The most significant event to emerge in the French government reshuffle announced Tuesday is the replacement of outgoing economy and industry minister Arnaud Montebourg by Emmanuel Macron, a former banker who served for two years until June as deputy chief-of-staff to President François Hollande.

Macron, 36, is regarded as one of the pillars of Hollande’s presidential cabinet, overseeing all major economic and industrial issues, including some of the battles involving France’s biggest corporations, one of the architects of the so-called 'Responsibility Pact', and who was closely involved in important European Union negotiations. By nature of his responsibilities, he regularly worked in cooperation with his predecessor Montebourg, whose outspoken attacks this weekend against his government’s economic policies led to its collapse on Monday.

The two men are known to have had respect for each other, working in harmony over the protracted takeover battle for Alstom’s energy arm, and in disagreement over Montebourg’s confrontation with ArcelorMittal over the shutdown of part of its steel plant in Florange, eastern France. The two men were, according to Macron, united in a vision of “action for industry”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

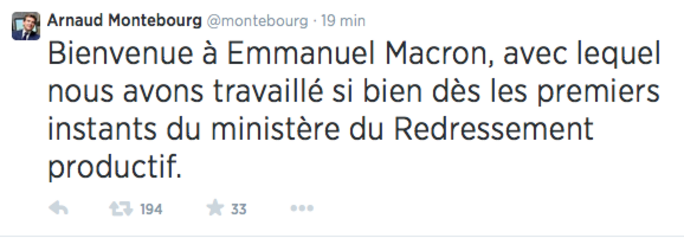

In a Twitter message on Tuesday (see below), Montebourg, self-styled socialist leftist rebel, greeted his successor with the message: “Welcome Emmanuel Macron, with whom we have worked so well as of the first moments of the Ministry of Industrial Revival” – a reference to Montebourg’s first appointment as industry minister (officially titled Minister for Industrial Revival) in Hollande’s initial government led by prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault (from May 2012 until April 2014). In the government that succeeded that of Ayrault, when Manuel Valls was appointed as new prime minister on April 1st this year, Montebourg was promoted to the post of both minister of the economy and industry.

For the left-wing current of the Socialist Party, Macron symbolizes both Hollande’s drift towards pro-business policies and the powerful hold that technocrats have over government. That same current of opinion among the Left of mainstream socialist opinion talked of the victory of what they called the “Macron line” with the announcement by Hollande, in the traditional presidential New Year’s press conference held in January, of the forthcoming Responsibility Pact.

Ayrault – a self proclaimed Social Democrat – did not hide his unease at the situation. “It’s François Hollande, on his own with Macron and a few business leaders, who are deciding matters,” a former Ayrault aide, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Mediapart at the time. “The prime minister is only informed a few hours before [the announcement].

Another source close to Ayrault added: “The prime minister’s office was very business- friendly, but very soon we were uneasy, and it even became a sufferance.” A third source told Mediapart that “the political balance [between Ayrault and Hollande] was lost with the Responsibility Pact”. Ayrault and his team had already run into confrontation with Macron over tax reforms, and notably the issue of merging income tax with the separate health care-funding generalised social contribution levy, the CSG.

Before his appointment as junior budget minister in Manuel Valls’ first government, formed in April, Christian Eckert – who on Tuesday was re-appointed to the post – did little to hide his irritation with Hollande’s economic advisors, beginning with Macron. “One remembers a certain behaviour, notably that of [former presidential chief-of-staff - and subsequently interior minister - under president Nicolas Sarkozy] at one time,” commented Eckert in January. “There are holders of public office. It is not healthy that such precise things, like the tax breaks for households, are announced by a presidential advisor, whatever his competence.”

Macron eventually quit his post as deputy chief-of-staff to the president in June, following the appointment of Jean-Pierre Jouyet, a personal friend of Hollande’s and a specialist in business and economic affairs, to the post of chief-of-staff. Macron gave little information about his future plans, save for the possibility that he might seek a teaching post within a university abroad.

His appointment as Minister of the Economy and Industry – and which also carries the role of management of digital affairs – is indicative of a slide, which is perhaps a definitive one, towards a technocratic leadership of economic affairs at the French Ministry of the Economy. It appears as if political leadership, caught between a rock – the high bureaucracy of the French financial administration – and a hard place –namely, the European Commission – has given up all claim to policy-making on the matter. The trend had already begun under Hollande’s first economy minister Pierre Moscovici, who served under the president’s first prime minister, Jean-Marc Ayrault, and who was replaced by Montebourg in the April 1st Valls government.

Moscovici decided to maintain Ramon Fernandez, a close ally of former conservative president Nicolas Sarkozy, in his post as head of the French treasury department, a position he had held since 2009. Fernandez, who met with approval from the German government, played a major role in European and international negotiations on economic matters and was responsible for a number of compromise deals. Demands by Ayrault’s office that Fernandez be replaced was opposed by stubborn support for him from from Moscovici and the economy ministry’s senior civil servants, before Fernandez finally gave way – to become director in charge of finances at phone operator Orange (headed by his friend Stéphane Richard).

The appointment of Emmanuel Macron has done away with any pretence. He is a recognised member of the economy ministry’s senior administration, an inspector of fiancé who understands all the ministry’s inner workings, methods and manners of approach. He also shares much of its thinking. Unlike Montebourg, he has no feelings of impassioned irritation towards its senior civil servants – notably, for Montebourg, those of the treasury department – and which earnedthe outgoing firebrand minister the nickname, by the mandarins, of ‘the mad one’. Macron’s appointment as economy minister is nothing short of a total victory for the ministry’s administration, who now see one of their own made leader of the French economy without any process of political debate. It will undoubtedly reinforce their widely-shared opinion that while the camel train of ministers come and go, they are always there, managing economic policies.

A long and winding professional road

“Emmanuel Macron is a socialist,” said Prime Minister Valls on Tuesday, in an interview with French TV channel France 2. “In this country cannot one be an entrepreneur, a banker, a skilled professional, a shopkeeper? It’s for years now that we’ve been made lifeless by ideological debates […] About Monsieur Macron, I hear the criticism, the labels that in my opinion are outdated, outmoded. The criticism has come from the Left itself. There are always political alternatives, but I have the belief that that which we uphold is the right one, that which we must continue to revive the country. There are wonderful symbols [in the government reshuffle, and] Monsieur Macron is one of them."

Macron's first professional path was that of philosophy, a discipline in which he obtained a Master of Advanced Studies. In 1999 became became an assistant to the late French philosopher Paul Ricœur. However, he subsequently decided to turn to political sciences studies. “Paul Ricœur published his major books after the age of 60,” Macron said in explanation of his change of direction. “I didn’t have that patience, it was too slow for me.”

After studying at the Paris Political Studies Institute, more often known as simply ‘Sciences Po’, he entered the elite École nationale d'administration, ENA, the top French school for grooming technocrats and future politicians (including François Hollande). After leaving ENA he joined the French General Inspectorate of Finances (IGF), which is the supervisory and auditing department based at the economy and finance ministry.

“Sarkozy helped me a lot and the socialists in the [northern French region of] Pas-de-Calais too,” he once said, explaining the next stage of his professional path with a hint of philosophical relativity. For shortly after leaving ENA he became tempted by a political career, beginning in local politics in Liévin, in the socialist bastion of north-east France. But Macron, a young finance inspector, was regarded with suspicion by the local socialist chieftains as an ambitious figure ready to shake up their patch. “I was a young white male, which could only be a handicap,” recalled Macron, still bitter about the experience. “They never considered that I could bring them something.”

He subsequently returned to fulltime employment at the finance inspectorate. After the election of conservative UMP party leader Nicolas Sarkozy to the French presidency in 2007, there were many among the younger finance inspectors who tried to gain a post in ministerial cabinets, which is traditionally the pathway to a grand future career. “All those in my graduation year left,” he recalled. But Macron’s left-wing views saw him refuse an offer of employment with Sarkozy’s budget minister Eric Woerthe.

He joined the French foreign ministry, less taxing for his beliefs, but was soon recruited by Jacques Attali, a former advisor to President François Mitterrand and who had been tasked by Sarkozy to lead a commission on strategies for economic growth. Few of the 40 or so members of the commission possessed the time or talent needed to organize the meetings and write-up their collective findings. Macron was made the commission’s rapporteur two months after joining it. But like so many such commissions, the projects it lay, presented with great pomp in the media, died at the first sign of popular opposition, notably the plan to open up the closed shop of the French taxi business.

His time on the commission gave Macron a wide professional circle of contacts, and which helped with his next step, away from the sarkozy administration and into the world of private business. Attali’s friend Serge Weinberg, an ENA-trained former civil servant who became a successful businessman, introduced Macron to the Banque Rothschild, which he joined in 2008. “I was lucky,” recalled Macron, “I had a background of very little intelligibility. No-one except at Rothschild’s could have understood it.”

Macron’s new-found career as a business banker taught him about corporate affairs, financial strategies and the operations of multi-nationals., what he later described as “the great rationalities and their aberrations”. He found both pleasure and success in the role, becoming the Rothschild bank’s youngest partner in 2011. However, he never lost sight of his political interest.

At the same time, he had begun working as an advisor to the team of close allies of Hollande then preparing an economic programme for the future socialist presidential candidate. Immediately after Hollande’s election in May 2012, he was appointed to the presidential staff, although there was hesitation over the precise post he would hold: economic advisor or deputy chief-of-staff. For Macron’s talents were required both in the management of economic affairs and also as a go-between with the business world which Hollande had few links with. His post would finally be that of deputy chief-of-staff, in which he managed both missions.

It was not the first time the Rothschild bank in France lost a senior member of its management to the French presidency. Georges Pompidou was its managing director until his appointment as prime minister under President Charles de Gaulle. In 2007, following Nicolas Sarkozy’s election, the bank’s associate manager François Pérol, another ENA graduate, was recruited as the president’s new deputy chief-of-staff.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse