French President François Hollande pledged during his election campaign to clean up French political governance, blighted by years of recurrent scandals and conflicts of interest. Among the promises he made was that anyone who had been convicted of crimes would be excluded from government.

Unlike his predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy, whose foreign minister, Alain Juppé, was convicted in 2004 for his part in a corruption scandal at the Paris City Hall, Hollande insisted: "I will not have people around me at the Elysée [presidential office] who have been judged and found guilty."

Yet Hollande’s first act after he was sworn in as president on May 15th was to appoint Jean-Marc Ayrault as his prime minister, despite a conviction dating back to 1997.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Ayrault was found guilty of favouritism in the attribution of a public contract in Nantes, western France, when he was mayor of the city, for which he was given a six-month suspended prison sentence and fined 4,600 euros. He had attributed the contract for printing the Nantes city authority’s newspaper to a businessman close to the Socialist Party, Daniel Nedzela.

At the time, Ayrault was also a Member of Parliament and leader of the Socialist Party group at the Assemblée Nationale, the lower house of Parliament. Nedzela was convicted of influence peddling after an investigation into his suspected illegal financing of the local branch of the Socialist Party.

The affair resurfaced weeks before Ayrault’s widely-expected nomination as prime minister. The day after Hollande was elected president on May 6th, details of the case were posted on a Facebook page set up by a group calling itself ‘Non au PS’ (‘No to the Socialist Party’). The French media were soon speculating whether the controversy would cost Ayrault his promised job.

"It was 15 years ago," he said in a statement. "My personal integrity was never in question. There was never any question of personal enrichment or political financing. I am an honest man and I will remain so."

In an interview on RTL radio on May 13th, Sarkozy’s former labour minister, Xavier Bertrand, insisted that the fact the conviction dated back to 1997 "did not take away any of its seriousness".

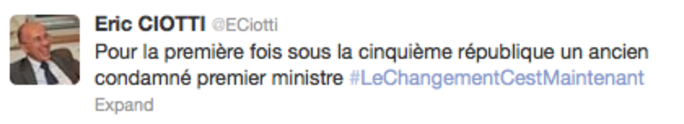

Once Ayrault’s appointment was announced, Sarkozy’s conservative UMP party went onto the offensive. Christian Jacob, leader of the UMP parliamentary group, said: "I take note. I make no judgement. But it is surprising. It is not consistent with what François Hollande said during the campaign." UMP MP Eric Ciotti said on Twitter (see below): "For the first time under the Fifth Republic, a prime minister with a conviction," adding Hollande’s own slogan, "Le changement c’est maintenant" (‘The time for change is now’)

Hervé Morin, defence minister under Sarkozy and president of the Nouveau Centre centrist party, allied to the UMP, went further. "After having hammered home for months that he would be the guarantor of an exemplary Republic [...]," he said, "choosing the rehabilitated Mayor of Nantes as prime minister is a revealing choice in terms of how he [Hollande] sees a so-called exemplary Republic."

In his statement, Ayrault stressed that the matter did not concern him in his capacity as a private individual, "but I took responsibility for it as mayor." Ségolène Royal, a high-profile Socialist Party figure, its defeated candidate in the 2007 presidential elections and a former partner of François Hollande’s, described the case as no more than a "judicial incident".

At the court hearing in November 1997, Ayrault’s then lawyer, Yvon Chotard, said the case against his client centred on a banal "technicality", adding: "On a moral level, nothing was contrary to [his] honour."

A 'serious infringement' of the rules

The affair was first revealed after an investigation was launched in the mid 1990s by the regional administrative court of audit (Chambre régionale des comptes du Pays de Loire) for the Loire region, in which Nantes is situated. Ayrault had been mayor of the city for five years at the time.

In a letter dated February 5th, 1995, the court criticised the management of an association called Omnic that worked closely with the Nantes city authority. Among its contracts was the municipal journal, Nantes Passion.

The court’s financial magistrates found that the association, headed by Ayrault and his communications director at Nantes City Hall, had no real activity and that its aim was "under the cover of a desire for flexible management, to be freed from the rules of public accounting".

Besides what they called anomalies in the remuneration of the association’s staff, the magistrates singled out its main beneficiary – the businessman Daniel Nedzela.

The association hired his services for 6 million francs (equivalent to 915,000 euros) for the printing of all its publications between 1989 to 1994 "with no formal recourse to competition or any written contract." Nedzela was also given the contract to handle advertising sales for Nantes Passion, with a hefty 45% commission.

The court concluded that Nedzela’s company had been handed an unjustly privileged position, saying: "These practices constitute a serious infringement of the rules governing public contracts" (click on Prolonger tab top of page for the court's full report). Ayrault wound up Omnic before the report was even published.

Nedzela, meanwhile, was already suspected of collecting funds for the illegal financing of the local branch of the Socialist Party. Investigating magistrate Judge Renaud Van Ruymbeke led a raid on Nedzela’s company offices in connection with the case in 1992, and the businessman spent several weeks in custody in November 1993.

In September 1997, two months before Ayrault’s own appearance in court, Nedzela was convicted of influence peddling for having been an intermediary between companies and several municipal authorities in the west of France, including Nantes. He was sentenced to three years imprisonment, of which two and a half were suspended, and fined the equivalent of 77,000 euros.

A report by French daily Libération described how Nedzela sold "commercial assistance" to companies, services which in reality contained confidential information on local authorities’ plans to tender for contracts. Whether Nedzela, a Socialist Party sympathiser, passed on part of his commissions for illegal political party funding was never established. But the suspicions surrounding the case left a cloud over the relatively minor offence for which Ayrault was convicted.

A law to keep it quiet?

Meanwhile, Ayrault’s lawyer, Jean-Pierre Mignard, who has links with the Socialist Party (and who acts as legal counsel for Mediapart) said Ayrault’s conviction in 1997 had been "wiped out by a rehabilitation granted in 2007." He also claimed that by "referring to it”, as Ayrault’s critics have done publicly, was tantamount to "putting oneself in breach of criminal law".

In France, someone sentenced to less than one year in prison is rehabilitated in the eyes of the law five years after the sentence has been served. In Ayrault’s case, the sentence is considered to have been served since December 2002, and he has therefore been rehabilitated since December 2007.

While Ayrault’s supporters claim that this in effect means he no longer has a criminal record, a criminal lawyer consulted by Mediapart, whose name is withheld, said the conviction nevertheless still figures in a section of Ayrault’s police record, which is available to the justice system. The lawyer based this opinion on Article 133-16 of the Penal Code, which was in force between 1997 and 2007. In Ayrault’s case, he said, "rehabilitation does not remove the conviction, the facts remain and the courts can even refer to it."

Mignard, however, insisted: "The first part of the police record is not accessible or usable by just anyone. Only the legal system keeps it in its archives. One cannot refer to it under [stipulations of] a law from time immemorial that allows people in positions of power to lead a normal life again."

He cited Article 133-11 of the French Penal Code, under which "it is forbidden to any person who, in exercising his responsibilities, knows of penal convictions […] to recall their existence under any form at all, or to allow the mention of these to subsist in any document. However, minutes of legal judgments and decisions are exempted from this prohibition."

Mignard added that taking out lawsuits against media organisations which mention Ayrault’s conviction would make no sense, since the details of the case are available on the internet and freedom of information is involved. But, he said, "It is an entirely different matter to transgress the law publicly with the intention to cause harm, as Xavier Bertrand did."

"We will probably sue Xavier Bertrand for defamation," he added.

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)