France-based American photographer Jane Evelyn Atwood has focused her work upon portraying the excluded and the outcasts of society. Her haunting images capture the eclipsed conditions of the sick, the blind, the handicapped, but also those of prostitutes and prisoners, revealing lives and worlds that are largely kept hidden from view. An exhibition celebrating her photography, spanning more than 30 years, is now on in Paris. Here, Clément Sénéchal presents Atwood's work and interviews the photographer about her approach and experiences.

-------------------------

A Jane Evelyn Atwood exhibition can be a painful experience. Our blinkers are removed before a mixture of bitterness and tenderness, and the movement of our eyes is weighed down with something approaching responsibility. Atwood's photographs arrest our gaze. Seeing is not harmless, they seem to say.

Have we lost the habit of seeing, moving so swiftly through environments designed to favour flow and transport with as much comfort - and perhaps indifference - as possible? Or is it our society that strives to conceal anything that might shake the images of happiness forged by the media and advertising?

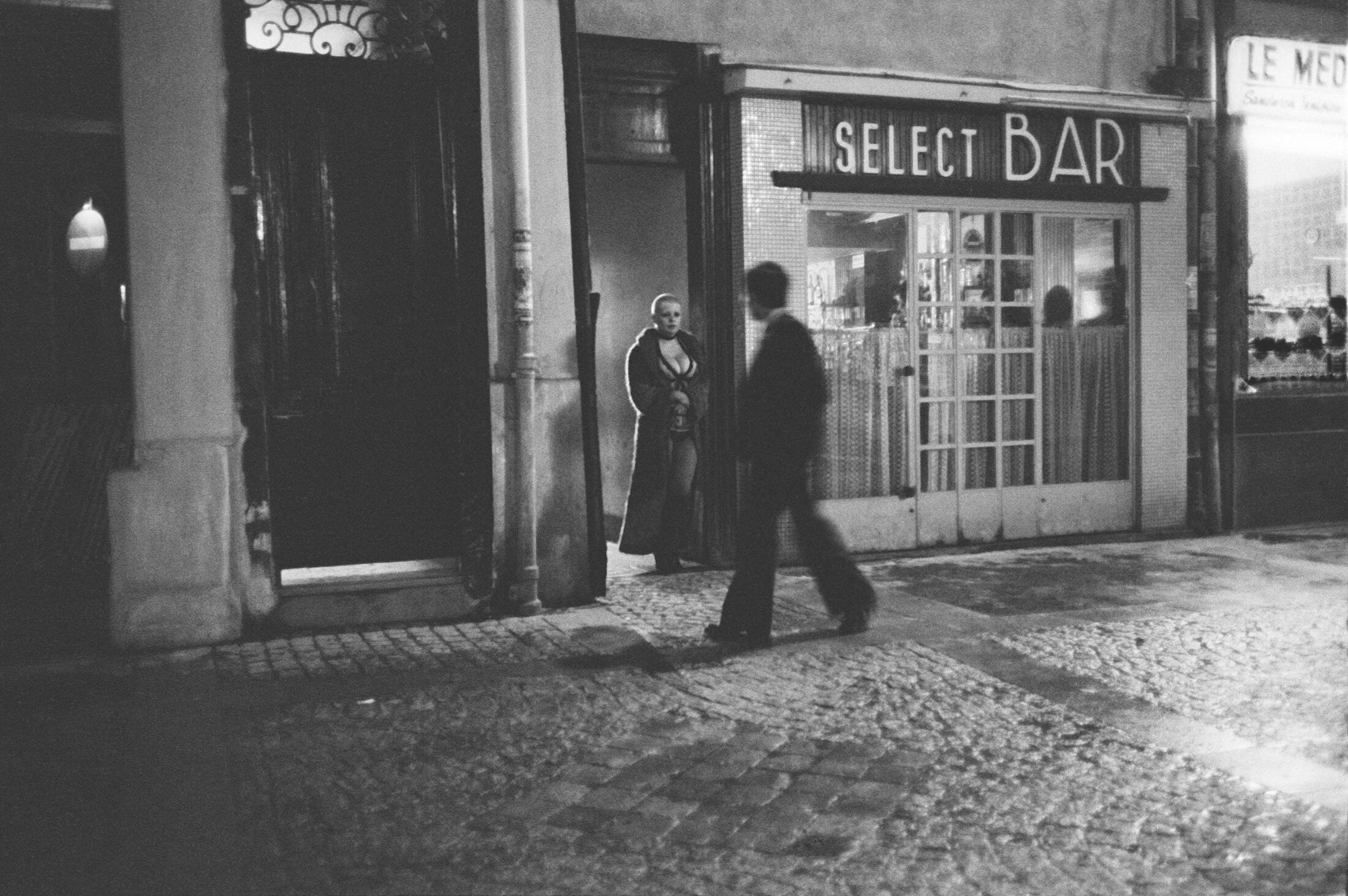

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Our notion of the visibility of the world and people is radically changed by Atwood's photos. Silence falls before these faces that turn inwards, awkward in front of the photographer's lens, masked by the stigmata of exclusion. Atwood provides us with a way into the closed worlds that our societies have built to relieve their difficulties, spaces conceived to exclude. She presents us with an ardent view of these sorting systems.

Atwood reveals to us the astonishing intrinsic dignity of these alienated people, who are pushed aside from the world by the happenstance of life, the arbitrary, by contingency - by injustice. In detention centres, by-the-hour hotels, hospital wards, bodies at the in his right eye desperation, indifference and the disappointment of having missed death, discouragement faced with the prospect of a return to this life that isn't worth the effort. The photo is titled: Suicide attempt, Belleville metro station, Paris, France, 1996.

This photographic retrospective leaves viewers with a slightly more informed awareness of the world. Atwood seems in any case to suggest to us that the efforts we make to forget it are perhaps, as well as infantile and cowardly, an absurd solution. It is not physical handicap that wounds the humanity of women and men, but the exclusion that others make them endure. The harm is not in a lost leg, but in averted eyes. It is this averted gaze that Atwood has spent her life returning to the destitute and powerless, making up on her own for our general indifference.

Focussing on the excluded

Jane Evelyn Atwood was born in New York in 1947. She emigrated to Paris in 1971, obtained her first camera in 1976, and started photographing prostitutes in the street. She captures the fugitive, the shadow in movement, elusive nooks and crannies, the evasive nerve of prostitutes, their low-key grace, their lingering, on the rue des Lombards.

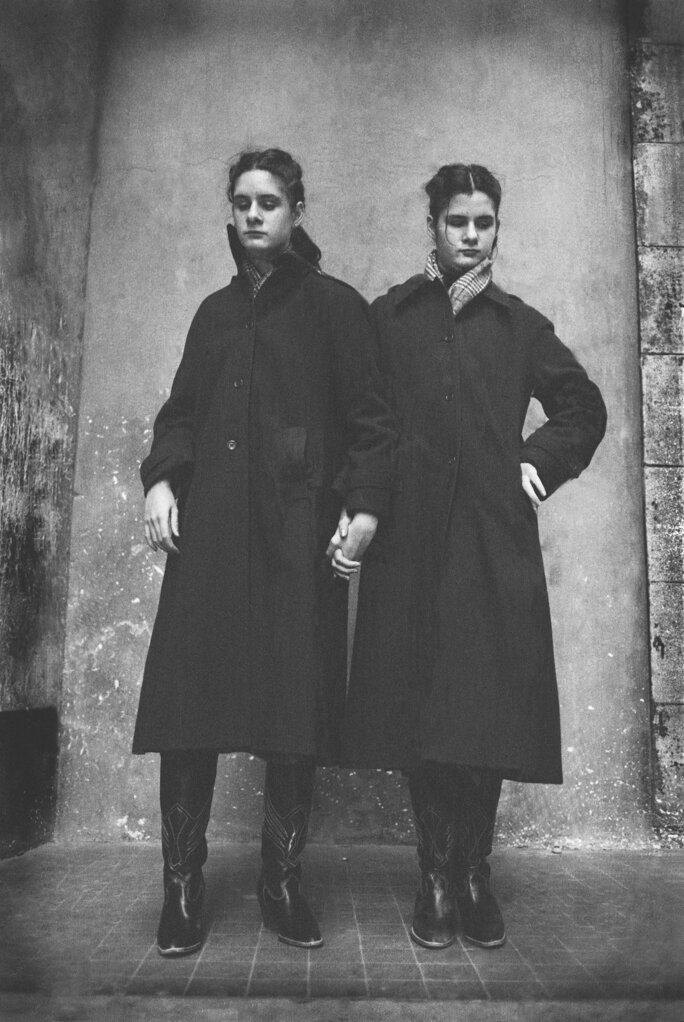

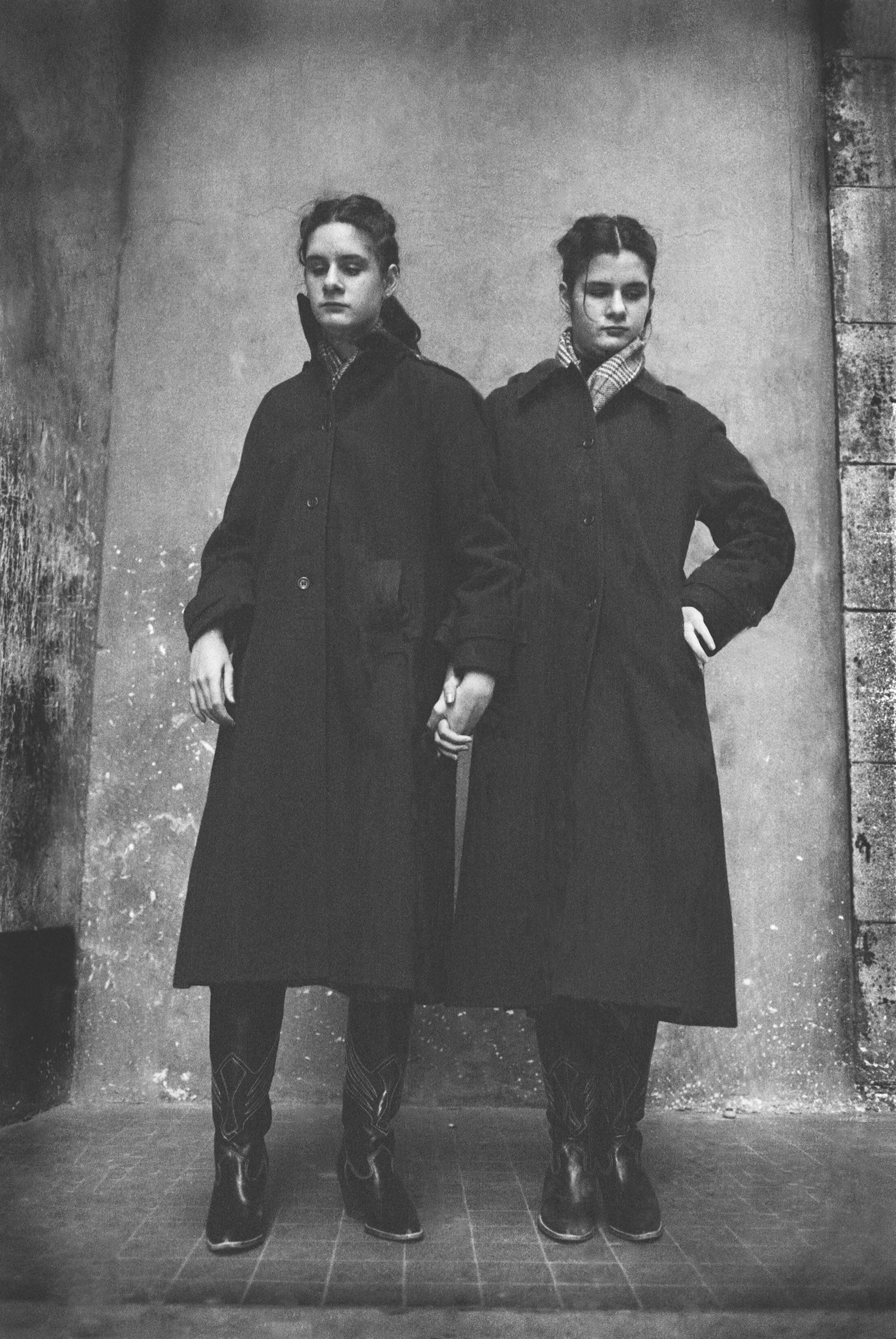

Enlargement : Illustration 2

A little later, in the 1980's, she went into a school for the blind, and emerged with a series of magnificent portraits, where the singular poetry of the gentle, tentative, careful movements of the blind is revealed. A different temporality, a different way of presenting oneself, of being simply out of joint with our usual perceptions.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

And then there is her work on prisons, to which she dedicated ten years, mixing with women inmates. Her work is an indictment of the death penalty. Jane Evelyn Atwood relates the remorselessness of the systems of control, of captivity where life is slowly extinguished for lack of oxygen and meaning.

Next, the photographer focused on victims of antipersonnel mines: people missing one or several limbs, who have become incomplete figures, unrecognisable. For this Jane Evelyn Atwood travelled to Cambodia, to Mozambique, to Kosovo, to Angola and to Afghanistan. During these adventures she was almost blown up by a mine herself. In her photos you see crippled people playing basketball with incredible energy, mothers with heads held high, fathers, children already maimed.

One series is dedicated to an AIDS victim, transformed into a skeleton by the illness. Jane photographs the pain of his everyday life, life burning out from exhaustion. These shots do not steal, they return, giving back to these deserted women and men the attention others used to give them, before their lives were brutally changed.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Finally there are the photos of Haiti, taken before and after the 2010 earthquake. Buildings shattered, bodies torn apart, the vast carcass of a horse laid out on its side on the asphalt of a road, rust and polished concrete, tankers in the bay, domestic activities, their humility. And despite everything, there are these bright colours that perhaps help maintain dignity, like the colourful little girl in a pretty pink dress, sweeping with a blue broom, stern-faced in the golden glow of sunlight.

Interview

Mediapart: Your photographic work covers handicap and exclusion. What do you believe is the role of the photographer, what is their mission?

Jane Evelyn Atwood: I don't like the word mission. My photos have a life of their own. They don't need to belong to a project beyond themselves in order to exist. I take photos above all to satisfy my obsessive curiosity. I'm fascinated by exclusion, by closed worlds. This began with my work on prostitutes. I'm fascinated by the way people in situations of real distress manage to get on with their lives regardless. When I see that woman in the Landmines series who no longer has any legs and only one arm, and who has to bring up her child, I ask myself how she manages to get up every morning to go on living.

Mediapart: Is your work that of rendering visible the invisible?

J.E.A.: Yes, I think you can put it that way, even if I don't think about that when I'm in the thick of it, working.

Mediapart: How do you work on the aesthetics of your photos?

J.E.A.: You tell me. I'm a professional and I always try to take good photos. But I think people are beautiful in themselves, these women, these children. Blind children have a particular grace. Everything they do with their hands...they don't use them only for communication, as others do... They move in a way that's different from other children, because they're afraid of bumping into something. They move cautiously, without any violence. That creates a magnificent poetry.

Mediapart: How do you choose your subject?

J.E.A.: It's almost always something visual that triggers my curiosity. Regarding my series on blind children for example, every day I used to take a bus that went right past the national school for blind children at Duroc, in Paris. Three young blind people would regularly get on. I watched them, fascinated, for weeks. At one point the bus was reconfigured so that the place where the three young blind people usually sat had disappeared. They got onto the bus and started to feel around. It was very beautiful. Of course everybody stared at them. So one day I decided to go look behind the school walls, and took all these photos.

Mediapart: How does one approach these people who are going through really tough times when one isn't in such a difficult situation oneself?

J.E.A.: I've never tried to force anybody to let themselves be photographed. I simply explain to them why I want to photograph them, what I intend to do with the photos, and I often show them the result. They frequently ask legitimate questions, and answering these inquiries is part of the photographer's job. You know, people let themselves be photographed for all sorts of reasons. It took me a long time to understand this myself. I went through a long psychoanalysis of about nine years, which helped me to understand who I am and, no doubt, at the same time, who these other people are. I think we probably have pretty similar preoccupations at the end of the day. There's a kind of proximity that helps them to accept me.

Mediapart: Have you discovered points that all these people have in common? The blind, the disabled, prisoners, disaster victims, who have no other connection other than being excluded?

J.E.A.: They all carry within themselves rejection by the rest of the world, and are inhabited in their existence by a sort of madness, a latent distress. There is only one world, which we all live in, and we should include everybody in it. Alas, people are afraid of those who are different from them, of strangers. People are afraid of that blind kid who has one bulging, empty eye. And yet he's only a child.

Mediapart: You're publishing a book of your first photos, all about the prostitutes on the rue des Lombards, in Paris. What do you think about the current debate on the subject, the punishing of clients, reopening brothels, and so on?

J.E.A.: I'm against the idea of punishing clients, which wouldn't be effective anyway. It would above all isolate prostitutes and make their work even more dangerous. Because it wouldn't stop prostitution. That's an illusion. I decided not to sell my body, others made a different choice, for various reasons that I'm in no position to judge. What goes on between consenting adults is none of my business. On the other hand, we do have to fight pimping, which is of course a real scourge. But we already have laws against slavery, don't we?

Mediapart: What did you feel when you visited women's prisons?

J.E.A.: Women are treated like second-class citizens there. Lots of women who've been abused outside prison walls continue to be treated wretchedly inside. There's no work for them. In France they're locked up in their cells 23 hours out of 24, with a ten-minute shower once a week [...] The atmosphere's drenched in fear, because everybody's at the mercy of this penitentiary system. My exhibition is dedicated to Corinne Hélis, who died in a French prison because the director refused to let her keep the Ventoline she needed for her asthma in her cell. It was an arbitrary decision that ended with the death of an inmate. It's not necessary to go all the way to India to die in prison.

Interview

Mediapart: You went to Haiti to take a series of photos, then returned there after the earthquake. What did you see?

J.E.A.: I went there a first time for a commission. Then I decided to dedicate a more in-depth work to the subject, which took me three years, and resulted in a book. Two years after it was published, the earthquake struck. So I went back. It was an unbelievable spectacle of desolation, total destruction, with those wrecked buildings that refused to go down, and that are still there today, like that, half-collapsed.

Mediapart: Is there a strong political engagement in your work?

J.E.A.: Political engagement comes despite myself. My position can be read from the evidence in my work. For instance, I couldn't have considered my series on women prisoners without a photo of a woman on death row, to say, ‘Look, this is what's happening in the United States'.

Mediapart: You were almost a victim of an anti-personnel mine. Have you never said to yourself that you should stop?

J.E.A.: No, if I started to fantasize about everything that could happen to me while reporting... I don't allow myself to think about death. I just try to be very careful. The world is more dangerous than a few years ago. If you're a white American woman, there are countries you'd be better off not setting foot in. Taking photos is no longer, alas, the adventure it once was.

Mediapart: Having encountered all those cruel destinies, can you still find a point to life?

J.E.A.: A journalist once asked me if I didn't leave a part of my soul in each shot. No, I don't leave my soul in those photos. On the contrary, I enrich it each time, I take back supplementary fragments every time I go home, having investigated such and such a world. Once I've lived in those worlds that are closed off from others - not closed by the people in them wanting to be hidden, but by people who don't live there and want those who do to be hidden - I feel much richer.

Mediapart: Do you stay in touch with them once you've finished work on your subject?

J.E.A.: Yes, often. Of course it's easier with those who are in France. For example, I gave several prints to the prostitutes I'd photographed in Paris during the 1970's. In fact you can see them pinned up on their bedroom walls in some of the photos on show here. I'd also given a postal box address to the prisoners, and many of them corresponded with me afterwards. They weren't allowed to receive my photos in prison, but they could ask me for them once they were out. I gladly sent them.

Mediapart: How does one leave these people who are in such distressing situations? Do you forget them?

J.E.A.: No, never. And if I didn't manage to use the photos in books or exhibitions, I'm sure I'd go crazy. The work needs to be seen by the public to be complete.

Mediapart: Aren't you sad to leave these people, to live far away from them?

J.E.A.: That's a question I've never been asked before, though it's a very good question, fundamental even. Thank you for asking it. I am always sad, indeed, I'm always sad when I leave my subjects. But I know when the subject's finished, when I have enough experience with them, enough photos. Even if it is, in fact, very difficult for me to stop. These people I meet, it's banal to say it, but I love them. And often that pushes me to work a bit longer, the time to find the courage to go, to leave them. Afterwards, I need a certain weaning period before starting on a new subject.

-----

The exhibition Jane Evelyn Atwood, Photographs 1976-2010, is on in Paris until September 25th at the Maison européenne de la photographie, 82 rue François Miron in the 4th arrondissement.

-------------------------

English version: Chloé Baker

(Editing by Graham Tearse)