Over a period of 30 years, celebrated South African photographer Santu Mofokeng has documented apartheid and its aftermath in dramatic, black-and-white stills, latterly turning his lens on many other contemporary issues. The Jeu de Paume museum in Paris is this summer hosting a world-tour retrospective exhibition of his stunning photos entitled Chasing Shadows - a reference, the photographer says, to the idea that "you can't see spirits". Clément Sénéchal reviews the powerful images on display and talks to Mofokeng about how he approaches his subjects and why he shuns fast-lane "digital bulimia".

----------------------

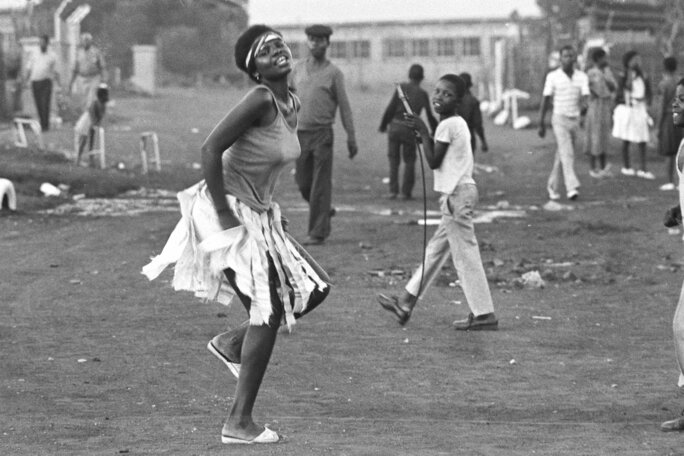

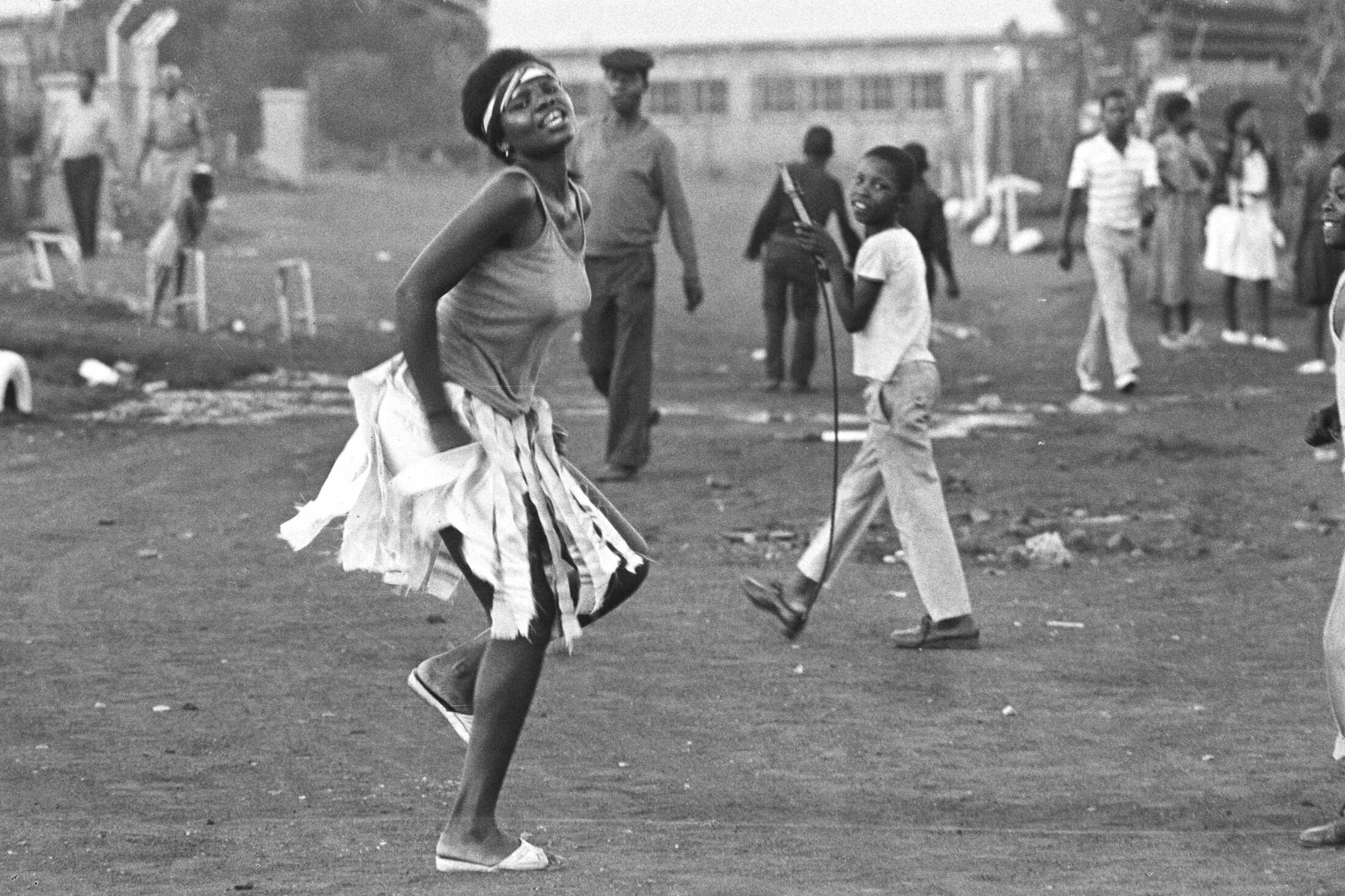

South African photographer Santu Mofokeng was born in Soweto, the renowned satellite township of Johannesburg reserved for blacks during apartheid, growing up in a place where space of all kinds - geographical, social, symbolic, temporal - was divided along racial lines.

But in a sense, Soweto gave birth to him. He began his career in the 1970s with portraits of his family and friends, capturing the details of everyday life there.

Now the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris is holding a retrospective exhibition entitled "Santu Mofokeng, le Chasseur d'Ombres" (Santu Mofokeng, Chasing Shadows, on from May 24th to September 23rd 2011.(1)

Enlargement : Illustration 1

From these beginnings with street photography Mofokeng was hired in 1981 as an assistant in the photo lab at Bleed magazine, which allowed him to refine his technique. Then, in 1985, he joined Afrapix, a collective founded in 1982 that supplied photographs documenting the struggle against apartheid. At the time his photographic reports of life in apartheid South Africa were published in alternative journals the Weekly Mail, now the Mail & Guardian, and the New Nation.

But the speed of journalism did not suit Mofokeng. While his colleagues would jump in their cars and rush their films back to the lab as soon as they had finished a job, he could not drive.

"I would take a week to do a report and I wasn't going to meet a deadline the next day," he told Mediapart (please see ‘Boîte Noire' box at bottom of page). He then began to think in terms of books rather than newspapers and magazines. "Taking my time became my strength," he added.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

This made Mofokeng start to see his work in terms of what he calls "essays", and he began several photographic series that sought to explore, almost anthropologically, the social phenomena that defined his community's place in its own time.

In the first such series, perhaps one of the most accomplished, Train Church (1985-1990), included in the Paris exhibition, Mofokeng photographed the religious ceremonies that would take place during the three-hour train journey taking workers from Soweto to Johannesburg. The journey became an end in itself, serving as a place of prayer, a temporal refuge in which a cathartic spirituality could be expressed amid the clapping of hands, the ringing of bells and the trance of singing.

For Mofokeng, the Soweto trains brought together two of the most significant aspects of that South Africa, the constant commuting and this spiritual expression. "For the black majority, the system of commuting between home and work is not the result of natural changes," he commented. Expulsions and forced relocations under the policy of so-called separate development created the phenomenon, he said. "It is the origin of the migrant worker system."

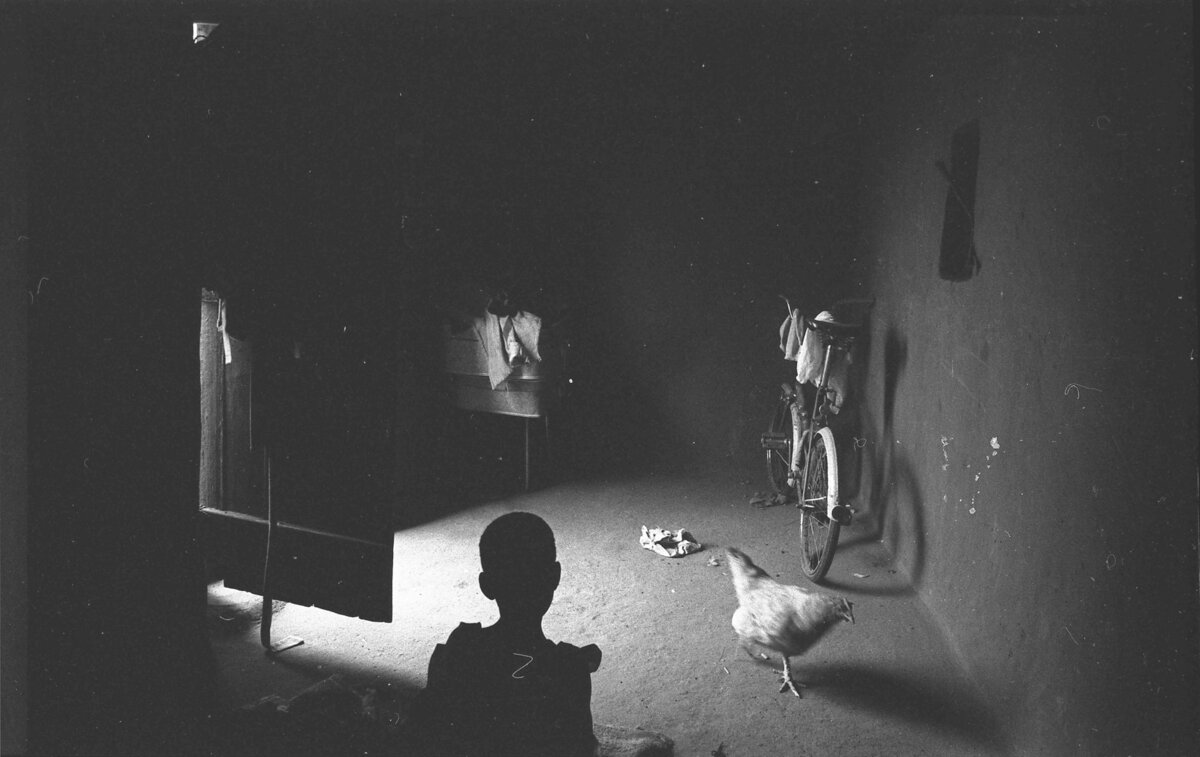

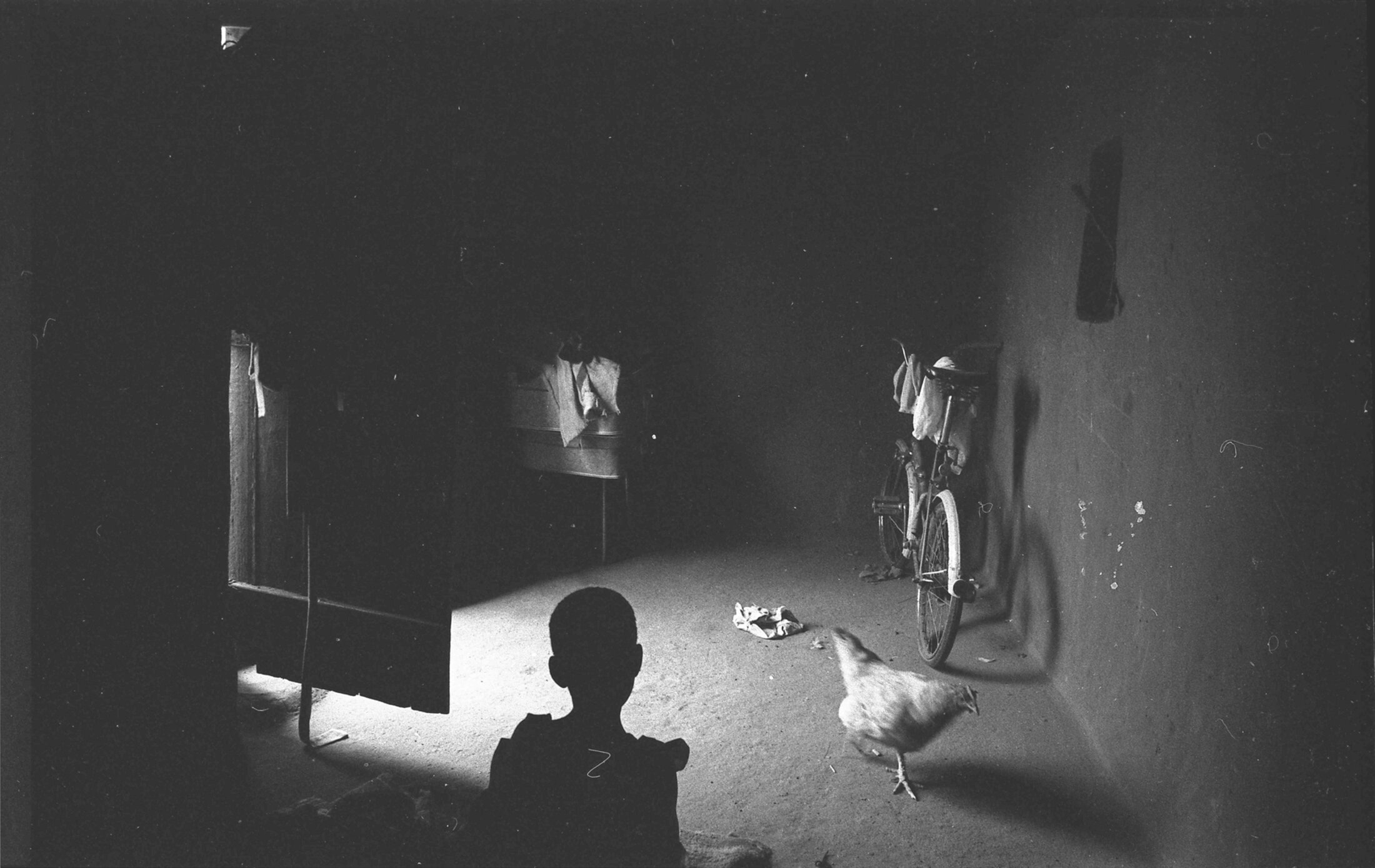

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The dramatic play of light and darkness in Mofokeng's photos gives physical form to this mythical ecstasy which brightens and lightens the journey. He touches and reveals a deeply moving moment of intimacy

-------------------------

1: The exhibition will continue at Kunsthalle Bern (7 October - 27 November 2011), Bergen Kunsthall (23 January - 26 February 2012), Extra City Kunsthal Antwerpen (March - May 2012) and Wits Art Museum Johannesburg (September 2012).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Mofokeng's interest in the use of space continued with the series Appropriated Spaces, which explores how, through what rituals, South African blacks were able to breathe some life and social animation into such precarious places. There again, religious expression was important.

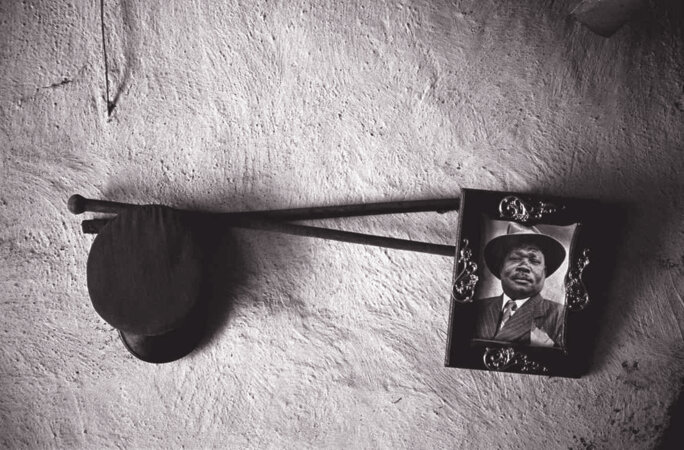

A few years later, in 1988, he began Rumours/The Bloemhof Portfolio, focusing on the tenant farmers and agricultural workers in Bloemhof, a small town on the banks of the River Vaal. This allowed him to question rural apartheid.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Mofokeng's work during the apartheid years shows untamed, full lives in all their precarious resistance. But the work he would produce after apartheid was abolished in 1991 reflects a feel of desuetude, disillusion.

The series Township Billboards: Beauty, Sex and Cellphones captures the way billboards are spread around in the townships, icons of an emerging medium for communication between the leaders of the country and its inhabitants. The transitional state of ideology, the social and economic climate and the country's politics is palpable here.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Here Mofokeng's art becomes tinged with a touch of bitterness, he becomes somewhat distant, viewing things as a stranger might.

He moved on to two series, Trauma Landscapes and Landscape and Memory, in which he turns towards memory, the trace left by history in landscapes that have gradually been covered over by the passage of time. Struggling with a string of questions - how to portray mass graves and concentration camps, whether a monument invites remembering or, by confining the event, forgetting, who owns these memories, and how one can face places which are associated with negative or traumatic memories - he photographed the vestigial remains of concentration camps.

He also turned his lens on village houses where children had become heads of their families after their parents died of AIDS, in a series entitled Child-Headed Households. Until recently, prevention campaigns were more prevalent - and antiretroviral drugs more available - in rural villages rather than in the urban environment of the townships.

Often, death certificates in these rural communities imbued with religious traditions would give the cause of death as "natural causes". Mofokeng transcribes the mind-boggling reorganisation that takes place in such homes and surprises the symbolic points of friction that must happen of necessity.

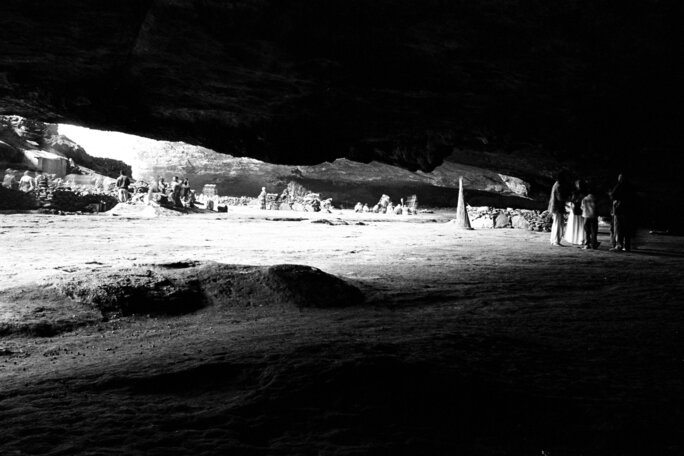

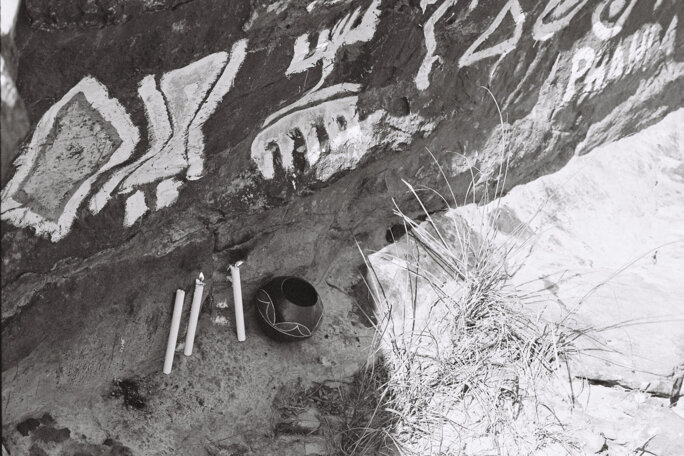

He pursues variations on illness, AIDS in particular, with Chasing Shadows, a series that shows the superstitious pilgrimage made by numerous AIDS sufferers to Motouleng, a cave where they seek both moral and physiological redemption.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

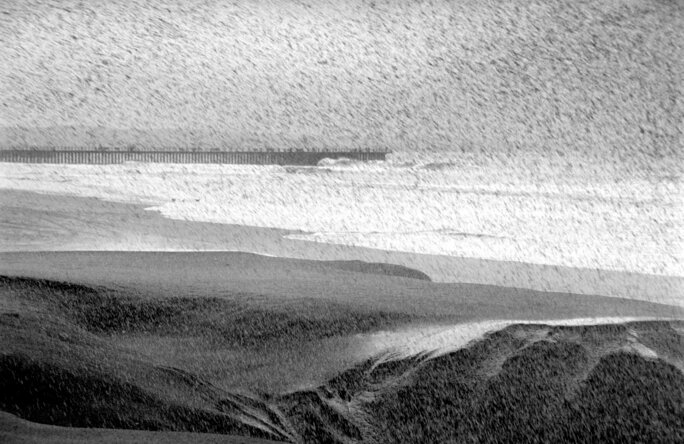

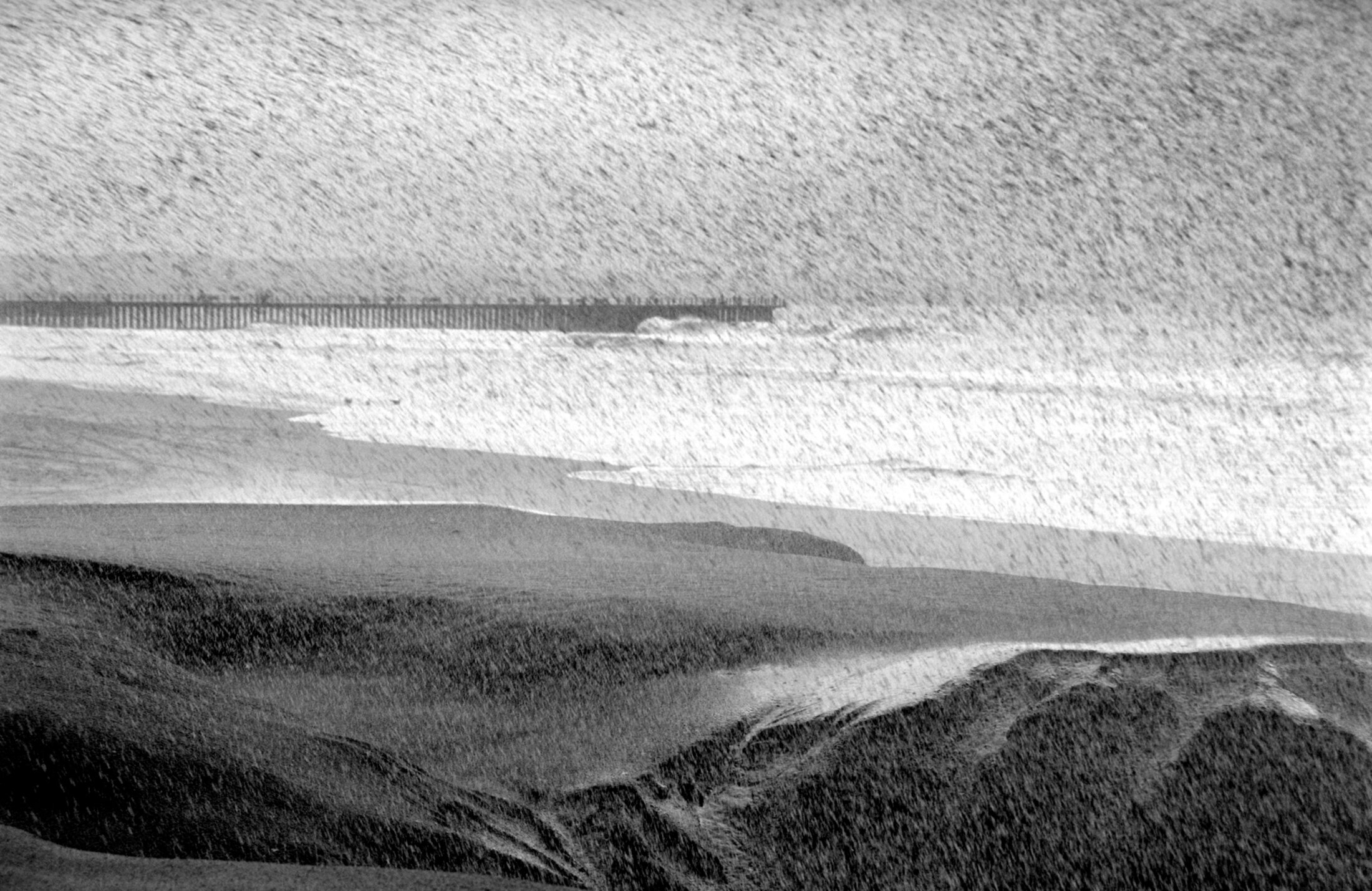

Finally, in Radiant Landscape, a photographic essay Mofokeng did for the exhibition itself, he looks at how pollution deforms the landscape. Poisoned human and geographical bodies suffer an inevitable metamorphosis in the form of gradual acid deposits.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

In an interview with Mediapart, conducted while he was in Paris for the opening of the exhibition (please see ‘Boîte Noire' box bottom of page), Mofokeng began by answering the question of whether he sees himself as a reporter, or a militant or an artist.

Santu Mofokeng: Those three dynamics do probably exist in me, in what I am as a person. But when I think about my photographic work, I think first of all about being artistic.

I am not sure that pictures can change the world and, as I get older, I have been led to bring a little more distance and complexity to my subjects, to remain aware of the irreducible ambivalence around them. To me this concern with ambivalence is more characteristic of an artistic approach than a militant approach, even if, obviously, political struggle and commitment are part of who I am.

Mediapart: How do you choose your themes?

S.M.: I don't feel as if I do choose them. I think it's more the subjects that choose me when I pass by them. I don't work under pressure. I let myself be guided by my intuition more than working concepts out in advance. That means each essay takes on a biographical dimension, they are different aspects of the whole that constitutes my life.

My intention is to communicate the metaphysical chapters of my existence. My art is a visual narration. Photographers are often in a hurry, they are looking to anticipate events. I'm not interested in the event. The reality always remains, and I take whatever time is needed to find it and embrace it visually in a holistic way.

Mediapart: You take your time when you work, you seem to be anchored in the approach to a subject, yet the photographic moment is by definition instantaneous. How do you reconcile these two aspects?

S.M.: That depends on what you mean by instantaneous. Obviously you can describe photography as the art of the click, time is cut into slices by the camera. But a lot happens before the shutter opens. First of all the photographer needs to understand the space around him, what is happening in front of him, before there can be a click, first of all in his head, and then in a technical way in the camera.

In my pictures I think the instant is improved by an expansion of time, by stretching it out so as to record in a different way from that which has come from all this digital bulimia. The meticulous process of development in a dark room is also what constitutes a good picture.

I like the ambivalence of the picture. But in the decisive moment, when it is as if what is evident imposes an interpretation on us, this ambivalence is extinguished and you are left with something cruder.

Mediapart: You mentioned digital photography, which has changed how photography is practiced in society. How do you use it?

S.M.: I use it as a notebook. Digital allows you to take a lot of shots, which undeniably gives it a practical side. So I use it for scouting, but I always take the final photo in [analogue]film. For the moment I am experimenting, but it remains secondary in the way I work. Perhaps later on. I like to be in control and I do not want to be submerged by technology. Sometimes all the new possibilities suffocate you.

Mediapart: What is the place of professionals in a society where photography is increasingly done by amateurs?

S.M.: There is a saying which goes ‘Take a stone and throw it into a crowd, you are sure to hit a photographer'. I think there is still a need for professional photographers. What makes the difference is in the eye. You develop an eye, you educate it. I worked in a dark room for five years. That's how long it takes to get a diploma, a Master's. Do children or amateurs still have the patience for such learning at this time of new technologies? No.

And perhaps I myself am also too old to relearn, to take a completely different path. I like to have complete control, right from the dark room to the arrangement of the exhibition. Film is part of this chain.

Mediapart: You present your pictures with a lot of writing, verbal explanations. Wouldn't they be clear enough on their own?

S.M.: The writing that goes with my photos is not there to give an interpretation. It is not there to explain. I got into this habit at the time when conservatives and progressives were confronting each other in South Africa, when every single thing was manipulated for political ends, and especially pictures, which have immense power in the media.

Perhaps it is an excessive control that is damaging for the artistic liberty forged between the work and the viewer, but I do not want people to take my pictures too far from their initial intention. The writing is a neutral indication, usually documentary. You do need to be able to recognise things, the place, the time, the people, and so on.

Mediapart: Spirituality is one of the main themes of your work. Are you a believer?

SM: For me spirituality is not so much a question of belief as of a climate, a presence. It is the atmosphere in which I grew up which permeated everyday life for my ancestors, my family. It was their way of way of being in the world. Politically, you could wonder if this faith helped them to support each other in life despite apartheid. Where I come from, spirituality makes people act, it pushes people. It's a system of incentives doesn't seem any less worthy than the ones you have in the West.

-------------------------

- See more of Santu Mofokeng's work Page 4.

English version: Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)

Portfolio

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Enlargement : Illustration 10

Enlargement : Illustration 11

Enlargement : Illustration 12

Enlargement : Illustration 13

Enlargement : Illustration 14

Enlargement : Illustration 15

Enlargement : Illustration 16

Enlargement : Illustration 17

Enlargement : Illustration 18

Enlargement : Illustration 19

Enlargement : Illustration 20

-------------

"Santu Mofokeng, le Chasseur d'Ombres" (Santu Mofokeng, Chasing Shadows, is open from May 24th to September 23rd 2011 at the Jeu de Paume, 1, place de la Concorde in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. Nearest Metro sttation: Concorde.