For centuries, Westerners have viewed Timbuktu as a quasi-mythical city, whose very remoteness has shrouded it in mystery and mystique. In demolishing various saints’ tombs in this “pearl of the desert”, the Islamist group Ansar Dine has simultaneously destroyed the shrines of other Muslims, which they deem heretical, and raised a challenge to the West, which had just put the “City of 333 Saints” on the UNESCO List of World Heritage in danger.

Historian Charles Grémont is a researcher at the French research institute the IRD (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement) and a research associate at the African research centre CEMAf (Centre d'Études des Mondes Africains) and has carried out extensive fieldwork in northern Mali. In the following interview, Grémont gives the background to the complicated situation and the current upheavals in northern Mali.

Mediapart: What exactly do we know about what’s going on these days in northern Mali?

Charles Grémont: A lot of news does get around and the phones work, though it’s still pretty hit or miss right now. But there’s a dearth of field data because there haven’t been any researchers or journalists on location for months now. And there are very few Malian journalists from the south going up to the north.

These days we’ve been hearing a lot about people from the MUJAO [Editor’s note: Unity Movement for Jihad in West Africa ] booby-trapping the roads out of Gao with mines to prevent the population from leaving, but that was not corroborated by the people I managed to reach in that city. It’s often hard to distinguish between rumours and established facts. So you’ve got to be careful because rumours invariably affect people’s lives one way or another.

Mediapart: Why is the “Salafist’”Ansar Dine group attacking saints’ tombs and mosques in Timbuktu?

C.G.: These saints’ tombs are figures of the Islamic orders. The predominant regional branch of Islam is Sufi, with notably the presence of the Sufi order or brotherhood of the Qadiriyya. This is a branch of Islam that’s very open to science and culture. It represents the region’s cultural heritage and the way people live Islam there for the most part, but which is now deemed heretical by the Salafists.

Mediapart: How would you explain the symbolic impact of the destruction?

C.G.: From the 16th to the 18th century, Timbuktu was a vital crossroads on the trans-Saharan trade routes. Owing to its location, the city also became a centre of Koran study, with a great many schools there. It attracted scholars, and this tradition continued to an extent, even when the main axis of trans-Saharan trading began shifting further east in the second half of the 17th century.

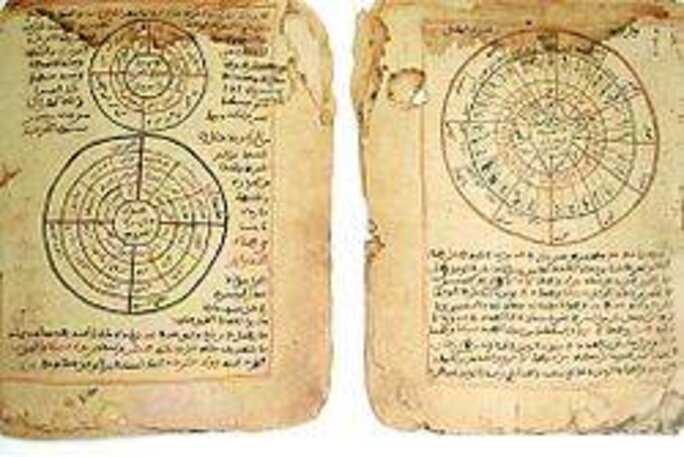

That explains why the city now holds precious old manuscripts, even if their importance has been exaggerated against the backdrop of Western legends that prompted the European exploratory expeditions of the early 19th century, and rekindled interest in the place more recently, in the late 1990s, on the part of the United States and under the aegis of UNESCO.

The idea of Timbuktu as a “holy city” is a Western construct. In a town like Djenné, a little further south, one also finds the mud architecture of which the tombs destroyed in Timbuktu have become the symbols, especially since the city was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1988.

The “myth” of Timbuktu is a late construct that grew up after the city’s golden age. In fact when René Caillé, known for the [1830] publication of his famous Voyage à Timbuktu (see right), first entered the city [disguised as a Muslim], he expressed his disenchantment at a city that was rather falling into ruin.

Mediapart: This destruction is often compared to that of the Bamyan Buddhas by the Taliban in Afghanistan. However, although both cases involve the destruction of exceptional world heritage, isn’t there a difference in the sense that the Buddhas were disconnected from local beliefs, which is not the case of the tombs in Timbuktu?

C.G.: These tombs clearly correspond to the history of the city’s inhabitants. But their troubles did not begin with this destruction, and when I talked to inhabitants on the phone, the tombs were not the main topic of our conversations. When you’re struggling to find a little food or medicine (local health services haven’t been up and running for several months now), the destruction of a tomb certainly causes some indignation, but that concern pales next to their daily sufferings.

In addition, those inhabitants of Timbuktu who know how to read manuscripts in Arabic and are really aware that historical treasures are in jeopardy are a minority.

Tuareg, Arabs, Songhai – the many peoples of northern Mali

Mediapart: Is Timbuktu a Tuareg city?

C.G.: The name of the city does come from Tamasheq [the Tuareg language], and simply means “the woman from Buktu”: it’s the name of a woman whom they may have met in the 12th century on the site of the present-day city.

Naturally, the Tuareg aren’t the only tribe in northern Mali. There are Arabic speakers as well, Arabs from the Western Sahara, also known as Moors. There are also a great many Songhai, who make up the majority in the cities of Timbuktu and Gao and throughout the Niger River valley, and are part of the Azawad territory claimed by the Tuareg of the MNLA [National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad).

Relations between these groups are complex, and they can’t be pitted against one another. There was a high degree of complementarity between the Songhai of the Niger valley and the Tuareg, and, over the course of the 19th century, for example, there was no opposition between these groups, but rather a situation in which certain Songhai and Tuareg were allied against other Songhai and Tuareg. At the time of the colonial conquest [late 19th/early 20th century], the French tried to pit these groups against each other, and counted them separately for census-taking purposes as “nomadic” groups on the one hand and “sedentary villages” on the other.

Since the 1990s, more rigid divisions have grown up between the communities. Beginning in 1994, we’ve seen the Songhai arm themselves and set up “self-defence” militias. Some of them apparently made up the armed branch of the MUJAO in the latest attacks carried out in Gao. They had suffered a great deal at the hands of the MNLA Tuareg, whom they accused of looting, even rapes –accusations vehemently denied by the MNLA leadership.

Mediapart: What is this group, Ansar Dine, which is now attacking the tombs in Timbuktu?

C.G.: Unlike the mostly Arabic-speaking MUJAO, Ansar Dine is for the most part made up of Tuareg people. The group is headed by a former leader of the 1990s rebellions, Iyad Ag Ghaly, who is originally from Kidal. This movement is often presented as the Islamist counterpart to the secular MNLA, but in reality there is some interchange between the two. In fact, we observe various forms of political opportunism inducing certain Tuareg to join the group because it is doing well and has far greater financial resources, rather than for religious reasons.

Political and matrimonial alliances are key to the mindset in these regions, which are subject to drastic changes in climate, so it’s important to be able to count on the help of parents and neighbours there to cope with all the imponderables, which are indeed omnipresent. So Ansar Dine isn’t made up entirely of fanatics chanting “God is great” as they demolish the tombs, even if the rise of religious fundamentalism is quite real here as elsewhere in North and West Africa.

Mediapart: In 2011 you co-authored a report entitled “Contestation armée et recomposition religieuse au Nord-Mali et au Nord-Niger “[“Armed Protest and Religious Reconfiguration in Northern Mali and Northern Niger”]. Does the deterioration of the situation in northern Mali come as a surprise to you?

C.G.: I’m not necessarily surprised by the nature of what’s going on, but by the extent of it, yes! These are outbreaks of “Islamism” or “Salafism” that were already latent in embryonic form. They do not only affect the Tuareg, but the whole of West Africa. We need to distinguish, moreover, between the Al Qaeda-linked movements and the Tablighi Jamaat, which comes from the Indian subcontinent and gained a foothold in Kidal, through Pakistani preachers, at the tail end of the 1990s when I was doing my fieldwork down there. The movement was originally “quietist” or “pietistic”, so to speak, without any political affiliation. Has it become the conduit for more violent and politicised movements of the Salafist stamp? Not necessarily, though that has sometimes been the case.

‘Kalashnikov trade unionism’

[asset|aid=158162|format=image|formatter=asset|title=|align=right|href=]Mediapart: Is there a continuity between what’s happening now and what occurred in 2006 in the Malian cities of Ménaka and Kidal, with the attacks on the army and police camps, or during the rebellions carried out by a great many Tuareg in the 1990s?

C.G.: In the 1990s, no official call for independence was actually made, even though that was very much present in the hearts and minds of many combatants. In 2006, the Tuareg rebellions (in Mali as in Niger) were not based on any territorial political claims, but more on a call for social justice and development, as championed by the Tuareg Democratic Alliance for Change in Mali and the Niger Movement for Justice in Niger.

What we saw there was the failure of the peace accords that were attempted from 1996. After the rebellions of the 1990s, the Malian central government tried to “buy” peace by doling out government posts, gifts and privileges to some leaders of the former armed fronts, who redistributed them to their supporters. That initially led to deeper integration of the Tuareg into the Malian government, with symbolic measures, lots of money for development, posts in the army and in customs and so on.

[asset|aid=158156|format=image|formatter=asset|title=Amadou+Toumani+Touré|align=left|href=]

But then those efforts failed because the central government, especially President Amadou Toumani Touré, sought to divide in order to rule more effectively, by playing on existing divisions and oppositions between and within the various groups in the region, particularly among the Tuareg themselves, favouring one particular group over another. This was in perfect continuity with the divisive approach devised and applied by the French colonial government.

So the dividends of the peace agreements were shared out unequally and that bred new tensions. Some of those who had taken up arms in the 1990s felt left out, while others who had not fought got rewarded. The resumption of hostilities in 2006 corresponded to what might be termed “Kalashnikov trade unionism”, in which each group took up arms again to obtain jobs and money.

Mediapart: Were the realities of northern Mali utterly transformed by the advent of AQMI [Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb] and drugs trafficking?

C.G.: The context changed considerably with the rise of drugs trafficking, which is a whole chain in which the Sahel Saharan area is but one link. As for AQMI, its historical core is the Algerian GIA [Groupe Islamique Armé – Armed Islamic Group ]. All that is dangerous for the youth in the north who have no work and are susceptible to the lure of goods and money. These societies in the north were not living in complete isolation, but in these impoverished areas, the herding- and farming-based economy in particular was upended by the trafficking.

Although it is very hard to gauge the extent of trafficking in the local economy, and although trafficking is not new to the Sahara, it has definitely taken on a wider amplitude now, starting with cigarettes in the 1980s and 1990s. It then reached another level with the trafficking in cocaine in particular. The financial stakes are such that everyone is getting in on the action.

Although there is no way to verify this, circles close to the Malian president were probably involved as well when the infamous drug planes touched down in northern Gao, with complete radio silence for several days on the part of Bamako [the Malian capital]. The drugs trafficking is now centred in Gao, because there’s a valley leading out of Gao that allows passage to Algeria, and from there to Egypt, the Middle East and Europe.

According to what friends of mine on location are telling me, the MUJAO is now by and large in the grip of drug traffickers. At any rate, they have a lot more money than the MNLA and are using it to wage a military offensive to drive the MLNA Tuareg out of the city of Gao, paying Songhai youths, in particular, to do the job. They are also playing on an old stereotype, one in use since colonial days, that classes the Tuareg as bandits and, in this context of rampant chaos, claiming that Islam is going to cleanse all that, even though they themselves are certainly involved in the trafficking.

-------------------------

English version: Eric Rosencrantz

(Editing by Michael Streeter)