A Paris court has called for an investigation into the way French bank BNP Paribas handled clients' investments in funds that channelled money to US fraudster Bernard Madoff. BNP appears to have been aware of the risks of investing in the funds but failed to warn clients, while at the same time receiving large commission payments from Madoff, suggesting that the bank may itself be guilty of fraudulent behaviour, the court said.

The claims appear in a January 30th ruling by the appeal court's investigatory chamber, which was shown to Mediapart by a source at the Paris law courts. "According to documents from the Madoff group's US liquidator and of course subject to the investigations still to be carried out, both for the prosecution and defence cases, it now seems that the bank received millions of dollars in exchange for services that were never provided and while it was in possession of information, probably before the deposit of funds by the civil parties, which should have prompted it to investigate BLMIS [Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities]", the ruling says. And it concludes: "Bernard Madoff's own responsibility does not rule out the possibility of fraudulent behaviour by intermediaries such as the BNP."

Legal sources have told Mediapart that it is now highly likely that BNP Paribas will be formally placed under judicial investigation – a French legal move that is one step short of charges being brought.

This represents a major turning point in the French chapter of the Madoff fraud story. Swiss bank UBS is the only major European bank to have so far faced serious charges related to its role as custodian of Luxembourg-based mutual fund Luxalpha, which funnelled large amounts of European savers' money into Madoff’s business.

But while the development is likely to rock the banking world, it comes as no complete surprise, given that BNP Paribas ran Oréades, the first European fund to invest with Madoff, and which operated in exactly the same manner and displayed exactly the same anomalies as Luxalpha.

While Madoff's French victims have launched a number of civil cases in search of compensation for their losses, only one criminal case has been brought in France, in which Martine and Kléber Rossillon accuse BNP Paribas of forgery, use of false documents and breach of trust. But in his preliminary examination of the case, investigating magistrate Renaud Van Ruymbeke has lent towards the view that criminal responsibility lies with Madoff alone, effectively ruling out the possibility of fraudulent behaviour by the bank.

Martine and Kléber Rossillon invested through BNP Paribas in a fund called Groupement Financier Limited, based in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). But Judge Van Ruymbeke concluded that it would be possible to get to the bottom of the case without needing to send an international request for judicial assistance to the BVI. The plaintiffs appealed against this decision and this led to the January 30th ruling by the appeal court's investigatory chamber, the body where decisions by an investigating magistrate can be contested.

Details hidden in a (safe) tax haven

The investigating magistrate will now have to carry out further enquiries to establish whether there is proof that, in addition to Madoff's own fraud, the bank may also have committed criminal misconduct.

But the court's ruling represents an important new development in that it suggests that banks who received large commission payments from Madoff did not recoignise, or did not want to see, signs of fraud that were staring them in the face. The court even suggests that the banks probably had this evidence before clients made their investments. If this is found to be true, any resulting criminal charges are likely to go well beyond the initial complaint of forgery, use of false documents and breach of trust.

BNP Paribas therefore appears to be entering choppy waters after the bank had looked safe from any dangers. It is in rude financial health, with 6 billion euros of net profit in 2011. And former chairman Michel Pébereau aligned the bank closely with the economic policies of French President Nicolas Sarkozy. Pébereau co-authored Sarkozy's 2007 economic programme and the bank has played a key role in implementing Sarkozy's structural reforms. But it is now facing a major legal ordeal that could seriously damage its image, and all because of a case that it initially treated with disdain.

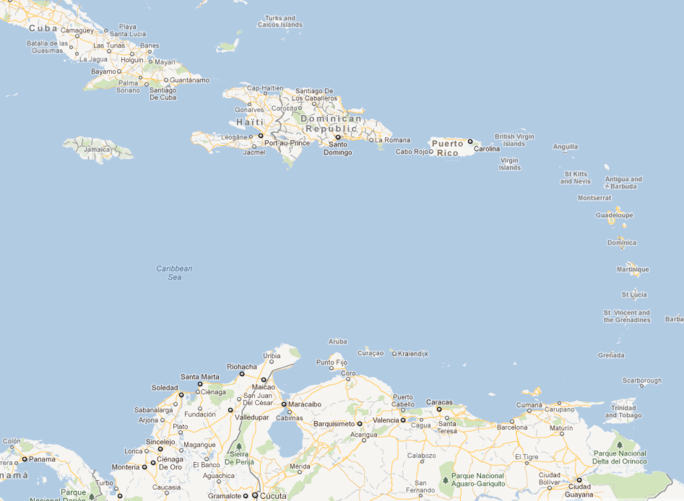

To understand the alleged "fraudulent behaviour" that the court is referring to and the enquiry that Van Ruymbeke must now carry out, it is necessary to go back to the history of Groupement Financier Limited. Most of Madoff's victims in Europe were savers who invested in well-known savings products like Luxalpha. These investors were generally financially comfortable, although not all were wealthy. But some of BNP Paribas's richest clients were advised to invest in the much more mysterious Groupement Financier fund located in Tortola in the British Virgin Islands (click on map below).

Enlargement : Illustration 2

As is shown by a Groupement Financier confidential memorandum, this fund displays a number of features which draw attention. Apart from the fact that it is incorporated in the tax haven of the British Virgin Islands, it was only open to a small number of investors, with the minimum investment set at 1 million dollars, making the Groupement Financier a sort of Luxalpha for the mega-rich.

There are further similarities between the two entities. Luxalpha was managed by a company called Acces International Advisors Limited (AIA), and the Groupement Financier statutes show that AIA was also its investment manager.

BNP Paribas disregarded the fund's statutes

The AIA group was founded by Thierry Magon de la Villehuchet, and other internal Groupement Financier documents explicitly name Magon de la Villehuchet as a director of the fund, alongside his friend and business partner Patrick Littaye. Magon de la Villehuchet was previously chairman and CEO of Crédit Lyonnais Securities in New York, and also worked at Banque Paribas in the early part of his career. He put many wealthy French people in contact with Madoff and eventually took his own life in his Madison Avenue office when the Madoff scandal broke in December 2008.

Documents obtained by Mediapart reveal a number of surprising elements. In the cases that have come to our attention, clients did not invest directly in Groupement Financier, and BNP Paribas acted as their sole point of contact. These clients say they knew nothing of the Groupement Financier confidential memorandum and its restrictions, and were confined to dealing with BNP Paribas.

Two internal BNP Paribas documents confirm this version of events. These documents, dated June 26th 2007 and July 9th 2008, are subscription orders sent to the fund by the bank's private banking and wealth management department (Banque privée-Gestion de fortune), and do not mention any client names. Thus the names of the real investors do not figure in the registers of the fund, which was only aware of the banks that were sending it subscription orders (some other elements that appear in the documents have been concealed by Mediapart).

Furthermore, in some cases BNP Paribas did not respect the minimum investment level of 1 million dollars. The order dated June 26th 2007 is for an investment of 500,000 dollars and Mediapart has learnt of a similar investment of 700,000 dollars made in 2004. This raises the question of whether BNP Paribas was selling small parcels of Groupement Financier shares to its clients while keeping them unaware of what was going on with the fund.

The story is further complicated by a change in the fund's statutes in August 2007. Until then, all types of private investor could subscribe to the fund, but under the new statutes it became a purely professional fund. "The shares may therefore only be issued to professional investors," according to the new statutes, which defined a professional investor as "a person whose ordinary business involves, whether for their own account or the account of others, the acquisition or disposal of property of the same kind as the property or a substantial part of the property of the Company".

The new statutes limited access to the Groupement Financier to banks or financial institutions. Another change revised downward the $1 million minimum investment requirement. "[...] the minimum investment of the majority of such investors must not be less than US$100,000" reads the document. These two provisions were perhaps aimed at bringing the statues into line with earlier practices that were in violation of the fund's original statutes.

But there was an exception to the fund's restricted access. A new category was also allowed entry to the Groupement Financier: the professional investor, defined as "a person who has signed a declaration that he has net worth (whether individually or jointly with his spouse) in excess of US$1,000,000 or currency equivalent and that he consents to being treated as a professional investor ".

Investigations to move to the British Virgin Islands

The terms are clear. In such cases, each investor will have to consent, in a signed declaration, to the statute of professional investor. The purchase application that each investor must sign to invest in the Groupement Financier also draws attention to the provisions of the Confidential Memorandum in which the high-risk nature of the investment is clearly spelled out. "The Applicant has carefully read and fully understands the Confidential Memorandum, is fully capable of assessing and bearing the risks involved," the purchase order states.

In those cases investigated by Mediapart, French investors did not know about the changes in the fund's statues, or about the Confidential Memorandum. They did not consent in a signed declaration to the statue of professional investor. In short, everything continued as before, as can be seen in the second purchase application mentioned above. For a total investment of 400,000 euros, these French clients of the fund had but a single contact – their bank.

The question is thus raised as to whether, the day after the FBI discovered the fraud and arrested Bernard Madoff, on December 12th 2008, BNP Paribas attempted to obfuscate the fact that it bent the rules of the fund by allowing access to investors that, without its assistance, would never have been eligible. This is one of the threads the Paris court has now asked Judge Renaud Van Ruymbeke to untangle. It is asking him to investigate in order to verify whether or not BNP Paribas forged documents to cover-up the fact that Martine and Kléber Rossillon were not, in fact, shareholders of Groupement Financier Limited. By becoming a shareholder itself, BNP Paribas could have allowed the Rossillons entry into a fund that, without the bank's intervention, they could not have accessed. Thus, thanks to BNP Paribas, Bernard Madoff was brought a higher number of clients and the bank's commissions were that much more substantial - to the extent that its vigilance may have been dulled.

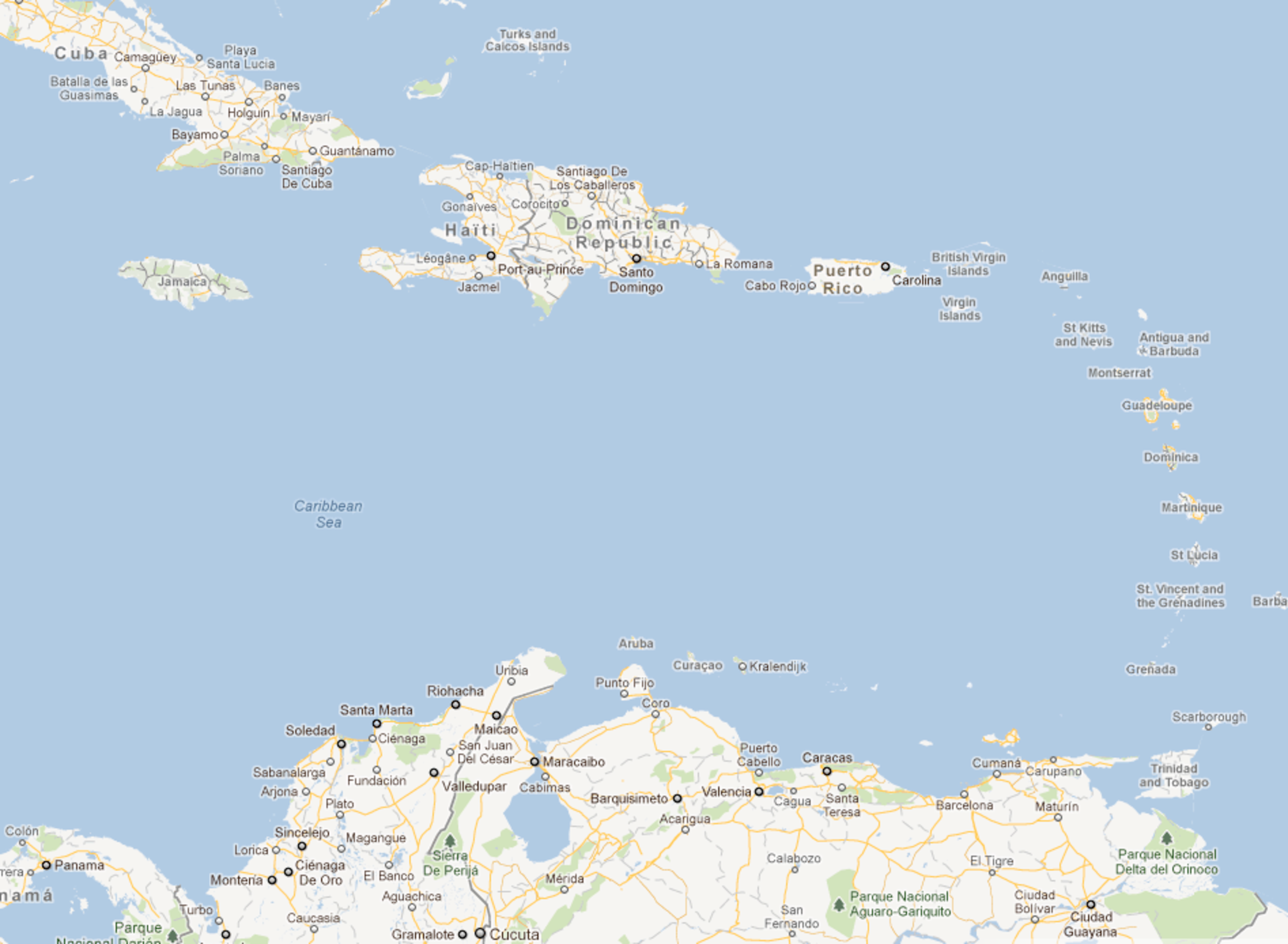

Evidence of forgeries was uncovered during the investigation. When Madoff's Ponzi scheme was discovered, Véronique Lartigue, the lawyer defending Madoff's French victims, filed a slew of motions in favour of her clients and finally obtained the purchase orders for Groupement Financier Limited which contain the – forged – signatures of Kléber Rossillon (see above left). These forgeries were the starting point of a warrant issued on March 26th 2009 for police to search BNP headquarters following a lawsuit filed by Oliver Metzner (the lawyer for the same clients as Lartigue but in a criminal lawsuit). While the search was highly publicised at the time, the hubbub soon died down.

Now the court has given the case a spectacular kick-start. Its ruling shows that the signature of Kléber Rossillon was forged twice. The first time, it was forged and then digitalised so that it could be duplicated. The second time it was used, the signature was highlighted to make it appear more authentic.

The Paris court's ruling, giving new impetus to a case that had become stalled, is significant for three reasons. First, the ruling demonstrates that the forgeries can be corroborated. It further shows that BNP Paribas is under suspicion of having succumbed to the draw of substantial commissions leading to a lack of vigilance or passive behaviour on its part. Finally, it calls on Judge Van Ruymbeke to continue his investigations.

He will now have to issue Letters Rogatory (international investigation warrants) with the authorities of the British Virgin Islands in order to gather the necessary information about the fund and to assess the amounts of the bank's commissions. It is for this reason, according to judicial sources consulted by Mediapart, that BNP Paribas cannot escape being formerly placed under investigation.

The court's ruling is all the more serious for BNP Paribas because it makes specific references to procedures launched in the United States by the liquidator of the Madoff Group. As mentioned earlier, the ruling states: "According to documents from the Madoff group's US liquidator and of course subject to the investigations still to be carried out, both for the prosecution and defence cases, it now seems that the bank received millions of dollars in exchange for services that were never provided and while it was in possession of information, probably before the deposit of funds by the civil parties, which should have prompted it to investigate BLMIS [Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities]".

US lawsuit against BNP Paribas

In the US, the Trustee of assets for the Madoff liquidation, Irving H. Picard, has filed a lawsuit against BNP Paribas and others regarding another fund, Legacy Capital, which also invested in Madoff products. In his brief, reproduced immediately below here, the liquidator is highly critical of the fund managers, including BNP Paribas.

Picard begins his long list of questionable behaviour by noting that financial establishments had evidence showing fraud on the part of Madoff but did nothing about it. "[...] all Defendants were on inquiry notice of BLMIS’s fraud based on: Lack of disclosure of counterparties to alleged trades" and because "Madoff left hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars, in traditional industry standard management and performance fees on the table while taking only modest commissions for his investment management services," the brief states. This last argument clearly impressed the French appeal court magistrates, as demonstrated in their ruling, along with another important comment in Picard's lawsuit, even though it concerns a different case. "Defendants have all been unjustly enriched. [...] Defendants earned millions from fees and interest. These fees and interest took the form of management fees, custodial fees, advisory fees, incentive fees, and interest payments. None of this money has been returned to the Trustee for distribution to BLMIS’s customers who lost billions of dollars in the Ponzi scheme," the lawsuit reads.

Contacted by Mediapart, BNP Paribas provided the following written reply: "BNP Paribas does not intend to comment on a procedure that is the subject of an on-going investigation. It wishes, nevertheless, to point out that it has never been placed under investigation in this affair in which the Bank's role was limited to carrying out the instructions given by clients who invested in a Madoff feeder fund on the recommendations of a financial advisor who is totally independent of BNP Paribas. Judge Van Ruymbeke has carried out investigations for nearly two years and has concluded that the criminal responsibility of BNP Paribas cannot be implied. Today, the [appeal court's] investigatory chamber is asking Judge Van Ruymbeke to continue the investigation. BNP Paribas, a simple assisted witness in this case, awaits with serenity for justice to be done."

Nevertheless, the appeal court investigatory chamber’s ruling represents a landmark decision in the case. In its January 30th ruling, the court mentions substantial commissions received by BNP through other Madoff funds in which it was either a manager or a custodian. In other words, it suggests that bankers cannot, with impunity, practice selective amnesia at the expense of their clients. On the one hand, BNP Paribas, either directly or through subsidiaries, fulfilled the role of custodian and/or Madoff fund manager – through the Oréades fund in Europe or with Legacy for off-shore investment – for which it received unusually high commissions. These should have attracted its attention, but may have been the price paid in return for its silence over what today appears as serious and corroborated evidence of Madoff's fraud.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

On the other hand, BNP Paribas, playing the role of intermediary, unflinchingly executed its clients purchase orders without informing them of what it knew through its other functions. The court suggests that the argument of the existence of Chinese Walls does not hold water. The bank cannot receive millions of dollars in exchange for ignoring unethical behaviour, then behave like a naïve victim when the fraud is revealed; especially if it acted as a screen and, unbeknownst to its clients, gave them access to a fund (Groupement Financier) to which they were ineligible, or if it omitted to inform them of the liability waiver as was the case with Luxalpha.

France's – and Europe's – leading bank could be implicated in behaviour that goes beyond simple negligence and the legal consequences for BNP Paribas could be significant. In the midst of France's presidential campaign, this is very negative publicity. "You're not speculating with our money on the markets, all the same?" runs a question in a current BNP ad campaign, themed 'Talking Straight' (click on video above left). It turns out that the bank has been – and that may not be the worst of it.

-------------------------

English version: Steve Whitehouse and Patricia Brett

(Editing by Graham Tearse)