It was supposed to be a matter of several weeks, or a few months at the most, the French presidency and defence ministry led us to believe. The duration is now to be counted in years. Nothing has gone as planned in the two ongoing French military interventions in Africa launched by President François Hollande – in Mali, which began in Januray 2013 and in the Central African Republic (CAR), which started in December 2013. Almost 4,000 military personnel are now engaged in the operations, with more reinforcements due to join a larger campaign across the whole of the Sahel region of North Africa.

The French army now finds itself enduringly bogged down in particularly dangerous terrain without its European neighbours, nor African states or the United Nations, being in a position to effectively take up the relay.

The two French military operations are quite different in character. The first of them, in Mali, was presented as an “anti-terrorist” campaign aimed at eliminating jihadist groups that have destabalised the Sahel region and which at one point had threatened to overrun the Malian capital Bamako which, had it happened, would have caused the collapse of the state of Mali. The second, in CAR, has been presented, according to circumstances, as a humanitarian or peace-keeping operation. The decision to intervene in CAR was, in the description given by French foreign minister Laurent Fabius, an attempt to prevent “a pre-genocidal escalation” in a chaos-ridden country.

One-and-a-half years after the launch of the offensive in Mali, and seven months after the intervention in CAR, the positive results of the two are not just sparse. In Mali, the current situation appears highly unstable, with French defence minister Jean-Yves Le Drian increasingly losing patience with the obstacles that have led to a stalemate in the country’s political process since last autumn. Furthermore, if Le Drian has announced an end over the coming months to the military campaign in Mali, codenamed ‘Operation Serval’, he has also stated that one thousand of the 1,600 French troops involved in it will remain stationed in France’s former colony.

Above all, he has now announced a new operation across the Sahel, codenamed 'Barkhan'. “We will very soon begin a regional military operation that will involve about 3,000 men,” the minister told French daily Le Monde. “The unique aim now is counter-terrorism,” he added.

Meanwhile, the French presidency on Tuesday confirmed the death of another French soldier engaged on a reconnaissance mission in the north of Mali, the ninth French serviceman to die in the country since the campaign began.

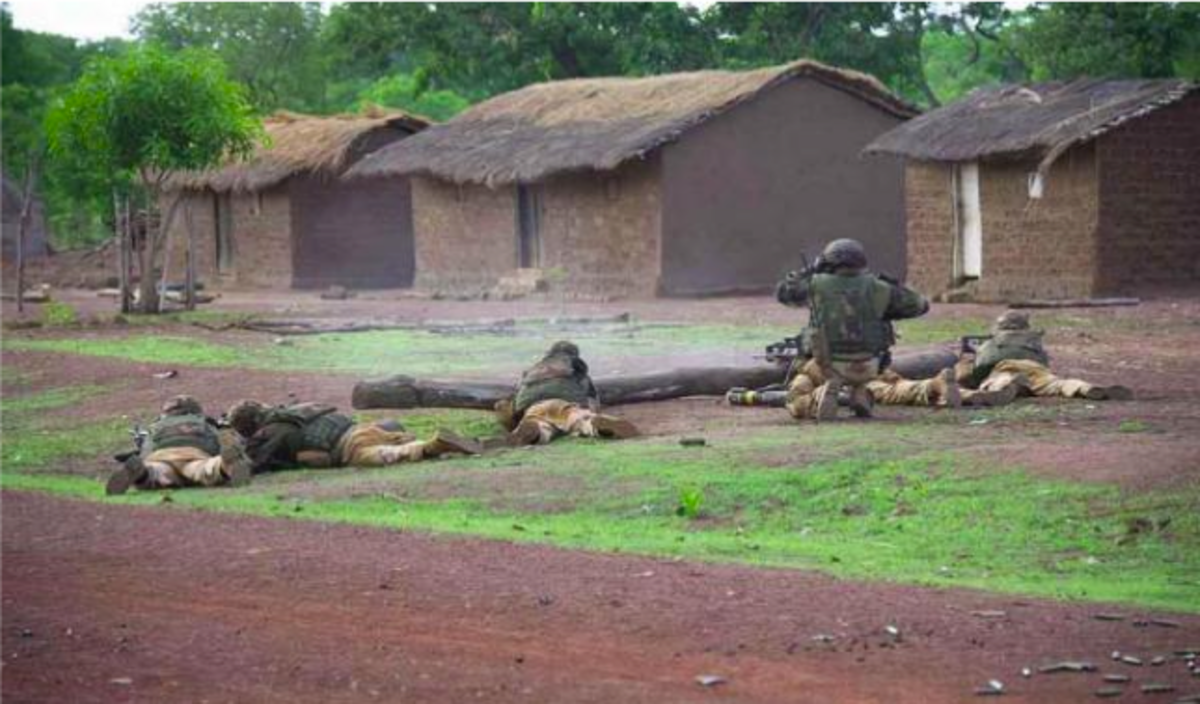

Enlargement : Illustration 1

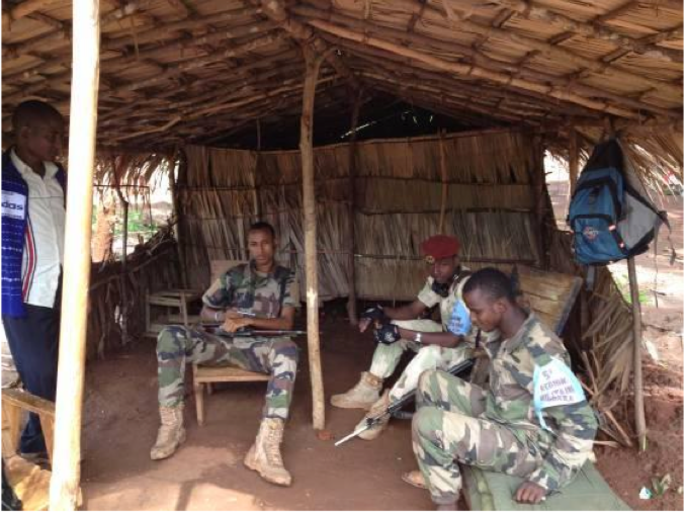

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In CAR, the presence of 2,000 French soldiers has done nothing to halt the terrible violence inflicted upon the civil population by armed gangs made up variously of political factions, looters and bandits.

In both countries, the French army appears to be in the worst-case scenario: it is operating without military allies – with the notable exception of assistance from Chad – still awaiting any real mobilisation of African or other international forces and with no significant support from other European countries. The result of all this is not only to severely limit the army’s scope of action, as in CAR. It also isolates the French military command which thus appears to be behaving much in the manner of the post-colonial period known as ‘La Françafrique’, when France continued over several decades (and until very recently) to control in its own interest the destinies of the newly-independent states that were once part of its former African empire.

Numerous reports by leading NGO’s, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Survie, and also others by UN-sponsored groups of experts have raised the alarm over the catastrophe unfolding in CAR and which the presence of the French military is insufficient to prevent. Since the beginning of July, 11 French troops have been wounded in confrontations with armed gangs in the country. The latter have continued over recent months to reinforce themselves in weapons and financial resources gained partly from looting but also from operating gold and diamond mines and trafficking of diamonds. “A deadly cycle of sectarian violence is escalating in eastern parts of the Central African Republic,” wrote Human Rights Watch in a presentation of its latest report on CAR, released on July 15th. “Scores of civilians have been killed since early June 2014 and tens of thousands displaced from their homes, adding to the hundreds of thousands who have fled their homes since the violence began in March 2013,” the NGO reported.

Since the defeat of the Muslim militias of ‘la Séléka’, the rebel grouping from the north esat of the country that overran the capital Bangui in March 2013, and the setting up of a provisional government in January this year, the crisis has become a multidimensional one, with the violent conflict between Christians and Muslims, the latter falling victim to pogroms along with the almost total expulsion of those who once lived in Bangui, and the manipulation of the militias roaming the land by governments of neighbouring countries. The militias, partly made up of armed bands of looters, include the anti-balaka groups that were initially created by Christian communities in defence against attacks by the Muslim-led militias and which today are made up of bandits and also allies of François Bozizé, the president ousted by the Muslim rebels in March 2013.

All this has created a chaos in which killings and lootings are carried out unchecked. In a report dated March 3rd, the United Nations (UN) described the situation as follows: “Killings are reported daily in Bangui. Violence in the capital has reached gruesome levels of cruelty: corpses are mutilated in public and dismemberments and beheadings take place with total impunity. Targetted attacks by anti-balaka groups prevent Muslims from moving out of the few neighbourhoods where they have regrouped. The vast majority of the Muslim population of Bangui has fled and those Muslims who remain live under international protection […] many towns that used to have multiconfessional populations, such as Yaloke, Bossemptele, Bozoum and Mbaiki, have been emptied of their Muslim communities.”

The scene is set for long-term instability

Four months later, and despite the deployment of 2,000 French troops in the campaign codenamed ‘Sangaris’, the situation has hardly changed from that described in the UN report. If the state of security in Bangui appears to have improved, armed groups have taken rein, forced their positions around the rest of the country. The French military have found themselves in conflict with both pro-Christian and pro-Muslim militias. In a subsequent report published on July 1st, a UN committee of experts drew attention to the continuing violence and the impunity of those responsible. “The total impunity that allows individuals to engage in or provide support for acts that undermine the peace, security and territorial integrity of the Central African Republic remains the main stumbling block on the road of political transition,” it read. “Repeated cycles of violence in the country have been fuelled by this lack of accountability, which has created fertile ground for rebel and criminal activities in the country […] Some members of the international community expressed frustration to the Panel about the absence of strong condemnation from the transitional authorities of the abuses perpetrated by anti-balaka militias.”

Their report identifies two new elements in the chaos. The first is the proliferation of weapons, due to the collapse of the country’s armed forces, many of whose officers variously joined up with pro-Christian and pro-Muslim militias. The experts noted that the dissolution of the Séléka led to the impossibility of any control over the stocks of arms and munitions previously held by the CAR government. The market price in the country for a Kalashnikov automatic rifle is about 80 US dollars, while Chinese made grenades can be found for between 1 and 2 dollars, and an anti-personnel mine for less than that.

The second new element identified by the UN is the appropriation by armed groups – and in particular those of the Séléka – of gold mines (the produce of which is smuggled to neighbouring Cameroon via Bangui), and trafficking in diamonds and wood. “The temporary suspension of the Central African Republic from the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme in May resulted in a ban on official diamond exports,” their report noted. “Buying houses in Bangui have nevertheless continued to officially purchase and stock diamonds from all production areas, while fraudulent trade, routed either through Bangui or through neighbouring States, is on the rise. Many diamond collectors who fled western Central African Republic following anti-balaka sectarian and religious violence at the end of 2013 are presently in Cameroon to continue their business.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Enlargement : Illustration 5

On the political front, there has been little if any progress made over the past months. On January 20th, Catherine Samba-Panza, former mayor of Bangui, was appointed as the country’s new president by the National Transitional Council, acting under strong pressure from France, replacing Séléka-backed Michel Djotodia who came to power in March 2013. But the appointment has satisfied none of the parties involved, and neighbouring countries - and notably Chad which is the most involved in CAR’s crisis – regard her with suspicion. The plan to hold elections, which France at one point announced were due this autumn, is nothing more than a wish given that nothing remains of the administration or anything else of the state structure.

“Questions about the legitimacy of the current transition could derail the current Government, especially insofar as they touch on the sensitive issue of representation,” wrote the UN experts. “The country has a long history of failed transitions and weak peace agreements. Since Mr. Bozizé seized power in 2003, rebellions have mushroomed in the Central African Republic and then been followed by a series of agreements that have not been implemented seriously. Mr. Bozizé’s fall can be blamed on, among other things, a lack of political will to implement political agreements and to seriously engage in disarmament, demobilization and reintegration efforts.”

All of which highlights the fragility of French defence minister Jean-Yves Le Drian’s comment that “the solution in Central Africa will only be political”. At the end of this month the leaders of CAR’s neighbouring states are to hold a conference in the Republic of Congo capital Brazzaville. A previous such conference in June, when Catherine Samba-Panza was allowed to attend only after strong diplomatic pressure from the international community (although she was asked to leave the discussions after just a few minutes of presence), produced no result. Everything then is set for a lengthy period of instability in CAR, when it will remain under international guardianship while each of the neighbouring states, beginning with Chad, continues to place its own interests to the fore.

No political progress and no exit on the horizon

France’s hoped-for handover of military intervention in CAR has still not taken place. Alongside the French contingent, an African Union force of some 5,800 soldiers is officially present in CAR. Those initially supplied by Chad were ordered to pull out of the joint force after a number of them were implicated in attacks upon civilians, and those remaining in the country are camped down in a few strongholds. As for the UN and a mooted deployment of a peace-keeping force in CAR as of September, the organisation’s official reports illustrate the growing hesitations over such an engagement, with the fear of repeating the situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where 17,000 UN troops have remained stationed since 2002.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Everything remains to be done in CAR, where more than half of its population of 2.5 million require food aid and where the framework of the state has vanished. The country has no army, its public sector employees have not been paid for the past four months, its education system has ground to a halt, and its justice and police systems have disintegrated. This disappearance of the state is most worrying regarding the continuation of the violence in the country, where killers and gang leaders walk freely around Bangui and other major towns.

In a very detailed report published on July 10th, Amnesty International gave a list of names of people responsible for the horrors taking place. “The presence of international peacekeepers has failed to put an end to the violence,” the rights organisation noted in its presentation of the report. “Peacekeeping forces, including Chadian soldiers, have even been involved in serious human rights violations. The most serious incident occurred on 29 March when Chadian soldiers opened fire on civilians in a Bangui market and, according to the United Nations, killed at least 30 people and injured 300. The fight against impunity must extend to the investigation of suspected human rights abuses by the soldiers and officers of the Chadian national army in this and other incidents in CAR.”

Amnesty International proposed that "a hybrid court composed of national and international experts could be created to try crimes under international law and help strengthen the national justice system”, adding: “This court would not prevent cases being prosecuted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) which has opened a preliminary examination of the situation.”

But above this, the NGO highlighted the problem of the disappearance of any kind of structure providing security. The only prison in the country still - officially - functioning is that of Bangui, which since January has been the scene of mass break-outs of prisoners including gang leaders. “The absence of investigations has created a climate of impunity and resulted in a situation where judges, prosecutors, members of the Police and Gendarmes are unwilling to take the risk of even going to their offices to resume work,” reported Amnesty International. “There is a noticeable climate of terror among magistrates, lawyers and other judicial personnel in the country. One Bangui-based magistrate told Amnesty International that he could not risk his life because there is no protection for him when suspected perpetrators remain at large, most of them too powerful and fearless. The Bangui prosecutor told journalists at the end of May 2014 that all criminal proceedings were suspended, because of lack of serenity for the investigating magistrates and fear for their lives and those of their family members.”

So has French intervention saved CAR from the worst? All the reports indicate the contrary and a debate over its advisability and pertinence is now beginning in France. “The French intervention has no doubt slowed a very dangerous escalation, but it could also have encouraged unreasonable hopes and liberated destructive forces, from which comes the complexity of the task,” noted conservative opposition UMP party Senator Christian Cambon, who was part of a Senate fact-finding mission on the situation in CAR in April. One of his politically-opposed colleagues in the mission, Communist Senator Michèle Demessine, observed: “The people from the transitional [authorities] are excellent for dialoging with Western capitals and fund providers, but that has no effectiveness on the ground.”

Enlargement : Illustration 7

For its part, the defence committee of the French parliament’s lower house, the National Assembly, earlier this month questioned two Members of Parliament (MPs) who led a fact-finding mission on current French military intervention in Africa. Both of them, conservative UMP party MP Yves Fromion and Socialist Party MP Gwendal Rouillard, expressed concern over likely ‘mission creep’ in CAR. “There, again, as in Mali, the scenario for the exit of operations is less than clear,” said Fromion. “The Sangaris force did the best with what it had: 2,000 men and little backup. The Central African army is no longer other than virtual, and neither the police nor the gendarmerie has the slightest [presence] outside the capital. There is no [function of the] state outside Bangui.”

The predicament is that the situation of the French military intervention in CAR is a mirror image of that in Mali, one-and-a half years' on. Despite the obvious differences between the two countries and the conflicts experienced, the two MPs are struck by the fog that has beset attempted progress in the political processes, and also the scenarios to allow for a French exit.

“The situation in Mali is far from being stabilised, and the disappointment, not to call it otherwise, of the Malian forces during the adventurous mission they led in the north [of the country] in the month of May, despite all the warnings, suffices to prove it,” said Rouillard.

The Malian army met with defeat in an operation in May to regain control of the northern town of Kigal from Tuareg forces belonging to the separatist National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). The Azawad is a territory in northern Mali. The rout was a cruel reminder of two things: firstly, that the Malian army remains poorly operational in spite of training and organizational advice by instructors from France and some other European countries. Secondly that the refusal by the Malian authorities to negotiate a lasting political agreement with the populations and Tuareg movements in the north of the country is a block on any stabilisation of the country.

Forced into alliances with despicable regimes

“Inter-Malian dialogue, meaning the renconciliation process between Malians, is stalled,” said Rouillard. “The experience of our OPEX – exterior operations – in Africa shows that we can be there for a long time. [Operation] ‘Epervier’, in Chad, has lasted since 1986, and ‘Licorne’, in Ivory Coast, since 2002 […] If no political initiative is taken concerning, in the north, those who are keen to discuss, we can fear the effects of porosity between the armed groups which signed the agreement of June 18th 2013 and armed terrorist groups of every obedience. There must be no delay.”

But there is still no move for the dialogue so desperately needed. Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, whose candidature was openly supported by France during presidential elections last year, has no desire to discuss possible autonomy for the northern regions.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Beyond the reservations now being expressed by some MPs – a rare event concerning French military operations – several NGOs have also underlined the incoherencies and impasses of French policy. The most virulent of these is the association Survie, accustomed to denouncing the ills of the ‘Françafrique’ networks, and which warns of “the destabilising risks of foreign interventions”. It recalled that in order to manage the two crises in Mali and CAR, France has had to once again ally itself with some of the most unpleasant regimes in Africa: that of Paul Biya, leader of Cameroon since 1982, that of Idriss Déby, who has ruled Chad since 1990, and also Denis Sassou Nguesso president of Congo-Brazzaville since 1979 and Blaise Compaoré, leader of Burkina Faso since 1987.

It is in an attempt to regain the initiative that French President François Hollande and his defence minister Jean-Yves Le Drian travel this week to Africa. Le Drian arrived in the Malian capital Bamako on Wednesday to sign a military cooperation deal, held up for six months over disagreements with President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. Hollande, meanwhile, will travel to Ivory Coast, Niger and Chad between Thursday and Saturday to detail to his counterparts the forthcoming French military campaign in the Sahel region. Importantly, Hollande wants to ensure the full cooperation of Chadian leader Idriss Déby, the strongman of the region, whose country’s capital is to be the site of the command base for the French mission.

For France, without particular coordination with its European partners nor the US – and who are regularly accused by French political leaders of leaving France to carry out the dirty work abroad – has decided to reinforce its presence in the Sahel by remodelling its military presence in different African countries. There are to be 3,000 French troops durably stationed in the region, while personnel at other bases, notably in the Gabonese capital Libreville, in West Africa, and in Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa, will be scaled down.

All of this explains how the French army has once again become heavily and enduringly engaged in campaigns in Africa, stemming from what were presented to public opinion as urgent operations, anti-terrorist (Mali) or humanitarian (CAR) in nature, and limited in time.

Hollande and his ministers have repeatedly insisted that France has no particular interests in Mali and CAR. Yet it is now France that is struggling to hold up their regimes from collapse, offering itself once again to accusations of neo-colonialism.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse