In 2011 the French government passed a law banning the technique of hydraulic fracturing or 'fracking' to extract shale gas from underground rock layers. The move was hailed as a victory for environmentalists and local action groups around the country who had lobbied against the use of a technique they say could potentially cause great harm to the environment.

But could the legality of that ban now be called into question by the country's highest constitutional authority, the Conseil constitutionnel? That is a real possibility after an American energy company Schuepbach used a fast-track procedure to challenge the constitutionality of the 2011 legislation, known as the loi Jacob or Jacob law. The American firm claims that the 2011 law does not abide by the country’s 2004 Environment Charter nor conform to the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Schuepbach held two licences to explore for what are known as 'non-conventional hydrocarbons' in the south of France, at Villeneuve-de-Berg in the Rhône-Alpes region and Nant in the Midi-Pyrénées region. Both were cancelled in October 2011 following the passing of the Jacob law.

The legal challenge was started at the administrative court at Cergy-Pontoise, north-west of Paris, which judged the issue sufficiently “serious” to be referred to the Conseil d’État, the court of appeal for administrative courts. That court has until 19th June to issue a ruling. If it does not, the case will automatically be referred to the Conseil constitutionnel.

Fearing that the law may be overturned, an environmental association is planning to take its own legal action to stop the challenge from reaching the Conseil constitutionnel. “Even if the current law is imperfect, it has the virtue of banning hydraulic fracturing,” says Jean-François Dirringer, vice president of the Association de défense de l’environnement et du patrimoine à Doue (Adepad plus) based in the Seine-et-Marne département – broadly similar to a county – east of Paris. “If the [challenge to the Conseil constitutionnel] demolishes it then oil companies will be free to carry out hydraulic fracturing under the licences.” The ground beneath the Seine-et-Marne is itself being eyed up by oil companies who think it contains reserves of shale gas and oil.

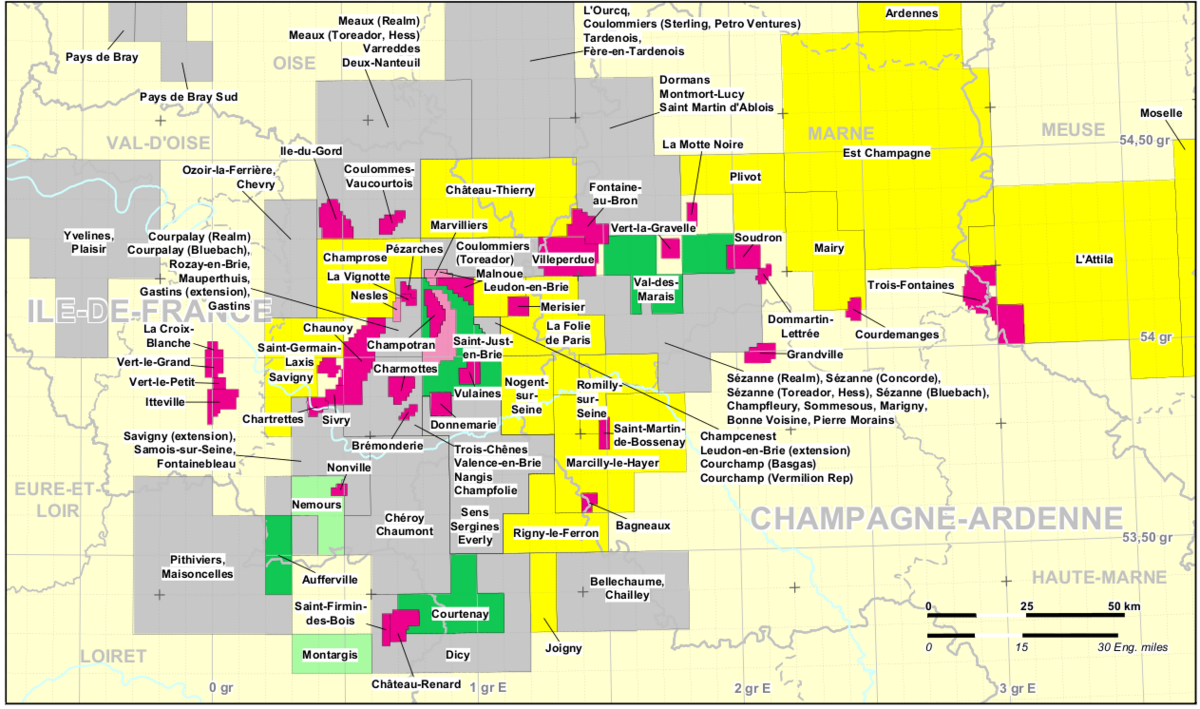

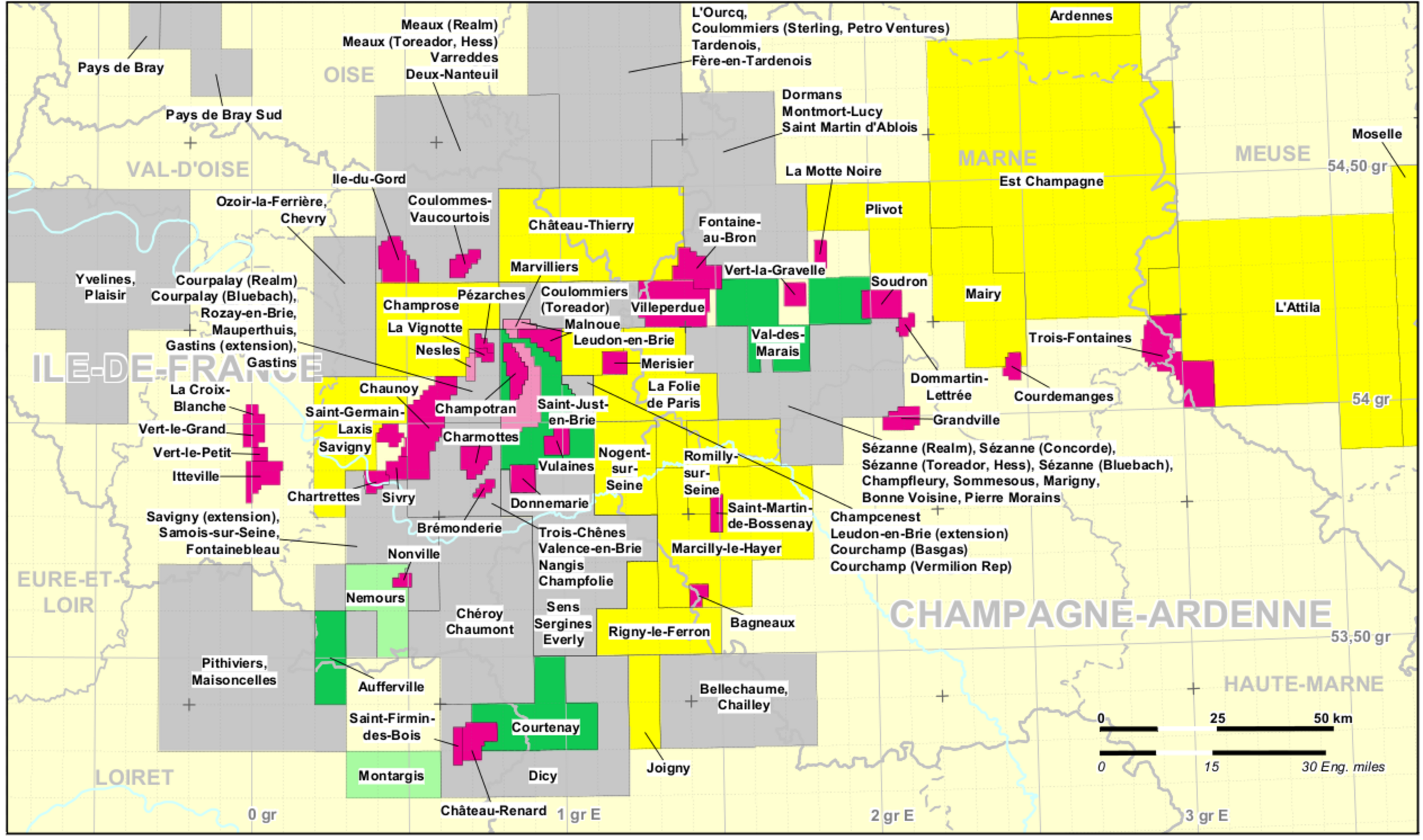

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The association has for several months been looking for backing from local authorities, other activist groups and politicians, and for them to join in the battle and mount a defence at the Conseil d’État to avoid the case ever reaching the Conseil constitutionnel. By joining in the legal case against the American firm the opponents of shale gas would gain access to details of the legal proceedings, whose content has not been made public. But the association has experienced some disappointments along the way.

The regional council for the Île-de-France – the region which contains Paris – has refused to get involved for legal reasons, believing that the action to block the American company will not be admissible before the Conseil d’État. However, Adepad's lawyer Christian Hugo, a renowned specialist in environmental law issues, disagrees with this analysis and says the council has the right to intervene to defend its own interests. “We are still opposed to shale gas, to its exploration and extraction, there's no change in the region's policy,” a council spokesman insists.

The Seine-et-Marne's département council has also rejected the idea of joining the legal action. It believes that it does not have the legal standing to intervene. A council spokesman explains that if the Conseil constitutionnel annuls “all or part of the Jacob law” then the département's president Vincent Eblé – who is also a socialist senator – will “intervene to ensure that the ban on the use of hydraulic fracturing is upheld”.

Precaution or prevention?

The département council executive is already involved with the Île-de-France regional council in litigation against a decree by the local state prefect allowing the oil firm Toreador exclusive rights to carry out drilling at Doue and Jouarre in the Seine-et-Marne. “The decision by the executives of these two local authorities, which have socialist majorities, not to fight against this [referral to the Conseil constitutionnel] could, as a consequence, allow the carrying out of hydraulic fracturing in relation to all the licences granted on French soil before the presidential election,” says the association's Jean-François Dirringer, who is also an activist for the radical left Front du gauche movement.

In September 2012, a few days after the government's high-profile environment conference, environment minister Delphine Batho called on prefects – the state's local representatives – to show the greatest possible vigilance in awarding permits to explore for gas and petrol. “I want you to be careful during the preparation of these [permit] notifications to see that these exploratory works involve exclusively the search for conventional hydrocarbons, whose extraction does not require fracturing,” the minister told them.

Yet in the legal action begun by Schuepbach, the French state appears to have mounted a poor defence. Its legal statement did not convince the court at Cergy-Pontoise to delay the referral of the matter to higher courts, an act that would have stopped the whole case in its tracks. For its part, Schuepbach claims that the anti-fracking law incorrectly applied the precautionary principle. In banning hydraulic fracturing itself, and without setting out the risks that it represents, the law went beyond what it is allowed to do under the constitution, the firm argues. Moreover, the US company's lawyers say, the law has created an inequality in the way the state treats different groups, because the fracturing technique used in geothermal energy is not prohibited. Finally, the company argues that the law does not respect the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen because of its failure to compensate those who own the cancelled licences.

Faced with these arguments the ministry of the environment responded that the 2011 law is in fact based not on the precautionary principle but rather on the principle of prevention, which applies to risks that have already been identified. But this interpretation is the subject of some debate among legal experts, and it is far from certain that the state will prevail in using this argument. As for the absence of compensation this is also a problematic area; for the Conseil constitutionnel the granting of compensation for the consequences of imposing a legal constraint is a fundamental principle.

Thus the ban on hydraulic fracturing - and therefore on shale gas and oil - which has been so publicly supported by President François Hollande and Delphone Batho could well prove to be at risk. This legal vulnerability worries environmentalists at a time when the French employers' organisation Medef - in the form of its president Laurence Parisot - plus companies involved in the national debate over energy and Anne Lauvergeon, the former president of the nuclear energy firm Areva, have been waging a veritable PR campaign in favour of non-conventional hydrocarbons such as shale gas. For them, a legal condemnation of the 2011 ban on hydraulic fracturing would represent a resounding symbolic victory just as a new law on what is called energy transition – the shift towards using renewable energies – is being prepared by the government for the autumn.

--------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter