Stéphane Hessel, son of the writer and translator Franz Hessel and fashion journalist and writer Helen Grund, was born in Berlin on October 20th 1917. He arrived in France at the age of seven, became a naturalised French citizen in 1939, and after the outbreak of World War II joined the Resistance movement. He was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp from where he escaped during transfer to Bergen-Belsen.

After the war, he helped draft the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and became an honorary ‘Ambassador of France,' appointed to special government missions abroad.

Hessel made resistance to injustice his lifelong mission, arguing that “to create is to resist, to resist is to create”. A political activist with a long association with the French Socialist Party, he was well-known in France as an outspoken campaigner on numerous issues, from granting immigrants the right to vote to support for an independent Palestinian state.

He hit worldwide celebrity (see here and here) with the extraordinary success of his book ‘Indignez-vous', first published in 2010, which was a public appeal for a movement of indignation and action against the injustices of modern society. The manifesto was translated into several languages, published as 'Time for Outrage' in English, selling 4.5 million copies in all and was credited with at least partly inspiring recent social protest movements such as Occupy in the US and the Indignados in Spain.

The runaway success of the book, which captured French public imagination like no other political essay in recent history, was also down to the extraordinary popularity of Hessel, an erudite, sharp-witted, gentle and sprightly man who was, right up to his death, a regular public debater.

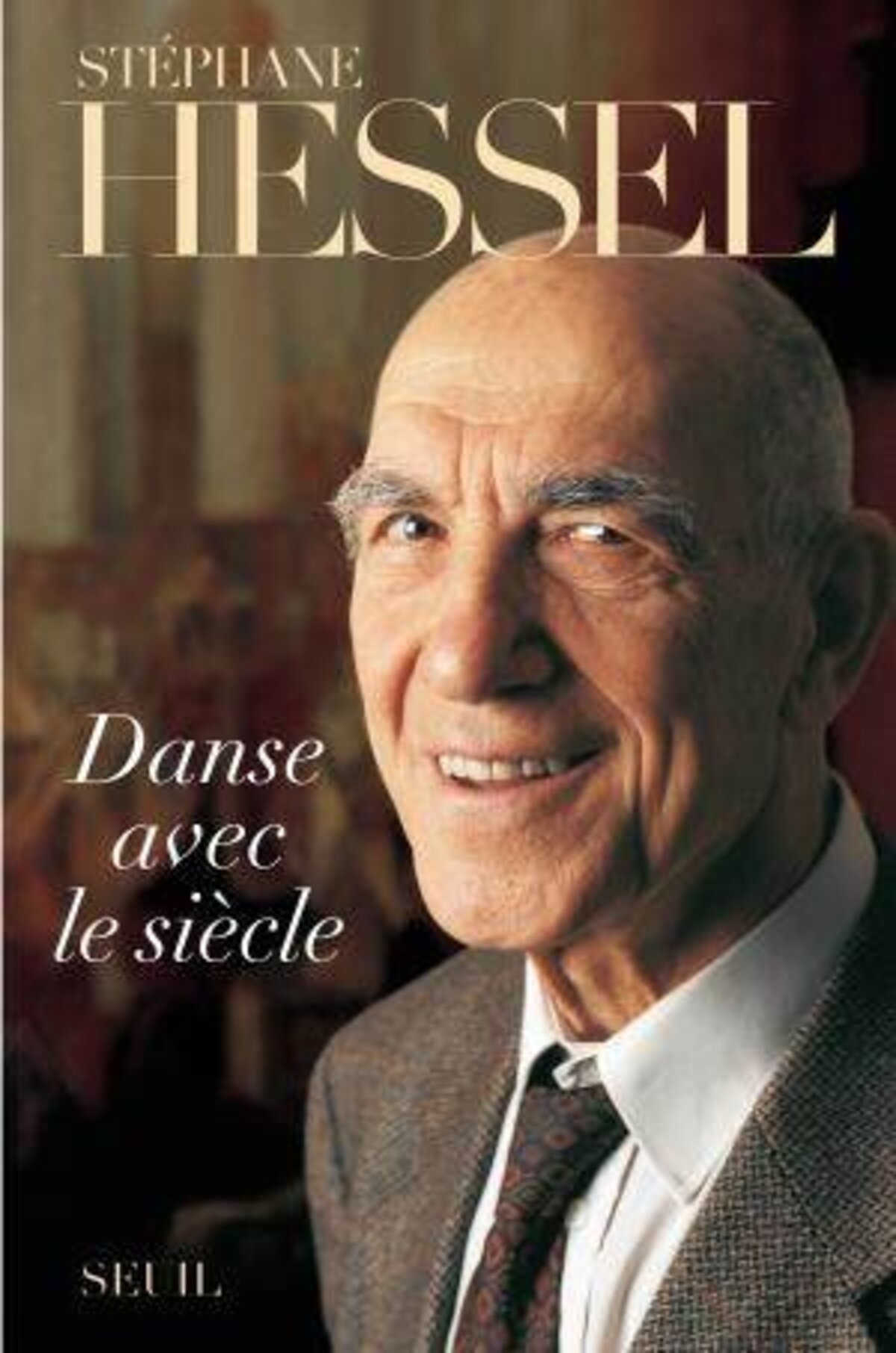

In 1997 he published an autobiography entitled ‘Danse avec le siècle' (Dance with the century), when he was interviewed by Sylvain Bourmeau for the French cultural magazine Les Inrockuptibles and which Mediapart re-publishes here below.

Hessel details the events that profoundly marked his life, about his parents, (whose love triangle with the writer Henri-Pierre Roché was the subject of the novel Jules et Jim, and François Truffaut's film by the same title), and charts his political engagement and cultural influences.

But he began by explaining how his escape from execution in Germany in 1944 left him with the sense of a purpose he must fulfil.

-------------------------

Stéphane Hessel: From my earliest childhood, I've had the feeling of being blessed by the gods. I often quote these verses from Goethe, one of the great heroes of my youth, ‘The gods bestow all the joys on their favourites, but also all the sorrows.' As a small boy I was very influenced by my mother, an ambitious, cultured woman, a big personality. I was the person who was going to prove that they were lucky. That could have made me someone very conceited or very lazy. On the contrary, it galvanised me each time, even when I encountered problems. I had a brush with death on several occasions, just like, and I insist on this, almost everyone of my generation.

I went to war and I seized this existential luck, in a way, to find myself in front of serious challenges, both personal and collective. Of course, the strongest moment was when my life was saved rather miraculously in Buchenwald. When I arrived I didn't know I was condemned to death, I thought on the contrary that the war was as good as finished. And then suddenly we realised that we were condemned men awaiting the execution order from Berlin. After negotiation, three of us were able to swap identities with three people who'd died of typhus. But they still had to die! Once this operation had succeeded, all this suspense and this tension gave me a great sense of responsibilities. You say to yourself, I am the survivor, so my life must have some purpose. It's a bit moralistic, but when you're young, and I was barely 27, you feel as if you are carrying something. Afterwards, I always had the impression that my life was something that had been saved, therefore it had to be invested in something.

Question: What did you invest yourself in?

S.H.: Well, essentially in the opposite of what almost killed me, [which was] Fascism, Nazism, totalitarianism. So, naturally, I headed for human rights. I abandoned philosophy and more general ideas for diplomacy. In 1945, I passed the Quai d'Orsay [French foreign affairs ministry] exam and went to work for the United Nations. The construction of a united and organised world was what we dreamed of when we were in the camps. Luckily, I found myself in the department of social issues, charged with drawing up the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And this investment in human rights has lasted all my life, since in 1993, even at the advanced age of 76, I was given the presidency of the French delegation to the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna. There I was reacquainted with my Universal Declaration, written more than 50 years earlier.

From this point of view, my book [1] would like to bring a message of confidence in History. Because even in the moments where the history of the world, of France or of Europe, appears the most perilous or the most depressing, like with the Serbs in Yugoslavia, between the lines there is always the unifying thread of a history that has meaning and that gives more and more responsibility and liberty to individuals. Only they are not always aware of it, and depression can only be fought with a vision that is slightly retrospective. To come out of it, I believe you must say what my generation was able to tell itself: Listen, it's going badly today, but remember what a horrible situation we were in 50 years ago. And we came out of it. And then you can regain a slightly positive vision of history.

The Second World War gave birth to two monsters, let's call them Auschwitz and Hiroshima. Humans, in their madness, are capable of carrying out a genocide and, in another form of madness, of making weapons of absolute destruction. In the immediate post-War years we lived with the almost obsessive idea that a new atomic bomb was going to fall. Today, without it being seen as foolish optimism, we can say that there will probably not be an atomic war, that people have realised that this was not a possible solution. Another phenomenon: all my generation, and in particular those who were in the Resistance in France, were torn between communism and anti-communism, and many were fascinated by what was generous, what was grandiose about communism. Some, like many of my friends, experienced the end of communism as a rather sad thing. On the contrary, for me, who from the beginning never considered communism as the solution - because of my philosophical training perhaps, or for reasons of democracy, it doesn't matter - the fact that Stalinism was fought and conquered by its dissidents was a major triumph. I could give other examples, such as apartheid.

That said, I would not like my book [1] to be seen as a kind of hymn to the constant success of the human species - there is much to be said to the contrary - but I think that in reflecting on this, inthinking of my experiences, one notices that by dint of inequalities, history is liable to produce greater equalities. In the end it's because of these notions of imbalance and equilibrium that I called my book Danse avec le siècle [Dance with the Century]. That may seem rather pretentious, rather frivolous too, but I don't like to appear pontificating or serious, things that I am not. My character is after all the legacy of a family that was rather on the margins of society, particularly in terms of morality.

--------------------

1: Stéphane Hessel is referring here to his book Danse avec le siècle (Dance with the Century), first published in 1997 by Éditions du Seuil.

Q: You are referring to the couple formed by your parents and their relationship with the novelist Henri-Pierre Roché, who was inspired by this story to write Jules et Jim, which Truffaut made into a film.

S.H.: Today, a love triangle between two men and a woman appears completely normal, but at the time it was still a bit loose, a bit rebellious. But more generally I was also thinking of the milieu in which I grew up: Marcel Duchamp, the Surrealists, they were rebels for a start. There is therefore a rebel in me that is not always easy to combine with a rather official profession like that of a diplomat. I often ask myself the question: how far can you go when you have acquired, also by luck, the title of ambassador for France, this distinction that the Republic bestows on its old diplomats? Can one, should one still attack its government, take rather barbed positions? I've always concluded that one must, because the most important thing is, after all, what one believes, what one feels as a conviction. It can't be helped if it's viewed badly by some - and I'm sure that it's viewed badly by many people. One must enlist one's forces in the service of the causes in which one believes.

Q: When did you acquire your political awareness, and more generally your awareness of the existence of history?

S.H.: Of course, if you are born in 1917, if you are 20 in 1937... As a small boy I lived in a Berlin where the extraordinarily rampant inflation meant that you carried around billions of marks to buy a pound of butter. I therefore felt the dramatic character of history very early on. But to tell the truth as a child I wasn't much interested in politics. It was instead with anti-fascism that I discovered it - my family background predisposed me, obviously, to see fascism as an absolute evil. My family was not particularly committed, politically.

My father was a translator, novelist, a bit of a philosopher, a lover of ancient Greece. He came from a Jewish family - his father was Polish and settled in Berlin - but didn't have any Jewish culture. And even my grandmother, a good old Berlin Jew, was not concerned with our Jewish education. My mother came from a Prussian family of architects and administrators who had come from Silesia. Our family circle was more literary and artistic than political. Particularly through knowing the Surrealists. And the Surrealists were rather unconcerned, politically, even if they were close to the October revolution.

It wasn't, then, until Hitler's arrival in power, and then the years 1935 to 36, that I started to realise that history is important, that it has meaning and that it should be experienced by investing oneself in it. At the time, I was among those who thought that Nazism was a madness that would disappear, that the Germans would not be stupid enough to allow themselves to be led by this idiotic swaggerer who didn't even speak their language very well. So, instead of being violently against the Munich Pact, as I would have been after the fact if I'd known what was going to happen, I remember rejoicing after Munich that there wouldn't be a war, that we'd get rid of fascism in another way. War was a bad thing in any situation: my generation was pretty pacifist on the whole. We didn't want to repeat the horrors of 1914 to 18. That said, as soon as things turned aggressive of course I changed my position and realised the necessity of going all the way. There was no longer a middle ground. The idea that Pétain, for example, would negotiate with Hitlerism and accept a certain primacy of Nazi Germany over Europe was for me inconceivable."

I didn't deserve the slightest credit for not being Pétainist as so many of the French were. For me it was a perfectly inacceptable solution. I learnt a lot about politics during the war. General de Gaulle was the obvious choice, he was right. And yet, on first sight this didn't seem so obvious. He was a general, he was called de Gaulle, he was very tall, he spoke forcefully. All that could appear very dangerous, and some could not see him as a democrat. But, for those of us living in London these reproaches and suspicions seemed completely unjustified.

Q: Going back to your childhood, if politics was largely absent from it, culture and the arts on the other hand held a very important place.

S.H.: Trilingualism for a start. It's fairly commonplace today, but at the time... After growing up in Berlin, I arrived in Paris aged seven with a perfect command of German, my native language, and a total ignorance of French. I learnt French at primary school, then at the Alsatian school. And about simultaneously I learnt English because my mother was very Anglophile. She loved English literature and poetry and was passionate about Edgar Allen Poe. I therefore had to know English, not just to get by but to plunge into the literature. Just after my bac [1] I went to study for a year at the London School of Economics. Since then I've been just about as comfortable in English as in my two other languages.

-------------------------

1: Baccalauréat, the diploma pupils sit exams for at the end of French secondary school education.

Q: Of all the arts that were part of your childhood, poetry always seems to have taken precedence.

S.H.: Above music, in any case. There were two of us, my brother was three years older but he was born with a brain malformation that left him paralysed on one side, and I tended to protect him. It was as if the world was separated into two for us. For him it was justice, fairness, the father and music - that was his domain and I hadn't to impinge on it. For me it was poetry instead. Painting, too. I never tried to write poems but at 79 [1] I still learn a poem a month by heart. Those that I know are all still in my head, so I have no problems reciting them. I know a lot of Apollinaire, including very long texts like La Chanson du mal aimé [The Song of the Unloved]. I only have to start two lines and the rest follows almost effortlessly. In English too, I also know eight Shakespeare sonnets and two long soliloquies, plus Keats, Yeats, Shelley. In German, Hölderlin, Goethe. These are my small pleasures. When I take the Metro I recite three Shakespeare sonnets, it passes the time.

Q: Has culture always been associated with this notion of pleasure, or did you feel an obligation to cultivate yourself, to learn?

S.H.: Pleasure has always been central. But unfortunately my character always compels me to be competitive - I owe it to my relationship with my mother. She was very ambitious for me because my elder brother - who is a marvelous being, with a faultless morality and for whom I have much admiration - nevertheless represented a slight personal failure for her. She adored him but felt that he wasn't the one who would bring her the self-esteem she truly needed.

Q: She was a journalist?

S.H.: By necessity more than anything. In reality she would primarily have liked to have been an exceptional woman in terms of her love life. And a philosopher, too. She was very cultivated, well acquainted with German philosophy and poetry, her great pleasure was to write aphorisms. But finding herself in France after her amorous adventures, having to make a living after her separation with my father, she became a fashion journalist. She also wrote other types of articles on themes that interested her. In particular she wrote a superb article on the Kristallnacht for The New Yorker.

Q: As a child, how did you feel about your parents' chosen lifestyle? Did you see it as a fact of life, or rather as a proclamation, a theory even?

S.H.: It started as a fact of life of course, which then became a theory, or at least a work of literature. It was an adventure that, at the end of the day, was quite banal: a man has a close friend, with whom he has already shared some amorous adventures before the war. He gets married, gets back in touch with his friend and the latter falls in love with his wife. What's interesting is that in my view my father said to himself ‘Here's something that could be interesting from a literary point of view, which we could work on. I'll let this love bloom, I'll take a step back and observe it rather than trying to thwart it. I'll suggest that they both keep a diary, and then maybe I'll write something on the way in which a man who loves his wife' - because he loved my mother deeply - 'but who respects her taste for freedom and personal choice, views that, how he sustains it. And from all that we'll create a book.' And the book was never written, or at least it wasn't written until a lot later, when my mother's and Roché's diaries were published, fifty years later. It's therefore true to say that the theorisation of the situation was effectively an integral part of what they experienced. It was the Surrealists' generation, they were questioning what appeared as the last vestiges of bourgeois morality. They are not the only ones to have done it, but they did it entering into the game, the fun of it.

Q: Of all the Surrealists, painters and writers who crossed your path, you seem to consider Marcel Duchamp as the most important figure.

S.H.: He taught me to play chess. Again this competitiveness: my relationship with Duchamp couldn't be summed up by admiration for this exceptional and very likeable man. What was completely exemplary in Duchamp for us was this attitude of detachment towards art and its traditional forms. Art was academicism, one had to repudiate it in the most radical way possible, to invent a stance. Deep down, this was also rather what I remember from my parents: a radical attitude towards things. It's an approach that I probably didn't inherit. I am a lot less radical than they were.

Q: Much later, when Roché's book Jules et Jim appeared, how did you react?

S.H.: I found the book itself well written, in a rather different style to what one is used to. The story didn't really interest me, I already knew it, and then I wasn't completely in agreement with how he used it for his novel. The book was rather overlooked. The film was obviously an interesting time, especially for my mother. She very much admired Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau. She met them and wrote letters to Truffaut, it was a fruitful correspondence. She also told Jeanne Moreau how much she admired the way in which she embodied this character, who was very different from herself of course but very interesting, very well done. But for me the success of the film was an annoyance. It quickly became known that the real protagonists of this film existed, and that they were still alive. So people kept saying, 'Ah, you were the little girl in Jules et Jim?' But it was a good film, and it did bring happiness to my mother, so bravo.

Q: The German philosopher Walter Benjamin, who translated Proust with your father, and the importance of whose work was only measured after his death, was a second significant figure in your adolescence.

S.H.: In Berlin, before he emigrated, he already knew the people who later founded the Frankfurt school - but he was practically unknown. He was unhappy, marginalised, complicated, we considered that we had to protect him a bit against his own depressions. He was easily depressed, his trip to Russia ended very badly. His emotional life was horribly difficult. He really wasn't a radiant personality, I'd almost say the opposite.

Little by little we saw that in some of his analyses he was a precursor of a whole section of modernist thought. For me, it was a great childhood memory, he often came to the house. And then, I had this strange particularity of seeing him a few days before he died. We met in Marseille at the precise moment that he was leaving for the Pyrénées where he committed suicide at the border.

Q: Were you surprised by this suicide?

S.H.: Not really, I sensed that he was very disheartened. He'd lost confidence, lost confidence in America, which hadn't yet entered the war, and I really felt that he might not survive. When I learnt about his death, a lot later, I was saddened, saddened for philosophy even, because he still had a lot more to say. The manuscript that he was carrying with him has never been found, it's a big loss.

-------------------------

1: At the time of this interview Stéphane Hessel was aged 79.

Q: As a student in London, you were also in contact with important thinkers from another branch of political philosophy, particularly Harold Laski.

S.H.: But I was very young, 15 or 16 years old. I listened to them, I found them marvellous, but I hadn't yet received a real initiation in political economics. That came later, in London too but during the war, with two men who were extraordinarily important in my life, Pierre Mendès France and Georges Boris. It was there that I started to become interested in Keynes, in Bretton-Woods, in the possibility of a fairer world economy. And when Mendès became President of the Council, under the 4th Republic, I was naturally very happy that he accepted me into his cabinet. We stayed in contact until his death. Mendès's thinking is the closest to mine, both as a statesman and an economist. Today, Michel Rocard is slightly his inheritor. Over and above all his political mishaps he remains for me the man of politics who embodies a democratic thought-process akin to that of Mendès.

Most of my friends are in a certain way more Left than me, or at least their interpretation of what is Left differs from mine. I think that any ideological response to economic and political problems that verges on the absolute is in danger of bringing other serious spin-offs, and I've rather been confirmed in this opinion by my experience of history. Today, I feel close to theories of responsibility, like those of the American philosopher John Rawls. In a certain way, what led me later toward this type of thinking was the Club Jean-Moulin. Without doubt this was my strongest personal political experience. We created it in 1958, a few weeks after General de Gaulle's putsch.

Together with a few friends, we said to ourselves, ‘It can't be true - the general is doing the reverse of what he did in 1940. We have to take up the fight that he himself took up at the time. A generals' putsch is as inacceptable as Pétain's seizing of power. Let's resist, let's make up a small group and take up arms.' Naturally it was a bit ill-thought-out, a bit hasty. After three weeks we realised that things were not completely like that. Despite the fact that the republic as we imagined it had been pushed around, we had to reflect together on what a modern republic could be. During this period, I definitely evolved beyond the simple thought of Mendès towards a reflection on new forms of economy and economic justice, on a new kind of unionism.

Q: You've never been tempted by a political career? You've never considered joining a party and standing in an election?

S.H.: I was a member of the PSA [1], the ancestor of the PSU[2]. Because I was both socialist - by education and conviction - and very anti-Mollet, anti-SFIO[3]. For me, these were colonisers. But I have never considered a career as an elected representative - I don't know why, perhaps simply because I was a civil servant, and that seemed to me another way of working. In a certain way it's a shame, too. That is one of the things I reproach my generation for: we were critics of all the successive governments but a lot less constructive. Deep down, I regret it a little. The Club Jean-Moulin was that to a certain extent, we were hoping and praying for a great party, a French labour party that was neither the PC [4] nor the SFIO.

-------------------------

1: Parti socialiste autonome (Autonomous Socialist Party).

2: Parti socialiste unifié (Unified Socialist Party).

3: Section française de l'International ouvrière (French section of the Workers' International).

4: Parti Communiste (Communist Party).

Q: But this tendency of the French Left never succeeded in taking the reins of the socialist party. It was François Mitterrand and not Michel Rocard who was the candidate and elected leader of the PS [Socialist Party].

S.H.: It was a failure, that has to be recognised.

Q: What, then, is your assessment of the Left's years in power?

Enlargement : Illustration 3

S.H.: I will perhaps be less harsh than some of my friends. The mere fact of a change in power was a very good thing for France. From the first months, with people like Nicole Questiaux or Jacques Delors, there were a certain number of victories, especially in the field of human rights. But my main reproach towards the politicians of every country is the lack of courage, the desire to flatter the electorate rather than making progress. The abolition of the death penalty was done probably against the opinion of the majority of French people. That was very good, but beyond that not a lot has happened. It goes without saying that I am quite harsh on Mitterrand himself on that count. In his last years in office, in particular, he no longer inspired in me the kind of respect that I would like to have for a president of the [French] republic.

That said, you cannot count solely on governments to pursue the objectives that we would like to achieve, there is civil society too. Its initiatives must be encouraged. Out of necessity, I have become a member of a phenomenal number of associations, clubs, think tanks.All of them have come to the same conclusion: in France we are very behind in the mobilisation of civil society. We live in a culture of government, a culture of the State. When we are in difficulty we ask the State to sort it out.

Q: You have been a member of the Collège des médiateurs [College of ombudsmen/mediators]. What lessons have your taken from the mobilisation of the sans-papiers [1]?

What has happened is very important. Suddenly we realised that these people that we were trying to defend, for whom we were trying to find small solutions, were men and women capable of asserting their place in society and asserting it without shame. This affair also revealed the hidden vices of industrial societies. If you push society's most burning problems to the side the result is it leaves an opening for the extreme right. As no solution is found for the problems of the [deprived, high-rise housing estate] suburbs, we blame immigrants, we fight them with repression and we let the sources of tension multiply.

The College of ombudsmen has felt it strongly. Each time we've offered a solution, and we've been doing nothing but that, we've felt a reticence from the government but also from a large part of the population who have seemed to be saying, ‘So how are our problems going to be sorted out?' This will be the central problem for Europe at the beginning of the 21st century. Either you create a Europe that puts the accent on the problems of employment, of youth, of architecture, of town planning, and you can build an interesting Europe, or, on the contrary, you put the accent exclusively on the monetary system and productivity, and you run straight into setbacks. The sans-papiers brought this problem to light with greater force, and from this point of view they also played a very useful role.

© 1997, Les Inrockuptibles and Sylvain Bourmeau

-------------------------

1: Sans-papiers - literally 'without papers' - signifies mostly illegal immigrants without any official documents or recognition, unable to integrate into mainstream society. Many have already lived in the country for a significant period of time.

English version: Alison Culliford

(Editing by Graham Tearse)