While Socialist Party presidential candidate François Hollande won the election's first round on Sunday, it was far-right Front National party leader Marine Le Pen who came out of the contest the most jubilant.

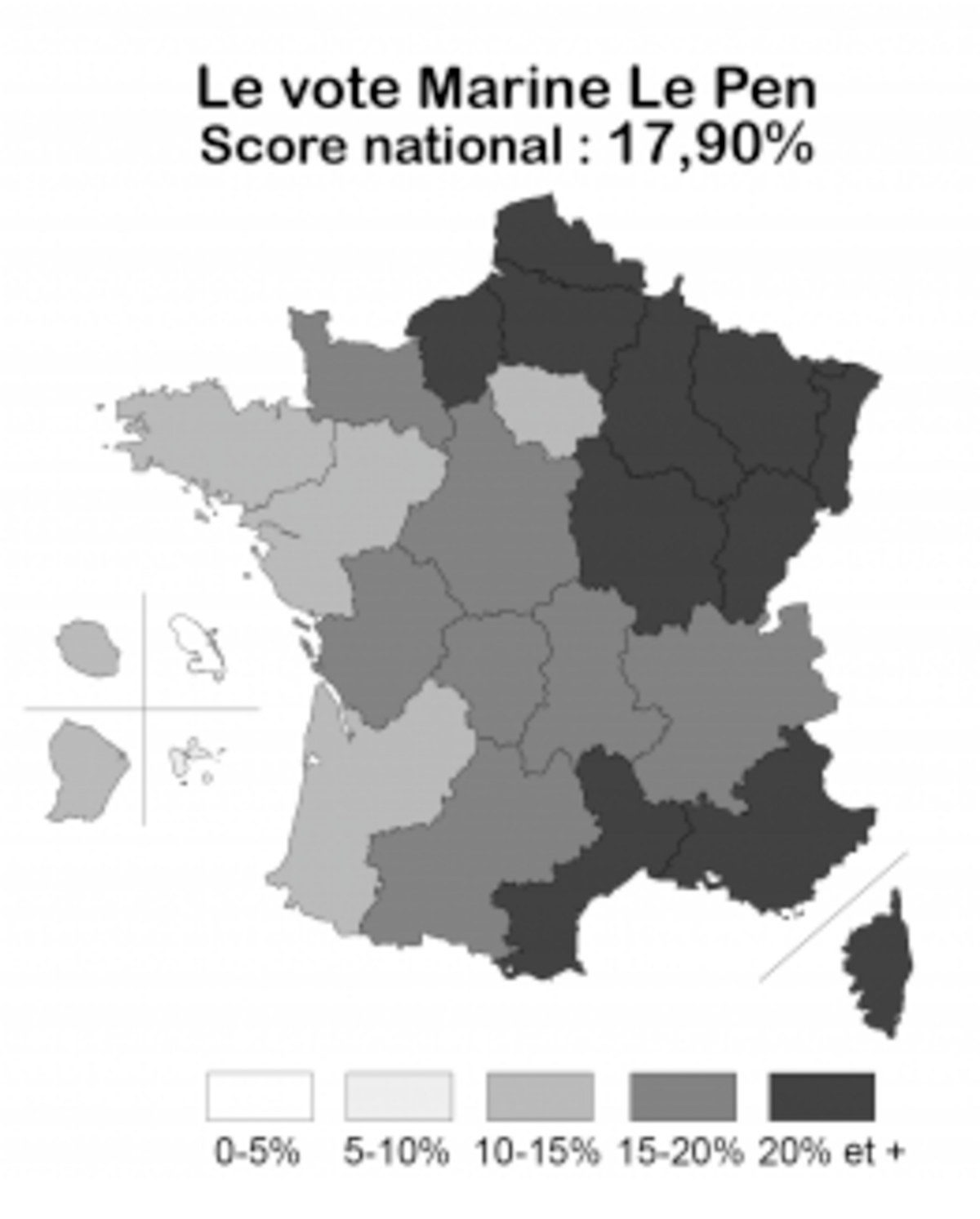

Her nationwide 17.9% slice of the vote, placing her third overall, was the highest the far-right has ever obtained in presidential elections, well beyond what opinion polls predicted, and has elevated her to the position of a broker of votes for the next round. For as Hollande and second-placed Nicolas Sarkozy are the two who now move on to the final play-off on May 6th, the outgoing president is now launched on a desperate and dismal chase for support from the far-right electorate.

Le Pen, meanwhile, is already looking forward to the June legislative elections, when she hopes her party will now consolidate its performance by winning parliamentary seats.

With her performance on Sunday, the 43 year-old, twice-divorced mother of three has finally thrown off the yoke of the legacy of her father, former parachutist Jean-Marie Le Pen, a far-right, one-eyed bogeyman figure and the party’s leader from 1972 to 2011, until now revered and missed by many within it.

But is Marine Le Pen on the threshold of transforming the Front National into a significant and popular force on the Right, or will she more likely belly-flop from the crest of a temporary wave of protest from a politically disillusioned and disenfranchised section of French society?

For an explanation of what lies behind Le Pen’s success, and where it may now lead, Mediapart turned to Sylvain Crépon, a sociology professor with Paris-Ouest-Nanterre university, a recognised specialist researcher on the Far Right, and the Front National in particular, whose recently-published book, Enquête au cœur du nouveau Front national, is an in-depth investigation into the party, its members and leaders, and its history. For Crépon, interviewed here by Michaël Hajdenberg, there was no mystery about Le Pen’s first-round triumph.

-------------------------

Mediapart: Were you surprised by Marine Le Pen’s score?

Sylvain Crépon: No, not much. I had predicted 18%. I was certain that she would be the 'third man'.

Mediapart: Why?

S.C.: Marine Le Pen stalled in the middle of her campaign, between January and March. She fell a little in the opinion polls, and that was quite logical. She had a contradictory speech, on the one hand she was playing on [political] normalization, ‘We are a party capable of governing, we are a lay, [democratic] party, and we aren’t a demonic party’. On the other hand, she was saying ‘we are an anti-system party, outside of the system’. It was somewhat inaudible. Towards the end of the campaign, she returned to fundamentals, law and order and immigration. Her father gave her a boost by making a few provocative statements, and from then on, while taking advantage of having a less demonic image than that of her father, she was able to mobilize [an electorate], certainly a tiny part of Sarkozy’s electorate, but above all those who abstain.

An IFOP opinion poll predicted an abstention rate of 29%. Of that 29%, 41% had voted for [Marine’s father and predecessor Jean-Marie] Le Pen in 2007. The Front’s electorate is sociologically very close to those who abstain. She found the way to mobilize them again.”

Mediapart: So you would argue that her victory is not down to her strategy of making the Front National appear to be a normal party, but more to the appeal of the party’s traditional refrains?

S.C.: That’s right. It’s somewhat paradoxical, but she played on both. Her image – she gained from her strategy of de-demonization and certainly picked up voters who weren’t ready to vote for her father - and the fundamentals. As long as she tried to demonstrate that she had credibility regarding economic issues, or by using the [democratic] republican visiting card, she wasn’t getting there. By returning to fundamentals, she picked up a lot of people. Which leads me to say that, beyond the protest vote, the Front National doesn’t have much room for manoeuvre. Quite simply, all the parties of protest had a weak score. The protest vote was concentrated on her.”

Mediapart: Why does she succeed now?

S.C.: The economic crisis is one explanation. But there is also the fact that the two main candidates presented a very measured line, very managerial, very technocratic, and thus difficult to understand among an electorate from a socially precarious and little-educated background. That amplified a perception of disassociation between the elites and the people, and favoured a populist discourse. There was no drive in this campaign except from among the populist leaders, [Jean-Luc] Mélenchon and Marine Le Pen, who were not from parties that proposed [policies] - managerial parties - but who were more driven, who offered horizons, a sort of enchantment which was able to attract a section of the electorate that is detaching itself from politics.

Mediapart: The question has been raised about the transfer of votes between the Far Left and the Far Right. Mélenchon scored less than predicted. Is there a link between that and Le Pen’s high score?

S.C.: No. There are no communicating doors between the two electorates, which are completely different. Sociologically, 30% of blue-collar workers vote for Marine Le Pen, while very few blue-collar workers turn towards Mélenchon. Marine Le Pen attracts those in precarious situations in the private sector, the unemployed, blue-collar workers and those without diplomas.

Mélenchon doesn’t attract those in precarious social situations, but rather those who are socially and economically integrated, lots of people from the public service payroll, those with diplomas, those disillusioned with the Socialist Party, people close to the Socialist Party, the lower middle class from the public sector payroll.

These are two populist votes, defiant towards the elites, but those with Mélenchon have a civic, [democratic] republican dimension. The people with Marine Le Pen have an ethnic dimension. These are two irreducible dimensions which very clearly distinguish each.

Mediapart: A section of the Front national’s electorate voted for Sarkozy in the 2007 presidential elections. Have they now flown back to the nest?

S.C.: It’s a bit too early to say. But one could advance such a hypothesis. One also needs to check whether the first-time voters didn’t turn in mass towards Le Pen.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Mediapart: Was Nicolas Sarkozy strategically correct to woo the Front National electorate?

S.C.: No. The results show the limit of such a campaign. But everything leads one to believe that if Sarkozy loses the election, the Right will be faced with a major dilemma. It is the failure of Nicolas Sarkozy but, at the same time, there is a front National with 20%. Should you move to the Centre? Should you move further to the Right?

Mediapart: Was the Front National score affected by the campaign themes, such as the row over how much halal-prepared meat is unknowingly consumed by the broad public?

S.C.: In my opinion, it plays a part. Among discussions I’ve held, a new member of the Front National, a former member of [Nicolas Sarkozy’s ruling] UMP party, told me, ‘Sarkozy contributed to the legitimization for me of National Front arguments.’ So I think that contributed in jumping a barrier.

Mediapart: Sarkozy’s campaign already leant steeply to the Right in 2007. Why didn’t his latest campaign have the same effect on an electorate that had turned its back the Front National?

S.C.: The president is at the end of five years in government. His result sheet no doubt counted against him, the economic crisis, unemployment. But he was also elected thanks to the blue-collar Front National voters. And his status as the president of the rich may have contributed to cutting him off from this Front National electorate, those lowly private sector employees among whom that strengthened their mistrust of elites.

Mediapart: Do you believe the Front National has now reached the limits of its electoral potential, or that rather this is the beginning of a path of progression?

S.C.: That’s difficult to answer. I think the Front National is reaching its climax, because for me it remains a protest vote, against elites. According to the surveys carried out by different institutions, the party’s electorate seldom supports the solutions put forward by the Front National. On the question of leaving the euro, for example, not even 20% of its electorate is in favour of that solution. Protest voters could abstain, but to vote Front National is to remind the political figures of one’s existence.

Symbolically, it’s an unprecedented landslide. But will it know how to capitalize on it? Will it succeed in gaining Members of Parliament [in the June legislative elections]? The Front National could obtain some, notably her [Marine Le Pen] in the Nord [northern region]. But a parliamentary group, no.

Mediapart: What might be her strategy?

S.C.: If she changes its name, she could turn the page on Jean-Marie Le Pen and the Far Right and attempt to position it as a neo-populist party, a little like the Dutch or Swiss models.

Mediapart: Will the score she achieved encourage her towards this?

S.C.: I don’t know. She won’t have her father in her way anymore, she is no longer dependent upon him. She has done better than him. That will silence all the internal dissension, [that was present] even at the very heart of her team. On an internal level now she can do what she likes, she has her hands free. She could change the name. She could also not change it. She could hold her hand out to [Sarkozy’s ruling] UMP party to cause it embarrassment. She could try to set it at loggerheads within. But the Front National is not very well equipped in terms of strategy. It’s principal Achille's heel is brainpower.

-------------------------

- Sylvain Crépon's book 'Enquête au cœur du nouveau Front national' (An investigation into the heart of the new Front National), is published by Nouveau Monde, priced 19.9 euros.

-------------------------

English version: Graham Tearse