On Friday the French arm of Swiss bank UBS was placed under formal investigation by judges undertaking a wide-ranging probe into allegations that it has enabled wealthy French nationals to evade paying tax in France on sums deposited in undeclared Swiss bank accounts. Two Paris-based investigating magistrates, Guillaume Daïeff and Serge Tournaire, are examining claims of “laundering the proceeds of tax fraud” as well as the unauthorised direct selling of products. UBS France was put under investigation – one step short of charges being brought – in relation to the illicit selling of products to wealthy French clients. The bank was named as an “assisted witness” in relation to the laundering of proceeds of illicit selling and of the proceeds of tax fraud. This is a status that could be changed to being placed under investigation if new evidence comes to light in the inquiry. Here Mediapart reports on new evidence which suggests that, contrary to the bank's claims that any unlawful activities were carried out by a few individuals, an organised parallel accounting system existed to record the opening of undeclared accounts. Dan Israel reports.

-----------------------------------

A number of senior figures at the French arm of Swiss bank UBS oversaw an organised system that allowed wealthy French nationals to cheat the taxman by stashing their money in undeclared Swiss bank accounts, according to previously unseen documents and corroborating witness statements examined by Mediapart. This starkly contradicts claims made by the bank's French subsidiary that any wrongdoing was simply down to a few rogue individuals.

The allegedly organised system of tax evasion targeted wealthy French families, celebrities and well-off business personnel across France. It was apparently run by staff of the bank in both France and Switzerland.

The system centred around the use of what were known at UBS as 'carnets du lait', literally 'milk books' or milk records. Traditionally used by Swiss farmers to record how much milk they sent to the dairy, the practice of keeping 'milk books' was adopted by the Swiss financial sector, including by staff at UBS. The bank says the notebooks were simply used to record new business and share out the financial rewards arising from it. But the allegation is that these books in fact formed part of a secret, parallel, handwritten accounting system used by some senior figures in the bank from 2004 to at least 2008 to record the opening of undeclared bank accounts by French clients in Switzerland, and to carve up the resulting bonuses between client managers.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The use of these notebooks and the alleged tax evasion system they concealed have been publicly revealed since 2008 by a number of bank staff, all of whom have subsequently been removed or sacked. The books now form a key line of inquiry for the two Paris-based examining magistrates, Guillaume Daïeff and Serge Tournaire, who since April 2012 have been investigating allegations of “peddling of banking or financial products by unauthorised personnel and the organised laundering of the proceeds of tax fraud and of funds obtained with the help of unlawful peddling” in relation to the bank. Specifically, the claim is that Swiss bank staff were unlawfully canvassing potential clients in France, whose money was then placed in undeclared Swiss bank accounts.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The bank itself denies that the “milk books” were used for anything other than legal practices. Questioned by Mediapart the current president of UBS France Jean-Frédéric de Leusse, who was appointed in March 2012 and who was questioned last month by the two judges investigating the affair, gave his version of the facts. “Inside the UBS group there is a procedure to identify new business brought in; when a banker indicates that they have brought in new business to one of his colleagues, for example in Switzerland, England or in another office in France we can, according to the contribution they've made, apportion 50% or 100% of the business to one or the other,” says de Leusse.

“In our jargon they're called ATAs [editor's note, standing for assets transfer adjustments],” says the banker. “From 2004 to 2008 the person managing the bank's affairs in France asked all those in charge of [regional] offices to pass through him, on a continuous basis, what [business] they had said they had done with other UBS offices, via an internal management document called a 'milk book'.” According to the UBS boss these books were in the form of simple Excel spreadsheets “summarising the 'business' carried out under his monitoring and allowing him, through the course of the year, to check the activity of the bankers”.

Critical report from banking watchdog

Three former executives of the bank are also currently under formal investigation. They are Patrick de Fayet, the former director general and head of wealth management; Hervé D’Halluin, who ran the bank's operations in Lille in northern France and Laurent Lorentz who was in charge in Strasbourg in the north-east of the country. Two other executives, Anne Longin, head of the bank's Paris operation and Étienne de Timary, regional director at Lyon in eastern France, were taken into custody for questioning on Tuesday 21st May and released the following evening. An internal UBS message dated 23rd May welcomed the fact that the two executives had not been placed under formal investigation, though that is still possible at a later date if they are called before the examining magistrates.

The legal aspect of the UBS France affair began in March 2011 when the Paris prosecution service launched a preliminary investigation – which was broadened the next month into a full judicial probe - after being alerted by the banking supervisory body the Autorité de contrôle prudentiel (ACP). This watchdog had received an anonymous but very detailed note outlining the bank's activities between 2002 and 2007. According to Mediapart's information, the ACP is still involved in the case. One of its inspectors carried out an investigation of UBS from December 2010 to April 2011 and delivered their report on 21st December 2011.

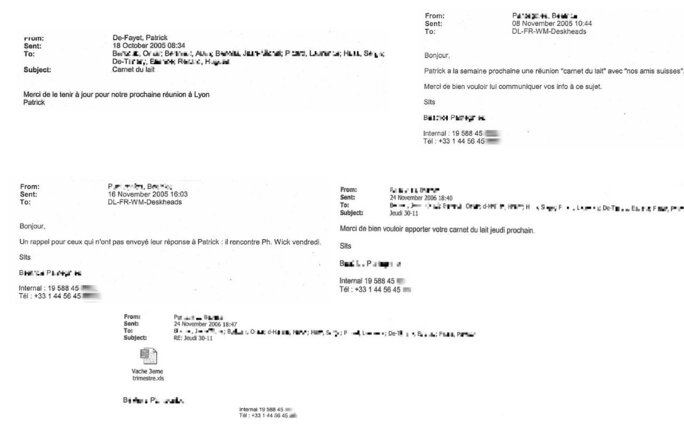

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The findings are devastating. A summary of the report's conclusions notes in particular that “UBS France and the group it belongs to have not implemented the means necessary to establish” if the accusations of its former staff were well-founded, and underlines that the work of the inspection operation “does not allow [one to] give credence to the establishment’s explanations” over the “milk books”. In the coming weeks the bank might be summoned before the ACP's sanctions committee, which could end up costing it dear. The committee has the power to remove a bank's licence to operate or forbid one of its executives from working in banking and can levy fines of up to 100 million euros.

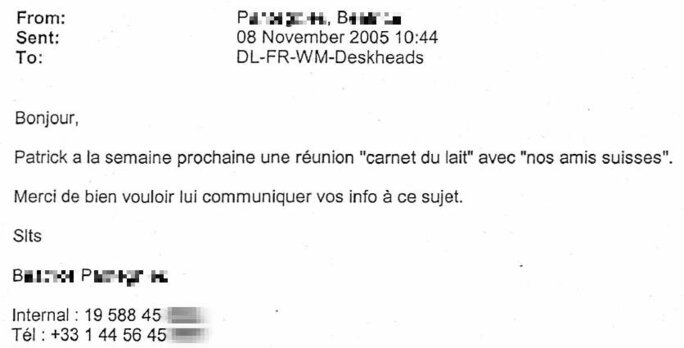

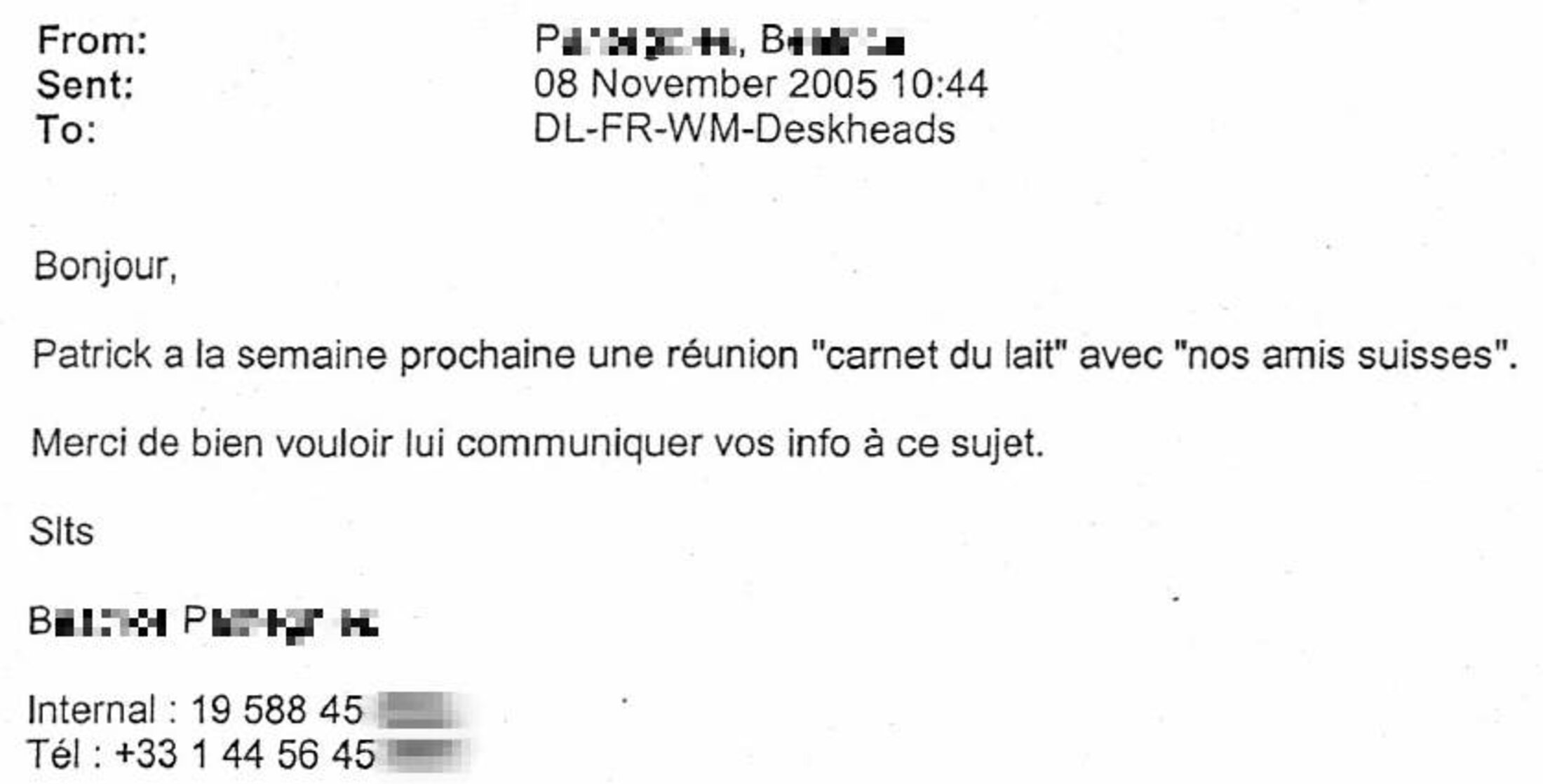

Witness statements obtained by Mediapart meanwhile contradict the bank's suggestion that the milk book system was used for entirely legal ends. “Very regularly, and at least every quarter, emails and SMS messages were sent to the heads of the regional offices by their superior Patrick de Fayet or his secretary Béatrice P.,” says one former executive. “They were to do with filling in the Excel files called 'Vache' [editor's note, 'cow'] which recorded the sums of money collected from French clients to be sent to Switzerland. The procedure changed regularly, and sometimes the instructions were only sent orally, but at least one regional manager protested, saying he preferred a written trace.”

The tone of the messages calling for the “milk books” to be filled in was pithy and quite mysterious. Though the existence of such messages has been mentioned in media reports, as far as Mediapart is aware their content has not been published before. For example there was a message sent on October 18th 2005 directly by Patrick de Fayet to the heads of the offices in Cannes, Marseille, Bordeaux, Nantes, Strasbourg and Lyon, as well as to the person responsible for UBS clients who had stock options. The subject was: “carnet du lait”. The message was: “Please keep them up to date for our next meeting at Lyon. Patrick.” The following reminder, which came three weeks later, talked about “Swiss friends”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

So who were the “Swiss friends”? De Fayet's secretary gives a clue in an email later that year on 16th November when she mentions “Ph. Wick”, referring to Philippe Wick. Based in Geneva, Wick was, until he resigned in April 2008, one of those in charge of the 'France International' department at UBS in Switzerland. This managed the French assets held in Swiss coffers. This money was, for the most part, not declared to the tax authorities in France.

If some middle managers at the bank are to believed, the fact that money collected in France sometimes found its way discreetly across the frontier into Switzerland was hardly a secret. “The milk books were used to keep track of this money and to share out the bonuses between chums,” says someone with a good knowledge of the affair. “It was obvious to everyone. For example, sometimes the head of a French branch [of the bank] officially received a bigger bonus than others yet he and his team had declared – also officially – that they were managing lesser sums than their colleagues elsewhere in France.” Other former staff insist that the “milk books” could also have recorded legal transactions.

'They take us for idiots'

Enlargement : Illustration 5

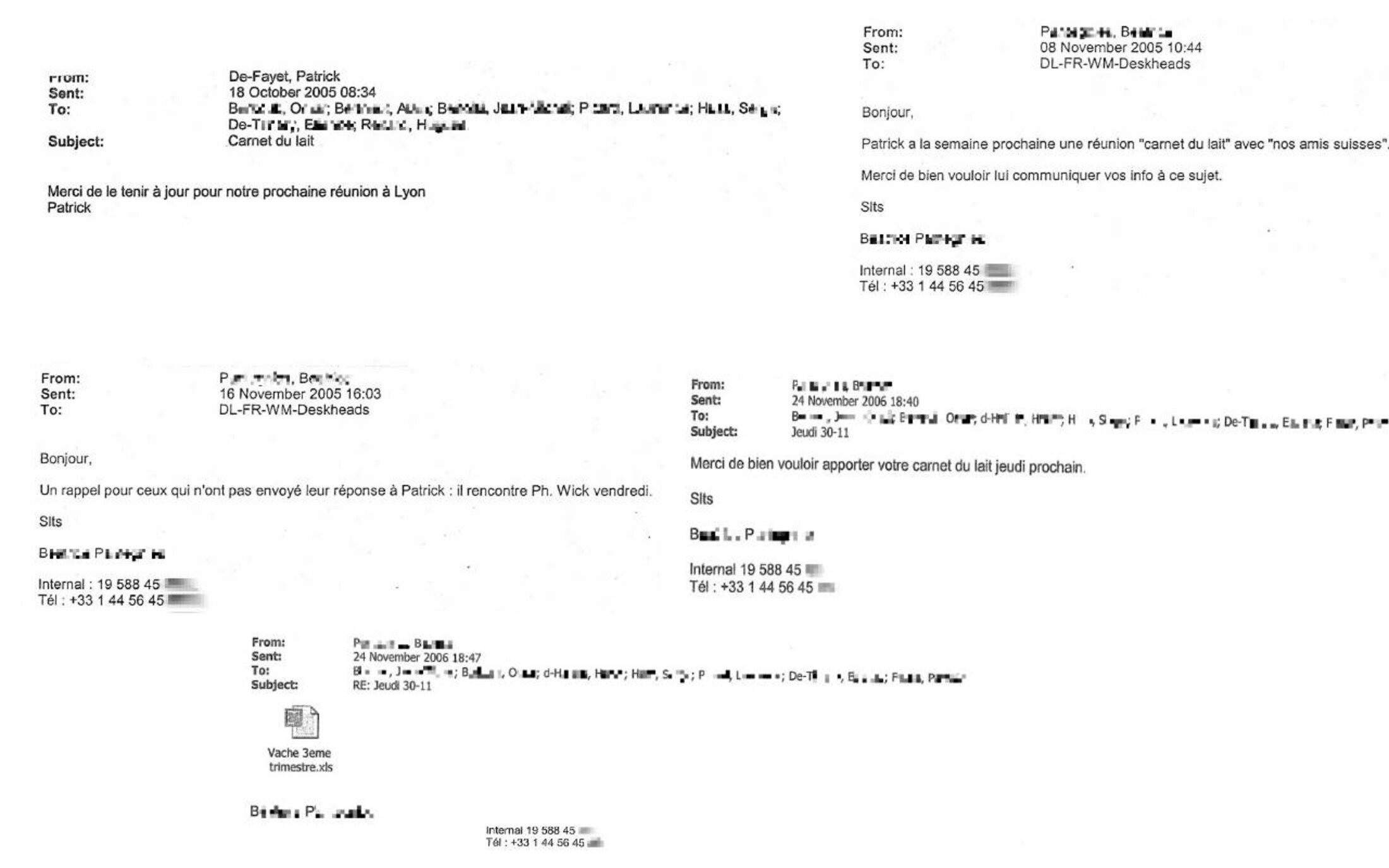

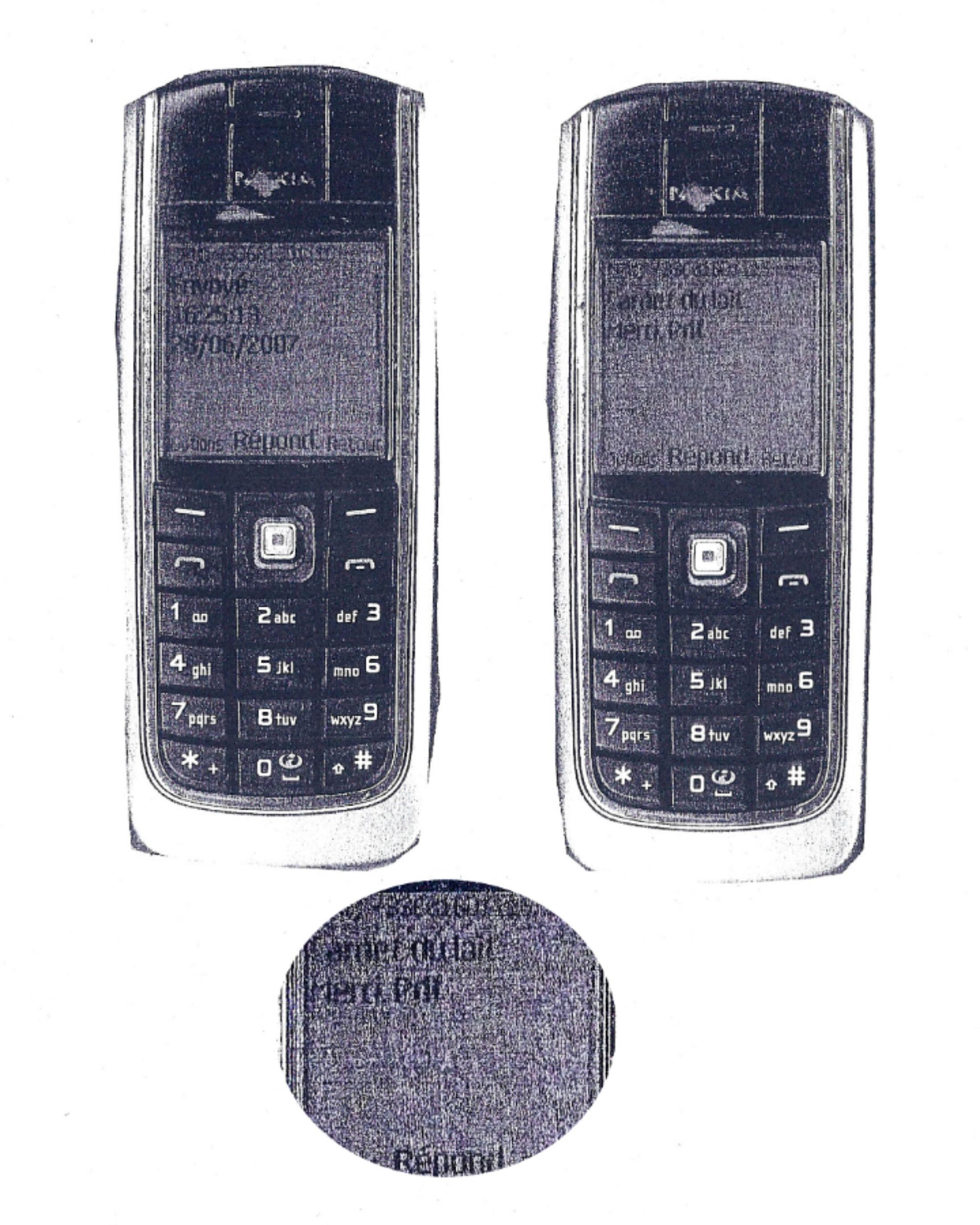

The 'Vache' files used to record business contained boxes in which the user had to provide the name of the client manager, the name of the client, the amount involved in the transaction and the date. This detail was included in an email sent by Béatrice P. dated 24th November 2006. Mediapart also has a copy – which is difficult to read (see right) – of a printout of a pithy SMS message which was apparently sent from Béatrice P.'s phone on 28th June 2007. It said: “Milk book. Thank you. Pdf.” [Editor's note, Patrick de Fayet's initials are pdf.]

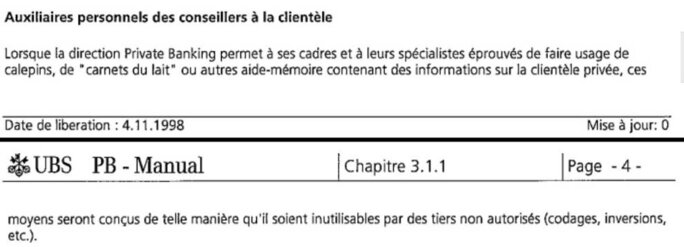

As already mentioned, such terminology was common in certain Swiss banking circles and was introduced to France in 2003 or 2004 by a Swiss employee of UBS. The term “milk book” is even mentioned in passing in the bank's internal document the 'Manual of Private Banking' which outlines all the rules and regulations to be followed by staff. In Chapter 3 of the manual (see below), devoted to conducting business relations and with an emphasis on banking confidentiality, the “milk books” are described as a kind of aide-mémoire that can be put at the disposal of executives or “dependable specialists” in client relations, and which need to be encrypted if they are used in electronic format.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Does this mean that the use made of these notebooks was perfectly legal? The official line at the bank is that it has always been resolute in flushing out the least suspicion of illegal activity. Yet according to witnesses, staff have always understood that the lines they were not supposed to cross were moveable. “To [open an undeclared account] was never presented as the main aim,” says a former employee. “But given the very high targets that were set, each person understood that he was free to bring in and declare in the books something other than declared money. And in practice one was led to understand that this route was entirely practicable, even desirable.”

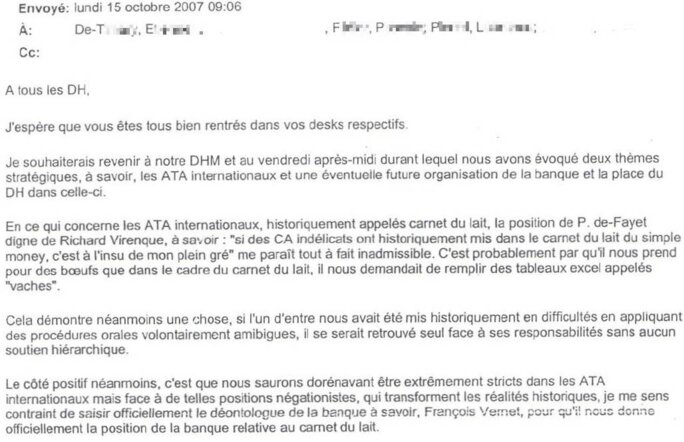

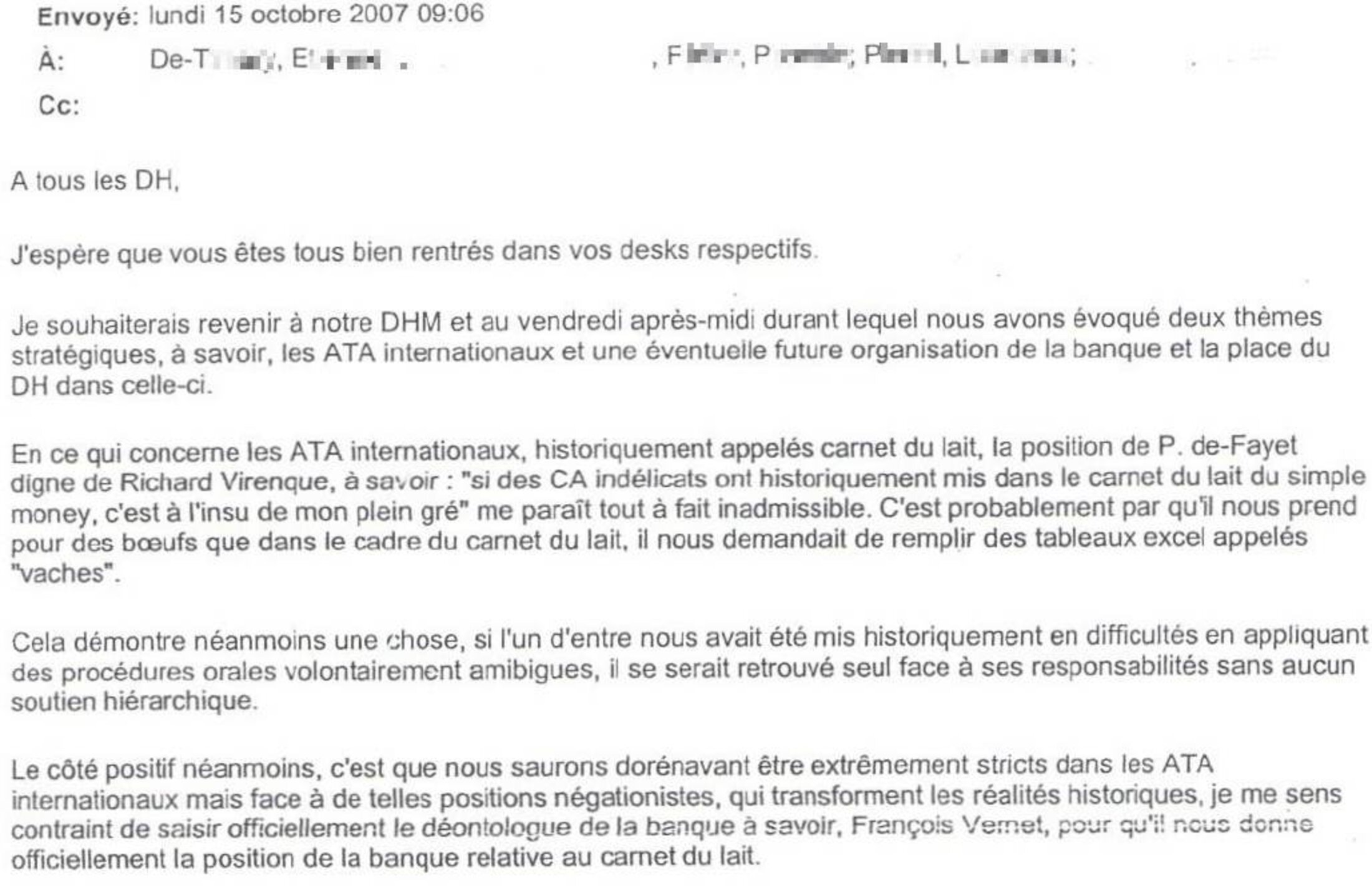

This apparently ambiguous position on the part of the bank's management did not please everyone inside the financial organisation, as revealed by an email whose contents were recently published by Le Croix newspaper. It is dated 15th October 2007 and sent by one of the French regional directors to his counterparts around the country. The email (see below) refers to a “DHM” or desk heads meeting that had taken place three days earlier in the presence of Patrick de Fayet. The writer lets it be known in ironic but trenchant terms that he was not happy about the way the issue of “International ATAs, historically known as milk books” had been tackled.

The author of the email says “P. de Fayet's position” is “worthy of Richard Virenque (1)” and “absolutely unacceptable”. He then summarises what he sees as his boss's defence: “If some dishonest [client managers] have historically put in the milk book simple money [editor's note, undeclared money placed in offshore accounts, as opposed to 'complex' money that is subject to a series of regulatory steps] it's without me knowing about it (2).”

According to this account, therefore, the director general had made out that he did not know or did not want to know how his troops were using the milk books. The angry executive who wrote the email adds: “It's probably because he thinks we're bovinely stupid that in the milk books he asks us to fill in the Excel spreadsheets called 'cows'.”

Enlargement : Illustration 7

The regional director was also worried about legal repercussions. “If, historically, one of us got into difficulty by applying deliberately obscure oral procedures, they'd find themselves alone when facing up to what they've done, with absolutely no support from above,” he wrote in the 2007 email. Five years on and his fears proved justified, as the bank did not defend the two former regional directors when they were placed under formal examination. The bank's position has not changed, as its French boss has spoken several times of “individual faults” for which his organisation is not responsible.

This stance must come as a disappointment to Hervé d'Halluin, the former regional director at Lille who is now under formal investigation. On 27 May 2010 he gave witness evidence at an industrial tribunal at which his former colleague in Strasbourg was fighting his dismissal for serious misconduct in 2008. The executive from Strasbourg said he had been sacked after protesting about illegal practices at the bank, and won his case. At the hearing Hervé d'Halluin said: “I'm not happy to be here. I'm doing it out of loyalty to a former colleague.” He insisted at the time he had “no conflict” and harboured no “bitterness” towards the bank, which he had left in 2009 after the Lille office closed.

-------------------------------------

1. Richard Virenque was a popular French cyclist who then became involved in a doping scandal. He became infamous and was widely satirised for his continuing refusal to accept he had taken performance-enhancing drugs in the face of overwhelming evidence.

2. The French expression used “c'est à l'insu de mon plein gré”was the odd phrase used by Richard Virenque to try to suggest that while he did take drugs, he somehow didn't know he did. Literally it means “It's without my own free will knowing about it”. This much-mocked phrase has now entered the French language. The email author here is clearly suggesting that, in his view, Patrick de Fayet did know about the allegedly illegal use of the milk books.

'Accomplices to tax fraud'

At the tribunal D'Halluin refused to say if he considered the milk book practices to be “unlawful”, but did confirm that they went on. “Yes, I was aware of the practice of transferring undeclared funds,” he said. He added: “There were meetings where it was declared that the milk book involved unlawful transactions.”

On the same day of the tribunal the regional director of the Bordeaux office gave similar evidence. He said he had taken part in “some meetings where the transfer of funds without a declaration [editor's note, to the French tax authorities] had been mentioned” and stated that “the milk book did not involve lawful transactions”. According to him, not only did Patrick de Fayet approve of the use of the milk books, the head of the French institution's legal department from 2004 to 2009 François Vernet also “knew about the unlawful transactions” which, however, he apparently tried to oppose.

Vernet's predecessor as legal director Éric Dupuy was also aware of the transactions. As first FRANCE 24 then Le Croix revealed, he was very animated on the subject during a preliminary meeting held on 6th February 2004 to discuss his dismissal. Those present at the meeting were Béatrice Lorin-Guérin, the director of human resources at the bank who is still in the same post today, the president of UBS France at the time Jean-Louis de Montesquiou, and the staff member helping Dupuy during the dismissal procedure, Stéphanie Gibaud. Gibaud, who was then head of marketing, is today herself in dispute with the bank having accused it of unlawful practices and then being dismissed.

According to information gleaned by Mediapart, Dupuy was criticised in particular for not having spotted suspect transfers of funds in the accounts of some staff who had brought in new business to the bank in 2003. Each of the 14 pages of the formal account of Dupuy's interview, which Mediapart has seen, was initialled by those present. In it the legal director insists that he had obtained “new proof of the active canvassing of French prospective buyers, in France, by some teams of client managers from UBS Swiss: unlawful canvassing, plus the sale of financial products that were not authorised to be sold in France”.

Dubuy accused the bank and its top executives of becoming “accomplices to tax fraud transactions, which therefore comes under the criminal offence of laundering”. Those present at the meeting had no response for the man they were preparing to dismiss. It remains to be seen whether the examining magistrates will prove him right.

----------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter