The so-called Twitter Affair that began in France late last year involved the writing of racist, homophobic and anti-Semitic comments on the micro-blogging site. Dubious and offensive hashtags – the keywords used in Tweets – led to legal action in this country to force US-based Twitter to take action and remove the offending messages.

But the controversy could eventually have wider consequences, leading to unprecedented reforms of French laws governing free speech on the web. On January 29th 2013 Interior Minister Manuel Valls referred to what he called a “torrent” of unsavoury messages on social networks, including anti-Semitic and homophobic messages and also “the publication of the image of the corpse of one of our soldiers killed in Somalia”, and said they “raised the question of freedom of expression on the internet”. Official spokeswoman Najat Vallaud-Belkacem said the government has decided to deal with what she described as the “lawless zone” that is the web.

To provide a legal framework for a freedom of expression that is abused by some internet users, the Green senator and academic Esther Benbassa has been asked to head a working group on a “new law on the freedom of the internet” that could be introduced by the autumn. Among the areas of reform that have already been mentioned, one notable possibility is a wide-ranging reform of the 1881 law on the freedom of the press, to make it easier to suppress comments on social networks, and also the possibility of an obligation being imposed on each website, portal or web host provider to have an “editorial director” legally responsible for all published content.

Such measures would lead to a radical transformation of debate and discussion on social networks and has already alarmed groups who defend the rights of internet users.

Despite the stance already taken by some ministers and the announcement of the possibility of a new law, these key issues have not as yet been referred to the Conseil national du numérique or National Digital Council, even though it is the official advisory body for the government on such matters. When questioned on the issue the council's president Benoît Thieulin said: “It would be a great issue to be referred to us, or even for us to consider ourselves. The council was created for exactly these types of questions.”

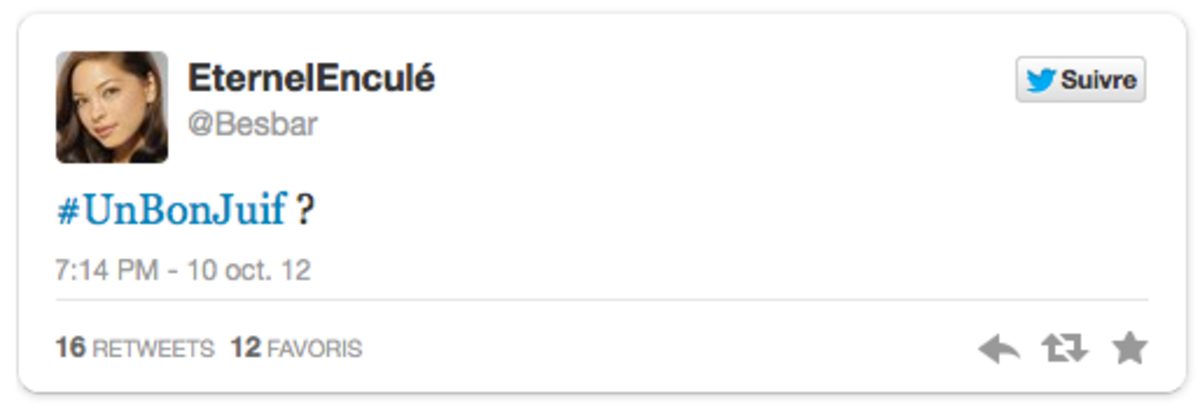

The Twitter Affair itself started with a simple Tweet from what is known in the jargon as a “troll”, someone who posts deliberately inflammatory or provocative material on messageboards or social networks, including dubious “jokes” about women, black people, Arabs, Jews and so on. Until now they have largely passed unnoticed by the wider world. But in the late afternoon of Wednesday October 10th 2012 an internet user Tweeted using the hashtag “#UnBonJuif? (“A Good Jew?”) as a provocation (see image above).

In just a few hours this hashtag had become the third leading topic of discussion on Twitter in France and for several days dozens of users took part in a nauseating contest of anti-Semitic jokes. Initially Twitter, which is based in California, turned a blind eye to the controversy the affair was causing in France and hid behind American law.

More than a week after the first messages appeared, various pressure groups, France's Jewish Students' Union the Union des étudiants juifs de France (UEJF), the International League against Racism and Anti-Semitism (LICRA), the Movement Against Racism and for Friendship between Peoples (Mrap) and SOS-Racisme, managed to get the messages removed. But for those associations, that was not enough. They applied for summary judgement against Twitter to obtain the names of the owners of the incriminating accounts and to compel the site to put in place a more effective alert mechanism.

On January 24th a court in Paris ruled in their favour in demanding from Twitter that they hand over the identities of the authors of the incriminating messages, in view of likely future legal proceedings, as well as requiring “the implementation of a simpler and more complete system” of reporting illegal content.

Alongside these legal manoeuvres, the Twitter Affair also became a major political issue. The controversy increased when, after #UnBonJuif, came other equally disturbing hashtags, such as #unjuifmort ('A dead Jew'), #SiMaFilleRamèneUnNoir ('If my daughter brings home a black man') and #SiMonFilsEstGay ('If my son was gay'). The government handed responsibility for the affair to its official spokeswoman and Minister for Women's Rights Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, who on February 8th organised a round table meeting between Twitter and the various rights associations. Twitter offered to give the associations a “privileged status” of priority reporting that would trigger the sending of messages reminding internet users of "the law”.

But many consider that this offer does not go far enough. On February 15th the UEJF formally rejected Twitter's offer. “We don't want a privileged status or link with Twitter,” said the association's president Jonathan Hayoun, who said that would mean taking part in a system that relied on negotiations. “We don't want to negotiate our room for manoeuvre, we want them to observe French law!”

'Our problem will be how to supervise the internet without undermining free speech'

Over and above the Twitter row there seems to be a consensus emerging to supervise freedom of expression on the internet more strictly by reforming the various laws concerned. During the International Forum on Cybercrime held at Lille in northern France in late January, Manuel Valls floated the possibility of moving some press crimes into the country's criminal code, such as being an apologist for terrorism, inciting racial hatred and making racist and anti-Semitic comments. That would mean they would no longer enjoy the benefits of the 1881 law on the freedom of the press.

According to the specialist IT site PC Inpact this reform, which had already been suggested under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy, would give investigators more powers. These would include the possibility of being able to get alleged offenders put under judicial supervision pending any future trial, of getting suspects put in temporary custody or obtaining fast-tracked court appearances. Valls said at the time of the Lille gathering: “Clearly there is a question posed today as to whether, taking account of the power of the internet and its influence on citizens, the tackling of such crimes should still come under that [1881] legislation.” The minister has announced the setting up of an inter-ministerial working group with experts from the ministries of the interior, justice and productive recovery – the ministry that handles the digital economy - to consider the matter.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Other possible avenues of reform were discussed during a Senate debate on February 7th, when France's upper chamber of Parliament passed a law that changed the statue of limitations on prosecutions for discriminatory comments based on a person's sexual orientation or disability. Under the 1881 law the statue of limitation for such prosecutions was just three months, and it has now been increased to a year to bring it in line with discriminatory remarks based on race, ethnicity or religion.

During the debate on this law change, the question of free speech on the internet was widely discussed. “The internet is a new phenomenon that requires us to modernise our legislation, including the [press law] of 29th July 1881,' said Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, opening the debate. “We will perhaps be wary when changing the 1881 law, but you should know that we are nonetheless firm and determined. I want to repeat this here: the internet must not be a lawless zone, a place of sanctuary.”

This blunt assertion set the tone for the discussions that followed. Yet even if legal action against offenders on the internet is less easy than in other countries, the French web is far from being a “lawless zone”. And everywhere in Europe internet users are regularly convicted for illegal postings they have made on websites or social media platforms.

Going beyond the immediate debate on the change in the law, some Senators expressed the desire for a completely new law on the freedom of expression on the internet. One of the suggested reforms was to place a general obligation on owners of websites, social network platforms or those hosting them to have, as media organisations currently do, a nominated editorial director. This would make that person legally responsible for the content on the website or social media platform. That was the view of the Socialist senator Jean-Pierre Sueur, who is also president of the Senate's law committee. “Nothing should be able to be published without a person in charge on the publication being specifically designated,” he said.

These various proposals could find their way into the proposed legal reform for supervising the internet being overseen by Green senator Esther Benbassa. “A reform which will of course preserve freedom of expression, that goes without saying, but which will at the same time introduce rules preventing defamation and abuse,” she told Mediapart.

“Our problem will be how to supervise the internet without undermining free speech. I am aware that this is a very delicate question because one can very quickly undermine freedom of speech,” said the senator. “But words can also kill.”

Making a site owner an editorial director

Enlargement : Illustration 3

This trend towards greater restrictions on the freedom of expression on the internet is nothing new. Under the 2004 Law for Trust in the Digital Economy the web hosting provider is subject to a form of “limited liability” under which they are obliged to remove all clearly illegal content once they are informed of it.

But according to PhD student Félix Tréguer, a specialist in internet freedom of expression issues studying at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, there has in recent years been a “constant pressure at a legal level on web hosting providers to play a bigger role in the suppression of illicit content, or content that is judged to be illicit”.

These pressures, says Tréguer, who is also a volunteer at the internet free speech advocacy group La Quadrature du Net, leads these private companies to play “the role that editorial directors play in the traditional public arena”. He adds: “Yet often, and even for a legal expert, to work out the legality or not of content is not an easy issue. Moreover, under the rule of law any restriction on freedom of expression should only be a matter for a judge.”

The danger is that, faced with the risk of being taken to court and to have its legal responsibility tested, the web host providers often choose the path of caution. Rather than get involved in a legal battle over the legality of such-and-such a comment, the web platform providers prefer simply to remove contentious material.

To highlight what some see as a form of extra-judicial censorship, at the beginning of January Twitter published a website on which they show all the demands they have received for information to be removed. The figures show that in the second half of 2012 there were a total of 42 government, court, police or other formal requests to Twitter to remove information from the micro-blogging site. One of these was from France – the request from the UEJF mentioned above - which was granted. In contrast there were 16 court requests from Brazil, none of which were granted. Indeed in only two cases – the one in France and another in Germany, mentioned below – did Twitter remove information at the request of a government, court or other authority.

The same site shows that when it comes to requests for information by governments about Twitter account users - typically in connection with criminal investigations or cases, says the site - France comes fifth in the league table with 12 requests in the second half of 2012. None of the requests were granted.

According to blogger Laurent Chemla, an author and computer and internet expert, regular attempts at legal action, of which the Twitter Affair is but the latest example, should in theory force websites, web host providers and web platforms to put in place filtering procedures and moderation of content. “Our main concern is not to punish those in charge but to guarantee that, in the future, we will have the means to ban all disturbing comments through an intermediary without needing to go to a judge,” he wrote in a blog published by Mediapart.

But as already stated, the main danger in handing over to a private company the role of judging whether content is illegal is that these firms become overly cautious and censure information that is completely legal. “Many web platforms, such as Facebook and YouTube, have long since put in filter systems that scrutinise communications according to a marking system. Yet there are already many cases of improper withdrawal of perfectly legitimate and legal content,” says Félix Tréguer. “The problem is that in contentious cases we rarely get the other side of the story because the content is withdrawn and no investigation is carried out.”

Another issue is that in wanting to impose their national law on American firms – such as for example Twitter – nation states are calling into question the global nature of the internet. For example, in October 2012, Twitter for the first time agreed that, in Germany only, it would ban a neo-Nazi account. This was the case mentioned above. Yet if Twitter agrees to apply French and German law, how should it respond to a demand for information about account holders from say Iran, Saudi Arabia or Russia? “But France isn't either Iran or Russia,” says Esther Benbassa. “That makes all the difference.”

Clash of cultures

Over and above the various legal and political issues, what we are seeing is a genuine culture clash caused by the position the internet now occupies in society. For many years politicians have been somewhat indulgent towards the web, allowing it to grow and develop according to its own rules. Therefore the notion of an almost absolute freedom of expression was applied to the web, as the internet was considered to be a new territory where national laws did not really apply.

Yet with the explosion in the number of users and the economic issues at stake, these libertarian principles have ended up falling foul of the laws of many countries. “With Twitter you can express yourself just as everyone was able to do up until now in private circles,” says Paul Da Silva, former president of the freedom of information party Parti pirate (Pirate Party) who on his own website has analysed the messages involved in the Twitter Affair. “It's just that now it's a bit more public.” Meanwhile countries have decided to call an end to the free-for-all and re-assert their sovereignty.

In such circumstances, reconciling this almost total freedom of expression with French law seems a particularly delicate operation. “For example, for an American, the concept of [the offence of] incitement to racial hatred is in itself an offence against freedom of opinion, because it leads to punishing expressions that do not call for the direct commissioning of an offence or crime,” says Félix Tréguer. Paul Da Silva says that the Twitter Affair is, from an American point of view, seen as an “attack by France against freedom of expression”. He adds: “Without going quite that far – for we must recognise that overall there are quite a few things out there that have nothing to do with freedom of expression – a balance must be found. But we're not there yet...”

Félix Tréguer says that restrictions on freedom of expression as defined in the 1881 press law in France seem “difficult to apply to the internet”. Tréguer adds: “The freedom of the press law dates back 130 years. Even if it has been adjusted in certain aspects, it is not adapted to these new questions concerning the freedom of expression. We need a major new law on the subject to take into account changes in technology and society.”

Esther Benbassa recognises there is a clash of cultures. The senator says it is precisely for that reason that there is a need for a tighter supervision of freedom of speech. “We were not brought up in the same way as they are in the United States,” she says. “We're not the same society, we don't have the same vision. Our children are not educated in this freedom of expression. We haven't learnt how to domesticate it as the Americans have done. That's why we need to legislate.”

However, according to Paul Da Silva there is a risk that in doing so one of the founding principles of the internet will be put at stake. “The specification for the internet at the beginning was 'Make us a network that will survive a nuclear attack'. Well, it seems we have succeeded in creating something that will indeed survive a nuclear attack. But not a political one. That will be the specification for version 2...”

-----------------------------------------

English version: Michael Streeter