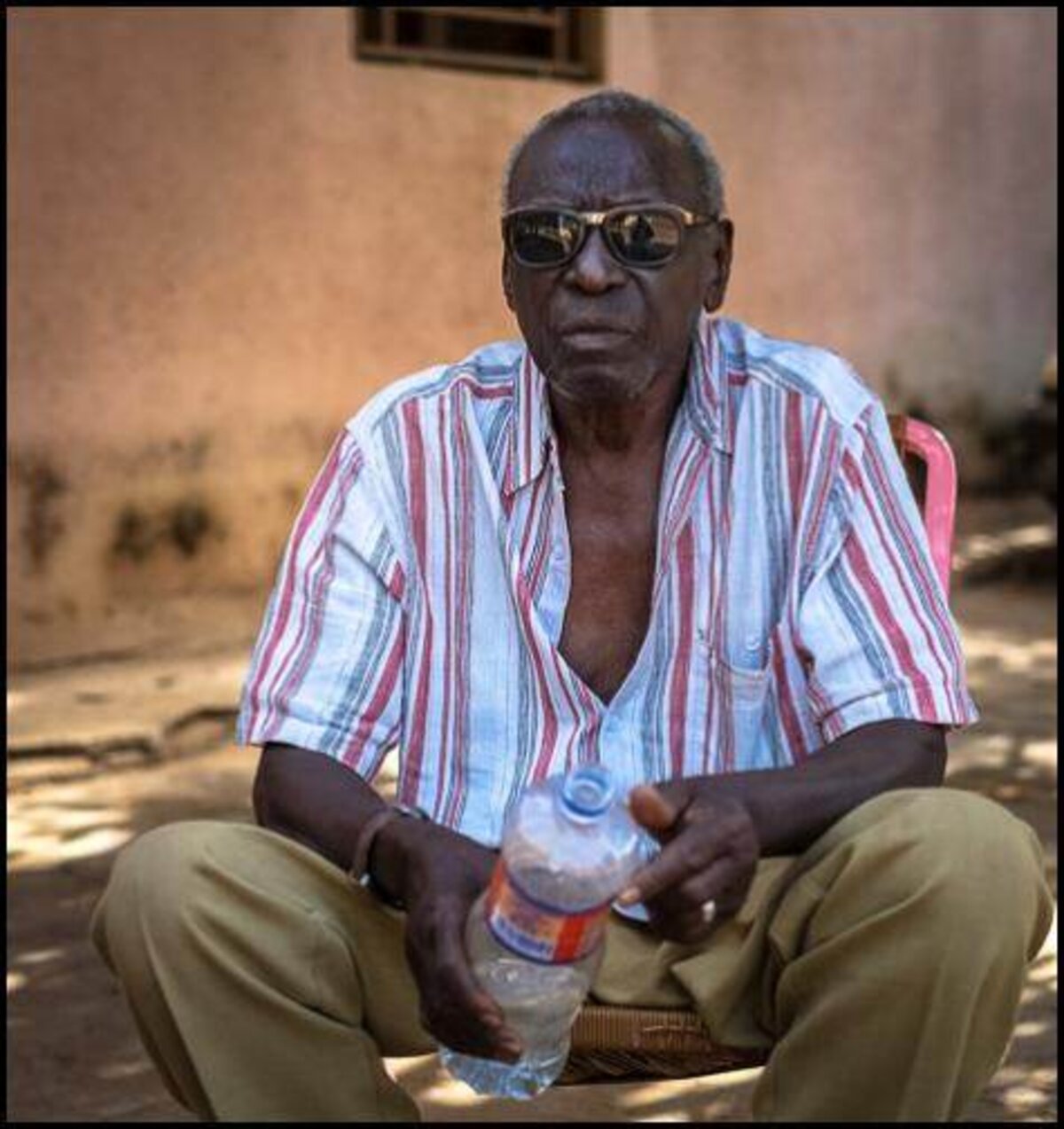

According to his neighbours, 87 year-old Arounata Diallo is the doyen of their district that lies at the centre of the Malian capital Bamako, between the station and the museum. He spends his days chatting to folk, sharing his memories and experiences, comfortably flopped in a plastic chair in the cool of the shade beside a wall of his house.

He has no hesitation when asked for his opinion about the crisis his country has been plunged into. “I was born in 1925 and on my birth certificate is written ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity’,” he says, referring to the motto of the French Republic, Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, and to a time when Mali, independent since 1960, was part of a colonial region called the French Sudan. “Before, the Sudanese were the first of the class, the models,” he continues, “today the Malians are the bottom in everything. After France left, the looters arrived. Our leaders are all brigands.”

Among Malians of Diallo’s generation, there is a widespread nostalgia for the colonial years. The elderly remember with fondness how France built up the country’s infrastructures, educated people, and established a regime of apparent good governance, while the servitude and the racism that came with it is forgotten in the fog of time. But the real surprise is that even the younger generations, including the very young, today turn to the former colonial power with hopes, and sometimes unrealistic expectations, despite the fact that Mali has, over the past several decades, become distanced from France.

Without any doubt, the French military intervention in Mali, launched on January 11th, has radically changed the nature of relations between the two countries. During conversations with hundreds of people from all walks of life in Bamako earlier this month, both in chance encounters and organised interviews, everyone, without exception, praise French President François Hollande’s decision to send soldiers to liberate the north of the country from the control of Islamist groups and to chase the Jihadists beyond its borders.

The Malian and French flags are often to be seen flying together in the streets and on vehicles. There are future fathers who promise to name their offspring ‘Françoishollande’. In Bamako’s principle street market, stalls sell cloths printed with images celebrating the Franco-Malian alliance, showing a dove and the face of the French president.

But even if the intervention has been so largely welcomed with open arms, when France saves the day and marches once more on the soil of its former colony, the situation is bound to be complicated. Put simply, does France have a neo-colonial mandate to put Mali back on its feet?

Like Russian dolls, one question hides another, and none can be easily answered. After having restored the territorial integrity of the country, should France then ensure that Mali does not fall into the ditch of bankrupt states? Must it oversee the proper organization of future political elections? Should it involve itself in encouraging new candidates to replace the aging and corrupt political class, and make good governance a priority? Must it guarantee security throughout the country? Should it attempt to enduringly settle the problems in the north of the country?

In the view of both the Malians themselves and foreign observers present in the country, the state will collapse again as it did in 2012 unless significant political, administrative and military reforms are carried out. The crisis in Mali should prompt other African states to ask just what have they achieved with their independence, some fifty years after the ending of colonial regimes, as much as it also poses a challenge to France to define the manner in which the former colonial power intends to help the country, without profit or manipulation.

François Hollande has pledged to end the system known as Françafrique, the name given to the corrupt and paternalistic ties France has long maintained with its former colonies, including secret and profiteering dealings with dictatorial regimes. While a number of his predecessors made similar promises to no avail, Mali presents Hollande with a rare opportunity of re-writing France’s relationship with French-speaking African countries. But he also finds himself in danger of being lumbered with the responsibility for a rudderless country that France will be bound to finance and support for decades ahead.

'Every African leader must say no to France'

Anthropologist Birama Diakon works from a barely-furnished office in the Malian Ministry of Tourism, where he is in charge of developing tourism in the south of the country, a mission that he admits is far from simple in the current context. “It hurts me to say this, but France is obligated to put its nose in Mali’s affairs,” he comments. “We are humiliated, but what can we do? Even the Chadians are giving us a lesson and are fighting [to free] our territory. Mali will be a country placed under guardianship. If it is not that of France, it will be that of the European Union.”

“After all that France has done, it cannot accept that that be undone,” adds Diakon. He says concurs with the sentiment expressed by one of his friends that “one does not philosophise about the intentions of one’s liberator”.

Many Malians insist that the price French soldiers have paid in lives lost – five military personnel have been killed since the start of the intervention – means that Paris is now too involved to withdraw completely once the military offensive is over. Others raise the notion of a “colonial debt” that leaves a moral requirement for France to save the country from Islamist control.

“France has a particular responsibility,” comments Christian Rouyer, France’s ambassador to Mali. “It strikes me as difficult to shirk it.” But, repeating the message of the French presidency and foreign affairs ministry, he quickly adds: “We earnestly call for a United Nations stabalisation force that will take management of both security on the ground and the reconstruction of the Malian state.”

Indeed, the idea of a close France-Mali tandem has little appeal among the ranks of the elite of Bamako. Political affairs specialist Mahamadou Diawara underlines that in this region of West Africa, France has had particularly complicated relations with Mali. “For the Malians, Modibo Keïta, the hero of the independence struggle, chased France away, and all of his successors have placed themselves in his footsteps. [Former Malian President] Moussa Traoré opposed [former French President François] Mitterrand, [former Malian President] Alpha Oumar Konaré opposed [former French President Jacques] Chirac, and even [the last Malian President] Amadou Toumani Touré, despite being a conciliator, was opposed to [former French President Nicolas] Sarkozy on the question of visas. At given moments, every Malian, and even African, head of state has to say ‘No’ to France.”

Moussa Mara, 35, is the mayor of a district of Bamako, and a future candidate in the presidential elections due in July. Educated in France, he is one of the new generation of politicians that many observers hope will take over power from the discredited old guard. “In French interests, it would be better that it is the UN that takes matters into hand very swiftly,” he says. “That would avoid all the accusations of colonial influences.”

'Our destinies are linked together'

However, the history of UN missions in Africa is “not brilliant”, observes one European ambassador to Mali, whose identity is withheld here. “What’s more, peace-keeping troops are not made for anti-terrorist missions,” he adds. The criticism, pronounced by those who cite the results of UN missions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or Sudan, is rejected by France’s ambassador to Mali, Christian Rouyer. “The situation in Mali is not that of the DR Congo or Rwanda,” he argues. “There needs to be a mandate adapted to Mali.”

This implies making a significant investment in Mali, beyond that alone of sending of peace-keeping forces, one that is focussed on the many areas of activity that have either collapsed or were never properly functioning, including the political system, the public administration services, the economy and the army, and also a redefining of the relations between the north and the south of the country.

Another potential partner is the European Union. While EU member states have shown reluctance to provide troops in support of the French-led offensive against the Islamist groups, or even to assist in the training programme for the Malian army that is due to begin in April, the EU delegation to Bamako has already begun freeing-up the assets it froze after the March 2012 coup d’état. The EU will also provide an exceptional emergency fund of 225 million euros to help rebuild basic services provided by the state. Given that more than half of Mali’s national budget is provided through international aid programmes, the EU’s contribution is crucial.

There is, however, an inherent problem in that every new injection of financing passes through a system with an established network of people and institutions with the risk of repeating the corruption and vote-catching antics that have been widely denounced in Mali for years. Beyond the accusations that no-one can prove, Mali is nevertheless one of the very rare countries in which The Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria discovered part of its funding was embezzled in a scam organised within the health ministry. While one of the ministry’s senior staff was charged and tried for corruption, the health minister has never been investigated.

So just how can Mali be helped forward without reproducing the mistakes of the past? How can an outside influence push for its system of governance to be reformed, and its political class renewed, without creating an impression that such moves emanate from a neo-colonial approach? That is today the challenge for France, and more specifically François Hollande, and is no doubt one which will tomorrow be placed before the international community. “I am afraid that if France does not support the idea that something new must be brought to the country, we will all slip under the carpet and there will be another serious crisis within four or five years,” says Violet Diallo, a British-Malian social worker who has worked for some 30 years in the development sector.

“To all those who argue for a rupture [with France], I tell them that we are officially independent, but not politically so,” argues Moumouni Soumano, a teacher at The School of Law and Political Science of Bamako University. “Our political system, our way of thinking, our language, our republic, all of that comes from France. We must stop being hypocritical. We must admit that our destinies are linked together. Which should not stop us from inventing a new relationship."

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse