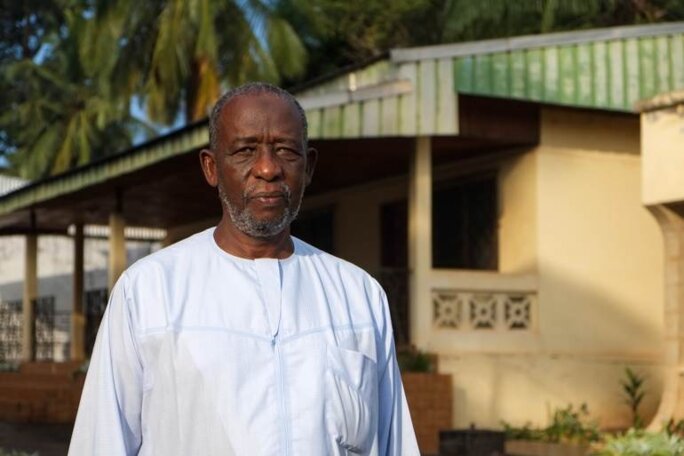

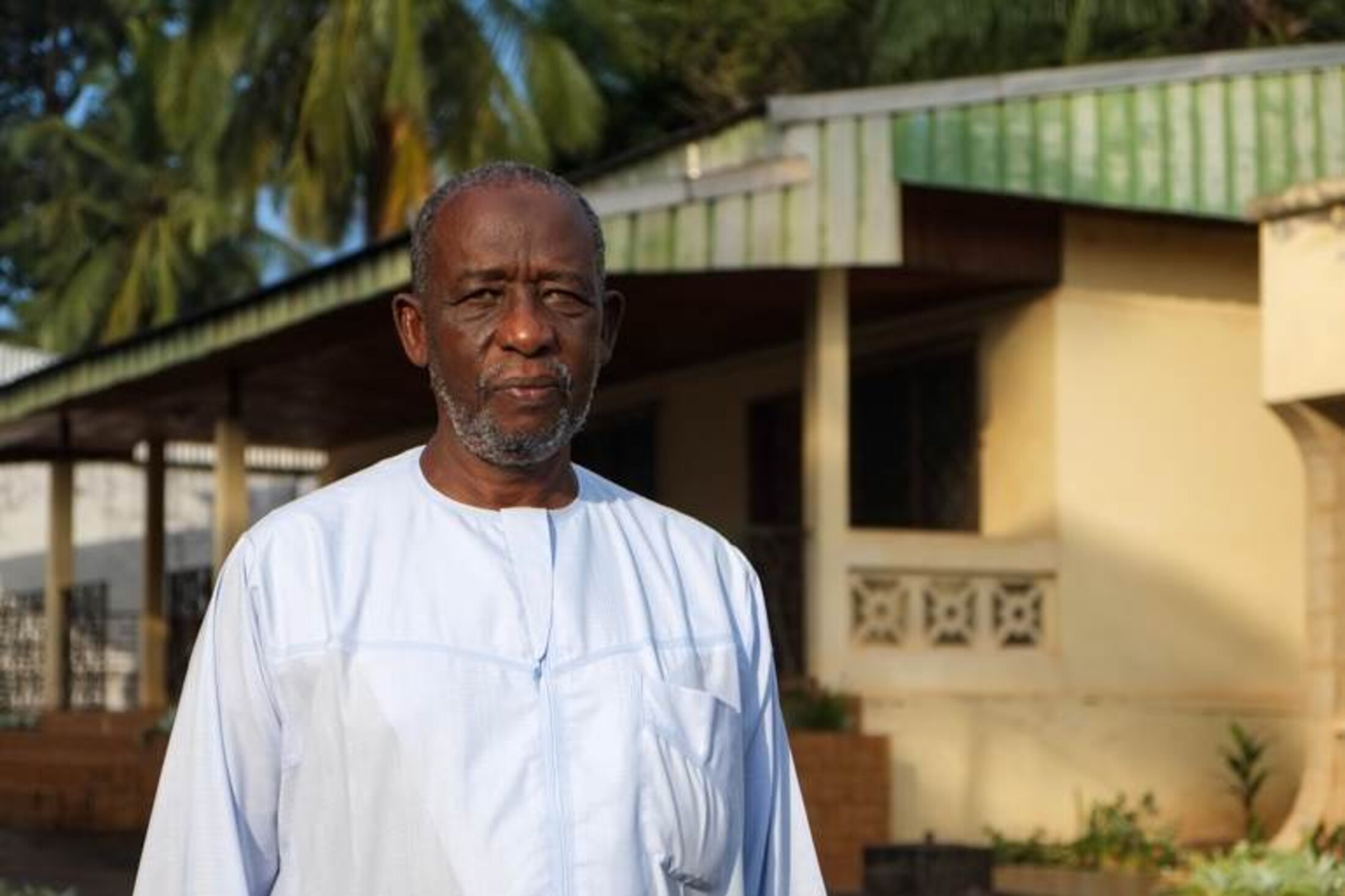

Félix, 64, has the sickly look of someone who knows his days are numbered by HIV/AIDS. He is sitting in the porch of his modest dwelling in Carnot, the third largest town in the Central African Republic (CAR), with its two rooms, a single window and the luxury of breeze-block walls. Yet when he talks about the 50 years he spent as a diamond miner, his eyes light up. “Before, from the 1970s to the 1990s, there was enthusiasm. There was money, we could give some to friends. Now it is catastrophic – we have not known anything like it since independence,” he says.

He began as a child, working during the school holidays digging the earth in this western part of the Central African Republic known for its diamond reserves. “There were roads, schools, street lighting and about a dozen diamond-buying offices. There was life, and Carnot was an important town – you could find everything here you would get in the capital,” he recalls.

Nowadays this town of 40,000 inhabitants – named after the French president Marie François Carnot who was assassinated in 1894 - bears only a few clapped-out remnants of that era. The street lamps no longer work, the tarmac on the main thoroughfare has been completely worn away, and the diamond insignia painted on the walls of some houses are more relics of the past than proud statements.

From one end of the country to the other, everyone from government ministers to street hawkers repeats endlessly that CAR is a rich country with plentiful resources – gold, uranium, diamonds, oil, water, and a fertile soil. Yet this remains a desperately poor country, right down at the bottom of international league tables for wealth or welfare. Félix, for all his recollections about enthusiasm and money, concedes he “never saw a miner get rich”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Corruption, incompetence, indifference, foreign pillaging, political instability and a lack of infrastructure have all been blamed over the years. But since March this year, when President François Bozizé was overthrown by rebel forces, lawlessness has also a major cause of the country’s economic woes.

These factors all explain why CAR is now in a downward spiral. For at least the last three decades it has shown itself incapable either of developing its resources or of developing at the same rate as some of its neighbours. The diamond industry is a case in point, both because it is highly symbolic for the country – the self-styled 'emperor' Jean-Bedel Bokassa gave diamonds as gifts to state visitors, including French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing – and also because the diamond industry has real potential. Despite its limits, it provides an economic lifeline for tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of CAR citizens.

Some 20 km from Carnot, along paths that cross coffee and manioc plantations, you come across an opencast mine, a stepped scar in the earth about 10 metres deep. It is deserted. “An artisan [editor's note, local terms for small-scale independent miner] died in a landslide 10 days ago,” says Aristide, Félix's nephew. “We are waiting for the mourning period to end before going back to work.”

About 100 metres further on, another mine is in operation. Bare-chested men work under the burning sun. Those at the bottom of the mine dig the ground while the others carry the earth up to the top, a spadeful at a time, and empty it into large baskets, which are then carried on their backs to the river below. They then sieve this earth several times under the scrutiny of the mine owner or the collector who financed the mine. When only stones remain, the collector examines them, and if he finds a diamond, he pulls it out.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In these troubled times the miners fear any publicity about diamond finds. “The Sélékas [the militias that control the country] are trying to rip us off. If they find out there is a rough diamond, they will do anything to get hold of it,” Aristide says. “At such a time we stay in the bush, and we don't go back to the village, to avoid being robbed, but that is not always enough. Sometimes the Sélékas come right to the mines themselves.”

'Mining diamonds is like playing poker'

Over the course of many decades a settled economic chain has developed in CAR's diamond industry. Small-scale independent miners dig the ground, collectors recover the diamonds and sell them on to diamond-buying offices that deal with customs paperwork and taxes due to the capital Bangui before exporting them, usually to Antwerp in Belgium.

That, at least, is the official chain. For diamonds can and do leave this economic chain illegally at any point. Miners, collectors or buyers can keep diamonds for themselves whenever they choose. “Under [deposed president] Bozizé 80% of the diamonds left the country illegally. Now it must be close to 100%,” says a European diplomat based in Bangui.

Since CAR was suspended last May from the Kimberly process -the certification scheme set up in 2003 to stop what's known as 'blood' or 'conflict diamonds' being sold in mainstream markets - there is in fact no legal way to export diamonds from the country any more. But it is not hard to get them out.

When asked whether miners are tempted to sell stones outside the legal circuit, one Carnot miner notes matter-of-factly: “You know, we're close to the Cameroon border”. And when a diamond buyer in Carnot is asked what happens once the diamonds reach Bangui, the reply comes back: “It's better not to know.” Until Air France changed its schedules from CAR in October, its Bangui-Paris flight was nicknamed “le vol des diamants”, a play on words in French, with “vol” meaning both flight and theft.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Clearly the illegal diamond chain brings no revenue to the CAR government. But it could at least bring some much-neded income to the various players involved in the chain, were it not practically at a standstill. This business, like any other, needs stability and investment, and right now it lacks both.

All the players in the economic chain are linked. Miners borrow from the collectors, the collectors are financed by the buying offices, which often act as their banker, and the buyers themselves need to sell rough diamonds on the market to have capital of their own. “With diamonds, it's like poker,” says Ali-Babo, one of CAR's biggest collectors. “You have to dig a lot for nothing before you win a packet one day. If you don't have enough money to invest, you don't earn anything.”

Now there is no more money around to invest, he says. “I don't even have enough to fill my Caterpillar up with 600 litres of diesel.” Miners are continuing to dig on a very small scale, but that is not a viable economic activity for supporting thousands of families.

The problem is not the fact that the mining is done by small-scale miners, says an economic advisor at a Western embassy in Bangui. “Diamonds in the Central African Republic are mainly alluvial, which means they are on the surface, so there is no need for industrial methods to extract them. What is lacking is infrastructure, capital and political stability,” he notes.

But the industry's problems stretch back well before the current chaos. Since independence in 1960 all the country’s leaders have sought to control the diamond industry by managing the mining sector directly from the presidential palace rather than from the ministry for mines, as is usual in neighbouring countries. To take just recent examples, Ange-Félix Patassé, president from 1993 to 2003, owned a mining company and gave out concessions to his political allies. Bozizé put people close to him in critical jobs and granted or cancelled the buying offices' patents as he saw fit.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In 2009, the medical aid agency Médecins sans Frontières (MSF, 'Doctors without Borders') arrived in Carnot to find far more cases of severe malnutrition than the national average. Most people here had worked in the mines, but three factors suddenly combined to take away their source of income: a worldwide fall in diamond prices; the sudden closure of eight of the country's eleven buying offices; and – not least – an order from Bozizé to seize collectors' assets.

As they had stopped farming to work in the mines, locals could not immediately return to the land and had no more money to feed their families. So an arbitrary political decision brought about a humanitarian crisis in a region with abundant natural resources. MSF still runs some departments at the Carnot hospital “because the health situation in the country remains catastrophic”, says an MSF official here.

'We miners stay poor our whole lives'

In CAR the industry also wrestles with another structural handicap. Here the export of rough diamonds is taxed at 12%, while in neighbouring countries the tax rate is only 1% to 2%. “Obviously that encourages illegal exports,” admits the head of a buying office.

The country's leaders have often talked about the need to reduce this tax rate so as to reduce diamond trafficking and bring money into the government's coffers, but none of them have actually done so. “The problem with the Central African Republic is the people themselves. They haven't faced up to their responsibilities,” says Jean-Mermoz Namyouisse, who heads a small France-CAR non-governmental organisation. “We keep on saying that we are a rich country, but what does that mean without the human resources? We want to drill for oil, but how many petrochemical engineers are there in CAR? We want to do the same things as other people, but we haven't got the expertise. We don’t even have a solid army to ensure security at oil wells or mines.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Even foreign companies have deserted CAR. They benefited in the past from the lack of local expertise, the lax regulations and corruption, but now they are simply no longer interested in operating in the country. “What company is going to spend several million euros to bring equipment and machines to CAR via impassable roads, at the risk of things being stolen after a few months or a few weeks?” asks the Western economic advisor.

For example, Areva, the French nuclear company, had envisaged re-opening its uranium mine at Bakouma, in the east of the country, which had been closed after uranium prices collapsed following the nuclear disaster at Japan's Fukushima Daiichi power plant in 2011. “Just as the company was running an exploratory mission for re-starting the site and hiring staff, armed rebels attacked the installations and stole everything they could. So Areva went to see President Bozizé, who was running the country at the time, and told him, 'you are not even able to guarantee our security, we're pulling out',” says a well-placed French expatriate.

Whether it is uranium or diamonds the problems are the same. “In sync with the French, successive rulers have turned the responsibility of governance into a business opportunity,” the conflict resolution organisation Crisis Group wrote in its report 'Dangerous Little Stones: Diamonds in the Central African Republic' in 2010. It continued: “Lacking the capital to launch its own diamond mining operations or exporting offices, the ruling elite has fed off the largely foreign companies by demanding a share of production and heavily taxing exports. Those in power have used the small but precious state revenue to enrich themselves and their families and buy political loyalty through a patron-client network. The presidency’s sustained involvement in the diamond business led a former politician to say: 'Central African heads of state are first and foremost diamond merchants'.” The report then noted: “Proceeds from diamonds have, therefore, failed to filter down to the large majority of citizens at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Veteran diamond miner Félix knows all this from personal experience. At the age of 64 he thinks he has no right to complain as he owns his own home. However, he still has to live from hand to mouth to feed himself and pay for the education of his children and grandchildren. “We miners stay poor our whole lives because we don't know the price of rough diamonds and we always owe money to the collectors. But as long as you can dig, you can survive.”

The leading Carnot diamond collector Ali-Babo, who started working in the business in 1963, also offers up a bleak view of the situation. “The country’s got worse,” he says. “A few years ago there were still a hundred collectors in the whole country. Today there are just forty of us. In the past, the diamond business drove the country, now we're just waiting for things to get better.”

--------------------------------------------------

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter