At ArcelorMittal’s quarterly results meeting on May 10th, Lakshmi Mittal, chairman and CEO of the steel conglomerate, caused some surprise when he argued that Europe needed to introduce protectionist measures. Mittal, known as an advocate of unfettered free trade and globalisation, sounded curiously like his arch-enemy Arnaud Montebourg, the socialist industry minister (Minister for Industrial Renewal) whom Mittal had called an economic dinosaur just a few months earlier.

The 62 year-old London-based steel tycoon announced a 345-million-dollar loss for the first quarter of 2013, then launched into a spirited defence of European industry. "There should be increased tariffs for imports, or there should be a surcharge on the steel coming to Europe from countries where environmental standards are very low," he said. Mittal also criticised austerity policies across Europe, adding: "They [policy makers] have to save European manufacturing, whatever you may call it, what I want is actions to save the domestic manufacturing, including steel."

Yet until now Mittal had been a fervent opponent of any restriction on the free movement of goods and services, and for a very good reason: his group benefits hugely from the system, liberally importing low-cost semi-finished steel products like hot rolled coils and billets that it manufactures in its blast furnaces in Indonesia and India, and selling the finished products in Europe.

But even the firmest convictions can be shaken by five years of economic crisis. The European steel industry, which has been to the brink many times before, is once again on the verge of collapse. Just as its traditional outlets are drying up, in particular in the car industry, tonnes (metric) of cut-price steel from China or elsewhere are flooding its market and creating over-capacity.

Steel makers have been saying that, at the very least, the European Union should copy the American approach. The United States has sought to protect its steel industry by applying hefty surtaxes to steel imports in times of crisis, sometimes as high as 200%. But so far the European authorities have refused to take any protective measures in favour of the steel industry, invoking the principle of free and fair competition.

What is perhaps most revealing here is Mittal’s sudden interest in Europe. The ArcelorMittal chairman has always portrayed his group as worldwide and globalised. Europe has been regarded as a rather unimportant part of this global empire, far less significant in any case than emerging economies or the US, where, according to neo-liberalism, it is all happening.

So why this abrupt volte-face, and why suddenly seek support from the European authorities? Because despite everything, ArcelorMittal remains a viscerally European company. Europe has given it a great deal and is still key for the preservation of the company’s fortune.

For Mittal himself would never have become a billionaire without Europe. The saga began back in the early 1990s, when Eastern Europe’s economies were collapsing after the fall of the Berlin Wall. At the time, the sycophants of shock therapy embraced total privatisation and were selling off everything they could. Mittal was already living in London but was still an unknown figure.

He went cap in hand to banks in the City of London as well as to Goldman Sachs, seeking to buy up choice morsels of the former Eastern Bloc’s steel industry. He was interested in everything and became an important figure for the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (ERBD), which was spearheading Eastern Europe’s redevelopment.

These lofty institutions even put pressure on governments to re-draft their privatisation laws, as that exercised on Prague so that Mittal could get his hands on certain Czech steel plants. They also turned a blind eye to accusations his company was involved in corruption, as in Kazakhstan.

By 2012, Arcelor Mittal paid no tax in Western Europe

At the time, Mittal had plentiful backing from banks and international institutions. Europe granted him an avalanche of credits to help him restructure the Eastern Bloc’s steel industry. From there he moved on to Western Europe, buying up sites that European steel companies deemed to be no longer productive, like that of French steel-maker Usinor at Gandrange, in the Lorraine region of eastern France, in 1999. And again Brussels backed him and granted credits to his conglomerate, which now had a European ‘passport’ with its legal headquarters in the Netherlands - even though it was controlled from a tax haven in the Dutch West Indies.

Mittal pursued his strategy of conquest with his 2005 purchase of International Steel Group, composed of three US steel makers, including Bethlehem Steel which had filed for bankruptcy in 2001. But soon his debt levels became unsustainable. In a move to restore balance, and backed by Goldman Sachs, he embarked on a hostile bid for Luxembourg-based Arcelor which he clinched in 2006.

Arcelor had been formed in 2002 from the merger of three European steel firms: Spain's Aceralia, Belgium's Arbed and France's Usinor. France, which had spent over 100 billion French francs - or 15.25 billion euros – trying to save its steel industry, had not kept a stake in Arcelor and had to watch from the sidelines as Mittal did his deal.

Luxembourg, however, was still a shareholder and was able to negotiate that the headquarters of the new entity would remain on its territory. It had hoped that this, plus its flexible tax regime, would make the country a natural transit point for Mittal Group's financial transactions in Europe, or even worldwide. But it was not to be.

For Mittal gave nothing to Europe in return. The company has hardly paid any tax on the continent since 2008. It posted a profit of 2.9 billion dollars in 2010, out of which it claims to have paid 817 million dollars to the Belgian tax authorities – a figure contested by Belgian press reports which say ArcelorMittal has not paid tax in Belgium since 2008 – and 52 million dollars in France.

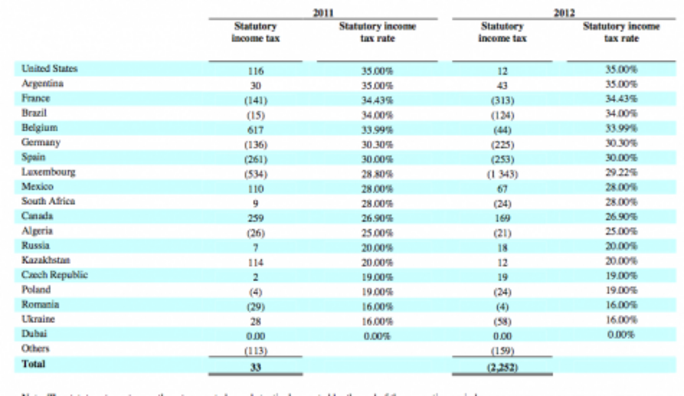

Elsewhere in the European Union – Germany, Spain and Luxembourg – it benefits from tax credits, sometimes for astronomical amounts, such as a 2.2-billion-dollar tax credit in Luxembourg in 2010. By 2012, ArcelorMittal paid no more tax in Western Europe. On the contrary, its tax position showed a combined total of 2.1 billion dollars in credits in Luxembourg, France, Germany, Spain and Belgium.

In Eastern Europe it has paid tax on its profits only in Russia, Kazakhstan and the Czech Republic, for a total of 49 million dollars. And in all remaining European countries its tax position is in credit. The entire ArcelorMittal group claims to dispose of a total tax credit of 2.2 billion dollars.

The economic crisis has of course hit businesses across the board. In 2012 ArcelorMittal depreciated its European assets by 4.3 billion dollars in its accounts, in line with accounting standards set out by the IFRS. And it is still carrying forward losses accumulated during the long, hard restructuring of the European steel industry.

But these are not the only explanations for ArcelorMittal’s tax situation. According to its own accounts, ArcelorMittal's European business has never made profits, not even during the steel price surge in 2008. Yet Arcelor was considered the top global steel company before it was taken over by Mittal, one well positioned in the most promising, highest added-value segments of the market, with a high level of research to boot. In 2006, a poor year for cyclical steel prices, it had nevertheless managed to make a profit of over 2 billion euros.

Vertical integration riddle

The key to the puzzle lies in the obscure way ArcelorMittal has been structured since the merger. As the bourse battle unfolded in 2006, no one really paid attention to the details of what Lakshmi Mittal was saying, yet these were essential. In essence, he described a new organisation that would be opaque and secretive.

After the merger, he explained, ArcelorMittal would no longer function in business units and geographical centres, but would be vertically integrated from the mines to finished steel products and sales. This would mean the group could benefit more from its huge capacity, juggling between its various businesses and plants depending on market opportunities. All its sites would be grouped together, making it impossible to distinguish between them.

Mittal's son, Aditya Mittal, was appointed financial director for the group and the flat steel business in Europe, and a handful of Indian managers were brought in to help him run the group. This small committee became the only body to access all the group’s figures, to understand the reality of the business and to organise transfers of production from one part of the world to another.

ArcelorMittal employees were to feel the change in culture immediately. Previous management had instituted a flow of information to employees in the wake of the bloodletting the firm had endured during the industry's harsh restructuring. The aim was to win their loyalty to rebuilding the group, to avoid disputes escalating and to keep them better informed on future directions. Suddenly, the dialogue ceased.

All information, besides health and safety criteria, disappeared. Employees are simply expected to trust in the wisdom of their management. Not a single site has any knowledge about its own performance, production, costs, sales prices or clients. Analytical comparison, a major tool in industrial management, appears to have gone out of the window.

The group centralises everything on a system of vertical integration. Some 60% of coal and 15% of iron ore are supplied by mines that are either entirely owned or part-owned by the Mittal family, and supplies are transported, in part, by ArcelorMittal’s own fleet of merchant ships registered in London.

“Vertical integration has no impact on the accounting which is established according to IFRS standards, nor indeed on the accounts established under French standards and other compliances required by law,” the group said in a written statement in response to questions from Mediapart. Nevertheless, it is ArcelorMittal which determines the delivery price of supplies and services. In its annual report, the group indicates simply that the costs of supplies of coal and iron ore are calculated according to international market prices.

But it remains unclear whether this is the true price, and whether certain arrangements are made in one direction or another. ArcelorMittal offers no information on this. If the costs are indeed indexed to international markets, this raises a question over the group's practice of vertical integration which would usually be supposed to ensure, from one end of the chain to the other, a certain protection from the economic upsets that can have a knock-on effect on mining, at the bottom end, and steel production, at the top. What is the purpose of vertical integration if it brings no beneficial effect and exposes the group to the ups and downs of markets?

'Accounts do not correspond with IFRS standards'

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Following the closure of the two blast furnaces of ArcelorMittal’s plant in Liège, along with its hot phase and seven finishing lines, Belgian trades unions received the support of the Walloon (French-speaking region) government in their attempts earlier this year to gain access to details of the plant’s finances, with a view to finding a buyer for the site. But the group provided only bits of information which, for example, did not include details of the flow of supplies between Liège and other sites.

“The Mittal company is not doing very well and the manipulation of information is used here as a weapon,” commented Didier Van Caillie, a professor of industrial strategy at the school of higher studies, HEC Liège, in an interview with Belgian daily la Libre Belgique. He said the group was “virtually incapable of having an objective view of its economic reality”.

“It was built up very rapidly by mergers and takeovers of companies that had very different accounting systems, which Mittal has kept,” added Van Caillie. “That is in fact its major weakness, which prevents the group from facing up to the crisis. Even if they wanted to, they would be incapable of supplying more precise figures. The information is manipulated and can therefore show any site to be a good or bad performer.”

The same thing happened at ArcelorMittal’s steel mill in Florange, north-east France, when management was incapable of supplying reliable figures about the site to the French government and trades unions. The group had much to say about the costs of renovating the plant’s blast furnaces, and of European over-supply of steel, but it never detailed the economic reality of Florange. Questioned by a French parliamentary commission, Lakshmi Mittal referred to exorbitant welfare contribution payments that bumped up employment costs, but once again offered no precise figures.

Similarly, the group declined to answer Mediapart’s request for details of the projects that were the subject of its 2 billion euros of investment in France – a figure cited by Mittal to the parliamentary commission. The only trace of investment by the group in France that Mediapart could find independently is the renovation of the blast furnaces of the ArcellorMittal plants in Fos and Dunkirk in northern France.

The group’s European employees have no means of knowing whether their particular site is competitive or not, nor whether and where these may require improvements. They live amid unstable conditions, under threat that the group could announce overnight the closure of one site or another without any possibility of challenging the reasons given. For ArcelorMittal, the sites are simply centres of cost, as defined arbitrarily at the highest levels of management, and rarely sites of profit. Tax breaks, public aid for research and other subsidies are never properly accounted for.

As the trades union representatives at the Florange plant discovered, the sites never receive pro rata payments linked to CO2 quotas. According to a report by the French Ministry for Sustainable Development, dated February 2010, the Florange plant “having announced the prolongation of its activities at least until 2012” was allowed production of an extra 800,000 metric tonnes of CO2. At the time, the market price of a tonne of carbon was about 13 euros, which meant the total represented a value of 10 million euros. Thus, with the launching of the shut-down of Florange’s blast furnaces in April 2011, ArcelorMittal had, over one and a half years, an annual allowance of 4.8 million tonnes of carbon for a site that hardly produced any CO2.

Between 2011 and 2012, ArcelorMittal capitalized nearly seven million tonnes in carbon credits for Florange alone, according to research company Carbon Market Data, whose findings are based on European Commission figures. Taking the average carbon pricing over the past two years, that represents more than 64 million euros.

But none of this appears in the site’s accounts, nor even in the group’s accounts for its French operations. All carbon credit transactions are centralised with the Luxembourg-based holding company, but never reattributed. In 2012, ArcelorMittal sold 21.8 million tonnes-worth of CO2 certificates for 220 million dollars. Today, however, the price of carbon credits is at around 5 euros per tonne, and the group has announced that it will in future hold on to its European carbon credits.

More troubling still are the group’s commercial practices. Part of its sales operations is centralised and appears in the bookkeeping of its Luxembourg holding. In its annual report, the group is careful to break out, below its gross margin, a line for sales expenses, holding company costs and those of shared services. Depending upon the year, these amount to between 3 billion euros and 5 billion euros. For French chartered accountant and statutory auditor René Ricol, a former advisor to the French government, these do not correspond with IFRS accountancy standards. “If there are marketing costs, these are usually accounted for in the normal operating costs,” he said.

ArcelorMittal did not respond to Mediapart’s request for details about these costs and the reason that they are accounted for separately.

In its filings to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the group indicated that holding company charges and those of shared services amounted to 265 million dollars in 2011, and 158 million dollars in 2012. There is no mention of what these costs relate to, nor who benefits from them, nor the remaining sales costs amounting to around 3 billion dollars.

According to Mediapart sources, ArcelorMittal has put in place a system whereby each of its subsidiaries and sites pay a contribution to marketing costs, and which, for the period 2008-2009, reportedly amounted to 14 euros per tonne of steel sold.

How can a group receive payment for a percentage of each tonne sold and who benefits from this? In 2007, a dispute erupted between the tax authorities of Kazakhstan and ArcelorMittal’s subsidiary in the country, which was accused of using the system in its coal mines for the purposes of tax evasion and of paying no company taxes. An audit of the subsidiary, Mittal Steel Temirtau, revealed that the company sold most of its steel exports via a foreign-registered company, using fixed prices that ignored the fluctuations of the international market. The Kazakh authorities eventually reached an agreement with Mittal.

ArcelorMittal did not reply to Mediapart’s questions about the existence of a levy system for marketing costs. If such a system exists, it would be easier to understand why the group’s European sites never pay taxes, for part of the operational margin can be transferred. If so, this raises the question, to where?

Beating Luxembourg at its own game

Because ArcelorMittal’s activities in Luxembourg are not considered to be those of production, all its commercial transactions registered in the Grand Duchy are described as relating to exports. Thus the group, which considers its base there as a commercial hub, pays no VAT or similar charges. Furthermore, the holding company’s consolidated losses result in the group paying no company tax. The Luxembourg authorities receive only a payment of 15% of the value of paid dividends.

“One can understand why Luxembourg agreed to join other European countries in reflecting upon the future of the European steel industry and ArcelorMittal,” commented one well-informed source. “It had believed it would be a beneficiary of the Mittal system. In the end, it has lost as much as the others.”

Taking advantage of the current competition between European countries regarding tax incentives, ArcelorMittal set up one of its financial centres in Belgium rather than Luxembourg. ArcelorMittal Finance and Services Belgium SA benefits from a tax break system unique to Belgium called the ‘notional interest deduction’, or NID. As a Belgian government introduction to the scheme explains, it allows “all companies subject to Belgian corporate tax to deduct from their taxable income a fictitious interest calculated on the basis of their shareholder’s equity (net assets)”.

ArcelorMittal has placed in Belgium most of its generated cash, which reached a total of 46 billion euros. According to Belgian press reports, the group was the foremost beneficiary of the NID scheme in 2009, when it deducted 1.28 billion euros from its tax returns - leaving it liable to pay just 496 euros. In 2011, ArcelorMittal deducted 1.5 billion euros under the NID scheme.

According to a study by the far-left Belgian Workers’ Party, the PTB, the group’s financial branch made a profit of 5.8 billion euros between 2008 and 2011, while during the same period it deducted 5.6 billion euros from its tax returns under the terms of NID. It paid taxes only in the year 2008, as it set up its Belgian base, and which totalled 81 million euros.

Amid increasing public criticism of the NID scheme, the Belgian government announced it is to review of the conditions of the tax break. In October 2012, ArcelorMittal transferred 37 billion euros from its Belgium-based unit - leaving it with just more than 1 billion euros. According to the group’s official explanation, the sum was transferred to Luxembourg.

- In the second and final part to come of this investigation, Martine Orange reports on how ArcellorMittal has now planted its financial arm in the tax desert of Dubai, and reveals the curious network of tax-haven companies via which the Mittal family controls the group.

-------------------------

English version by Sue Landau and Graham Tearse

(Editing by Graham Tearse)