French finance minister Pierre Moscovici, speaking on radio station France Inter on Sunday, hailed his government’s “courageous” policies, announcing that “never has a government engaged upon such reductions in public spending”. In that he was right, for his ambition to save 50 billion euros in public spending over the next three years raised the curtain on an austerity programme that is unprecedented in France since World War II.

As yet, no-one has taken stock of the effort that this will demand. Within the context of the 1,100 billion spent by the state, local authorities and upon the social security system, the sum of 50 billion euros takes on an abstract sense. Overall, it is received wisdom that there are of course savings to be made, and everyone can think of the building of useless roundabouts, the burden of bureaucracy that regularly sees different public administrations demand several different forms for the one and same procedure, and so on. But these are microscopic examples that fall well short of the target that has been laid down.

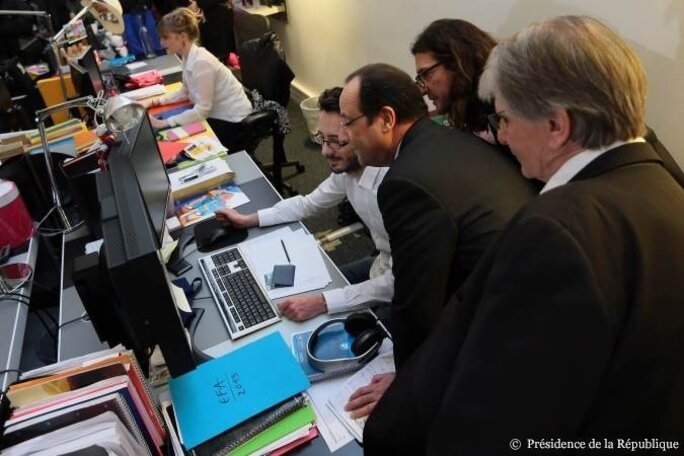

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“France is in a danger zone”, warned Didier Migaud, president of the national audit office, the Cour des comptes, in his presentation of the body’s annual report on Tuesday. The auditors detailed the sectors that should be principally targeted, and a priority was made of both the French welfare system “taking account of its weight in public spending”, and the activities of local authorities. “There must be a change of method in order to obtain the programmed savings,” underlined Migaud.

The recent lies by education minister Vincent Peillon, when he denied that there were plans afoot to freeze the traditional system of automatic promotion (grades based on length of service) for public employees, is an illustration of what is being secretly prepared within the ministries. Gigantic budget reductions are being drawn up, which will see a complete turnaround in France’s social and public systems. Without actually saying so, the government is in the process of engaging on an austerity programme comparable with that put in place by the Spanish government in 2008 and 2009, representing the policies of the Troika – but without the Troika being involved.

Since the beginning of the financial crisis, the terms of the Troika’s policies have now become familiar, and France has already done much to conform to them. A reduction in the number of public sector workers? That is a process that began in 2009 and which has been continued by French President François Hollande despite his electoral promises. A reduction in public sector salaries? The pay index has been frozen since 2010, a move that represents a fall of around 5% in salaries and pension payments.

A shake-up of the state pension system? A new reform was launched under the socialist government of François Hollande, pushing up the retirement age and lengthening the required number of years of contribution payments, making the terms of the French system one of the toughest in Europe, despite a favourable demographic trend. The suppression of regulated professions? A reform is underway for the taxi trade and chemists’ shops.

A programme for a reduction in spending on medical care has been underway for some time, while a reform of the labour laws is underway, notably with the current move to re-organize the system of work inspectors.

After three years of silence, the former Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Zapatero, who was one of the first among political leaders to experiment with these remedies, last year published a book in which he reviewed his government’s actions in dealing with the financial crisis and which many in Spain regard as a period of betrayal. “The question is to know how we face up to competition,” said Zapatero, who was in office from 2004 to 2011, in an interview with Spanish website infoLibre (which has a partnership with Mediapart), published in January. The easy answer, so to speak, is down to innovation, to technology. But they [China, India and Brazil] are in the process of buying it. The Right and the prevailing current of opinion within the economy say ‘Ah, that, it can only be done through a devaluation of salaries, a work market that is almost free for corporations, with no minimum salary, with fewer rights in [labour] contracts, an inexistent collective negotiation [system], because it’s the only way to be competitive’. It is to that argument that [the] Social Democracy [movement] must know how to respond.”

At least Zapatero had the justification that when he took his policy decisions he was placed under intense pressure by both the financial markets and European leaders. Furthermore, he was engaged in something of a real-time experiment. Amid all the panic, no-one really knew what to do. François Hollande doesn’t have that excuse. There is no pressure from the markets, and no threat of an immediate explosion of the eurozone. Ignoring the warning of the former Spanish prime minister, Hollande has not sought a Social Democrat response. Rather, he has satisfied himself by adopting, without great difficulty, the arguments of the business world.

Thus, in the secret meetings set-up at the French finance ministry, an unprecedented austerity policy is being prepared. Entire programmes for supporting the development, investment in and support of the economy, security even, are to be targeted. Even if the government purports to reject any arbitrary policy based on figures only in favour of a profound reflection over its choices and missions, the reverse is suggested by its creation in January of the Strategic Council on Public Spending (Conseil stratégique de la dépense publique), a monthly gathering presided by Hollande and composed of Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault and five key ministers. The state is readying to slash budgets and jobs, in line with the law of figures.

The manoeuvring around the plan to freeze the automatic promotion system of public employees in the education sector (a graded system which affects salaries) is an indication of exactly the same thing. Why does the government want to target the education sector first? Because it represents the largest battalion of public sector employees, and the second biggest single slice of state spending after the financial costs linked to the public debt.

The Spanish lesson

To justify putting in place policies that are so far removed from the promises made during the 2012 presidential election campaign, François Hollande and finance minister Pierre Moscovici stress upon the necessity of reigning in public spending, to maintain credibility with the financial markets and for France to regain its competitiveness.

Behind the recent ‘responsibility pact’ presented by Hollande in January, which broadly offers businesses tax reliefs in return for job creations, is an ideological U-turn that takes one’s breath away. After having for decades defended not only a supply-side policy but also the state’s role of stimulus and support of the economy, the government has now rallied the most free-market vision that considers any spending by the state to be unproductive by nature. This unexpected conversion leads the government to accept a massive transfer to the private sector, seen as being the only actor who knows what is best for the economy.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The about-turn is all the more surprising given that the austerity policies imposed on countries by the EU have fewer and fewer supporters. Souther Europe, submitted to the rigours imposed by the Troika, has witnessed the largest destruction of economic resources in peacetime. Faced with the spectacular collapse of the economies of southern Europe, and which they did not foresee, the international institutions have since felt it necessary to proceed with a critical revision of their theories.

For example, the economists of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have now discovered that public spending is not necessarily unproductive, that the wages paid to public employees served to maintain consumption and demand, that spending by the state could support production and investment. What a surprise!

In a report published in October 2012, IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard highlighted a conceptual mistake that European states made in their economic forecasts – which had been, all the same, accredited by the IMF. These were that for every euro cut from public spending, the cost of economic contraction was just 50 cents. That however, was not what happened.

“Developments suggest that short-term fiscal multipliers may have been larger than expected at the time of fiscal planning,” noted the report, entitled 'World Economic Outlook – Coping with High Debt and Sluggish Growth'. “Research reported in previous issues of the WEO finds that fiscal multipliers have been close to 1 in a world in which many countries adjust together; the analysis here suggests that multipliers may recently have been larger than 1.”

IMF studies today evaluate the multiplier coefficients at between 09 and 1.7. This means that for every euro cut from public spending, the negative effect for the economy can be valued at between 90 cents and 1.7 euros.

The European Commission (EC) challenges the IMF analysis, arguing that the counterproductive effects of austerity measures are over-estimated. It sticks to its old rule policies of internal adjustment and devaluation bear fruit in the end. It cites the supposed success of Spain in support of this, with the claim that after five years of recession the country is seeing a recovery.

What a recovery! Economic activity rose by 0.1% in the third quarter of 2013, after falling 13% over the previous five years. Loans to businesses fell by 19% at the end of last year, with consumption and production also down. The unemployment rate has reached 26%, of which 53% are young jobless. If Spain has recorded its first trade surplus since 1971, it is above all down to the fall in imports. The public debt, which represented 57% of GDP in 2007, reached 93% in 2013 and is expected to rise above 100% this year.

The French government has now signed up to this EC belief in the merits of internal devaluation. How can one exclude that the same causes will not produce the same effects as seen in Spain? That is a question the government has carefully side-stepped. Already, the initial effects of the rise in taxes and spending cuts introduced over the past 18 months have been shown. The economy is at the limit of a recession. In December, industrial output fell again, by 0.3%. Since the beginning of the financial crisis, industrial output has fallen by 16% to the level it was in 2006.

Everything has remained blocked since the crisis began six years ago, and the French economy is paddling water. Consumption is stagnating, investment is at its lowest level since the economic crisis of 1993, and across industry projects are put in hold. Unemployment, meanwhile, has seen a sharp rise. In this context, to decide to cut spending by a further 50 billion euros is to guarantee a collapse of the French economy, or at best a prolonged period in recession.

With his eyes fixed the example of Germany, François Hollande is convinced that, in order to relaunch the economy, France needs first to adopt the same measures that its neighbour introduced between 2004 and 2008. But that is to forget that the Hartz concept, as these have become known, and which saw sometimes drastic adaptations and adjustments to salaries, was introduced when every country in Europe was enjoying growth. It is also to ignore the fact that the constraints of the single European currency are greater on France than on Germany, and the different character of German industry.

The situation today is quite different from that of the mid-2000s. France is introducing increased austerity at a moment when the whole of Europe is threatened by deflation. Even if the word is hardly ever pronounced, it is on everyone’s minds. Far from leading a countercyclical policy against the danger many economists consider to be the greatest, the French government has opted for a pro-cyclical policy. The threat is not only that this will further worsen the plight of the French economy, but also that of the rest of Europe.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse