According to figures released by the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritime département (equivalent to a county) in south-east France, 1,178 foreign nationals were arrested for illegal entry into France between August 10th and August 16th. Among them were 600 Sudanese, 150 Afghans, 110 Pakistanis and 110 Eritreans.

Two thirds of those arrested were sent back to Italy, after spending several hours at the French border post of Menton-Saint-Louis, situated on the strip of Riviera coast that separates the two countries. “It is the second most important week in terms of arrests after that of June 8th to 14th,” said sub-prefect Sébastien Humbert. During that week in June, a total of 1,548 foreign nationals were arrested in the region and deported.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

At the rail station in the Italian coastal border town of Ventimiglia, the Red Cross centre has been busy helping stranded migrants ever since France beefed up its blockade of the border at the beginning of June. Every night, between 150 and 230 migrants, mostly young men, sleep at the centre on camp beds. “They come from southern Italy, they stay a few days, then try their luck at the border,” said Fiamma Cogliolo, from the local branch of the Italian Red Cross (Croce Rossa). “Every day, 20 to 50 return, rejected by France.”

The process is now so regular that a Red Cross van regularly picks up the blocked migrants to bring them back to the station at Ventimiglia, a distance of about ten kilometres. “That saves them coming back by foot,” said Cogliolo.

From time to time, the Italian police in Ventimiglia send some of those returned from France further south. Sam, a 21 year-old Eritrean, said he was arrested in early August on a train at the small railway station of Menton-Garavan, on the French side of the border. He said he was then taken by bus, along with 23 other Eritreans and Sudanese, to the Italian port of Genoa, from where they were to be sent by plane to the port of Bari, on the Adriatic coast in the heel of Italy. “In the bus we were handcuffed,” recounted Sam, a tall and slender man. “The Italian police closed the curtains and they hit us on the arms with electric truncheons because we refused to take the plane.”

According to Sam, the police in Bari scanned the retinas of several of the migrant group and tried to take their finger prints by force. “I cried, I didn’t want to,” continued Sam. They threatened us. ‘We saved your lives in the Mediterranean, if you don’t want to do the finger prints you will return to Libya’. We told them, ‘we came to find democracy but, if there is no democracy, why not?’” Sam said he was placed in a migrant camp overnight from where he escaped with two others and returned by train to Ventimiglia. “I couldn’t have imagines that that would happen in Europe, I thought it was a democracy,” he added.

On August 10th, a group of about 100 Sudanese and Eritreans mounted aboard the last train leaving Ventimiglia that day, at 10.40 p.m. for Nice, on the French Riviera. They were arrested at the train’s first halt on the French side of the border, at Menton-Garavan, by CRS police officers, (most usually employed for riot control), and returned to Italy.

The police at Menton-Garavan, according to sub-prefect Sébastien Humbert, check “all trains which stop, from the first to the last”. Despite the denials of the Alpes-Maritime prefecture, Mediapart has witnessed, during five train journeys into the station since June, that mostly only passengers with black or dark skins are targeted by the controls.

On the night of August 10th, about 30 migrant rights activists, mostly Italian, gathered outside the border post at Menton-Saint-Louis where the migrants arrested at the Menton-Garavan rail station had first been sent. Reinforcements of riot police from the French gendarmerie – the gendarmes mobiles – were called up and moved the activists to the Italian side of the border. Subsequently, 18 members of the Italian migrant defence group No Borders were arrested and six were given banning orders by the Italian authorities from entering Ventimiglia. The orders are delivered under an arbitrary administrative power, called Foglio di via, which was established for situations threatening public order, and can be applicable for a maximum of three years. In a statement issued after the orders were served, the six activists vowed that “to ban us from access to a site will not prevent us from continuing to fight”, adding: "We will continue to be beside those who travel. From Lampedusa to Calais, from Chios to Ceuta and Melilla. We will be there where the racist and police infamy of deportations and arrests perpetuates.”

On the French side of the border, the events that night of August 10th saw three people of French nationality arrested and held for questioning on suspicion of “resisting the passage of vehicles”. One of them was a student journalist who was filming and photographing the scene. “I refused to show my photos to the police, so they threatened me, then placed me flat-down in the car and went at me in a group of four to take my video camera and stills camera,” recounted Alexis (last name withheld), 23. “When they gave it back to me, they had erased everything. It is a little ironic on the part of the French police which is blockading a border to accuse us of blocking the circulation.”

Alexis was able however to recover his video recordings. These show (see above) the activists peacefully blocking the road while singing, before they are pushed away by the gendarmerie officers firstly in a careful manner and then with brutality. None of the three French arrested that night were charged, because of what the Nice public prosecutor’s office said was a lack of “sufficient” evidence.

'After this border will be another, and another'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

About 50 migrants have set up a new camp site of tents under a viaduct on the Italian side of the coastal border. Activists with the Italian migrants’ rights defence association No Borders report a growing presence in the area of Italian plains clothes police from the Digos-Divisione, an intelligence gathering branch of the Italian interior ministry. At the rail station in Ventimiglia, where the Red Cross centre is situated, it is now impossible for journalists to reach the camp without special accreditation delivered by the administrative authorities in the town of Imperia, some 60 kilometres away.

At the beginning of August, a Nice-based association called Au Cœur de l’Espoir (At the Heart of Hope) which organises practical help for stranded migrants was prohibited by the Italian authorities from distributing meals at the entrance of the rail station in Ventimiglia. “The conditions have become harder even for French associations, and the camp at the border is controlled much more” said Cathie Lipszyc of Amnesty International. “You see lots of Italian police cars pass by. The activists are clearly under surveillance.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

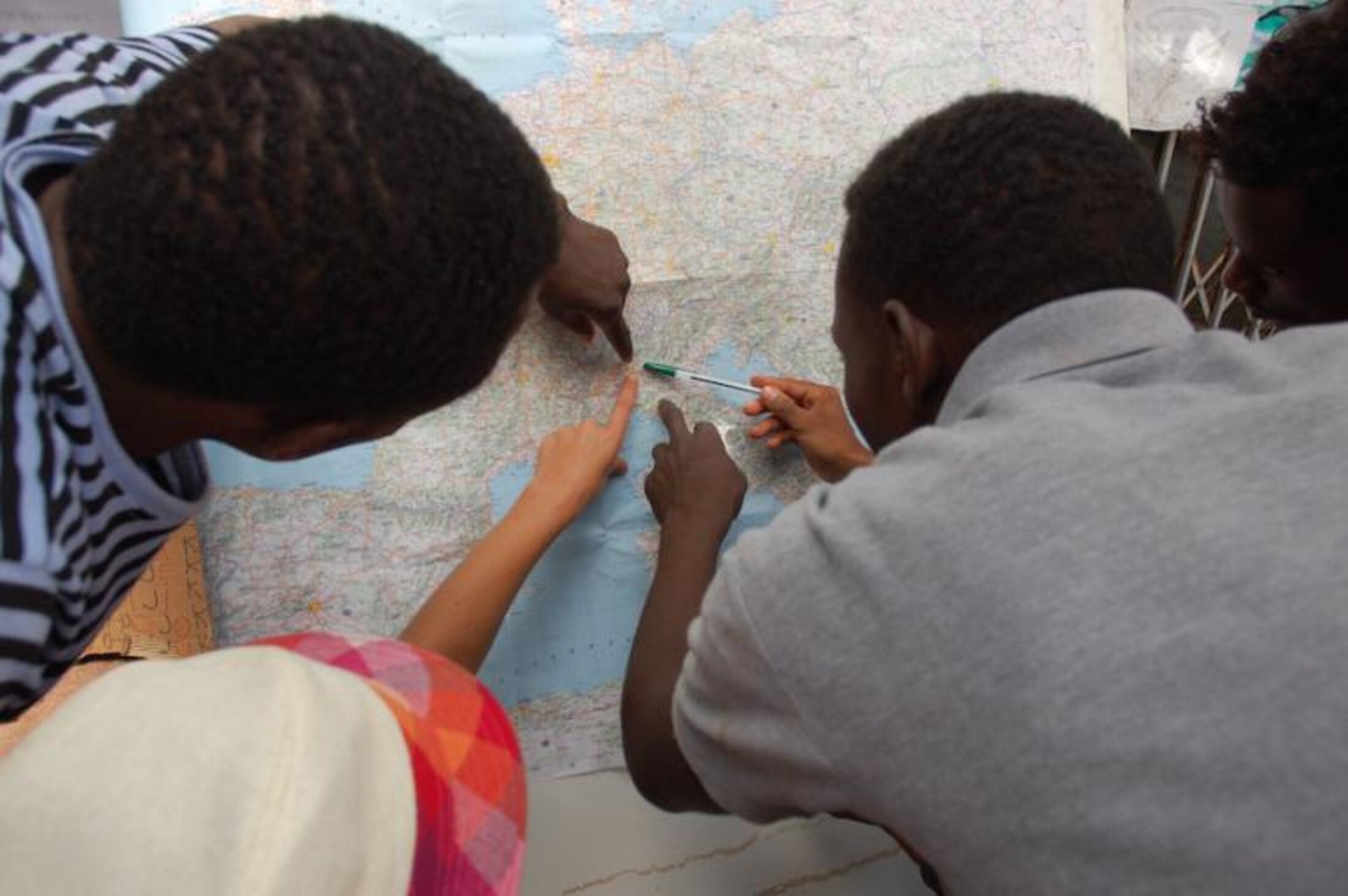

Renamed Presidio, the migrant camp in Ventimiglia (which has a Facebook page) is a remarkable project of cooperation between migrants and activists. Every morning, activists provide language lessons in French and English, and also in geography, with maps of Europe and the Riviera region, with the aim of allowing the migrants to gather their bearings and to subsequently chart their own paths. “People arrive every day, they just want to cross the border,” said a young Italian woman activist, whose name is withheld. “But we explain to them that after this border there will be another, and another. The whole of Europe is an immense border. So it’s important to inform them of their rights, of how to behave, the most racist places to avoid, and so on.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

In the evening, after the general assembly meetings, out come guitars and a pizza oven (which already served during camps outside the 2001 G8 leaders meeting in Genoa). With the new academic year looming in September, the students among the activists present will soon begin heading home. “But we don’t think about that, we will stay as long as there are migrants arriving,” said Anna, 63, the doyenne of the camp who, present at the site since June, has become nicknamed ‘Mama Africa’.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article is available here.

English version by Graham Tearse