For more than a month, one of the largest nuclear power plants in France, situated at Paluel, close to the English Channel in Normandy, has been plagued by a series of disturbing incidents involving recurrent leaks, including that of radioactive gases, and the contamination of staff. Mediapart has obtained exclusive access to documents and witness accounts that testify to an atmosphere of fear among workers at the plant, lying 60 miles from the English coastline and which produces 7% of all French electricity output. This investigation by Jade Lindgaard and Michel de Pracontal.

-------------------------

The Paluel nuclear power plant, run by utilities giant EDF, employs 1,250 people and is composed of four, 1300 megawatt (MW) nuclear reactors. It is one of the three biggest nuclear plants in France, which counts 20 in all, along with those of Gravelines, further east along the channel coast, and Cattenom, situated close to the borders with Germany and Luxembourg.

After it entered service progressively between December 1985 and June 1986, it developed no notable problem during its first 20 years of operations. However, a series of different technical problems have latterly plagued its Number 3 reactor, which one of our sources, whose identity we have chosen to withhold as with other sources cited here, describes as the "most rotten part of the site". These include an oil leak onto a generator, a water leak of a primary circuit, a leak of radioactive gas in the reactor containment building and a leak from one or several fuel rod casings.

The management of the plant does not deny the incidents, which have remained undisclosed until now. However, there are quite conflicting appreciations of the gravity of the events among the different sources contacted for this article.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

One of them said a building close to the reactor containment block had to be evacuated on several occasions after an alarm sounded the warning that dangerous gases had been detected. The source said that, during the incident, staff "forced open the cases containing iodide tablets" to protect themselves against the threat of contamination. That incident illustrates the level of stress which affects employees despite their training for working in the very particular environment of a nuclear plant. Another source told us that fear of contamination was heightened by the fact that "the alarm goes off all the time", a problem reportedly resolved by re-setting the alarm so that it would require a greater level of gases in the air before it sounded the danger present.

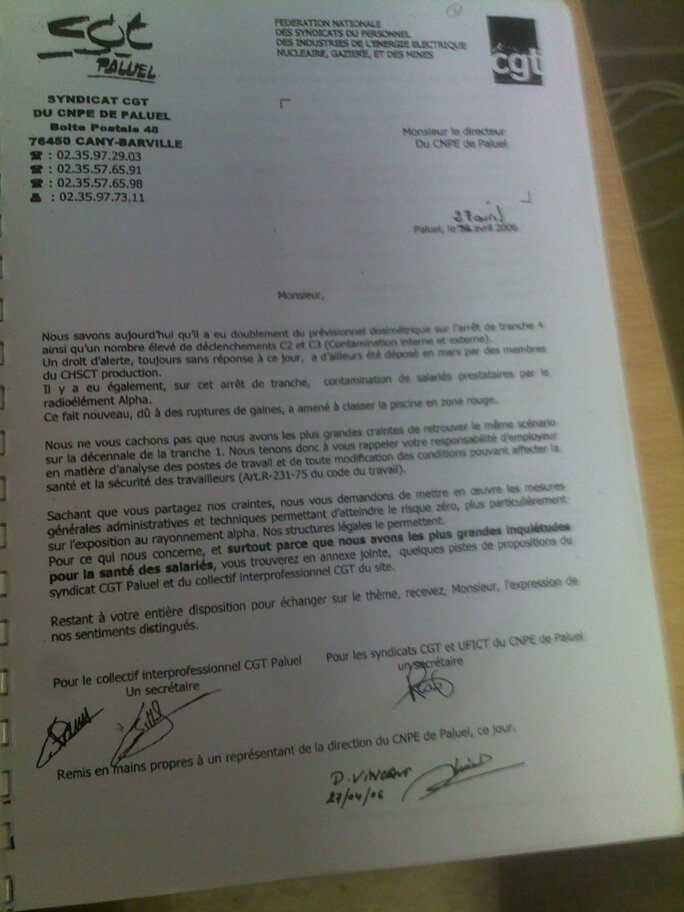

The problem is such that the local Dieppe branch of France's largest trades unions, the CGT, issued a communiqué on its website entitled ‘The Paluel plant: is EDF on the path of Tepco?' - a reference to the operators of the disaster-hit Fukushima plant in Japan.

To remedy some of the leaks, Paluel's Number 3 reactor was placed into reduced service during the public holiday weekend over June 11th - 13th, effectively a state of ticking over as opposed to being closed down, to allow repair work. During the operation, a total of 16 people who had all volunteered for the job, made up of EDF staff and sub-contractors, accidentally inhaled the radioactive gas xenon. They were found to have been contaminated after traces of this rare gas were discovered to have entered their organism.

'16 people contaminated is enormous'

One of those contaminated told Mediapart that he had been working without a self-contained breathing apparatus (mask and oxygen supply) that would have isolated him from the surrounding air environment. "The reserves of the respiratory apparatus are too limited with regard to the time for the operation, it would have required us to enter and leave the building several times, which would have increased the length of the operation," he said. He asked for his name to be withheld.

The Paluel plant's communications officer, Claire Delebarre, contacted by Mediapart, dismissed the account. "They didn't carry their respiratory apparatus because they had no need of it," she said. "This was not a case of internal contamination because xenon does not fix itself in the organism, it is rejected after several breath takes, it's like a cigarette," she added. According to a CGT official at the plant who studied the incident, the levels of the contamination were "below the acceptable limits recognised by the Nuclear Safety Authority".

However, another plant employee commented: "Sixteen people contaminated is enormous." He said it was evidence of the large quantity of radioactive gas present in the room where the group was working. Indeed, one employee who was chosen for the work that weekend refused to take part after evaluating the conditions as being too dangerous.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The incident went unreported on the website of the French Nuclear Safety Authority, the ASN, and for good reason: the ASN was not informed of the events. "That's normal, it is not an incident, it is a perceived event," commented Paluel plant communications officer Claire Delebarre.

The repair work carried out on Number 3 reactor that weekend did not resolve all of the problems. While the gas leak is now stopped, the water leak from the primary circuit continues, with repairs to the problem postponed until a later date. While the alternator had already been repaired, the leak from one or several fuel rod casings also continues. To solve that problem, the reactor must be closed down to replace the faulty elements. The operation will be carried out during the next programmed shut down, due in about a year.

According to one of our sources, the most worrying problem at Paluel is precisely that of the fuel rod casings, because they constitute the first barrage to prevent radioactive material from reaching the outside environment. These long cylinders into which are packed small radioactive uranium pellets together form the heart of the reactor.

'Leaks are typical operating incidents'

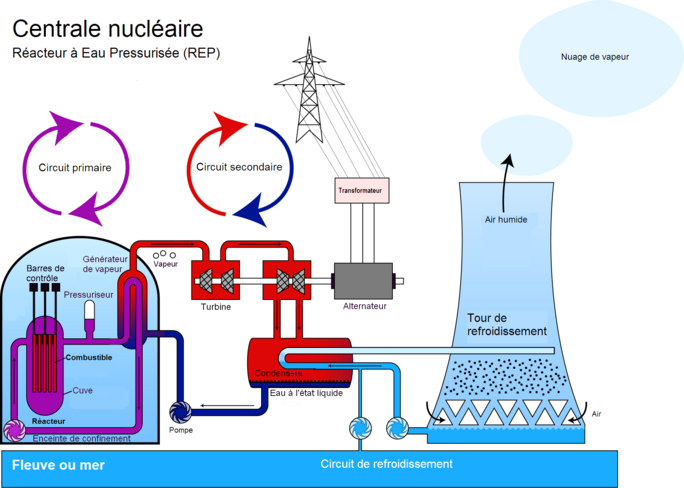

A reactor works in a similar way to a boiler. Nuclear reactions at very high temperatures take place in the radioactive fuel at its core. This heats water in the primary circuit around the reactor vessel, which in turn transfers its heat to water in the secondary circuit. This water evaporates, and the steam turns a turbine, producing electricity.

But unlike coal in a normal boiler, nuclear fuel must never enter into contact with the outside world. The safety policy the French authorities use to avoid this happening is based on a system of three barriers to enclose the radioactive fuel: the casing around the fuel rods; the reactor vessel and the primary circuit; and the outer shell of the reactor's confinement structure.

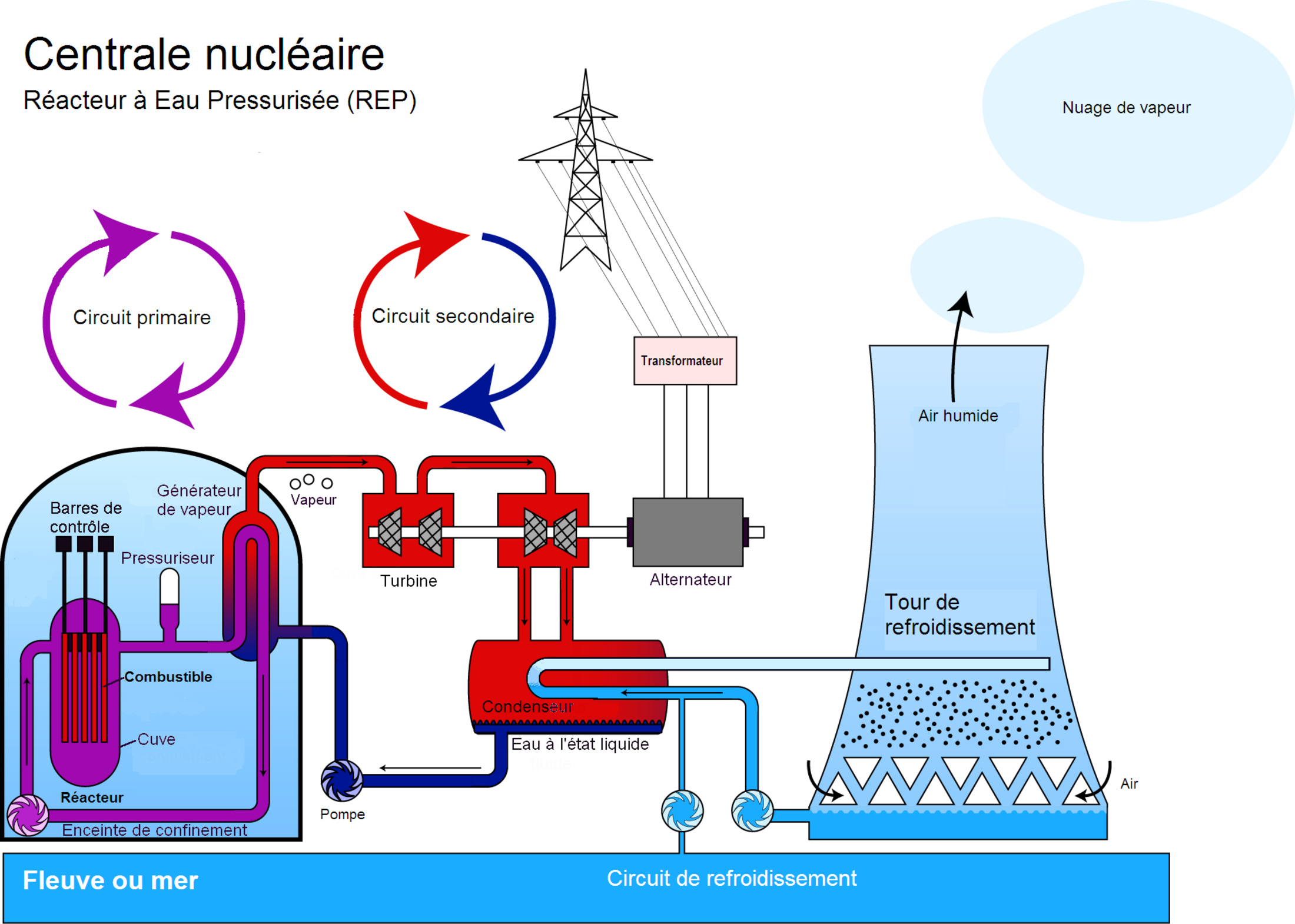

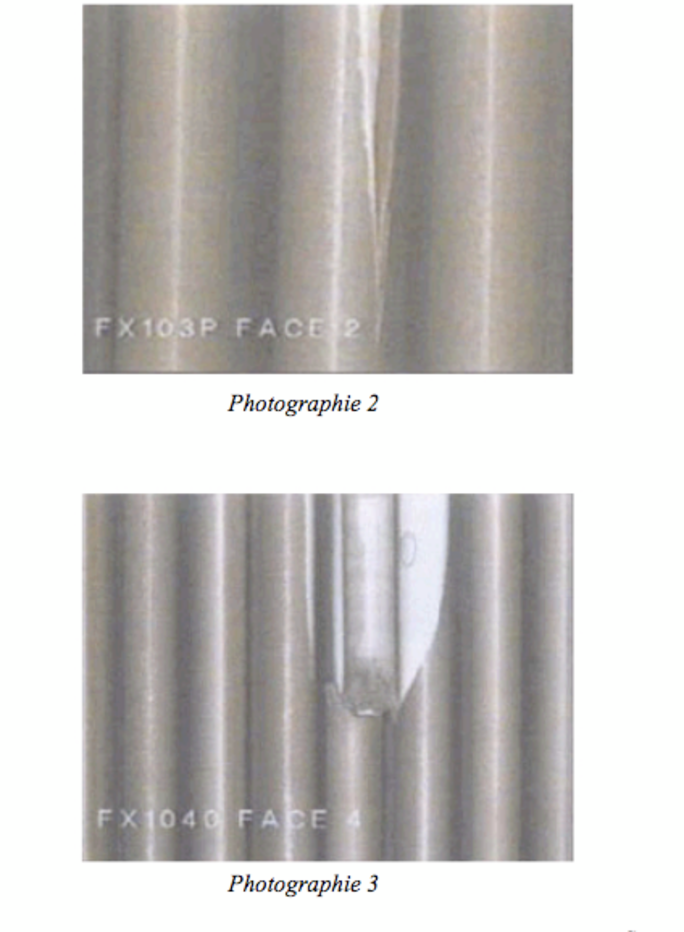

However, witnesses and documents made available to Mediapart show that at Paluel, at least one fuel rod assembly in the core of reactor Number 3 contains anything from one to several fuel rods with defective casings containing fissures. The fuel rod assemblies in question are brand new and were installed in the core the last time it was recharged in March this year. Paluel management says they were manufactured by Westinghouse.

Among the fears expressed to Mediapart about this by plant employees was the risk of wider contamination. The leaks "could lead to uncontrollable phenomena", said one employee.

For the moment, EDF has decided to keep the reactor working, possibly until the next halt for recharging fuel, which would be in around a year's time. Another source found this incomprehensible. "I can't understand why they don't decide to halt it," he said.

However, an offical with the CGT trade union at Paluel said the leaks were minimal. "They have no direct effect on the staff. They are measured, analysed, checked and controlled," he said.

Paluel communications officer Claire Delebarre said that EDF has investigated the leaks. "Our investigations show that there is a fault in the casing, but it is not a rupture, it is slightly porous and this is the case for only a single fuel assembly," she said, adding that "functioning with a minor leak is not serious in itself. It's like wine, sometimes it is corked."

The problem could extend to as many as 264 fuel rods that are contained in a single assembly. The level of radioactivity involved is estimated at 30,000 megabecquerels per tonne of water (MBq/t). Regulations dictate that once a level of 100,000 Mbq/t per day has been reached for seven consecutive days, a reactor must be halted.

It would appear that the authorities' three-barrier policy is being breached at Paluel, since in Number 3 reactor, only two of the three barriers are actually functioning. The French Nuclear Safety Authority had not replied to Mediapart's questions by the time this article was published. Delebarre claimed that leaks were not abnormal. "These are typical operating incidents," she said.

30 fuel rod casing leaks in seven years

Mediapart has compiled a history of leaks in fuel rod casings at French nuclear power plants running back 12 years.

The first incident of this kind was detected at the Cattenom power station in Lorraine, in eastern France, in October 1999. There was a high level of radioactivity in the primary circuit and the presence of xenon 133, a radioactive gas, was detected. In August 2000, measurements showed that radioactive fuel had spread into the primary circuit. In September, alpha radiation was found, suggesting a serious breach in a fuel rod casing.

And on March 15th, 2001, EDF discovered 28 fuel rod assemblies which were not leak-proof. The incident was classified as Level 1, the lowest in the 7-level international scale.

Then, in 2002, nuclear fuel rod casings at the Nogent-sur-Seine power station, near the eastern town of Troyes, were found to have deteriorated. But the reason was new; the faulty casings were made of a new zirconium alloy called M5, not the zircaloy 4 usually used for this purpose.

This M5 alloy is produced by Areva, the French state-owned nuclear plant and fuel-making giant, and was introduced by EDF to improve the efficiency of the fuel, allowing it to cut the number of times reactors have to be halted for recharging fuel.

But there was an unexpected complication. According to a study by the nuclear safety institute IRSN, M5 fuel rod casings show a failure level "four to five times above those of fuel rods in zircaloy 4 casings."

The first fuel cycle using a complete recharge with M5 casings in the Number 2 reactor at Nogent "had to be halted following contamination of the primary circuit after a record number of 39 casings ruptures in 23 assemblies," according to a report by Global Chance, an independent consultancy[Cahiers de Global Chance, n°25, September 2008].

Some 30 leaks have been detected in fuel rod casings made of the M5 alloy between 2001 and 2008, according to IRSN. In 2006, the ASN warned that "a cautious approach" should be adopted as far as M5 was concerned. EDF has since tried to improve manufacturing techniques for assemblies, but the problem has not disappeared.

In 2008, "fuel encased in M5 alloy was present in 17 of the 900 MW reactors, three of the 1300 MW reactors and the four 1450 MW reactors," IRSN said. This is equivalent to a little under half of France's installed nuclear power capacity. Since then M5 has continued to be used, notably in the new fuel rod assemblies at Paluel.

'He inhaled radioactive dust'

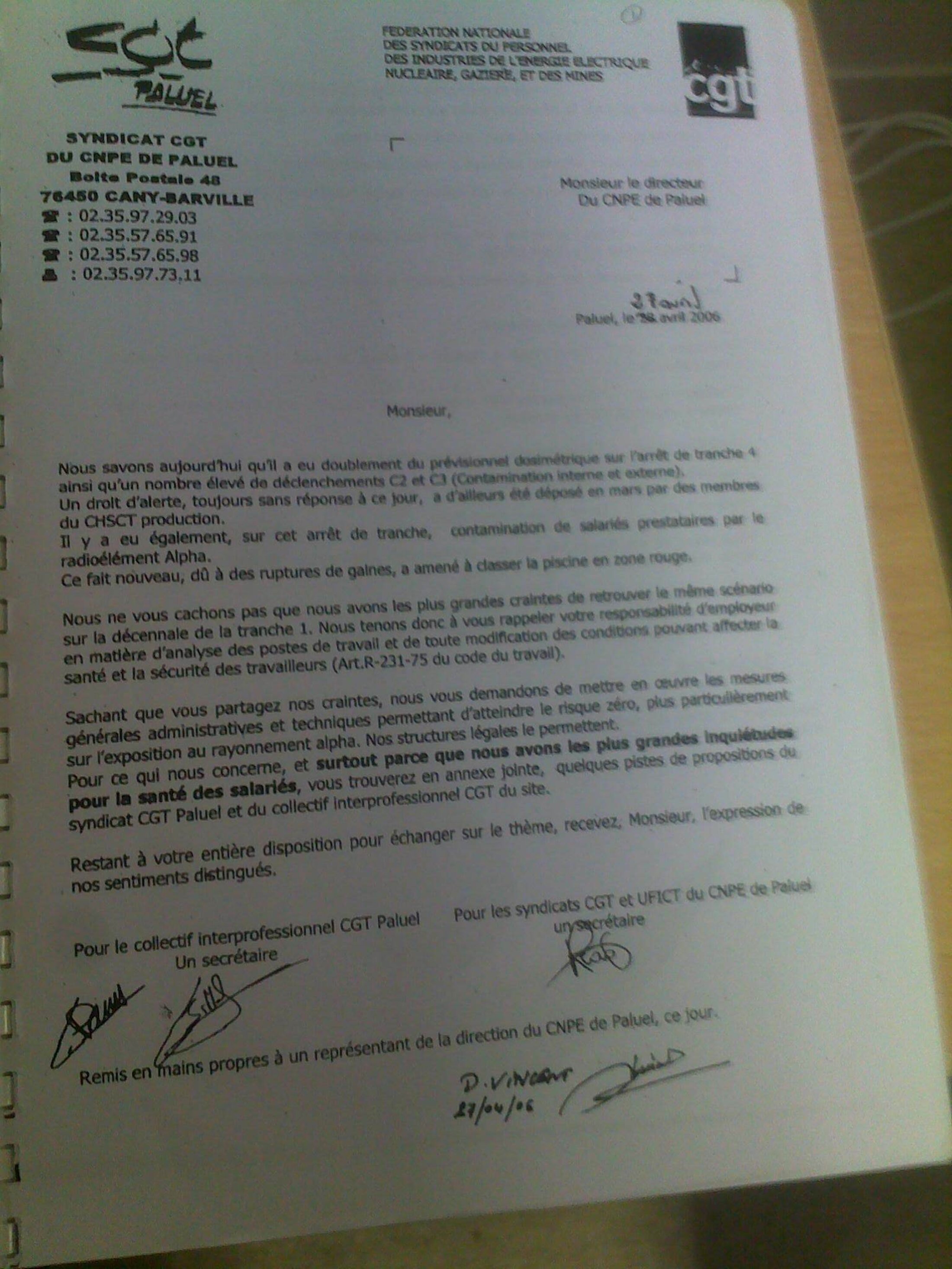

Paluel has had faulty fuel rod casings since 2006. That year, its Number 4 reactor was being prepared for a maintenance halt. Employees were warned that they could be exposed to high levels of radioactivity. "The reactor had a radioactivity index 50 times above the reactor next to it," remembers Philippe Billard, who was then a decontaminator on the site and an official of the CGT trade union.

He was worried by this and filed an alert, but was told he was exaggerating the risk. The halt went ahead. While equipment was being decontaminated, workers for Framatome, which later became Areva, were evaluating the state of the fuel using a camera. Billard saw the film from that investigation.

"I saw the fuel rod casings," he said. "The casing was open, there was a crack, and behind it there was nothing. The pellets of fuel had gone. They had gone into the primary circuit."

The reactor was halted for maintenance for 30 days. During this time some employees were exposed to half the amount of radioactivity authorised during a whole year.

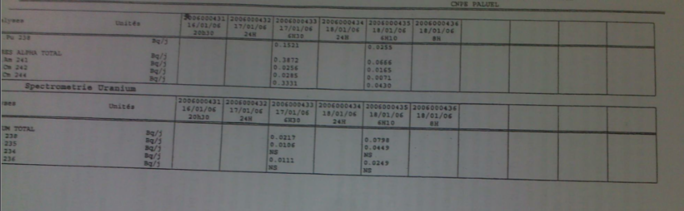

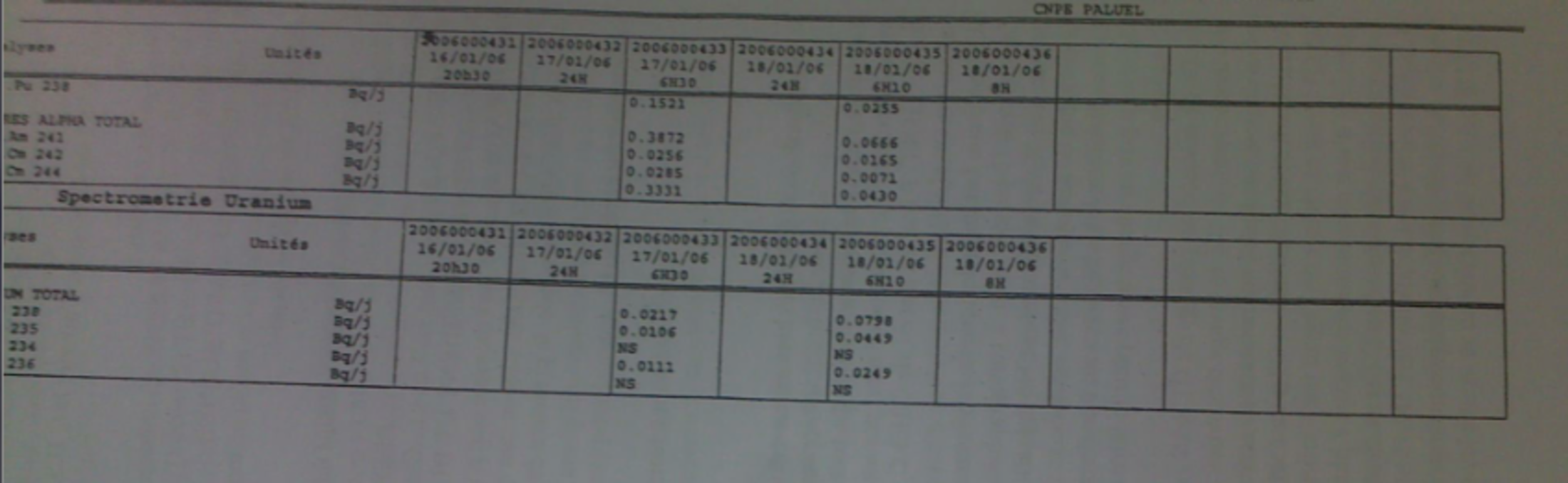

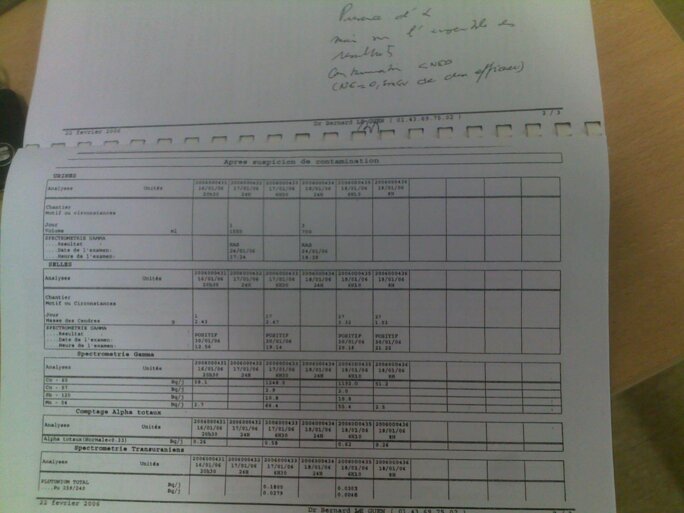

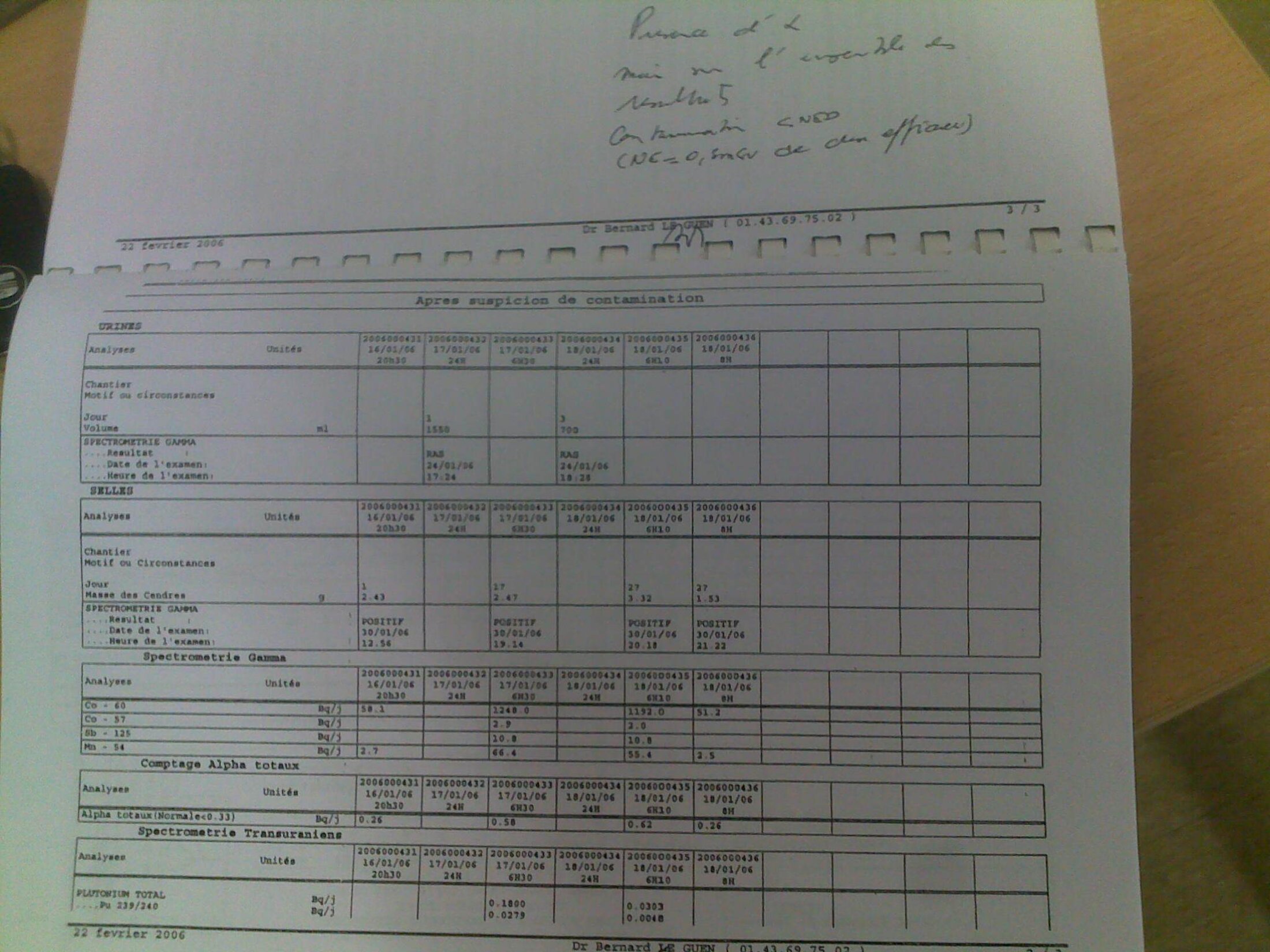

One of them, an EDF employee, sought medical examinations after the halt. The results, made available to Mediapart, showed that his body contained traces of caesium, uranium and plutonium, which are all carcinogenic beyond a certain dose.

"He had inhaled radioactive dust," Billard said. He sent a letter to Paluel management to alert them to the presence of highly dangerous alpha radiation in reactor number 4.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Such micro-doses are below the legal limit each time, but they still accumulate in the body. The EDF employee who was contaminated has since left the nuclear industry. Billard has set up an association for the health of sub-contractors, who now make up around half the nuclear industry's workforce.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

"What people are afraid of in a nuclear accident is to be contaminated and get cancer. Well, we are regularly contaminated in power stations. And we get cancer. For us, the accident has already happened. We are everyday liquidators."

People are used to hearing of liquidators at Chernobyl or Fukushima, but not in France itself. There is a perception that accidents happen to others who do not apply French safety principles, who are not lucky enough to have access to French organisation or expertise, or lack independent nuclear authorities.

But the situation at Paluel illustrates that the system is vulnerable on a day-to-day basis and functions with permanent technical and human failings. It may not be catastrophic, but nor is it reassuring. It fuels a general climate of mistrust over whether safety principles are really observed, and whether the search for productivity takes precedence over safety imperatives.

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau and Graham Tearse

(Editing by Graham Tearse)