As in many recent conflicts in which Western powers have intervened militarily in other countries, France has been accused by some observers of furthering its energy interests and economic investments in the Sahel through its war against Islamist militants in Mali that began on January 11th.

President François Hollande has unequivocally denied the suggestion, saying : “France does not have any interests in Mali. It is not defending any economic or political calculation.”

The truth, however, is somewhere in between. France has few interests in Mali, but it does have others in the broader Sahel region. Above all, it has a major interest in the region's stability, both because important energy issues are at stake and to halt the proliferation of armed groups threatening terrorist acts.

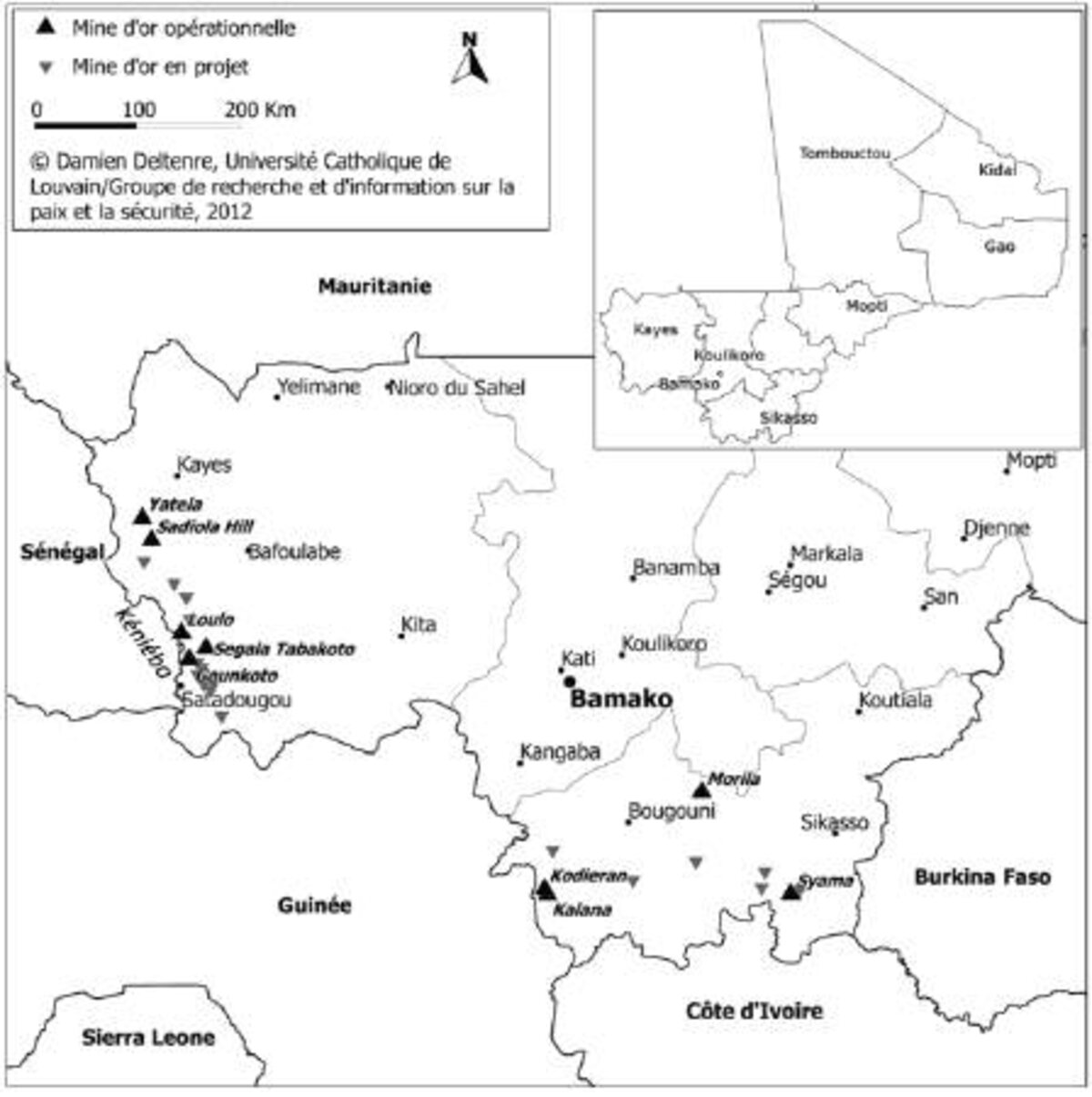

Mali's sole proven resource is gold. It is the third-largest gold producer in Africa, mining 43 tonnes in 2011, equivalent to 15 % of its gross domestic product (GDP) and 70 % of its exports. According to the Belgian think-tank Group for Research and Information on Peace and Security (GRIP), Mali has nine working gold mines owned by eight companies from seven different countries, none of which are French.

However, a subsidiary of French construction firm Bouygues, Société Malienne d'Exploitation (Somadex), does have some involvement in certain mines. Altogether Mali's mines employ some 12,000 people – although, as is often the case in Africa, there is a significant amount of informal, unregulated activity, and there are probably about 200,000 people eke out a living in Mali's gold sector.

Almost all Mali's gold mines are concentrated in the south-west of the country, as shown on the map above, which means they have remained under Bamako's control and have operated normally, even after Islamist rebels took control of the north in January last year and following last March's coup d'état.

Workers in Mali's gold sector often endure appalling working conditions which are regularly the subject of alerts from numerous non-governmental organisations, like this report from the International Federation for Human Rights. During the 1980s and 1990s the sector was opened to foreign companies, and current mining regulations favour the interests of mining companies over those of the country itself. In neighbouring countries gold deposits are marginal, although there is some small-scale gold mining in Niger.

According to the French state-run geological institute, the BRGM, Mali also has potential to mine iron, bauxite, manganese and phosphates, as well as uranium, the key ingredient for nuclear fuel (see page 2). But all this remains at the stage of geological indices and to date, no companies have embarked on either exploration or mining for these minerals in Mali. Again, these resources are to the south of Timbuktu and therefore away from the rebel-held areas in the the north where there is a different geology.

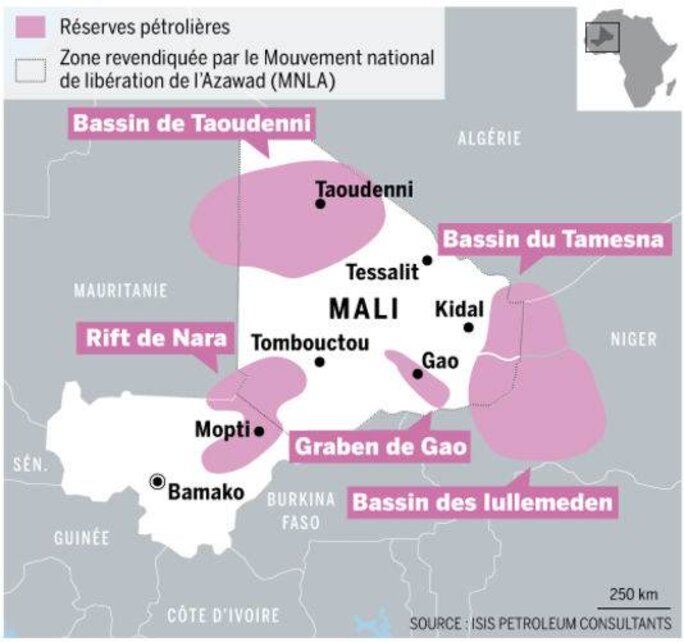

Oil and gas are, of course, the dream finds in the energy sphere, and Mali is no exception to the rule. But although several underground oil deposits have been identified, oil production is currently non-existent there. In the early 2000s the Malian authority for promoting oil research, Aurep, which is part of Mali's Ministry of Mines, sold exploitation permits for 29 zones. Algeria's Sonatrach and Italy's ENI were the only major oil companies to seek such permits, and for the moment neither has undertaken any drilling.

So despite the hopes of some oil companies that Mali would be the new oil Eldorado, nothing has yet confirmed its potential in this sector. There are several reasons for this. Mali is landlocked and isolated, infrastructure in the north is underdeveloped, the geopolitical environment is dangerous – as can be seen today – and not least, oil multinationals already have dozens of unused exploitation permits in much more promising regions, like Libya and the Gulf of Guinea, for example.

Among some of Mali's neighbours, apart from Algeria which is already a major oil producer, the oil industry's hopes are beginning to bear fruit. In 2006 Mauretania began to sell crude oil pumped by an Australian company from offshore wells, but not from its desert. And Niger began crude oil production in 2011, under the auspices of the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), which agreed to build a refinery in the country, a condition the American giant Exxon had refused.

“The entire Sahel zone is under-explored”, commented Philippe Gombert, an official at BRGM's international cooperation department. “The prospecting that is getting underway in Niger and Mauretania is very recent.”

Uranium is the real prize

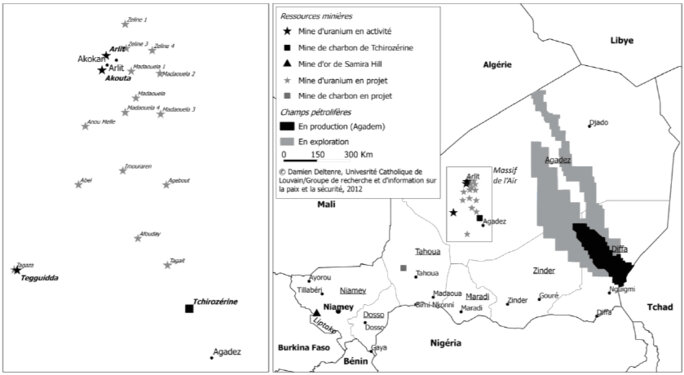

Last but not least, uranium has been identified as a potentially profitable resource in Mali. But in the region, all eyes are focused on Niger, currently the world's fifth largest uranium producer. French nuclear group Areva, which over a long period had a monopoly on mining Niger's uranium ore, still extracts around a third of the country's annual uranium production from the Arlit and Akouta mines, making it the second largest employer after the government of Niger itself – although it only employs 1,500 people.

In 2014 Areva is due to begin mining at Imouraren, which is slated as the second largest uranium deposit. Areva has invested heavily in the site – 1.2 billion euros – and in the process, there has been friction between the French firm and the government of Niger. Imouraren gives Niamey the perspective of becoming the number two uranium producer at a time when its fiscal receipts are a source of concern. Since the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan in March 2011 uranium prices have tumbled to $50/lb from $70/lb.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Areva's priorities are twofold : to counter competition from increasingly active Chinese companies and, perhaps more importantly, to guarantee the supply of all the uranium France needs. The country has the second largest number of nuclear power plants in the world, and these supply some 75 % of its home electricity demand. Indeed, without the personal intervention of former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, a Chinese company would probably have won the Imouraren concession.

These high economic and energy independence stakes for France play out against the background of a Touareg rebellion and kidnappings of Westerners by AQIM (Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb). French troops are also to be given the task of protecting Areva's sites in Niger.

However, in Mali, geologists have only indications of the presence of uranium. Last month Le Figaro reported that Rockgate, a Canadian mining company, had been granted an exploration permit for a uranium deposit at Falesa, 350 kilometres west of the Bamako, near Mali's borders with Senegal and Guinea. “French giant Areva has carried out exploration in the region of Saraya on the Senegalese side”, the daily added. It also quoted Michèle Rivasi, a European MEP from the French Green party Europe Écologie-Les Verts, saying that Rockgate and Areva had forged an agreement. This was denied by Areva.

It therefore appears clear that France did not intervene in Mali in order to secure mineral or energy resources that are quasi-inexistent. Any potential in the country is too far in the future to reasonably enter into the equation. On the other hand, it is just as clear that at a regional level, in the Sahel area comprising the north of Mali, the east of Mauretania, Niger and the southern parts of both Algeria and Libya, the energy issue is significant.

Kidnappings by AQIM, or the breakaway group Mujao, target oil, gas or mining complexes, as seen recently at Arlit in Niger and In Amenas in Algeria. The presence of Jihadists and Touareg rebels is clearly a factor holding back oil and gas exploration and the construction of transport infrastructure – such conditions do not lend themselves to building pipelines.

Oil and gas resources may still be a mirage, but the potential clearly exists. Chad, which is further to the east but shares the same geological structures with the rest of the region, has already shown the way, and Niger and Mauretania have geared up on this front. Mali, however, is lagging, in part because of its isolation – landlocked, with inadequate infrastructure – and also because oil and gas is more easily accessible elsewhere.

It is uranium that is undoubtedly the real prize here, given the ore deposits discovered in Niger and the potential for something similar in Mali. It is a crucial resource both for France and energy-hungry China.

But the armed groups that have made their base in the Sahel, and in particular the north of Mali, have upset the order of things. They clearly represented a political threat – they succeeded in capturing half a country and to subject part of its population to their rule – but they also represented a terrorist threat.

And on an economic level, they threatened the free circulation of people, goods and merchandise, the mantra of modern Western economies. However, in this context, France's economic interests in the Sahel encompass something considerably broader than might be suggested by the list of French investments in Mali.

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)