In her 1998 book Les Femmes ou les silences de l'histoire (‘Women, or the silences of history'), the French historian and feminist Michelle Perrot wrote that "the unequal share of traces, of memory and, even more so, of History" had left women, in comparison to men, in a position "as if outside of time, or at least outside of events".

So it is that, with depressing regularity, French school teaching books continue to offer a stereotyped, partial, sexist and always minimal record of the place of women in History.

That sad conclusion emerges from various studies and reports on the subject, notably that commissioned by the government in 2004 from the historian Annette Wieviorka, and another, in 2009, by the French High Authority for Equality and the Fight Against Discrimination, the Halde.

This approach runs against a broad evolution in public recognition of the important and overlooked role of women in the making of history, shaking up the previous caricatures that relegated them to a shadow part, and is all the more regrettable given the influence of schoolbooks on the forming of symbolic representations in the minds of pupils who often lack any other points of reference.

Which is why the Hubertine Auclert Centre, a semi-public institution for the promotion of gender equality set up with funding by the greater Paris regional authorities, launched a study of 11 school teaching books concerning the 2010 teaching programmes both for those studying for the basic technical skills diploma, the CAP, and those in second grade studying for the baccalauréat, broadly encompassing 16-17 year-olds.

The study was this month presented to a jury, presided by historian Annette Wieviorka, with the aim of awarding prizes to those teaching books which accurately presented the contributions of women to the major events, movements and social and working activities that have shaped history.

The study found that of the 339 historicalbiographies contained in all of these teaching books, only 11 of these, or 3.2%, were about women subjects. Furthermore, women contributors to the books accounted for just 4% of the authored works (3.5% for political subjects, 2.8% for artistic topics and 5.2% on the general field of knowledge).

The study, led by the Centre's director for educational affairs, Amandine Berton-Schmitt, detailed the manner in which women were all too often relegated to the margins of history, beginning with the accounts of citizenship in Ancient Greece, where they are placed as a sub-category of those who were excluded from mainstream society, like slaves, those of mixed race and children. As if women were not also slaves or of mixed race.

Women absent from the Middle Ages

While recent historical research has detailed the important role of women in the 1789 French Revolution, the report found they were largely absent from the historical portrayal of the events in the school books for second grade pupils (broadly, 16 year-olds), with the exception of a few emblematic figures such as Olympe de Gouges. While the phrase "universal male suffrage", in passages devoted to the granting of the vote to all men, appears in several teaching books for CAP students (those following courses for a basic technical skill diploma), most offered no particular explanation concerning the achievement of universal suffrage, when the right to vote was extended to women (inscribed in the French constitution in 1944).

Some of the books carried illustrations reducing the suffragette movement to one that was less concerned with broad political issues than the concerns of housewives and mothers. Amandine Berton-Schmitt cited the example (see below) of an engraving promoting the suffragette campaign in which a line of women queue up before a ballot box covered with a poster reading: "Against alcohol, slums, war".

"For the Middle Ages, if you take out the Virgin Mary, there are no women", commented Berton-Schmitt. "Or they stay tied to masculine imagery, the sinner, the dame of courtly love." The established key role of women in agricultural families and communities, in small trades and businesses is never referred to in the texts or illustrations. The report notes that "this absence of women in the world of working activities, from Ancient times up to 1848, via the Middle Ages, contributes to a definition of work as [being] masculine".

'We won't invent grand women who aren't'

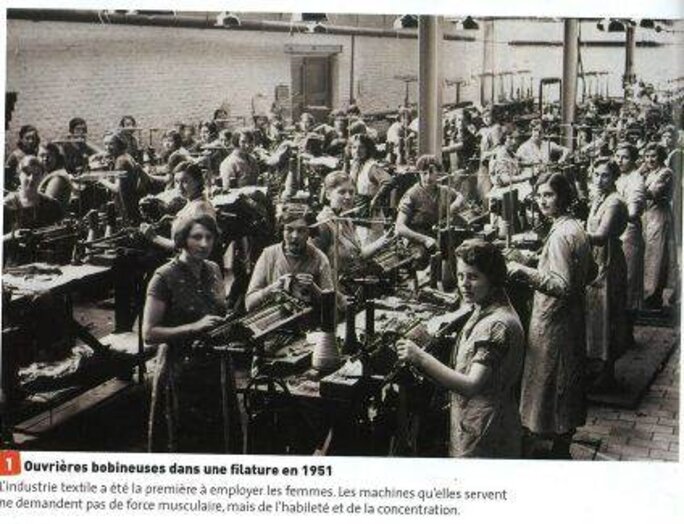

In general, the description of the place of women in economic production is still very stereotyped. The thematic titles, such as "Being a workman in the 19th and 20th Centuries" leaves little space for recognition of the truly mixed nature of the working world. The Industrial Revolution is presented, in text and illustrations, as a virile event, passing over the large contribution of women during this new era of production activity.

When women workers do appear, they are in the textile industry, with commentary suggesting that technical progress had vastly improved their working conditions. Historian Annette Wieviorka, presiding the jury, underlined that this was far from the reality of conditions that were "close to enslavement, in front of their machines 12 hours per day".

While the 2010 teaching books did include some new entries regarding women who contributed to the intellectual, scientific and cultural history of France, like the mathematician and physicist Emilie du Châtelet, an important scientific figure during the period of the Enlightenment, they remained largely anecdotal figures. Even Emilie du Châtelet, when she is mentioned, is often presented simply as the translator of Isaac Newton's Principea Mathematica.

The jury was scathing: "Given the results of the study, there will be no prize of excellence awarded this year," commented Wieviorka. The closest any came to a top prize was a general history manual for second grade pupils, published by Nathan and edited by Guillaume Le Quintrec, which received "the encouragement of the jury".

A tongue-in-cheek Le Quintrec said he was "happy to be the least worst of the class", and defended himself and his colleagues against some of the findings. "We have to make choices, to simplify a great deal," he argued. "We also apply programmes where traditional political history dominates. That of ‘grand men' and which does not necessarily lend itself to a history of the gendre. Concerning the absence of women in biographical notes, we aren't going to invent ‘grand women' who don't necessarily exist."

Annette Wieviorka dismissed the comments. "This is no longer an argument," she said. "[...] we have today all that is needed to propose a mixed [account of] history."

-------------------------