Olivier Roy is a recognised expert in France and abroad on questions of Islam and religious fundamentalism, the author of numerous works, including Globalized Islam, published in English by Chicago University Press. A senior researcher for the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and a former consultant to the UN and visiting Professor at Berkeley University, he is also chair of Mediterranean studies at the European University Institute based in Florence, Italy.

-------------------------

Mediapart: You dismiss the comparison that has been made by some between the recent terror attacks in Paris and the 9/11 attacks in the US in 2001.

Olivier Roy: Yes, in terms of intensity they seem to me different all the same. In New York, there were 3,000 dead, a very carefully prepared operation directed from abroad. It was the launch of al-Qaeda which had moved on to [becoming] a global strategic threat. Here, in France, we have crimes committed by three little wankers who have learnt in the Yemen how to handle a Kalashnikov. The symbolic and emotional impact is considerable, but in terms of security or geostrategics, we’re not in the same dimension.

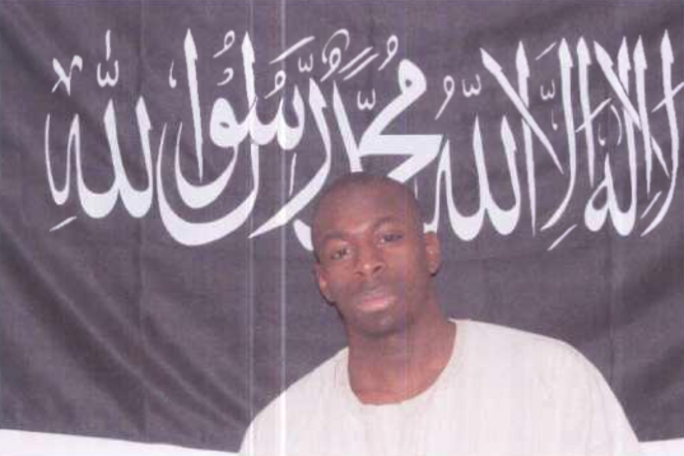

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Furthermore, I am a bit surprised at the intensity of this symbolic and emotional impact, whereas there’s not much difference with the killings carried out by Mohamed Merah, which didn’t have the same resonance. There is here an overflowing of affection which seems to me indicative of a profound malaise.

France has known several terrorist attacks which didn’t spark such a degree of panic, nor this appeal for national unity which seems to me to be the reflection of a false unanimity. If there is unity, why reject the [far-right party] Front National from the [January 11th mass anti-terrorist] demonstration, and if there is not unity why go about things as if the divisions and differences of opinion had suddenly disappeared? The latter will come back with so much more force because they were masked by the new ‘politically correct’.

The homage to the victims is indispensable and the compassion is necessary, but I don’t understand why there is almost no word about the [four] victims [of shootings at a kosher store in Paris the suburb] of Vincennes with regard to such a mobilisation around Charlie Hebdo, which was, par excellence, a very insolent magazine, dissenting, capable of laughing at everything, which abhorred artificial unanimity.

It’s as if at each terror attack there were ‘true’ victims and collateral victims. Now, if Charlie Hebdo was targeted for what it was, one can presume that [the gunman at the kosher store] did not enter a Jewish establishment by accident. Also, I can’t help myself from feeling there is a sort of corporate self-pitying on the part of a section of the media which seems to me very far from the spirit of Charlie.

Mediapart: Is anti-Semitism an integral part of the jihad?

O.R.: Anti-semitism is not an integral part of the strategy of the jihad leaderships. Neither [the late al-Qaeda leader Osmama] Bin Laden, nor [Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-] Baghdadi made Jews their principle target. For them, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not the key element of every conflict. The enemy for the former is the West and, for the latter, ‘the heretics’, meaning the Shiites. On the other hand, for the young, radical Islamists mobilised in the West, anti-Semitism is a fundamental dimension, but which is part of a culture shared with quite a few others.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Indeed, this latent anti-Semitism is not specific to young Beurs [the common, non-pejorative French name, derived from slang, for French youths of families of North African origins] in the [run-down, high-rise] suburbs. You only have to look at the followers of [anti-Semitic essayist, Alain] Soral or [anti-Semitic provocateur and stand-up comic] Dieudonné. With no Muslim reference, they distil an anti-Semitism that has an impact on a youth that feels marginalised, whatever its religious references.

We make of Islam a line of division in France, without seeing all that is shared by the ones and the others, and all that is transversal in these forms of violence and in anti-Semitism, which is not specific to young Muslims. You only have to look at the commentaries of readers on newspaper websites and on blogs to realise this.

Mediapart: Chérif Kouachi was apparently involved in trying to spring from jail Smaïn Aït Ali Belkacem, the convicted bomb-maker for the murderous 1995 terror attacks in Paris committed by the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria. Is there a jihadist continuum since the 1990s?

O.R.: Yes, I don’t believe in these stories about first-, second- or third-generation jihadists. A new generation is invented as soon as we don’t understand what’s going on. So there exists a continuity, in the permanence of figures like [convicted Islamist terrorist, Djamel] Beghal, or in the transmission [of jihadist indoctrination], which is notably carried out in prison. It’s like the world of gangsters – there are mythical figures, a transmission, myth-making of the elders, reinforced by the pedagogic role of prison.

This continuity does not signify that there is not an evolution. I think that this evolution is less about the number of those converted, which according to me is at a constant level that we’re only recognising today – the Beghal group already contained about a third who were converts – but more about the increasing importance of women. Consequently, the jihad is now carried out more and more by families, between brothers, or with women and children, whether that be in France or departing for Syria.

Mediapart: How are youngsters drawn to this murderous ideology?

O.R.: My theory is that the principle reason for this radicalisation is the crossing together of, on the one hand, Muslim references, and on the other a culture of violence, of resentment, of nihilistic fascination for an unhealthy heroism, negative and suicidal, that of the young killers of [the 1999] Columbine [High School killings], who massacre people of their school and stage themselves in online videos before committing their acts and dying, because death is always the end of the story, and which was the also the case for the [1970s German terrorist] Baader group.

The globalised jihad is practically the only worldwide ideology available on the market today, in the same way that revolution was the standard ideology of unhinged youngsters in the 1970s. By placing the accent principally upon eventual sources of violence from the Koran – a Koran that the Westernised youngsters often have as little knowledge of as their little or non-grasp of Arabic – we simply ignore the profound continuity of Islamic terrorismwith this young culture of violence and the fantasy of the all-powerful, that of the Clumbine effect in the United Sates, that which explains the success of films like Scarface in the [high-rise, lower working class] suburbs, not to mention video games or Natural Born Killers.

What I’m about to say should be taken with precaution, but I find the example of [the southern French city of] Marseille interesting. Marseille has never played a part in political radicalisation. In the 1970s, the [1960s-70s French Maoist group] la Gauche Prolétarienne, and the [1980s French far-left terrorist group] Action Directe were not represented in Marseille, and today Islamic radicalism hardly exists either. Whereas these radical Left groups of the 1970s and 1980s were, like radical Islam today, are over-represented in Grenoble, Lyon, Lille and Paris. My hypothesis is that Marseille and its culture of local violence and gangsters offer a door to this culture of violence, which doesn’t need to pass through political radicalisation; The young gangsters in Marseille are in the same stage setting of spectacular violence, in this culture of the super-man, but don’t give themselves the right to [decide the] life or death of anyone and everyone.

But when you question the mothers of gangsters and jihadists, you see they are all appalled at the delinquent or religious radicalization of their children, which have something in common. In fact many jihadists are former delinquents. They don’t understand why, when they tell their sons that they are going to die, it doesn’t stop them. But these youngsters are fascinated by the all-powerful and the cult of the super-man. They know they’re going to die, but they don’t care. We’re in the same case as [French gangster Jacques] Mesrine, even if he wasn’t a mass killer. And we move from the culture of the revolver to the culture of the Kalashnikov, which does more damage.

Mediapart: Chérif Kouachi appears to have been previously involved with fundamentalist religious groups. Does that weaken the distinction between Salafist Islam and radical Islam that is turned towards the jihad?

O.R.: Lots of young jihadists have passed through fundamentalist groups, the Tablighi and above all the Salafists. But I think one should understand that to be like the direction of youngsters who are trying to find themselves, who dapple with delinquency, with Tablighi, with Salafism, in order to find their path.

In a true Tablighi or Salafist group, you have a discipline that they often have difficulty in adopting, with wake-up at five o’clock in the morning, religious predication, the internal regulations of a group. Young jihadists often pass through fundamentalist groups but, most of the time, don’t remain within them for very long. If they stay in the group, they get older and calm down. There is hardly any example of people who spend ten years in a Salafist group before embarking on jihad.

In the same manner, lots of youngsters who join a training camp come back quickly because they can’t stand the discipline. It is clear that the Kouachi brothers had military training, but I am not certain that they were part of an armed and structured unit. The manner in which they escaped and the fact that they left an identity card, like a strong Freudian slip, the will to personally sign their acts, resembles more the gestures of wandering radicalised individuals rather than those of professional militants hardened by experience.

Mediapart: Shortly after the attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices you wrote an op-ed article in French daily Le Monde in which you said that this act of terrorism transforms an intellectual debate into a quasi-existential question, that to question the link between Islam and terrorism leads to the question of what place Muslims have in France. In what way is that so?

O.R.: Today, even anti-racists ask themselves ‘is there not something in Islam that leads to these sorts of massacres? Until now, this question was limited to certain ideological poles, the anti-immigration populists, the anti-Islam right-wing identity movement, and even a fringe of militant secularists. Now this idea has become a cliché and this type of argument has found freedom, notably since the debate about national identity launched by [former French president Nicolas] Sarkozy. It has become the new politically correct [view], even if some publications like Causeur continue to claim that they break taboos and the politically-correct by setting out this type of question.

Now, every essentialist argument is founded on no sociological reality, but valorises a theological reading which is simply the adding together of a few caricatures about the nature of Islam – ‘in Islam there is no separation between religion and politics’ – borrowed, precisely, either from the fundamentalists themselves, or from a bygone orientalism. There is no interest in real Islam, that is to say the religiousness and the concrete practice of believers, in their diversity.

Then also, as usual, there is a constant mixing of ‘ethnicity’ and ‘religion’, while also being incapable of corrrectly defining the one or the other. The confusion is well illustrated in the debate over ‘ethnic statistics’. Instead of it being, let’s say, a scientific debate, which it is all the same for true demographers, it has become ideological and normative. Between those who accuse the progressives of refusing to recognise facts, such as the over-representation of youngsters of Muslim origin in prisons, and these same progressives who warn against the stigmatization of populations of immigrant origins, it is difficult to ask the true questions. What makes up the purely religious, cultural, social and –the grand absent in the debate – political? This same political issue that our politicians hide behind rhetoric and the great communications [business] which is on full-steam during the management of the mourning of the Charlie Hebdo dead.

France is quite more mixed and quite less ethnically separated than is said. When the geographer Christophe Guilluy compares in opposition the close [high-rise, lower working class, urban] suburbs populated by young Muslims – the Muslims are always young, and vice versa – with the peripheral zones of detached homes populated by ordinary whites, he forgets that the latter include numerous families of Muslim origin who have taken part in social ascension and who find themselves in ghettos of the small detached-housing zones.

This blindness also comes from the refusal to see the presence of Muslim middle classes in our society, partly because they don’t want to be seen. But the rise of these middle classes is flagrant. You don’t need ethnic statistics to look up a phone book and to see the number of doctors with an Arab name in middle-sized towns, to consult the list of teachers in a provincial secondary school, or the number of financial advisors in a bank branch in a west Paris suburb.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

These people don’t want to be placed in a community, and don’t want to talk in the name of a community. However, they are ceaselessly associated with problem neighbourhoods. In a town like Dreux [west of Paris], which I know well, the mayors, of Left and right, have for a long time systematically placed the municipal councillor of Arab origin in charge of sport or neighbourhoods – that’s changed.

The community-making machine springs from the manner in which the [French] republic reduces these Muslim middle classes into roles of [watchful and responsible] ‘elder brother’, all the while keeping at arm’s length institutions supposedly representative of Islam in france, which come from abroad and which don’t represent this rising, integrated middle class.

Here and there ‘moderate imams’ are fished out to dissuade youngsters from the jihad, imams who speak only little French, like Hassen Chalghoumi, the imam in [north Paris suburb] Drancy. While the young radicalized jihadists speak in better French are little likely to follow that kind of sermon. We also ignore the real moderates who live tranquilly, without looking for the microphone that is constantly held out in pseudo-reports in the [high-rise, low-income] suburbs.

But there exists no serious work, neither political, nor journalistic, nor sociological, about the Muslim middle classes. The only representatives that we see of these middle classes are women politicians, like [education minister] Vallaud-Belkacem, [former junior minister, Jeannette] Bougrab [companion of Charlie Hebdo editor Charb who was shot dead last week], or [former justice minister, Rachida] Dati, about whom it is ceaselessly underlined that they are exceptions, because they’re women.

Why do you argue that there is no such thing as a ‘Muslim community’ in France?

It’s a fact. There does not exist a religious community founded upon Islam, neither at an institutional level, nor at a school level, nor regarding associations, and which is more like good news. Yet the government and the media have only that word on their lips, while wanting to combat [the establishment of] separate communities.

Now, if 30% of Jewish children are reportedly in religious schools [according to Jewish publication L’Arche in May 2004], the number concerning Muslims can’t be more than 0.1% given that there are no more than ten Muslim schools in France, with parents preferring to send their children to Catholic schools.

There is not, among the vast majority of Muslims, a desire for being within a community, and if the Ramadan is the most respected ritual it is because it also fulfills a convivial function in places where there is a crisis of conviviality. To say that the Ramadan is the practice of a community is like saying that Christmas for Christians, or the festnoz for Bretons, are acts of a community. There are some who say that.

We don’t even know how to party anymore, as Charlie would have said.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this interview can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse