In 2004, Professor of Applied Arts Zvonimir Novak travelled to the wealthy western Paris suburb of Saint-Cloud, where he had an appointment at the headquarters of the French far-right Front National (FN) party. His object was to beef up his collection of "little papers", as he calls them: printed propaganda in the form of posters and pamphlets, flyers, stickers and decals, badges and insignia of all sorts."The FN was one of the few parties that still had its own graphic design service," Novak explains.

Inside Le Paquebot, the name given to the FN's ocean liner-like building, an official let him rummage through the party's stockpiles, where he found years and years of print campaigns stacked up. "I helped myself as I walked through," he recalls. "They didn't even ask if I supported the party. I was surprised that they'd be so naïve."

After "ten years of research and three years of writing", Novak has put together a remarkable compendium of arresting images drawn from campaigns of the French political Right, from 1880 to current times, entitled Tricolores: une histoire visuelle de la droite et de l'extrême droite (‘Tricolours: A Visual History of the French Right and Far Right'), published in 2011. It follows an earlier work, La Lutte des signes (‘The Struggle of Signs'), published in 2009, in which he catalogued 40 years of left-wing political stickers.

Novak began collecting his "little papers" in 1978. "I was a far-left libertarian militant with a passion for political graphic design," he explains. He hung out at all the meetings and demonstrations - "where you find real gems" - as well as trade fairs and collectors associations, ever on the lookout for even the slightest scrap of printed propaganda, eventually amassing a hoard of 20,000-odd items. "There is cohesion there, you can actually follow a party with nothing but these documents to go on," he explains.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In ‘Tricolors', Novak traces the widely different currents across 130 years of French right-wing political history, from Boulangisme, an 1880s reactionary movement regarded as the first organised manifestation of French national populism, to ‘bling-bling' Sarkozyism via a slew of National Front slogans. In all, the book contains 800 illustrations and hundreds of apposite anecdotes.

One question his publishers and book dealers had to grapple with was whether they should actually provide a showcase for xenophobic, anti-Semitic and racist refrains. Novak was certain that the themes of the far right should be displayed in order to "undertake a critical decoding" of this visual and verbal rhetoric.

Over the following pages, Zvonimir Novak commentates for Mediapart a selection of the posters and campaign paraphernalia featured in his book, and (on page 5) compares recent print campaigns of the ruling conservative right UMP party and the FN.

The Far Right

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Front National, 1977 (above). This is a sticker I peeled off. The FN used it, with variations, in three different periods (1977, 1982 and 1987). It plays the immigration card (linking it to an issue that is not racial, but social: unemployment). It was this approach that catapulted the FN to their first electoral victory in Dreux [Editor's note: a town 80 kilometres west of Paris], in 1983.

This slogan was basically thought up by François Duprat [a French Holocaust denier assassinated in a car-bomb explosion in 1978]. Duprat was the mastermind of Ordre Nouveau [Far Right movement created in 1969 and merged with the newly-founded FN in 1972] and second-in-command of the FN. [Party leader] Jean-Marie Le Pen was not in favour of using it. This theme emerged in 1971 during an extremely violent first meeting, which culminated in a riot in the Latin Quarter of Paris, where party members squared off against 800 leftists. I was there. These stickers are tricolour, but the red and blue predominate, exactly as in the Spanish neo-Francoist movement Fuerza Nueva. Red subsequently ceased to be a dominant colour in FN print campaigns.

Front National, 1990 (right). Jean-Marie Le Pen often wears costumes on his posters, posing as a football referee (2000), Zorro (signed "Zean-Marie Le Pen", 2007), or a corsair captain (2009). Here we see him dressed up as an American Indian, an idea he stole from his opponents in the anti-Fascist movement Scalp. The maritime metaphor (he is a Breton) often recurs in his visuals: he is the rock, the invincible force of nature. These campaigns smack of a personality cult. His deportment, the way he often holds his head high, is typical of the Far Right.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Front National de la Jeunesse (FN youth wing), 1992 (left). This poster is emblematic of the FN's modus operandi. They proceed by implication and insinuation. Unlike the neo-Fascists, the FN don't come out and say it, they suggest it. In this case, immigration is suggested by the aeroplane, the symbol developed by the Far Right of deportations on charter flights, and Africa is suggested by the sun. This was a way for the FN to avoid being taken to court in some instances. The party came up with another speciality, which they covered the whole country with in 2002: tracts printed on metro tickets, false parking tickets, even fake ballot papers, to denounce harassment by the state.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Front national, 2007 (above). This poster, which I picked up at a meeting in 2007, is one of a series of six that were put out for the presidential campaign (see the rest here, presented in a December 2006 video by Marine Le Pen). When it came out, this poster caused such an uproar that it was recalled a few days later. This is the hand of Marine Le Pen [Jean-Marie Le Pen's daughter and successor as party leader] and it represents a radical break with the FN's previous communication strategy. A young Arab woman with a facial piercing, her midriff and the upper seam of her knickers showing (everything the hardcore fringe hates); a grey background far from the usual tricolour hues; the mention of "upward social mobility"; the appearance of a flame (in the logo), which I call the "belly-dancing flame", softer and more feminine than the rigid flame previously used (see ‘spearhead flame' in logo above). The old guard could not stand the sight of this ethnic Arab girl, so a whole wave of FN veterans withdrew from the party in the wake of this campaign.

The Gaullists

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Rassemblement pour la France (RPF), 1948 (above). After the war, republican exuberance waxed triumphant. De Gaulle's RPF "Rally of the French People" co-opted republican attributes and symbols of the French Resistance, of wartime Gaullism and of the French Revolution. The propaganda was handled by award-winning author André Malraux [whom de Gaulle had appointed information minister and who later served as his culture minister]. This poster draws on the whole gamut of French republican themes and symbols: revolt against a backdrop of carmine red (not bright vermillion red); the Marianne [female personification of the French Republic] on the Arc de Triomphe; the RPF emblem, which de Gaulle wears on his jacket as he once wore the Cross of Lorraine (symbol of the Free French Forces during the war); and the cockade of the French Revolution [on Marianne's liberty cap]. The object at the time was to make the RPF a nationwide people's party, and de Gaulle held rallies around the country, speaking directly to French workers.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

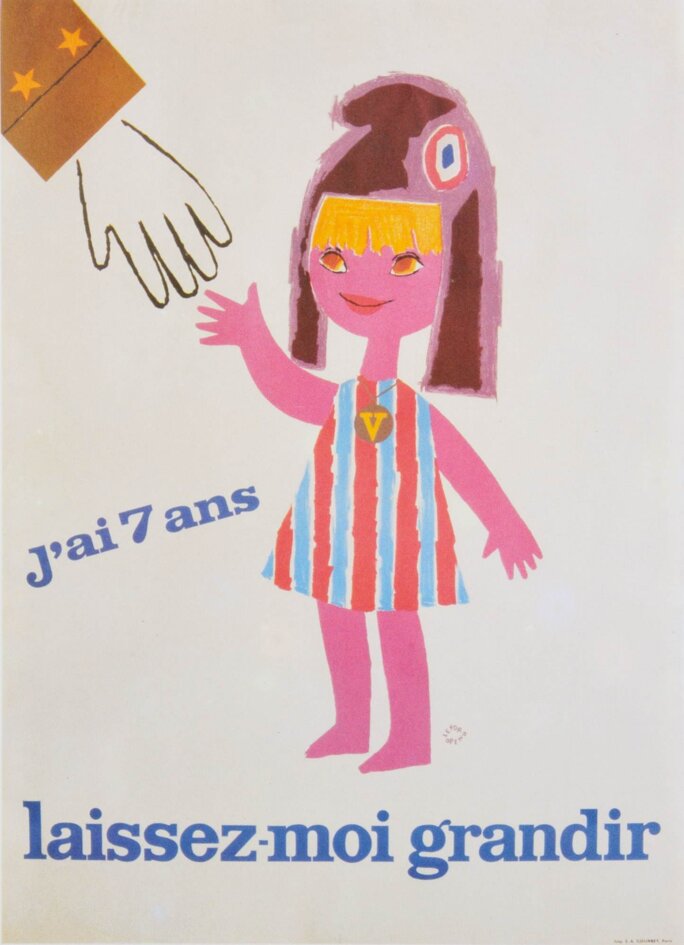

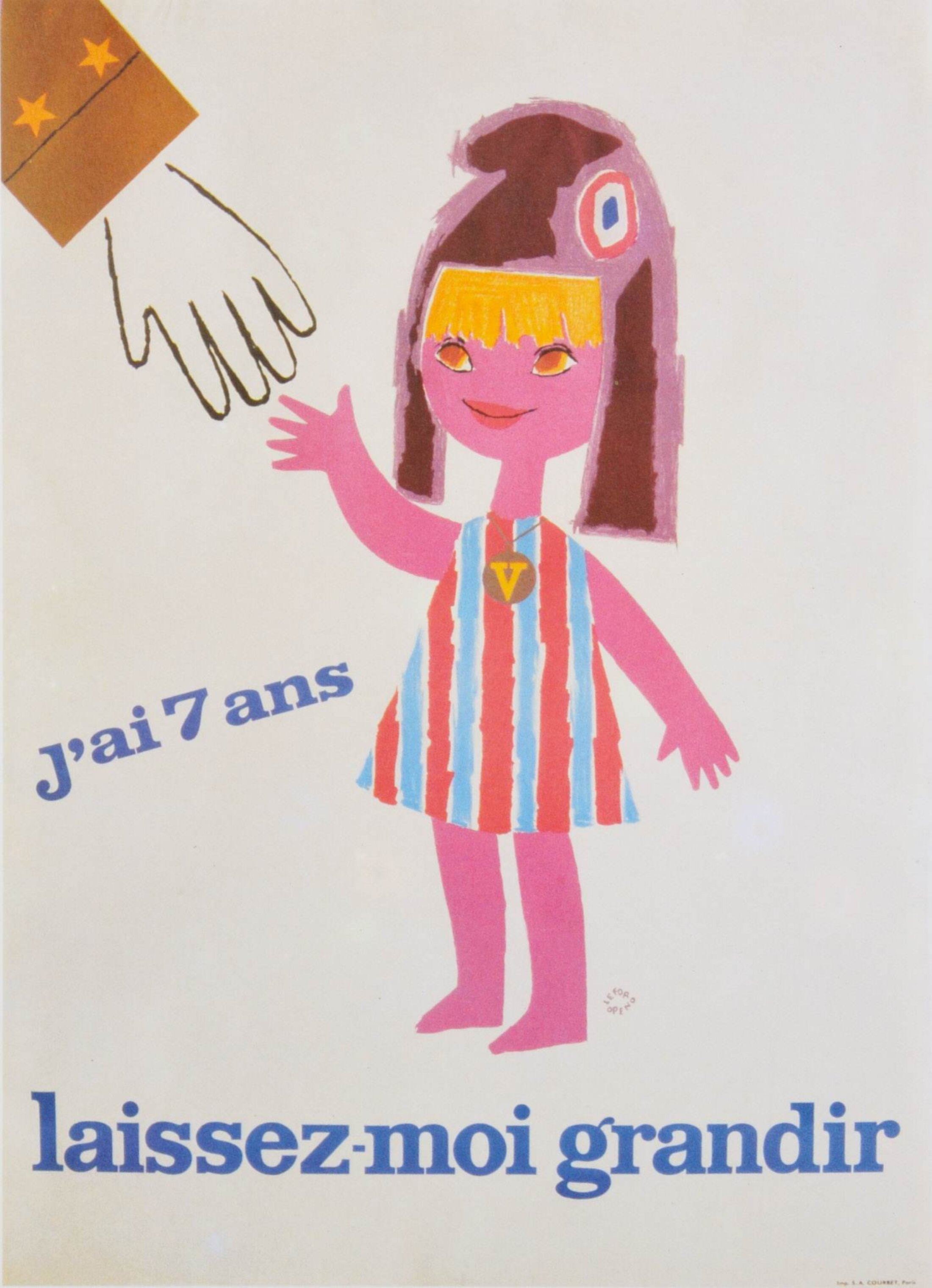

Union pour la Nouvelle République (UNR), 1965 (right). De Gaulle had fought (Algerian War, referendum for direct election of president), he had won, and this poster symbolises another new era. The revolt was over, it was time to reassure the nation. With a seven-year-old baby Marianne, a mascot by Lefor Openon (pseudonym of Marie-Claire Lefort and Marie-Francine Oppeneau, a duo of graphic designers much in demand in the 1960s). De Gaulle has disappeared, but he is suggested by a brigadier general's hand. The little girl is wearing a medallion with the Roman numeral V on it, representing the Fifth Republic, which was also seven years old at the time.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

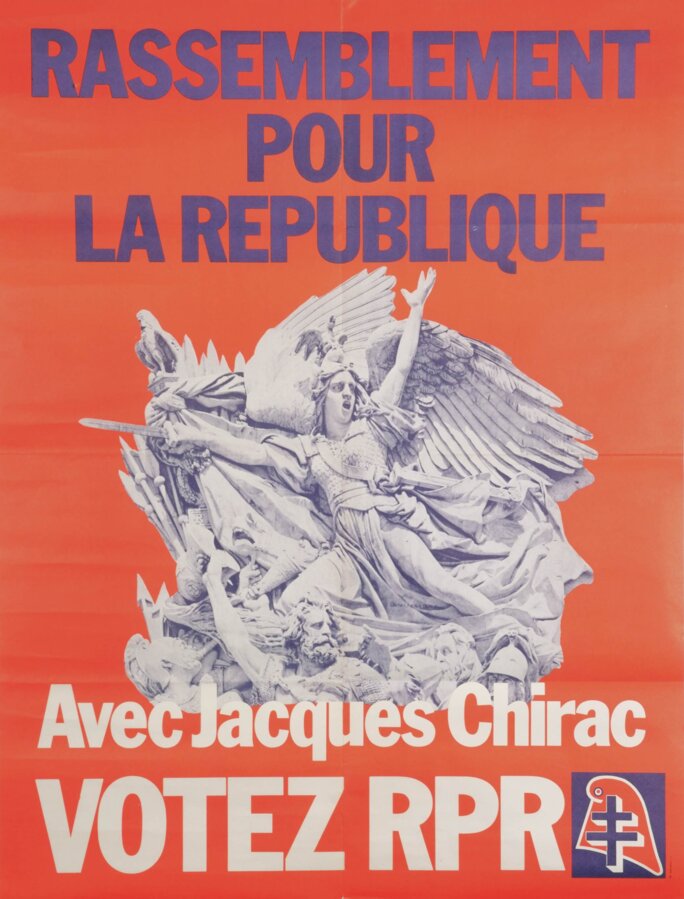

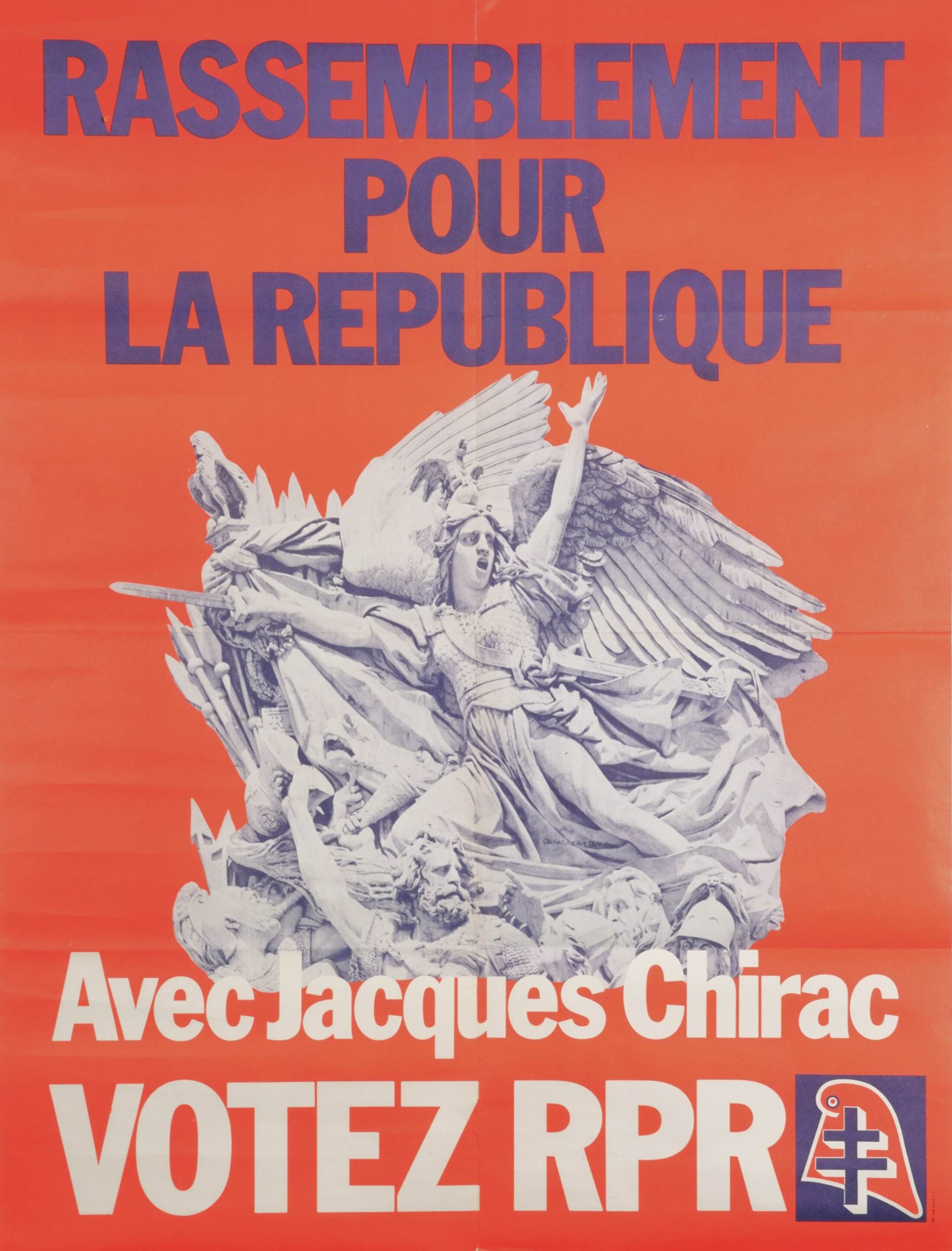

Rassemblement pour la France (RPR), 1976 (above). This poster, which dates from the founding of the RPR, expresses Jacques Chirac's loathing for former President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and his allies. This was Chirac's revenge after being humiliated as Giscard's prime minister [from which post he subsequently resigned]. Giscard had run an American-style campaign (witness the colourful pop visuals of Giscard's post-1968 independent republican movement, Kennedy-style photo ops with his family, an official photo of the president sporting a conspicuous tan, wearing a business suit, and not at the Elysée presidential offices). Chirac countered with this poster, which re-uses Gaullist symbols (the Cross of Lorraine), to say "Stop!" to Giscard's liberal innovations (the right to abortion, reduction of the age of majority from 21 to 18). This is pure populism, harking back to de Gaulle's 1948 revolt by portraying François Rude's sculpture of La Marseillaise in purplish blue against a flashy bright red backdrop.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

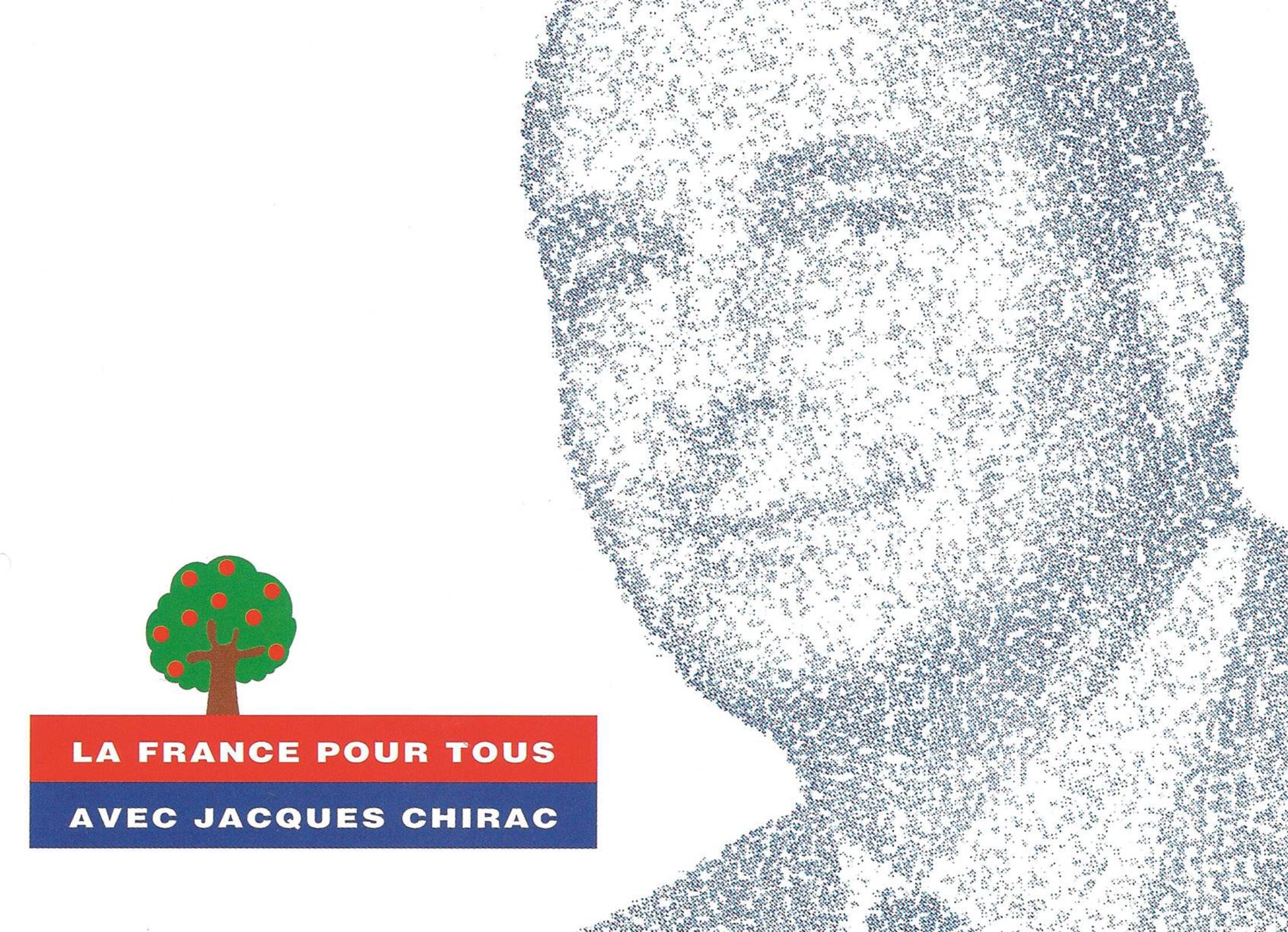

RPR, 1995 (right). Chirac has traded in the Gaullist symbols here for a round apple tree. An idea filched from the logo of Raymond Barre [his successor as prime minister under Giscard d'Estaing] and reworked by Chirac's daughter Claude. This is Chirac all over: populist, simplistic (typical first-grade drawing at school), very neo-Poujadist, and it contrasts sharply with the very highbrow, haughty side of his [presidential election socialist] opponent, Lionel Jospin.

Enlargement : Illustration 11

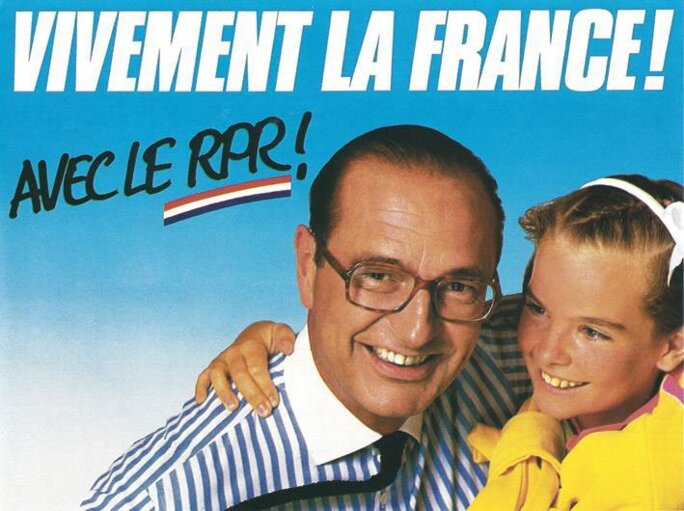

RPR, 1986 (left). A 1985 public opinion poll revealed that 55% of the French preferred ad-speak to political discourse. So during the 1986 general and regional elections, Chirac's party bombarded the country with a four-phase campaign that involved unprecedented spending. After teasers showing a little girl, then a little boy, with the slogan "Vivement demain..." ("Bring on tomorrow"), this poster came out with a beaming Chirac. It was followed by a snapshot of Chirac's circle running in the grass shouting "ouistiti sexe!" [literally "marmoset sex", i.e. the French "Cheese!" for picture-taking purposes] (which was [present-day foreign minister] Alain Juppé's idea). The RPR went on to win the majority in parliament and retake the government.

From the free-marketeers to the anti-Semitics

Enlargement : Illustration 12

Republican Party 1986 (left). This poster was used for the 1986 general elections. It's the American dream. There's something slightly Scientologist about it, a tinge of free-market liberal mysticism. It puts us right smack in the ad-world of the 1980s and '90s. The poster was made by the Havas advertising agency.

Enlargement : Illustration 13

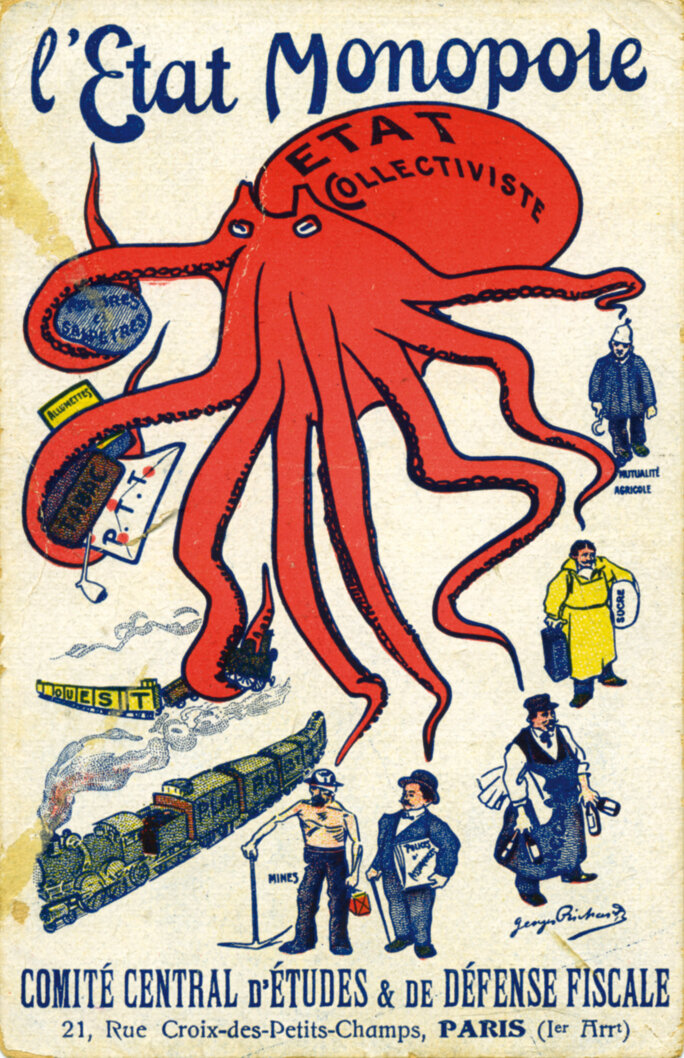

The free-market liberals of the Comité central d'Etudes et de Défense fiscale, 1913 (right). I bought this postcard at a vintage postcards and paper ephemera fair. Back in 1913, the postcard was the pre-eminent medium of print campaigns, as the poster came to be in the 1960s and '70s, and the sticker in the '80s. These moderates, who were lazy in matters of propaganda, took up a recurring theme: the octopus, the sprawling ‘tentacular' state, and behind it the issue of the national debt, the spendthrift state, the costly public utilities. These free-market liberals, who represented the petty bourgeoisie and the middle class, were the precursors of today's UMP [President Sarkozy's ruling French conservative Right party].

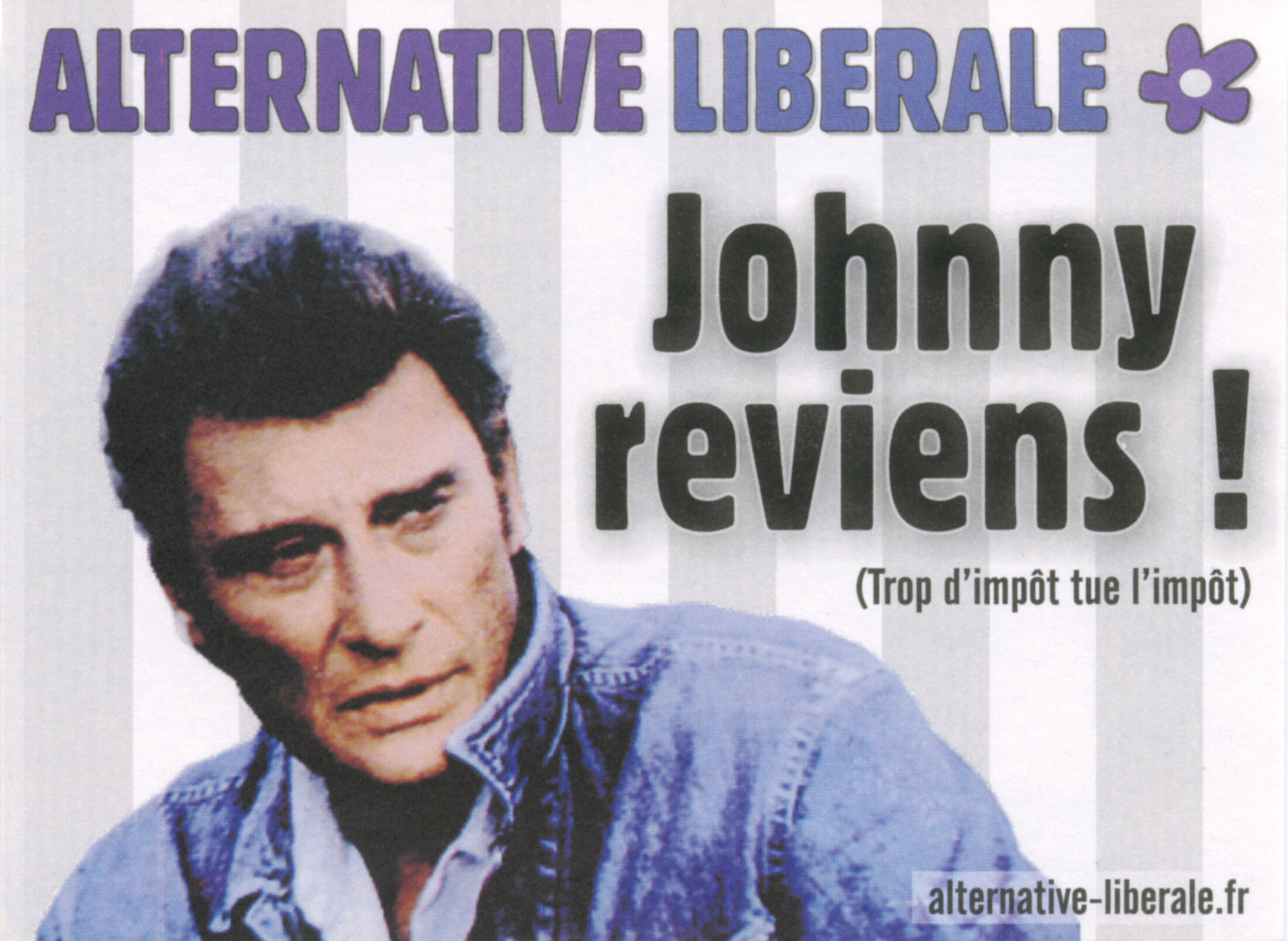

Enlargement : Illustration 14

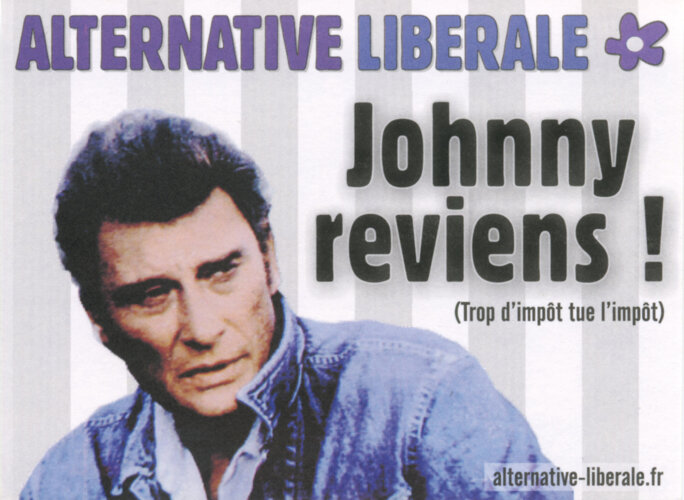

Alternative libérale, 2008 (above). A century later, we find the same theme again: the crusade against the overtaxing state. [French rock star and idol Johnny Halliday was briefly a tax exile]. But with a trace of provocation and non-conformism (surprising colours) here on the part of the liberal ‘young guard': the Liberal Alternative and the Liberal Democratic Party (the latter were the first to feature a national debt clock in their campaign).

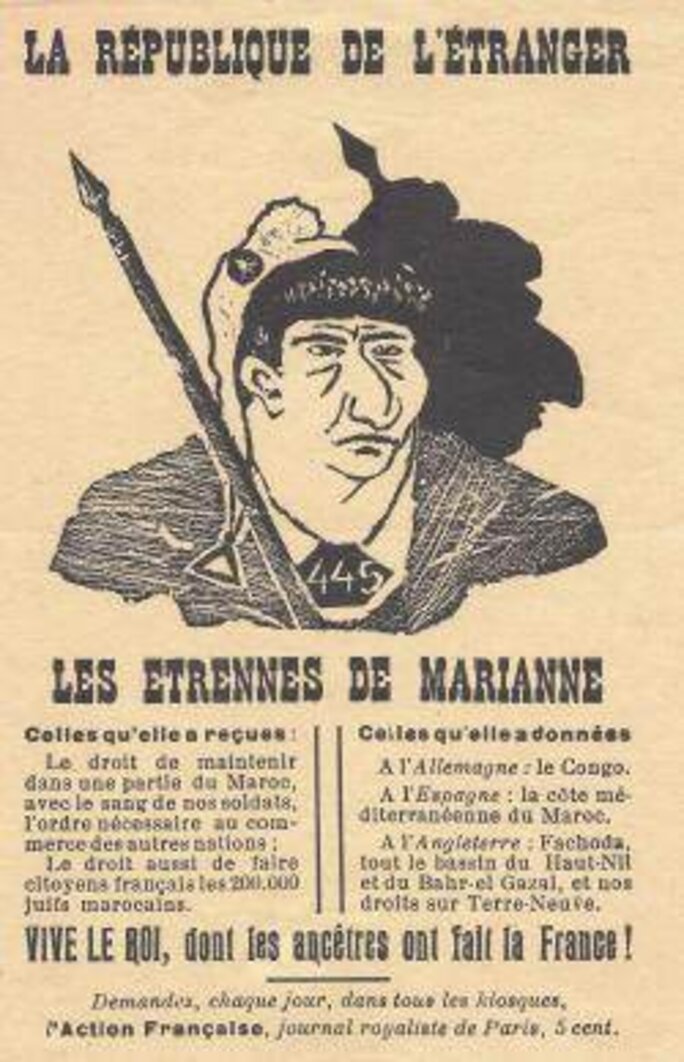

Action française, [Far Right Monarchists] 1912 (left). I acquired this papillon, the precursor of the sticker, through the collectors' society to which I belong. The royalists of Action Française made anti-Semitism, which was the foundation stone of the French Far Right, their stock in trade: it takes up three-quarters of their visuals. Amid the widespread upsurge of anti-Semitism, they equated ‘Jew' with ‘Republic' (note the hook-nosed Marianne). The Jew is the alien, the menace, and the Republic is accused of freeing the Jews.

Enlargement : Illustration 16

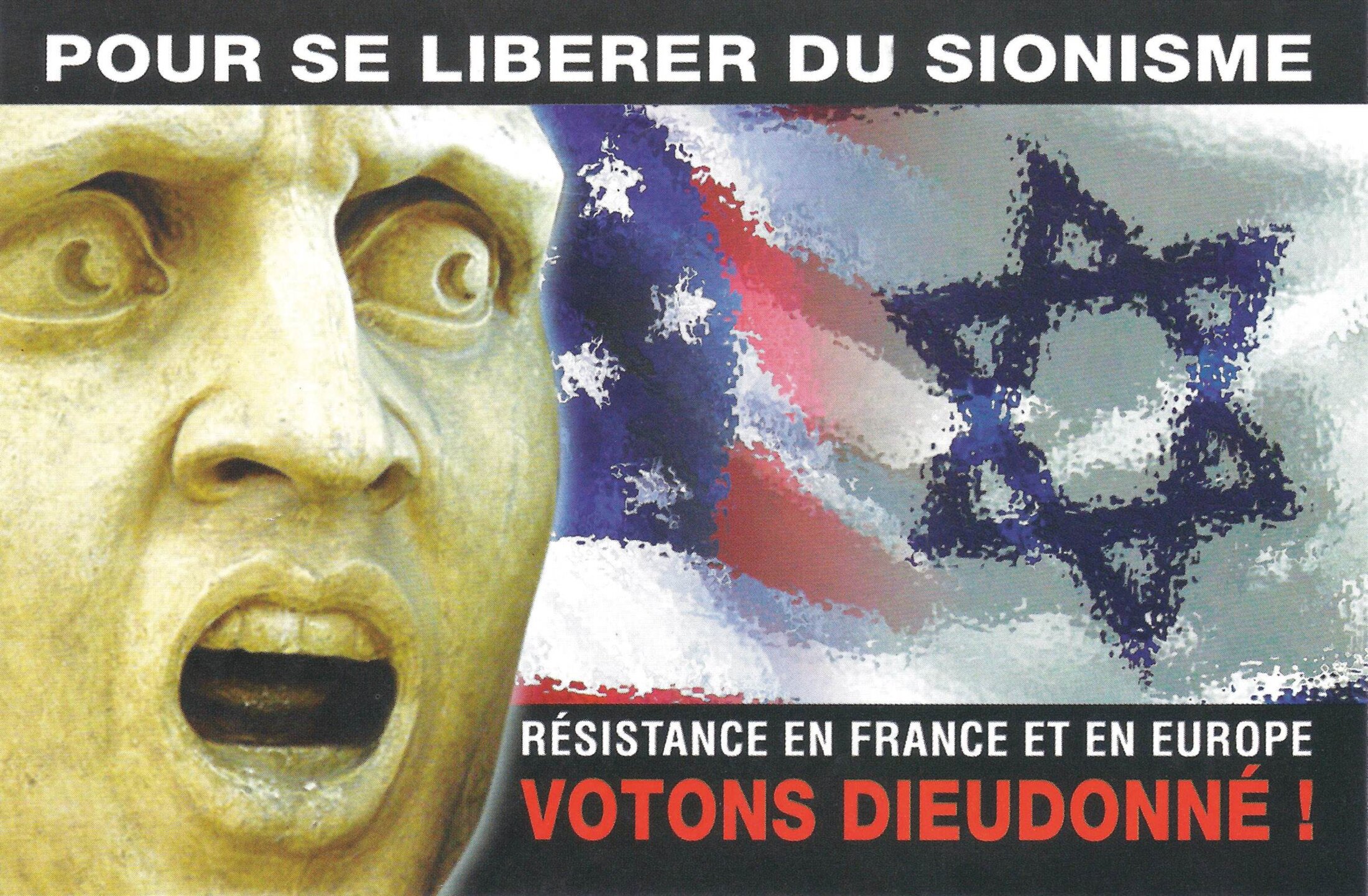

Support Committee for Dieudonné, 2009 (right). This poster marks the return of anti-Semitism in the guise of anti-Zionism. The Jew has become the Zionist, with an American/Zionist plot in the backdrop symbolised by the blending of the two flags. It incorporates part of François Rude's sculpture (Le Génie de la Patrie [aka La Marseillaise]) on the Arc de Triomphe, albeit divested of republican symbols (close-up on the facial expression of hatred, without showing her liberty cap). One can sense the influence of [anti-Zionist polemicist] Alain Soral here.

Enlargement : Illustration 17

Anti-Zionist List, 2009 (left). This was Dieudonné's party ticket for the 2009 elections to the European Parliament. It takes up the theme of European nationalists. Visually, it's a rip-off of the poster for the cult movie Matrix, clearly targeting youths and the poor suburbs. A skilful communication exercise indeed.

“FOR A EUROPE LIBERATED FROM THE CENSORSHIP OF COMMUNITARIANISM OF SPECULATORS AND OF NATO. ANTI-ZIONIST LIST”

Back to the future: the FN and UMP now

Front national de la Jeunesse, November 2011 (above). The latest FNJ [FN youth wing] campaign (already widely subverted on the web) offers a choice between two visions of France: "poverty and crime" or "peace of mind". It calls to mind a series of 62 posters put out by the [WWII collaborationist] Vichy regime to morally educate the population by inculcating precepts of good conduct - particularly, owing to its very tidy aspect, this poster (1943) of a little boy as good as gold, who is told to "look people in the face" ("A French child looks people in the face").

Nowadays the FN opt for a muted shade of blue to ‘grab' people, like the sky blue of Marshal Pétain. Soft shades of blue are intended to mollify people, calling to mind the sky-blue tunics of World War I soldiers and the Marian blue of the Virgin Mary. These posters, which were extremely modern for the period, were executed by a team of the best graphic designers around at the time, known as the Équipe Alain Fournier.

UMP, November 2011 (left). This is an anti-socialist leaflet [three million copies printed, plus five different blue-white-and-red posters, 40,000 copies each, bearing the slogan "Fiers de nos valeurs", meaning ‘Proud of our Values']. This scene-staging with a mass of waving French flags is to be found in FN visuals. But it is unusual for the UMP, I never saw this in Chirac's campaigns.

During the 2007 campaign, Nicolas Sarkozy had already taken up (verbatim) a hard-hitting FN slogan dating from 1988: "Love France or leave it!" [which was then rehashed by the Far Right in 2002]. Sarkozy never writes such hard-hitting slogans, they are spoken. Therefore no written trace or documents with this kind of phraseology are found.

- 'Tricolores: une histoire visuelle de la droite et de l'extrême droite' is published in France by Éditions l'Echappée, priced 29 euros.

-------------------------

This English version of an article originally published on Mediapart's French pages is by Eric Rosencrantz.

(Editing by Graham Tearse)