between the various agencies involved to enclose most of the poorly-lit porch areas underneath buildings and to demolish and rebuild a youth club which was badly located and conducive to drug dealing. "It was an extension of a block of flats with a flat roof from which you could observe everything that was going on and throw projectiles onto emergency workers," Moreau said.

The aim in all this is not to build bunkers, she said. "Planting a tree at a strategic place can also allow us to solve problems, for example opposite shops to block any attempt to ram the windows." However, she did not hide what had motivated such policies. "There is nevertheless a fairly clear link between the urban riots and the urban renovation decided upon since."

Security considerations for hedges, trees and even benches

Hundreds of Strasbourg police officers have been trained in situational crime prevention techniques and each department has at least one police officer or gendarme designated as a safety reference officer. Winter set up the training scheme, but in the Bas-Rhin departement only three police officers and two gendarmes have become specialist situational crime prevention officers since 2011.

"Unlike fire safety, there are no norms," Winter says. "We have an educational role. We make contractors think about building security. Construction of buildings is not a neutral act in certain sensitive neighbourhoods. You need to know what risks they are exposed to, who will guarantee surveillance, ask the right questions."

The walls of the bureau in Strasbourg’s central police station from which the the specialist crime prevention officers work are covered in maps, like one for a new environmentally-friendly housing development at Illkirch next to the Rhine-Rhone canal. Even eco-constructions are supposed to avoid flat roofs, a particular hobby horse for the specialist officers. They also dole out common-sense advice, like locating letter boxes in thoroughfares to avoid vandalism, not placing play areas right under windows to avoid noise, and planning to have on-site caretakers.

They also advise that trees should be pruned to a maximum height of two or three metres so as not to obstruct cameras, and hedges kept to a height that allows people to see over them. Digging a ditch would prevent Roma or other travellers from parking their caravans on the green spaces in the eco-construction area, they point out.

There are even security issues involved in the choice of building materials. For the redevelopment of the working class Port du Rhin neighbourhood, the crime prevention officers recommended that public facilities be made of mineral substances "to avoid benches being burned". One officer explained that even surface material matters – adding different levels to stop motorbike riders doing "wheelies", or avoiding paving stones that can be dug up “and used as projectiles”. Hedges, again, are important, as if they are too high “they encourage a feeling of anxiety”. The officer notes: “You should be able to see everything at a glance.”

These details can sometimes make a big difference. "For example, we have standardized the windows on all the entrances to CUS Habitat [editor’s note: city-managed housing] blocks of flats, which allows us to replace them much more quickly if they are broken and avoid one damage leading to another," said Moreau, the project head at Hautepierre.

New mosque gets advice on anti-graffiti, anti-terrorist measures

Back at Hautepierre, work has just begun on building a mosque, and the concerns are rather different. Two police officers looking after this project explained the particular problem of having secure parking for this type of building, with a square in front that is open, in a populous district known for urban violence. They had to identify from the outset whether the people using the site will come from Hautepierre itself or outside the neighbourhood, they said.

They advise making the building as linear as possible to limit "the risk of the entrance being used by peddlers and marginals", using an anti-graffiti surface to avoid damage, setting up a security service for Friday prayers to avoid troubling public order, and a system of video surveillance for the prayer hall and around the mosque "to prevent terrorist risks".

Having been slightly concerned at the beginning, the mosque's architect Pierre Bohrer says that in the end the police's role "did not ultimately have great consequences architecturally. Their recommendations were essentially common sense,” he said. “When you build a building for the public in a sensitive area such as Hautepierre or anywhere else in France you naturally take precautions!”

The specialist crime prevention officers also sit on the departmental committees overseeing video surveillance cameras, their roles being to give advice on the installation of new cameras and to evaluate the working of existing ones. They also advise individual home-owners and businesses, but here their advice is simply verbal, not written. “We don't want to create unfair competition for private service providers,” says Alain Winter.

The development of situational crime prevention has created a real market in France, with the sector shared between a dozen or so small private security practices, mostly run by former police officers. In the Strasbourg urban conglomeration alone, 15 situational crime studies have been produced since June 2011. “And we're just in the first few years of its operation,” says Francis Jaecki.

Many of these private practices certainly seem adept at processing existing information. “The private security practices rush into these security reports that are sometimes prohibitively expensive while some reports are of highly debatable quality, containing lots of cutting and pasting from one website to another,” says Alain Winter.

The real impact of situational crime prevention on crime is by its nature difficult to quantify, because of a lack of proper indicators and especially of objective analysis. In an internal report dated September 13th 2010 ANRU wrote of a 40% “reduction in crime incidents”. In some cases after renovation projects, the report noted, the “reduction had sometimes been greater”. However the same report accepts that the evaluation is still in its early stages.

According to one of the situational crime prevention police officers in Strasbourg the results of the work “will be seen over the scale of several years”. He adds: “For the time being we can simply accept that the buildings constructed in the 1970s didn't work.”

-----------------------------------

English version: Sue Landau