Robert Ménard, co-founder of Reporters sans Frontières (RSF), is proving something of an embarrassment to the internationally-renowned French NGO for press freedom, better known in the Anglophone world by the title Reporters Without Borders, as it prepares for its 30th anniversary next year. For Ménard, 60, has just been elected mayor of Béziers, in south-west France, on a ticket backed by the far-right Front National (FN) party.

To shed light on this maverick figure in the French political and journalistic landscape, Mediapart interviewed several former RSF officials and members, most of who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Hervé Deguine, whom Ménard has described as the person closest to him during his years at RSF, did not return our calls, while Ménard himself ended our interview with him after just 20 minutes, accusing Mediapart of “bad faith”. Mediapart contacted him shortly before the municipal elections that saw him elected Mayor of Béziers on March 30th.

"You can go keep your questions, you sweat bad faith, I know Mediapart,” he said. “You want to have a go at me, the only thing you find you have to do on the eve of the elections, it’s going back over the years of Reporters sans Frontiers, not to talk about – because you wouldn’t – the marvelous combat that we led. I know in advance what you’ll write […] I’m telling you, I do what I want with you, I already have the politenessof answering you, because I couldn’t give a damn what you write.”

Some RSF members fear that Ménard's association with their organisation now taints its image, while RSF's official position is that he and the NGO are quite separate now. "He carried and represented the organisation for 23 years,” said Christophe Deloire, RSF's current general secretary. “He has held no post since 2008 and has no official contact. He belongs to the past."

Alain Le Gouguec, chairman of RSF's board, says the organisation wants to talk about Ménard as little as possible. "It has been very difficult for us. We want people to stop associating our actions with him."

However, that seems unlikely. When Ménard announced in May last year that he had obtained precious FN support for his bid for the Town Hall in Béziers, the AFP press agency ran the headline: 'Robert Ménard, formerly of RSF, becomes a Front National candidate'.

"It takes time to lose the label," Deloire said. "But we are not rewriting the past, I'm not going to delete him from the photo like Stalin." RSF, he added, is neither right- nor left-wing, and is not, he said, in the business of condemning a vote for the FN. But last spring, RSF did vote unanimously to withdraw Ménard's title as RSF International President of Honour. "He was furious when he found out. We did not announce it publicly," said an RSF member who asked not to be named.

Some have gone further. In June last year, eleven former RSF members, including former general secretary Jean-François Julliard, published an open letter to Ménard published by French daily Libération, in which they vowed to oppose him. They said they had respected Ménard and had hoped against hope that his deviation to the far-right was a mistake or a misunderstanding. "Each of us […] will fight your extreme right-wing ideas in their own way," they wrote.

Vincent Brossel, who joined RSF in 1999 and was the head of its Asia bureau until 2010, said Ménard had always detested moderates and liked extremes. "But he committed himself to a limitless defence of freedom of expression, excusing extremes, in a spiral of radicalisation in which we cannot follow him," Brossel said. Another former friend from Ménard's RSF days said he had become indefensible. "You leave us in the shit, all these people who campaigned for you," he said, addressing his remarks to Ménard.

Ménard retorted that "if I had been supported by the [Editor’s note: the alliance of radical-left parties]Front de Gauche, which supported the worst enemies you could meet every day in China, would they have written an open letter?" He told Mediapart he had “no far-right references, that is idiotic.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

When Ménard founded RSF he certainly seemed at an opposite pole to far-right ideology. His former comrades described him as having had a rebellious youth. He was a member of the Trotskyist Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire (LCR) for six years, then joined the left-leaning CFDT trade union and then the Socialist Party, which he left in 1981 – when François Mitterrand was elected as France's first Socialist president.

Ménard would refer to his "friends" Daniel Cohn-Bendit and LCR founder Alain Krivine, both leaders of the May 1968 protests, and Noël Mamère, a prominent French ecologist and former TV journalist and anchorman, who were regularly invited to RSF, according to another leading former member. This person, who asked not to be identified, said he had "always believed that Robert was on the Left because his frame of reference was 90% people on the Left".

This was how Ménard was viewed, at least publicly, until 2007, when he declared to his RSF colleagues that he would "proudly" vote for centre-right candidate François Bayrou, in that year’s presidential election, in the first round of voting. "In the second round he voted for [Nicolas] Sarkozy. He thought he would follow a different policy on human rights in China and Russia. He soon realised this was not the case. But Robert gets disappointed quickly," said this former RSF member.

Ménard blames the press for misunderstanding him for so long. "I had no longer been on the Left for a long time, simply journalists cannot imagine for a second that you can defend freedom and human rights if you are not on the Left," he said, adding: "I changed because the world is changing." He declined to situate his position in terms of Left or Right.

In the 2012 presidential election he voted for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, a Gaullist, Euro-sceptic politician who broke with Sarkozy in 2007 and founded his own party, Debout la République, which calls for France to leave the euro. Ménard said, however, that his vote was despite Dupont-Aignan's views on Europe. "I don’t have a party with which I am in agreement,” he said. “I am running a campaign that is neither on the Right nor on the Left."

Tracing back, there were warning signs in those portraits former friends and colleagues paint of him. He “had disturbing ideas, but he wasn't someone on the far-right,” said Brossel. A former friend who declined to be named remembers: "In discussions he would suddenly throw in something off the top of his head and say, ‘but what do you think?’ He wanted to generate a debate, for us to contradict him. We did not see the danger. We were taken up with other things, we held on to what we thought then was the essence of RSF. Perhaps we were wrong."

Another former RSF member said that several people thought this behaviour was no more than a provocation on Ménard's part and that he did not believe in what he said, but none of them could imagine him being drawn to the FN. "He never talked about [then FN leader Jean-Marie] Le Pen, religion or homosexuality as he did after RSF.I only remember that in his justification of the death penalty 'in certain cases' he always cited [convicted Belgian serial killer and paedophile] Marc Dutroux," this person said.

Holocaust deniers and gay fish

Several ex-colleagues say that perhaps Ménard's change of camp began in 2000 when he met Emmanuelle Duverger, now his wife, who is a legal expert and a practising Catholic. Ménard himself admits to her influence but said this was not a turning point for him. "When I met her she was in charge of Africa at the International Federation of Human Rights,” he said, adding with irony that this was hardly all that far from his own concerns at RSF.

Former RSF friends question this. "He never used to talk about religion and he has become very happy to take their daughter, who goes to a Catholic school, to Mass," said one. "He has swung to the other way of thinking. He started to see everything through the prism of his daughter - 'if that happened to my daughter'." Another ex-colleague close to the couple said that Duverger encouraged Ménard to "say what he felt, to open the box".

Ménard certainly opened a Pandora's box in 2003 when Holocaust denier Robert Faurisson, repeatedly convicted of denying the existence of the gas chambers, visited RSF's offices. Former colleagues describe this as having been a huge shock. "That gave rise to a rowdy meeting, we told him it was not acceptable," remembered Brossel. "For half a day some refused to work and threatened to go on strike." Ménard replied that the matter was his responsibility and nothing to do with RSF, Brossel recalled. "I'm just saying that this gentleman has the right to express himself ", he remembered Ménard as saying.

When Mediapart questioned Ménard about this, he became heated. "This is four minutes in the history of Reporters Without Borders, it is true that this is important,” he said in ironic tone. “Faurisson came to RSF, he asked to see me. I was surprised to see him and rather uncomfortable. I said to myself, do I leave him at the door or do I let him in? He came into my office and said to me, 'will you defend me?' I said, 'No, I defend your right to express your beliefs'."

The publication in January 2003 of a book co-authored by Ménard and Duverger, La Censure des bien-pensants (‘The Censorship of the Well-Meaning’), was a wake-up call for Ménard's ex-colleagues. Faurisson's visit to Ménard came shortly after it was published. In it, Ménard and Duverger called for the repeal of the Loi Gayssot (1), which outlaws racist and anti-Semitic acts, saying it was an "iniquitous text, unworthy of a democracy".

Their fourth chapter, entitled "Faurisson should be able to speak", begins with these words: "The revisionists are right. They are the objects of a real witch hunt, victims of what should really be called a thought police, a misappropriation of the law." The authors did qualify this by saying "That their assertions are contradicted by everything we now know about, the Final Solution is not in question here," but they go on to denounce "the treatment that the French justice system reserves for them", calling it a "manhunt" aiming to use the law to muzzle people considered to be out of line.

"I never defended Faurisson. I wrote a book in which I condemn the Commemorative Laws [1 -foot note bottom of page]. That has nothing to do with what you think of the underlying argument," said Ménard, for whom his book was "a synthesis of what RSF was saying". He positions himself as an advocate of the First Amendment of the American Constitution and as a "Voltairian" whose aim is to "defend the right of people to express their point of view whatever it may be," and mocks those who want freedom of speech "but only for their friends". (Voltaire's often-cited maxim was: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.")

In this vein, the book takes 165 pages to list what the authors call "censorship" of things deemed to be racist, sexist, negationist or obscene, including convictions for revisionists or a "paedophile joke" which broadcasting watchdog CSA (The Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel) had in its sights. It evokes the controversy when Abbé Pierre, the late French priest who created a nationwide organisation dedicated to helping the homeless, said the French press was inspired by an international Zionist lobby. It argued that expression had become "taboo", while it also denounced "a new moral order right into literature and fictional characters" and an "ostrich" policy " on sexuality.

Ménard's tolerance found its limits, however, when in 2010 he opposed schools showing children aged 9 to 11 a 20-minute cartoon against homophobia that depicts a fish falling in love with another of the same sex. "I don't want my children to see that," he said in an interview on Paris Première TV channel. "Yes, I want my children to be heterosexual."

A former RSF member found Ménard's book revealing. "With this book, not only did we discover ideas we did not know he had, but also that we were no longer in tune with him professionally if he would go that far to defend freedom of speech, " he said, asking not to be named. "That allowed him to defend everything. We did not want to use our energy to serve certain figures - he had begun defending them, like [Alain] Soral and Dieudonné [footnote 2] and was doing things without us knowing.”

Later in 2003, Ménard became so anti-Castro that he approached a part of the Cuban diaspora that some of his colleagues judged to be extremist. Then in 2004 he went to Kiev at the time of Ukraine's Orange Revolution and visited the pro-Russian premier, Viktor Yanukovych, whose authoritarian regime had been widely criticised by human rights organisations. He did not meet the leader of the opposition, Viktor Yushchenko, who had been the victim of a poisoning attempt.

In 2006 his colleagues discovered that Ménard had gone to Lebanon to defend Al-Manar, the Hezbollah TV channel, after an Israeli bombing raid. "Some programmes called for killing Jews, it was a call to murder,” one colleague said. “He replied that to be heard, it was necessary to be on the edge," another remembers. Ménard himself said that he has always "applied the RSF line to the letter – defending someone without sharing their opinions – in China, in Cuba, everywhere."

Then in 2007, interviewed about Al Qaeda's 2002 abduction and beheading of Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl, Ménard appeared to justify using torture on the families of Pearl's kidnappers, saying that Pearl's wife Marianne, who was pregnant at the time, was prepared to do anything to save her husband. "Legitimately, if it were my daughter who was taken hostage, there would be no limit, I tell you, I tell you […]" (A full transcript of the interview in French is available here.)

---------------------

1: The Loi Gayssot was enacted in 1990 and made Holocaust denial an offense. It was followed in 2001 by two laws, one recognising the genocide of Armenians in 1915 and the other, the Loi Taubira, recognising slavery and the slave trade as crimes against humanity. In 2005 another law brought in recognition of France’s colonial role and the cultures of its overseas territories. Together these are known as the Lois Mémorielles, or Commemorative Laws.

2: Alain Soral is a far-right Franco-Swiss essayist. Dieudonné Mbala Mbala is a French comic who is close to Soral. Both have recently been the centre of controversy for their overt anti-Semitism. See more here.

An 'uncontrollable side'

At the time, RSF was funded through several sources. One of these was the sale of photo-albums (handled free-of-charge by France’s press distribution network, the NMPP) and other products, but it also received financing from French billionaire businessman François Pinault, along with French pharmaceuticals company Sanofi-Avantis, the National Endowment for Democracy, a US-based NGO, and the US-based Center for a Free Cuba.

In 2004, RSF received 10,000 euros from Omar Harfouch, a wealthy Franco-Lebanese businessman who Ménard conceded was “a friend of Colonel Gaddafi” but who he said was also a friend for RSF “who always answers ‘present’ when called upon”.

In 2007, Ménard joined forces with Sheikha Mozah, wife of the Emir of Qatar, to set up the Qatar-based Doha Centre for Media Freedom, for which he served as General Director until resigning in June 2009. “He told us ‘it’s an opportunity that must be grabbed, I dictated my conditions’,” recalled a member of the RSF board. “He ended up winning the day.” Ménard later described teaming up with the Qataris as a “pragmatic” move.

“His logic was ‘we don’t care who these people are if they want to give us the means’,” commented Vincent Brossel, who added that at RSF “we didn’t have the right to criticise the media”. Interviewed by French daily Libération in 2008, Ménard insisted “I am not a righter of wrongs of the press”, adding that “my job is to get people out of prison”. To build up RSF he needed funds and coverage in the media, which meant abandoning his sometimes outspoken criticism of them.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

“As a question of principle, Robert talks with everyone, even those he hates,” said Olivier Basille, one of his friends and director of the organization in Belgium, and who worked alongside him on Ménard’s magazine Médias. Some of the old guard at RSF point out that it defended people of all persuasions, and pay tribute to the feat of the small-town journalist who gave the NGO an international reach. “He was looked down upon when he arrived with his southern French accent, incapable of speaking English,” recalled one of them. “He was a general who led his troops from the front, he wasn’t at the back. He spent his time saving human lives by putting his own in jeopardy. He was almost killed in Haiti. He sheltered Tunisian opposition members in his home. In the Tunisia of [deposed dictator Zine El Abidine] Ben Ali, he got thrown out and disgusting things were written about him – ‘paedophile’.”

This same source underlined the “extraordinary operation” Ménard pulled off with his human rights protest during the Olympic torch handing-over ceremony in Greece ahead of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, and the protest campaign that continued in China afterwards -which included pirating an FM frequency. “Thanks to walking sticks [equipped] with miniature transmitters, 20 minutes of messages on freedom of expression were broadcast right in the centre of Beijing. Afterwards, he was threatened with death, his family too [and] placed under police protection.”

Vincent Brossel paid tribute to how Ménard had “battled for months” to obtain a commission of inquiry into the murder of Burkina Faso newspaper editor Norbert Zongo.

“I only obtained the liberation of hundreds of journalists for whom some of your colleagues didn’t even lift a finger,” Ménard told Mediapart. “Call Florence Aubenas, she’ll tell you what we did for her.” In January 2005, Aubenas, then a journalist with French daily Libération, was taken hostage in Iraq, along with her translator Hussein Hanoun Al-Saadi, and was finally released after six months.

“When I travel, I meet people who remember with emotion what RSF and Robert had done for them,” said RSF's current general secretary Christophe Deloire.

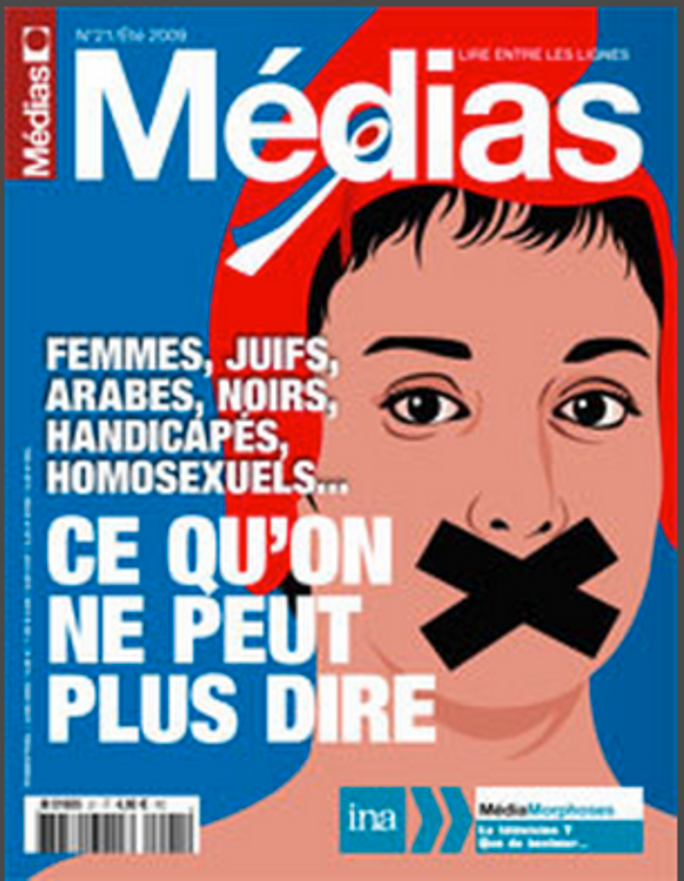

During his last years at RSF, Ménard spent much of his time looking after his magazine Médias, which he edited with his wife Emmanuelle Duverger. The quarterly carried lengthy interviews with former Front National leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, his daughter and the party’s current leader Marine Le Pen, Alain Soral, far-right French writer Renaud Camus, and also Pierre Cassen, founder of the website Riposte and who, Ménard’s magazine recounts in its introduction, “hates Islam”. A former RSF colleague recalled: “He began to place this defence of freedom of expression at the service of just one camp.”

In 2008, commenting his defence of the right of expression for negationists who notably deny the existence of the Holocaust, Ménard told Libération: “I will never again write about that, the ricochet effect of it on RSF was terrible.” In fact, he did continue “about that”, but outside of RSF. He went on to champion the freedom of expression of Dieudonné and the French self-described neo-Nazi and negationist Vincent Raynouard, while attending conferences organised by Identity Bloc supporters in Lyon and at a Paris bar run as a meeting place by far-right activist Serge Ayoub.

During his municipal election campaign in Béziers, Ménard ran as the head of a list of candidates for seats on the council which included six members of the Front National. During a report on the elections, French news website Rue89, while visiting Ménard’s campaign headquarters, came across André-Yves Beck, a former communications director for Jacques Bompard, the far-right mayor of the southern French town of Orange where, beginning with Bompard’s election in 1995, the municipal library was the target of a purge of books about WWII, rap music and racism.

“This direction was predictable, but to see it you had to go back a long way,” commented one former RSF official. Other former colleagues spoke of these signs as being Ménard’s “uncontrollable side”, his “autocratic management” and how he had “personalized” the NGO. He also suggested Ménard's family background was a significant influence.

Ménard’s family had lived in Algeria, when it was a French colony, from the mid-19th century. His father was a Communist, a militant with the CGT trades union (then affiliated to the Communist Party) who was actively engaged with the OAS , a French paramilitary group which in the early 1960s actively opposed President Charles de Gaulle’s granting of independence to Algeria after a long and bloody war. When it became independent in 1962, Ménard and his family left to settle in a village in the Aveyron département (county) in southern France, where they lived close to a camp set up for other French nationals who had fled Algeria, and where a daily ceremony to salute the French flag was held. “With age, he has returned towards his deceased father,” said a former RSF colleague, who said that it was for his father that he accepted the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest award for civil merit, in 2008. “He is psychologically freed from this weight of French Algeria to the point of becoming border-line on Islam.”

Olivier Basille said his friend Ménard now acts out of a “change in function and combat” and not from an ideological evolution. “When you lead an international organization, you put aside your own convictions,” Basille said. “Freed from this post, you express yourself, above all when you aspire to an elected office.” Ménard himself commented in 2011: “I wasn’t questioned about homosexuality when I was head of RSF.”

Nevertheless, he had made known his views about the Front National. In his co-authored 2003 book, La Censure des bien-pensants, he wrote on the subject of the 2002 French presidential elections, when the then Front National leader Jean-Marie Le Pen drew the second-highest number of votes among candidates in the first round to go through to the two-candidate play-off against conservative Jacques Chirac in the second.

Le Pen’s historic success, largely due to the fact that the vote of the Left was unusually split among the many leftist candidates in the first round, caused a political earthquake in France. The Socialist Party called for its supporters to bar Le Pen’s route by voting in the second round for Chirac. In the end, Chirac won with a landslide 82.2% share of votes cast.

In his 2003 book, Ménard returned to the widespread mobilization against Le Pen between the two rounds, denouncing the talk of “the ‘fascism’ that the leader of the far-right supposedly represented”, the emotional cries of “No pasaran” in street protests, and criticising newspapers for becoming “militant pamphlets”, while he also slammed the Front National’s “staggeringly empty propositions” for political change.

Ten years on, it is with the support of the Front National that Ménard now looks to enact change in Béziers.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau and Graham Tearse

(Editing by Graham Tearse)