Speculation continues to surround the motivations of Bernard Arnault, founder and chief executive of French luxury goods group LVMH and France’s richest individual, in applying for Belgian nationality.

The controversy surrounding his move, revealed earlier this month by Belgian daily La Libre Belgique and swiftly confirmed by Arnault himself, has highlighted the attractiveness of France’s northern neighbour for those seeking to avoid French taxes, and notably its wealth tax.

Arnault, after an initial delay, finally told the media that he would for the moment continue to pay his taxes in France after he becomes a dual French and Belgian national, although what his long-term plan was remained a mystery. Nevertheless, if he does set up home in Belgium, he would be following in the footsteps of a number of successful French businessmen, including Bernard Darty (founder of the Darty electrical goods store chain), Philippe Hersant (head of the Hersant Média group), Lofti Belhassine (former boss of French airline Air Liberté) and members of the Taittinger family of prestigious champagne producers.

The tax-avoiding attractiveness of Belgium for the French rich is nothing new. But since the arrival of France’s socialist president, François Hollande, who has announced a 75% tax on those earning an annual 1 million euros or more, the country’s wealthy have begun pointing north. Marc Simoncini, founder of one of Europe’s most successful online dating services, Paris-based Meetic, is one of them who has publicly threatened to expatriate himself to Belgium if Hollande goes ahead with his promised fiscal reforms.

While Arnault was slammed by Hollande for lacking patriotism at a time of need, and French finance minister Pierre Moscovici more modestly declared Arnault had “failed to be exemplary”, the controversy has fuelled a lively debate in Belgium itself over the country’s growing semi-tax haven status in Europe, just weeks before the socialist government faces its first test in local elections.

On May 2nd, just before François Hollande’s widely forecast presidential election victory, Brussels-based tax lawyer Manoël Dekeyser, whose law firm Dekeyser & Associés was described by the paper as “specialized in assisting French tax evaders”, told Belgian daily L’Echo that his practice had seen a steep rise in the numbers of French people enquiring about moving to Belgium. He recalled that in the years following the introduction of a special wealth tax in France, the Impôt de solidarité sur la fortune (ISF), half of his firm’s clients were French.

“After the election of [Nicolas] Sarkozy in the presidential elections in 2007, this number fell,” he explained. “Since the past few months, we’re back to around 25% of French among our clientele. The number of phone calls from French people considering setting up home in Belgium has recently tripled.”

Based on his own experience and the interest recorded among his colleagues, Dekeyser estimated that between 1,000 and 1,500 wealthy French citizens were at that time considering moving to Belgium for tax reasons.

Unofficial estimates from the same sources suggest some 5,000 wealthy French were already domiciled in Belgium for fiscal reasons. “On average, their wealth is estimated at between 20 million and 30 million euros,” said Dekeyser. This compares with a total number of French expatriates in Belgium of around 250,000.

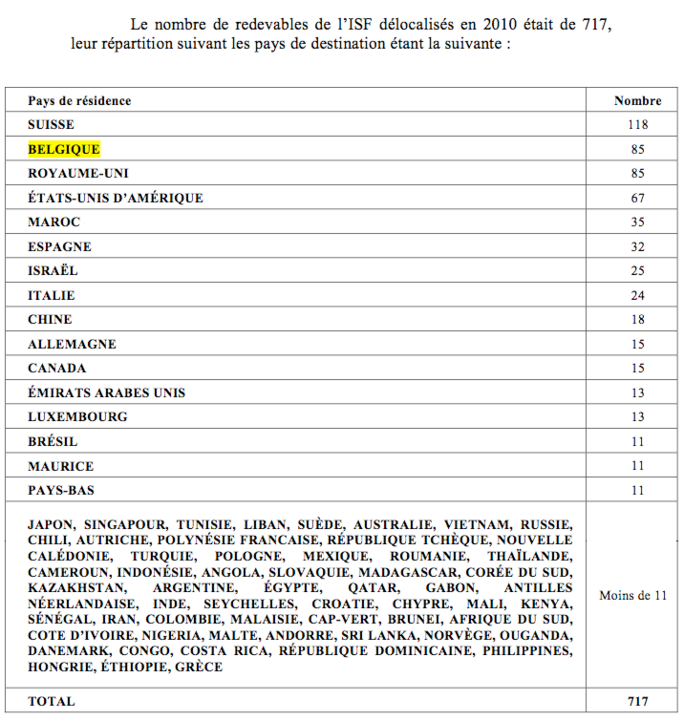

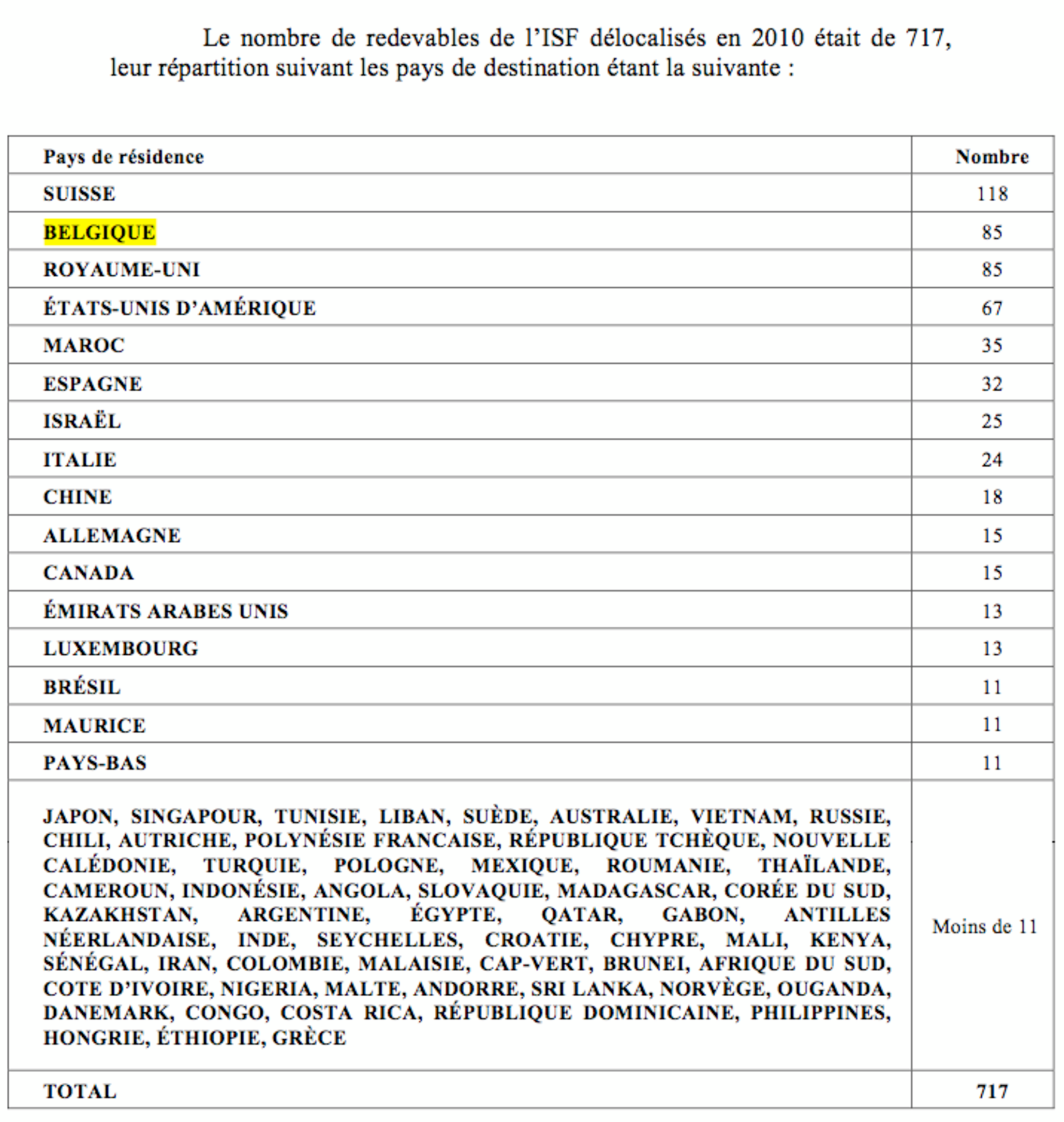

According to official French finance ministry monitoring of the expatriation of French citizens or households to whom the ISF wealth tax is applicable, those heading across the border in Belgium are a relatively modest number, and a stable one over recent years. Out of a total 717 expatriations worldwide concerning this category in 2010, there were 85 who settled in Belgium. Previously, 84 set up home in Belgium in 2009, and 89 in 2008. The ministry’s figures for 2010 show Belgium and the United Kingdom were the joint second-most favoured expatriation destinations for this category, just behind Switzerland and ahead of the United States.

The table below is a compilation of the numbers of 2010 expatriations of people and households liable to pay the ISF, based on the ministry’s information and published in a recent French Senate committee report on the flight of capital and assets from France and the effects this has on the fiscal system (available, in French only, here and here).

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Foreign investment in Belgium up 50% in 2010

Belgium offers a financially attractive alternative not only for wealthy French individuals fleeing taxes at home, but also companies.

While the vast majority of the country’s population are subject to one of the highest tax and welfare system contribution payment levels on work-related income in Europe, Belgium is comparatively lenient when it comes to taxing wealth and capital. It has no equivalent to the ISF, most property transfer operations are free of taxation, as are also profits gained from shares sales.

Inheritance tax rates vary according to the administrative region of the country where the succession is legally processed. In Brussels, the inheritance tax is around 30%, compared with the 45% inheritance tax applied across all of France.

In 2006 Belgium created a 'notional interest deduction', which is a tax deduction for the use of venture capital. In short, it encourages corporations to raise financing through equity capital, by allowing those who do so to deduct from their base tax a ‘notional’ interest charge that would have applied under normal borrowing rates. The system, which by implication involves large, financially solid corportaions, applies to every company in Belgium, which includes some 200 multinationals.

According to a study by the Belgian far-left Workers Party, this ‘notional interest’ deduction has allowed the Brussels-domiciled Belgian subsidiary of Bernard Arnault’s luxury goods company LVMH, created in 2008 and called LVMH Finance Belgique, to deduct a total of 140 million euros from its tax dues between 2008 and 2011. The study, published earlier this month, claimed that the LVMH subsidiary had in all benefited from a reduction of 188 million euros in tax payments over the same period, when including other deduction schemes.

It added that in 2010 the subsidiary, by using the various advantages of the Belgian fiscal system, paid just 11.5% on its profits, compared with Belgium’s relatively high standard tax rate on company profits of 33.99%. Contacted by French daily Le Monde, a spokesman for LVMH confirmed the subsidiary had benefited from the tax deductions, but described the cited 188 million euros saved in tax payments as “too high” while declining to offer an alternative figure.

According to a recent report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD, foreign investment in Belgium jumped 50% year-on-year in 2010, when it represented almost 62 billion dollars, prompting UNCTAD to rank it fourth-most attractive country worldwide for direct foreign investment, after The US, China and Hong Kong. As Belgian weekly De Tijd reported, that same year, French companies LVMH, EDF, Auchan, Vinci, GDF Suez , Schneider andLactalis all made a considerable increase in the capital of their Belgian subsidiaries, to the tune of several billions of euros.

“Money doesn’t like tax,” read an editorial entitled 'The hypocrites’ ball' in Belgian daily Le Soir earlier this month, “and the reason that sent thousands of Belgians running to Luxembourg is the same as that which encourages billionaires into the world’s tax havens. If Belgium created the ‘notional interests’ it is because it knows the advantage in being another [country’s] tax haven.”

Ironically, since the arrival of a socialist government in Belgium in 2011, a growing number of the country‘s wealthiest individuals, fearing an imminent rise in taxes, have begun expatriating to Switzerland. In a report by daily L’Echo published in January, an interview with a Swiss tax lawyer helping Belgians settle in the country echoed the comments, cited earlier here, of Belgian fiscal lawyers helping the French settle in Belgium. “All nationalities put together, I help about 20 to 30 people per year to delocalize,” said Swiss lawyer Philippe Kenel. “The number of Belgians virtually doubled last year.”

Others have begun settling, closer to home and within commuting distance, in Luxembourg.

The editorial in Le Soir underlined how the wide differences in tax policies among European countries sees both wealthy individuals and corporations to move, in all legality, from their own national borders to countries with more advantageous tax regimes.

No EU initiative in sight

This shopping around in legal tax avoidance costs EU states a total 150 billion euros per year in lost fiscal revenue (a sum equivalent to the Czech Republic’s gross domestic product). That was the conclusion of a report commissioned by the European Parliament’s socialist and democrat group from Richard Murphy, director of Tax Research UK, an association that exposes tax fraud and the mechanisms used in tax evasion. Meanwhile, noted the report published in February, illegal tax evasion costs EU countries an estimated 850 billion euros per year.

While the EU champions ever-greater economic integration among its member states, notably the harmonization of budgetary rules, and is now planning an EU-wide banking union, the question of tax harmonization is not on the agenda. “Wealth tax, inheritance tax and also all other direct taxes upon individuals are a matter for national governments,” commented a spokesperson for Algirdas Šemeta, EU Commissioner for taxation and customs union, audit and anti-fraud. “States are only required to uphold some fundamental principles [...] for example the respect of free circulation of people and capital as laid down in the [EU] Treaties.”

In the absence of any wide coordination on the issue, a number of individual states have bilateral agreements, which are often hazy and ineffective. Following the furor created by Bernard Arnault’s confirmation that he was applying for Belgian nationality, French finance minister Pierre Moscovici announced that he wanted to re-negotiate cross-border fiscal agreements with Belgium, Switzerland and Luxembourg “in the coming years”.

One possible move is to require French tax exiles to pay part of their taxes to the French treasury, an idea supported by both President François Hollande and his predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy in their election campaigns this year.

-------------------------

English version: Graham Tearse