The upper echelons of the French state knew within hours what had caused the death of botany student Rémi Fraisse at an eco-protest in the early hours of October 26th but concealed the truth for up to two days, Mediapart can reveal. Preliminary details of the judicial investigation into the death at Sivens dam in south-west France, of which Mediapart has been made aware, have revealed that gendarmes using night-vision binoculars saw the 21-year-old fall to the ground immediately after an 'offensive' grenade had been thrown at a group of four or five young protesters.

A group of gendarmes then set out, at around 2am, to retrieve the student and by 4am a preliminary examination of his body had been carried out at the nearby town of Albi, which showed that he had been killed as the result of an explosion. Meanwhile the circumstances of Rémi Fraisse's death had already been passed up the chain of command from the gendarmes on the front line to their commanding officer on the spot, with the local prefect, prosecutor and responsible ministers – for justice and the interior – then duly informed. Yet despite senior figures in the state having been made aware of virtually all the salient facts of the tragedy on Sunday morning, ministers chose either to feign ignorance or downplay the incident for two days.

That Sunday evening interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve gave a brief non-committal statement on the death in which spoke about the “violent context” in which it had occurred. Then on Monday evening the interior minister made another statement in which he spoke of his thoughts for the dead man's family but also attacked the “unacceptable violence” of some of the protesters. On neither occasion was the cause of Rémi Fraisse's death mentioned, even though by then the authorities had a fairly clear picture of events immediately before and after he was killed.

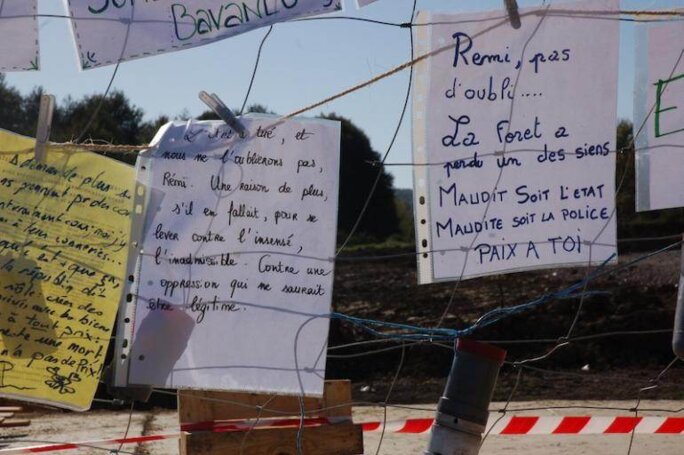

Concern over the government’s silence was spelled out by the family of Rémi Fraisse himself in a moving statement read by their lawyer Arié Alimi on Thursday afternoon. “Given that the [gendarmes] expressly saw him fall following the grenade's explosion, and that the circumstances of his death were known from that moment, why was the truth about the death of our child and brother not immediately revealed?” they asked. And the family made a “formal” appeal to President François Hollande himself to “shed all possible light” on the events leading up to the drama. They said they needed answers “to allow us to bury our son and brother knowing the truth, to be able to start our grieving and so that such a tragedy can never happen again”.

The president, who was asked about the family's request just a few hours later during a live television interview, promised that “the full truth will come out” and that he would as head of state “draw the conclusions in terms of responsibility”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Other key questions also remain to be answered over the tragedy. For example, why were gendarmes at the site at all, and why did the prefect for the Tarn département or county, Thierry Gentilhomme, call for “extreme firmness” in the handling of the protest? Lawyer Arié Alimi said the family wanted to know why the officers were there “in such numbers and so well-armed faced with a peaceful gathering in which Rémi took part and given that there was no property or people to protect that evening”.

According to evidence Mediapart has gleaned from the investigation, on the Saturday morning before the tragedy there was a meeting of gendarmes at nearby Gaillac at which it was agreed to set up “living quarters” on the Sivens site and to “hold the position”. This was despite the fact that all the heavy machinery had been removed from the site and that all that remained was a work hut and a generator, which had in fact been set alight the evening before.

The findings of the investigation so far are that Saturday itself was relatively quiet, apart from some incidents in mid-afternoon, and that the CRS riot police who had come to help gendarmes were withdrawn in the evening, at around 6.30pm. The inquiry says that the worst clashes only began at around 1am on Sunday when the gendarmes came under attack from Molotov cocktails, stones and flares. It was at this point that Rémi Fraisse, who had been with friends elsewhere on the site, went to see what was going on. It is not yet known whether he threw stones, mud - or nothing at all.

In any case, the gendarmes were not in any great apparent danger. Not only were they extremely well-protected by their equipment, they were also inside a compound with a fence and water-filled ditch separating them from the protesters. It seems likely that they could have held their position for hours without suffering any harm. Especially as, according to several witnesses, the protesters were short of flares and Molotov cocktails.

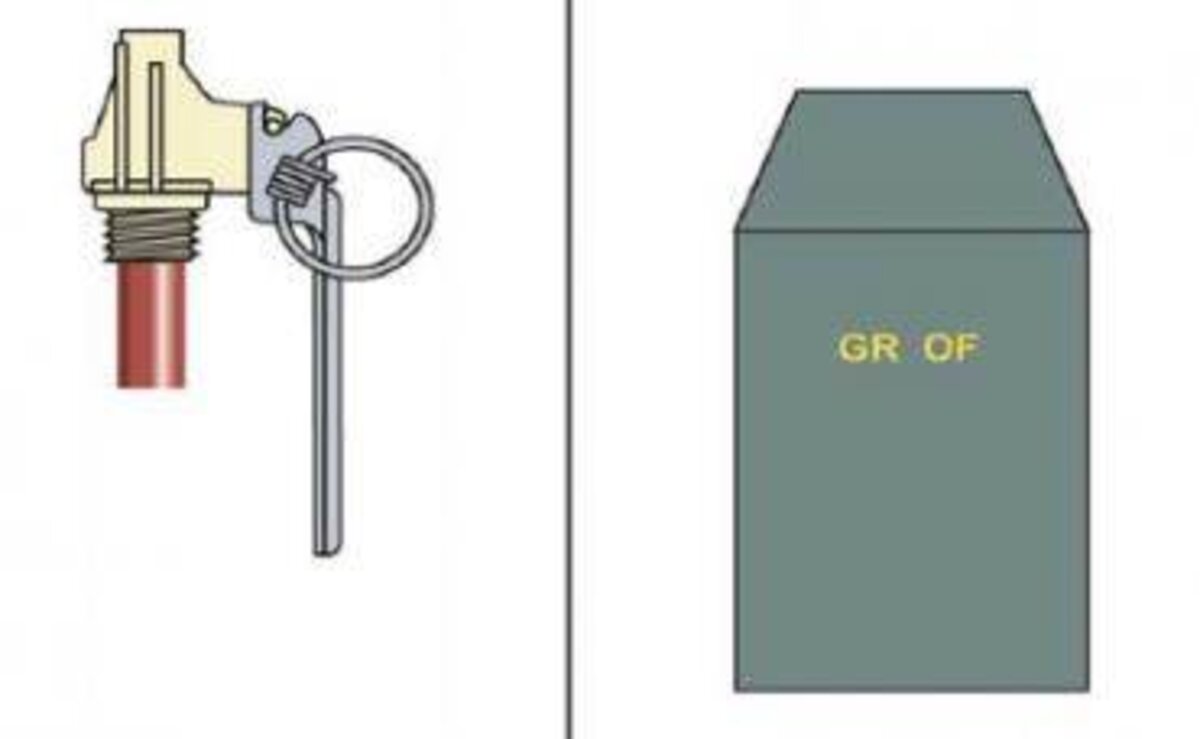

So why were around 400 grenades thrown or fired during the night, including 40 of the type OF F1 'offensive' grenades? Most gendarmes have never used these grenades, which are effectively wartime weapons, which can only be used in certain restricted circumstances and which even then should only be thrown on the ground.

Yet Mediapart has learned from sources that the officer, known only as “J”, who tossed the grenade at the four or five youths including Rémi Fraisse, some of whom were throwing stones or mud, threw the weapon in the air. Did he lose his nerve? According to his witness statement, the non-commissioned officer, who shouted “grenade!” as he threw it to warn his colleagues, says it was his own decision to toss the grenade. He did so, he says, because of the intensity of the clashes at the time. His commanding officer, the head of the 28/2 mobile gendarme squadron - EGM or escadron de gendarmes mobiles – from the Gironde département gives a slightly different account in which he claims he himself gave the order to throw it. In any case, as the family ask in their statement: “Why did these [gendarmes] deliberately throw a grenade containing exclusively explosives … in the direction of our child and brother?”

'Death consistent with a blast from an explosion'

Once the gendarmes had seen through their night-vision binoculars what had happened they turned on their projector lights, sent out a team of officers and recovered Rémi Fraisse's body. Photos were taken of his wounds as part of the initial examination of his body at Albi.

Later the two doctors who carried out a fuller examination of the student's body came to a cautious but very clear conclusion. “The death of Monsieur Rémi Fraisse is consistent with a blast injury in regard to the upper back region following an explosion.”

In their seven-page report, dated October 27th, the two doctors, Professor Norbert Telmon and doctor Frédéric Savall from the CHU teaching hospital at Toulouse in south-west France, detail the fatal injuries caused by the offensive grenade thrown by the gendarme.

In the upper part of Rémi Fraisse's back they note “a substantial loss of matter 16cm by 8cm, almost horizontal in position, reaching the chest cavity, which presents at its lower extremity multiple lacerations 3.5cm long”. The experts also record a “laceration of the upper lobe of the left lung and a crushing of the rear section of the upper thoracic region, involving the shoulder blades, the rear section of the ribs and the vertebral column with separated vertebrae at the T5/T6 [editor's note, vertebrae 5 and 6] level with a rupture of the spinal cord”.

In layman's terms, the young man had part of his vertebral column and spinal cord ripped out by the explosion and he would certainly have died on the spot. The doctors also pointed out a long list of “external trauma wounds” on the upper body, which they explain by the body being thrown forward and falling after the explosion.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“According to the information from the inquiry, at about 2am on Sunday October 26th, 2014, in the course of a confrontation between mobile gendarmes and opponents, an offensive grenade was thrown,” write the experts. “Following this discharge the gendarmes are said to have noticed, when they lit the area, that Monsieur Fraisse was stretched out on the ground, his face against the earth. They then went to get him and are said to have dragged him to bring him in and carry out first aid. It was noticed that the backpack that he was wearing appeared shredded. The external examination and the post-mortem examination have allowed the identification of a group of lesions consistent with a blast following an explosion in contact with or a very short distance from the upper thoracic region leading to the lung, spine and spinal cord trauma which caused death.”

As for the rough blotches that they found on Rémi Fraisse's body, these were “consistent with” contact with something abrasive or with the effects of heat though they note that there was nothing to indicate burns caused by flames, and no particles were found in the wounds. “The other trauma wounds found, notably those on the front [of the body], and in particular the face, are compatible with a fall and/or being thrown forward” immediately after an explosion, they explain.

Bernard Cazeneuve has now banned the use of the offensive grenades pending the outcome of an inquiry. These are weapons that are only used by the gendarmes and were used in World War I.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter