In 2010 the former Société Générale trader Jerôme Kerviel was convicted of forgery, breach of trust and unauthorised use of computers in relation to a series of trades that cost the bank up to 4.9 billion euros in January 2008. In October 2012 the ex-trader lost an appeal against his sentence of three years in jail with two more years suspended. The appeal court also confirmed that he must pay back the losses of 4.9 billion euros to Société Générale, though the bank has said it will not enforce this.

However, the story does not end there. On 4th July Kerviel, who does not deny making highly speculative trades but says his bosses knew what he was doing, will take his former employer to an industrial tribunal claiming he was unfairly dismissed and seeking 4.9 billion euros in damages – equal to the sum he is said to have lost the bank. And his lawyer has now made a formal complaint alleging forgery and use of false documents in relation to the affair. In particular the trader’s legal team has highlighted some curious discrepancies in the tape recordings made of Kerviel's questioning by his bank superiors when his huge losses were uncovered; recordings that formed the basis of his conviction. Mediapart's Martine Orange investigates.

---------------------------------------------

Five years have passed since the Kerviel affair began, two court cases have taken place, and the matter is now before the highest French appeal court the Cour de cassation. It may, however, be some more years yet before final judgement is given by that institution on whether the trader Jérôme Kerviel was fairly convicted and sentenced over trades that cost the French bank Société Générale 4.9 billion euros.

The bank itself has quickly put the affair behind it and and moved on. Yet there are others who will not let the matter rest there. For them what happened to Kerviel is like a stone that gets stuck inside your shoe; a constant source of irritation that cannot be ignored. That is why a steady trickle of Société Générale employees past and present plus others from the world of finance continue to arrive at the offices of Kerviel's lawyer David Koubbi to recount what they saw, what they could not or did not dare to say at the time, or to speak of certain practices carried out by the bank and the world of finance in general.

“Why this email: disgust. At seeing that for the sake of image, Société Générale hounded a man, at seeing that SG could have reacted in time at that period and did nothing, for having worked like a madman after the Jérôme Kerviel fallout only to see a legal process as rubbish as that one,” writes one former auditor. He says that at the time of the Kerviel affair he was responsible for operational risk management at the bank and claims that he had alerted his superiors to the problems at 'desk delta one', where Kerviel worked, several months before the affair broke.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

For him and others who have come forward, Jérôme Kerviel's trial in 2010 was unfair, with the version of the facts recounted by the bank and accepted by the judges simply not corresponding to reality. Kerviel is certainly guilty, as he himself accepts, of having held some outrageous speculative positions - “mad” as he now says – which culminated in 50 billion euros being bet on the markets on 18th January 2008.

But for the new witnesses the story cannot simply be summed up as that of a mad trader on the one hand and a bank on the other that was merely a victim and which saw nothing. For them, it is just not plausible that the bank was completely unaware of his actions, that it saw or heard nothing during almost three years. There are too many silences, too much opacity and too little coherence in the bank's actions and defence for that.

The punishment meted out to Jérome Kerviel also seems disproportionate to many; not just the jail term but the fact that he was ordered to pay back the 4.9 billion euros in losses and interest suffered by the bank, in effect a kind of economic punishment in perpetuity. By way of comparison, when Jean-Yves Haberer and François Gille were held responsible for the failure of the state-owned bank Crédit lyonnais in 1993 – which cost taxpayers 20 billion euros – they were convicted in 2005 for giving a false picture of Crédit lyonnais's true performance and given suspended prison sentences of 18 and 9 months respectively, and ordered to pay a symbolic one euro back to the bank. It is perhaps little wonder, then, that Kerviel's legal fight continues; indeed his case at the industrial tribunal on 4th July is being backed by the co-president and founder of the radical left Parti de Gauche, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who insists that the trader is “innocent”.

Yet many would prefer the matter simply went away; for many it already has. “Who wants to speak about the Kerviel affair?” bemoans Jacques Werren, a former employee at the Marché à Terme International de France (MATIF) futures exchange and clearing house, who gave evidence at the trial in 2010. “The trial and the verdict suited everyone. Société Générale, the world of French banking, the regulatory authorities, the financial watchdogs, all of them came out of it very well. Apart from Jérôme Kerviel, of course. But he is not part of any network that counts. No one wants to reopen the case.” The bank's senior lawyer Jean Veil confirms: “It's all in the past.”

Nonetheless Kerviel's lawyer David Koubbi has decided to restart the affair. In October last year the prosecution authorities ruled that there was no case to answer in relation to allegations by Kerviel and his lawyer of forgery and the use of false documents in the affair. Now Koubbi is trying again, this time via senior examining magistrates in Paris. At the centre of his complaint are some curious discrepancies in recordings the bank made of its executives questioning Jérôme Kerviel on the weekend of 19th and 20th January 2008 when management said they discovered for the first time what had been going on.

The missing 2 hours and 44 minutes

During those crucial 48 hours some of the bank's senior executives - Luc François, in charge of the trading floor, Christophe Mianné, jointly in charge of the trading floor, Martial Rouyère, who was Jérôme Kerviel's boss, Claire Dumas, in charge of operations, Jean-Pierre Mustier, number two at the bank and head of its corporate and investment division, Salwonir Krupa, Mustier's chief of staff – took it in turns to question the trader. They asked him to describe precisely the trading positions he had taken, how he handled the markets, which intermediaries he used, whom he consulted, what he did if he made losses, what he did if he made a profit and so on. All of this was recorded by the bank's internal telecommunications system.

During Kerviel's trial these recordings were regarded as one of the key elements in the proceedings; the conversations were between professionals and they were made before the scandal broke in public, so their content was thought to be untainted by self-interest or calculation. Everyone was trying to win Kerviel's trust to be sure that they fully understood what he had done, the bank's executives said later.

The bank's number two Jean-Pierre Mustier, in particular, can he heard making some astonishing remarks (recording, below, in French):

“We've all looked at your accounts. There's 1.4 billion. We've checked, we know how to look... But behind, is there another account?...If that's true we can make it go away, you're not finished. We know how to make it go away. If you've lost, we'll manage to make it go away...If you're still lying to us, then that will be very serious. If you're telling us the truth, it's not too serious,” says Mustier.

Then a little later on in the recording (7 minutes 27 seconds) Mustier says: “Me, I'm going to say to the shareholders on Monday: I have lost one billion on subprimes [editor's note, subprime loans]. Roughly speaking, what you've gained I have lost. It's only money. It won't stop me sleeping. ...The bugger of it is that it's all happening at an awkward time. Tomorrow, there's a board [meeting]. Had this board [meeting] been in a week's time, in a fortnight, it wouldn’t have been that serious. But the board [meeting] is tomorrow. We have a board [meeting] tomorrow. A board [meeting] in a week or a fortnight...We have fewer than 24 hours to find the truth and justify the truth...”

The bank's lawyers spoke of these documents as if they constituted the trader’s confessions. A retranscription of the audio files was supplied to the judicial authorities by the bank.

On several occasions Jérôme Kerviel's lawyers asked to have access to these recordings, which had been sealed. In 2008 the examining magistrate Renaud Van Ruymbeke refused their request, explaining that “the opening of these seals, whose integrity must be preserved, cannot be ordered as a matter of course”. When the lawyers tried again in 2009 to get their hands on the recordings they were told: “The request for copies of the sealed [recordings] seems to serve no purpose, their retranscription figuring in the proceedings.”

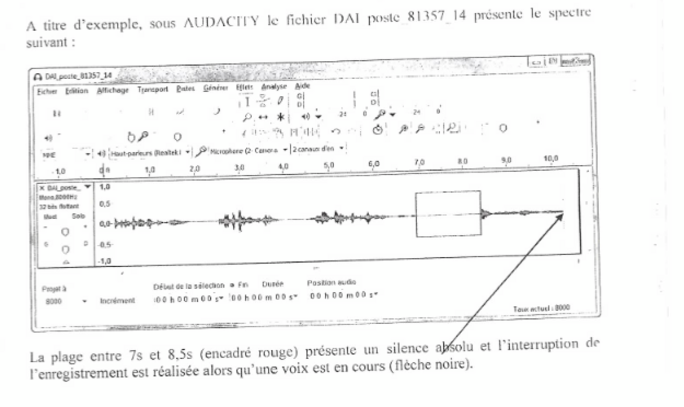

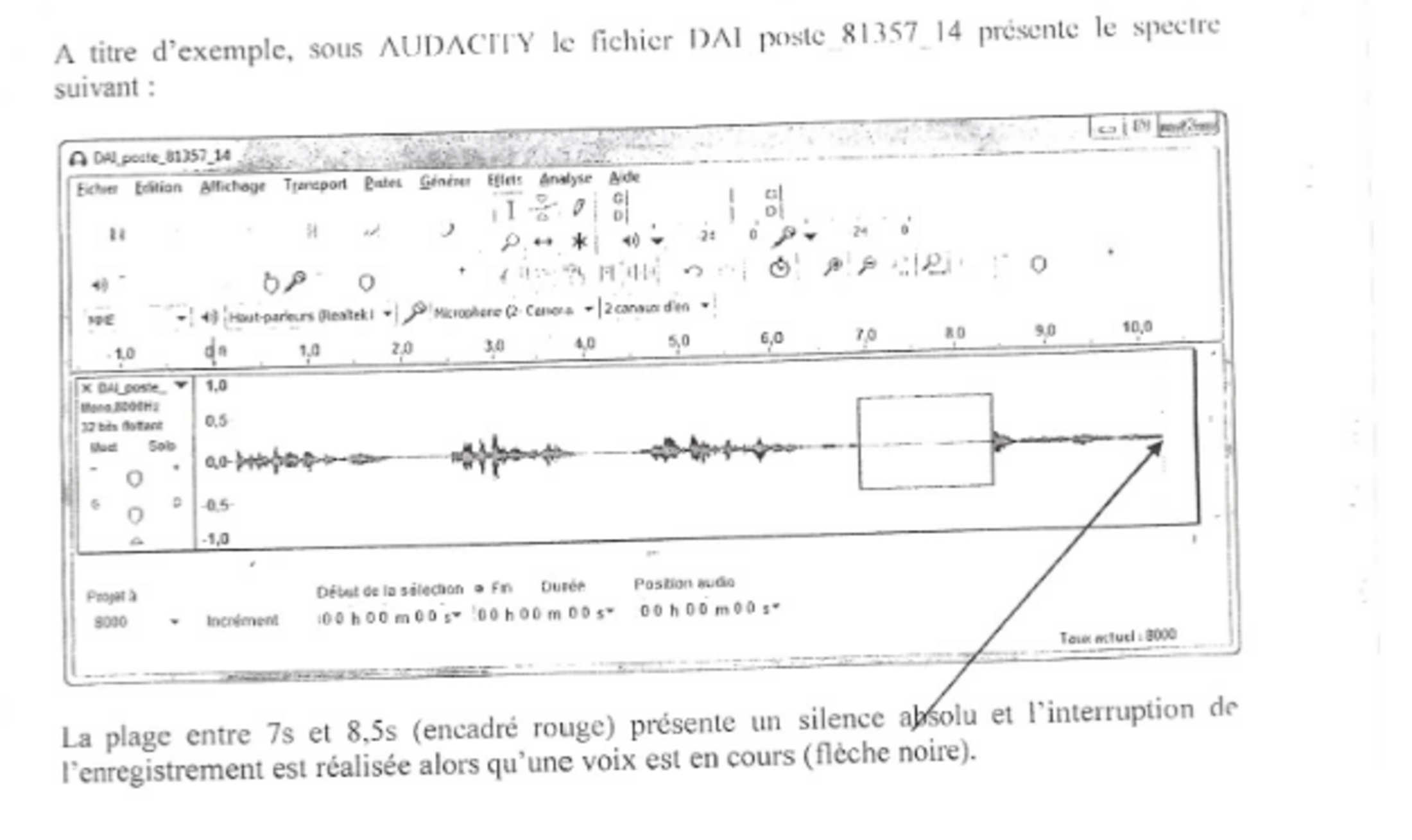

It was only at the beginning of 2012, in the course of appeal proceedings, that David Koubbi was finally able to get hold of the recordings. They were immediately sent to experts Philippe Jacquemin and Michel Roukine for examination. Indeed, they could not be heard otherwise because the recordings were made using a format that is unique to the financial world and which cannot be played on commercially available systems.

Once the recordings were examined they caused some astonishment. For, while the typewritten transcript gave the impression of conversations that were coherent and complete, the recordings – split into 360 different audio files – reveal conversations that are confused, inaudible and sometimes punctuated with significant gaps or silences.

Working from the time and dates of the beginning and end of the recordings, the experts concluded that those made on Saturday 19th January 2008 started at 8.06pm and ended early on Sunday morning at 1.11am. They resumed at 10.21am on the Sunday and finished at 2.11pm. According to their calculations there should, therefore, be 8 hours and 54 minutes of recordings. Jérôme Kerviel has insisted on several occasions that, other than the break at night, the discussions with his Société Générale bosses were not interrupted and that he did not leave the room.

“Yet the total length of the files of the recordings in the presence of Jérôme Kerviel is 6 hours 10 minutes, which allows one to conclude that at least 2 hours 44 minutes are missing,” write the experts. They add: “It is possible for us to assert that Société Générale made excerpts selected on criteria that obviously we don't know.” Their findings raise important questions. How can it be that the justice system never noticed this? Must one conclude that the various people involved in the case and working on what was considered important evidence only used the transcripts provided by the bank, without ever seeing the originals? Why, at the very least, were Kerviel's lawyers not allowed access to the recordings earlier?

'Human intervention extremely probable'

But there are further worrying discoveries, too. For the recordings themselves were cut. And it is not only Kerviel's answers that were cut. On the audio files there are sometimes some long gaps and questions that seem to go unanswered, even if certain words and names are picked up again later as if in reference to answers that have been given but which have disappeared, as the recordings that Mediapart has put on line (see below, in French only) testify.

“Is it chance if the silences correspond to all of Jérôme Kerviel's explanations, the names, services or the brokers who he could have mentioned? [It's] as if the bank had wanted to erase all internal references, in order to show him as the only guilty one,” says his lawyer Davis Koubbi. In a bid to find out more, the experts examined the files' audio spectrum.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Certain audio tracks show complete gaps even though there is a discussion taking place. “That finding seems to show that these zero level tracks are not the result of an automatic detection [system] sometimes put in place to pause the recording...The empty tracks noted don't seem to pause the recording and involve very variable lengths, so they are not the result of an automatic process,” say the experts. They end their report with this conclusion: “On a technical level the multitude of unexplainable empty tracks, compared with the overall process of making these recordings, within the 366 files sent to us, leads us to consider deliberate human intervention as extremely probable.”

“That's all been dismissed. A second opinion was sought and took the experts' claims apart,” says Société Générale's lawyer Jean Veil. The expert who gave that second opinion, David Znaty, has not returned Mediapart's calls. In his report, in which he explains that all the anomalies noted by the experts used by Kerviel's lawyers are linked to the characteristics of the system – provided by NICE – used in the banking world, Znaty concludes: “Société Générale did not make any excerpts...the [missing] 2 hours 44 minutes can be explained by silences longer than 9 seconds and not represented by a signal for reasons of data compression in the system...The silences inside the segments are all less than 9 seconds in length and are silences calculated according to genuine silence and to the [sound] threshold in accordance with the system.”

The initial experts have rejected this analysis, and are astonished that some silences in the recordings are as long as an hour or more. Above all, they say that the explanations given by their colleague to explain the cuts – that they are linked to a system that interrupts itself when there is not enough sound – does not correspond with reality. “The analysis of the files shows that a certain number of stops occur when the sound level of the recording in the fraction of the second before it is high,” they say. This battle of the experts did not, however, raise any doubts with the prosecution last year when Kerviel's legal team first raised the issue; they insisted that there was no case to answer.

Bosses' emails not seized by the authorities

Enlargement : Illustration 6

The recordings are not the only worrying aspect of the legal proceedings that took place against Jérôme Kerviel. The email accounts of his bosses were never seized and were not used in the court case. All the emails in which Kerviel lies about his trading positions to the accountancy service or risk control were included in the proceedings. In these there is clear deception, but nonetheless some of them should have still raised alarm bells. For example, in one email Kerviel explains to someone in charge of accounts that his position involves 73,827 futures. That corresponds to a commitment of 13.7 billion euros. For a trader who normally has a limit of 120 million euros that is a colossal sum. Yet it clearly passed through all the checks.

On the other hand, around 50 emails that showed his discussions with his superiors and alerts from other systems were not included in the proceedings. Some were mentioned during the trial, but clearly without retaining the attention of the court. However, some of them reveal a great deal.

For example, on 4th October 2007 one of those in charge of the stockbroking firm and clearing house Fimat, a subsidiary of Société Générale based in Frankfurt, writes of his concern about the increase in activity in Kerviel's account. Each trader had his own account – Kerviel's had the number SF 581. The email from the Fimat boss is addressed to around ten people in Paris, those who worked in Kerviel's department, in accounts and in the back office. He writes: “Each transaction carried out by Paris must have been accepted during the day by Société Générale...Fimat cannot take the risk of sitting on so many transactions at the end of the day and paying the margin calls on your behalf.” As with email alerts from the derivatives exchange Eurex, warnings from accounts and from management services, this email seems not to have caught the attention of the legal system.

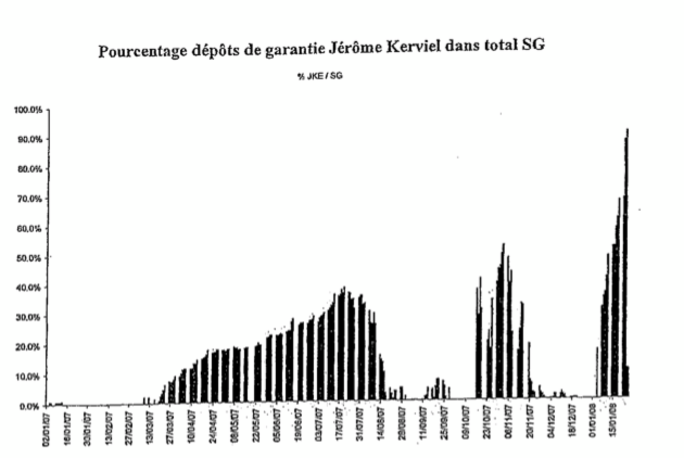

Yet there was one place where the limitless speculative positions held by Kerviel – sometimes going beyond 25 billion euros and ultimately reaching 50 billion euros by January 2008 – could not have escaped notice even if they had been carried out fraudulently; and that's the bank's finance department.

Jérome Kerviel traded in derivatives. Each evening a clearing house, which is completely outside the Société Générale system, establishes the positions held by each banking institution and by each trader – Kerviel had his own account at the clearing house. Because of the nature of the trading, and to guarantee the security of the system and cover risks, every day the clearing house demands 'margin calls', that is, cash payments to cover a part of any potential losses.

Taking into account the vast and exposed positions held by Jérôme Kerviel, the margin calls demanded by the clearing house during the course of 2006 to 2007 have been valued at more than 20 billion euros. It is hard to imagine that the bank's finance department, which had to honour the payments each evening, did not notice such large sums.

'Imposible to claim they could not have known'

During its own investigation into the affair, officials from the regulatory body the banking commission or Commission Bancaire – which has since become the Autorité de contrôle prudentiel - could scarcely ignore the issue. In their report they note: “It is on the face of it surprising that the flow of funds (margin calls and payments, guarantees and final results) generated by Jérôme Kerviel's unusual transactions, which were substantial, did not attract the attention of those in charge.”

The report then outlines the bank's explanations; that margin calls were grouped together on an overall basis, so Kerviel was able to hide his activity in the mass of money involved. And that in January 2008 Kerviel's positions were the opposite of those held by his colleagues, so they were not spotted. The officials admitted that some of those claims were plausible, but added that “closer analytical monitoring of the flow of funds would have enabled alarms to have been raised”. The report barely goes further than that into the issue.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

It is true that banking commission investigators did go into Société Générale's premises at the end of 2007 to study to what extent its risk control system conformed to the cautious industry standards. At the end of December 2007 officials wrote to the bank's president Daniel Bouton to validate its certification in this area, meaning that as far as they were concerned the bank was managing its operational risks perfectly.

If Société Générale did not notice the billions of euros in margin calls generated by Jérôme Kerviel, his bosses did sometimes get concerned about the spending of a few million. In an email from one of the trader's superiors to someone in charge of monitoring the trader, dated 8th January 2008, the executive expresses concern about the commissions being paid to one broker. “I learn that [desk] 2A will pay out 1.2 million euros in derivative clearing fees to Finat Paris. The set up in place envisages dealing with Parel, to whom we pay a flat annual fee,” he writes indignantly. If nothing else, this suggests that executives at the bank were able to spot what was going on when they wanted to.

“It is impossible for a financial institution to explain that it wasn’t able to spot anything. Between the brokers, the accounts, the finance department and the back office a good 20 people follow these movements,” says Jacques Werren, who worked for the futures exchange MATIF. “Taking into account the size of the positions held by Jérôme Kerviel, and taking account of the variations, there was a flow of funds of at least 20 billion euros in a year. That's obviously a position that is monitored every day.” Werren adds: “I tried to explain this during the trial. I spoke for an hour and a half. No one asked me a question. The court did not want to go into it in more depth.”

In its judgement the court dismissed the issue in a page. One reason was that, as the bank had argued, the margin calls were lumped together, which did not allow significant anomalies to be detected, another that the banking commission itself had noted that the detection of the fraud by the clearing house Fimat was not very likely. The judgement pointed out that the clearing house had “no particular interest” in monitoring the movement of funds through accounts to detect fraud and that its “sole preoccupation” was making sure it got paid on time.

In other words, for the court there were no grounds for thinking that the bank could or should have known what was going on.

----------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter