The bill of law recognising the blank vote (also known as a white vote) as an act of voting was definitively adopted by both the upper and lower houses of the French parliament after a final vote in the French Senate on February 12th, after being largely watered down during its passages before both.

Envelopes containing blank ballot papers will, beginning with this year’s European elections, be considered as blank votes, and counted in a separate category from invalid ballot papers, such as those that are torn up, scribbled over or stained.

However, blank ballot papers will not be provided in the polling booths, and those who wish to vote blank will have to prepare their own white papers – and be careful not to damage them in any way so as not to be counted as invalid. Above all, the blank votes will not be included as an integral part of the official election results (i.e. as an equal element in the total proportion of votes cast, as in a pie chart, which would have reduced the percentage scores of votes cast for candidates).

“This law has the unique aim of better respecting those who, by voting blank, express a choice, or rather a non-choice,” said Jean-Pierre Sueur, the Socialist Party president of the French Senate’s legislation commission.

The new law will not come into effect for the local municipal elections to be held across France on March 23rd, a move which Sueur claimed is for a “purely technical reason”. However, a number of observers interpreted this as a ploy by France’s socialist government to help the Socialist Party retain some support in what is widely forecast to be an election which will see an important swing to the Right.

“We have difficulty in being truly happy, it’s a minimal recognition,” complained Stéphane Guyot, head of the Blank Vote Party, (the Parti du vote blanc) which will field candidates in seven of the eight French constituencies in the European Parliament elections this coming May.

Ever since 1852, French electoral law has included blank votes among invalid votes. These were never included among the effective results of elections, in which – and even now after the adoption of the new law - only those designating named official candidates are included.

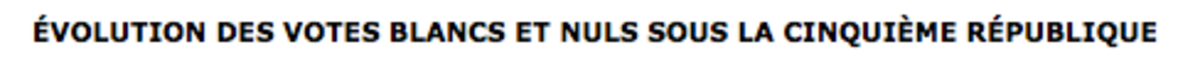

The total number of blank and invalid votes in elections has seen an upward trend since the beginning of the current constitution of the Fifth Republic in 1958 , showing a peak during a number of referendums. These notably include that of 1972 on the issue of enlarging the then-European Economic Community (which has since evolved into the European Union) and another in 2000 on reducing the then seven-year term of presidential office to the current five. In municipal elections in 2001, a ‘List for the White Vote Party’ (now the White Vote Party) caused surprise by attracting as much as 8% of the vote in the Normandy town of Caen.

For the past 20 years, the cause for recognition of the blank vote has become something of a hobbyhorse for a number of politicians apparently persuaded that it represents a means for filling the widening gap between voters and political leaders. Since 1993, Members of Parliament (MPs) from both the Left and Right have proposed 26 bills on the subject. Centre-right veteran François Bayrou made recognition of the blank vote part of his presidential election campaign manifesto in both 2007 and 2012.

“The blank vote is a civil act,” said centre-right MP François Sauvadet, who was behind this latest and successful bill. “It is distinct from abstention, the voter having gone to the polling booth and, on the opposite, expresses a choice, a political will to take part in the poll to express their refusal to choose between those candidates running.”

Sauvedet believes that recognition of the blank vote will discourage abstentions and reduce the numbers voting for extremist parties which, he says, “is often a vote of rejection”.

Socialist MP Jean-Jacques Urvoas, head of the law commission of the National Assembly, the lower house, agreed. “It is the considered act of he who wants to indicate their attachment to the democratic process and a mistrust, at the least, of the candidates or options presented before him to choose from,” he said.

'Democracy is choosing a candidate'

In rural areas, which the turnout for elections is traditionally and proportionally higher than in urban areas, the blank vote is used by those who might otherwise abstain but who would be badly looked upon among their community if they didn’t go to vote. But overall, few expert observers subscribe to the views of Sauvedet and Urvoas that the new law will suddenly reverse abstentions.

“The sociological profile of people who use the blank vote and [those who are] abstentionists is very different,” commented Adélaïde Zulfikarpasic, a research director with polling agency LH2 and one of the rare researchers specialized on the subject of abstention. “The distinction between them is very closely correlated with the level of integration into society. The typical abstentionist is young, working class, lives in a town, turns his back on political life. The blank voter is aged between 25 and 45 years, but he is integrated in active life, has a level of education that is pretty high, and an interest in politics.”

Joël Gombin, a researcher specialised in electoral behaviour and trends with the Université de Picardie Jules Verne, is similarly sceptic. “All of this reflection comes from a quite naive or idealistic vision of what a voter is,” he said. “The well-informed voter who reads all the [policy] programmes and who rationally considers that he will vote blank because he’s unhappy with the existing political offer exists, but is marginal. For politicians, recognising the blank vote is less costly than calling the political system into question.”

Patrick Lehingue is a professor of political sciences with the Université de Picardie, and is the author of a recent book on electoral behaviour Le vote, Approche sociologique de l'institution et des comportements électoraux. “The recognition of the blank vote is symbolic, and what is symbolic in politics is never to be despised,” he said. “But I really doubt that this will change the abstention rate by one iota. To think that a change in the rules of law in itself modifies social phenomena is pure legalism. To change things would need truly revolutionary propositions, such as no holding of multiple posts of public office.”

The pro-blank vote activists argue that only the inclusion of the blank vote as part of the election result – i.e. that has a pie-chart like share of the result and therefore also an effect on the relative share of candidates – will have a true effect on political life. “That would be a full and total recognition,” commented Stéphane Guyot, of the Blank Vote Party.

The consequences of that would be significant. France has a two-round voting system - by which all candidates stand in the first and only the two who attract the highest number of votes move on to the second - for its presidential, legislative and local council elections. Technically, and at present, no-one could be elected if the blank vote attracted the majority in the second round.

But it would more likely make it difficult for candidates to have an absolute majority, as they necessarily must at present, in those many constituencies where traditionally the results are a close call. For example, where just two opposing candidates in the second round might now see a 48% - 52% result, this could conceivably become 47% - 45% alongside 8% in blank votes.

As for referendums, the projects proposed could only be adopted if the vote in favour outweighed both the ‘No’ and blank vote. It would also modify the amounts of public financing received by political parties, which is clearly unwelcome for those of both the Left and the Right.

If the blank vote was considered as a part of the results in the two-round presidential elections, whereby at present it is only the candidate who attracts an absolute majority who wins the second round, one can imagine similar problems. In 2012, François Hollande drew 51.6% of the vote; but if one included the amount of blank and invalid votes that were cast (and jointly considered invalid), his score would have been reduced to 48.6%. In 1995, Jacques Chirac was elected president with a 52.6% share of the second-round vote, but this would have been 49.5% if the blank and invalid vote was included in the overall score.

“Democracy is to choose between candidates,” said socialist Senator Jean-Pierre Sueur. “The vote must designate a project or a candidate, it must express a position.”

There is also the question of what defines an ‘invalid’ vote, and whether these also should have a right to be recognised like the blank vote. In practice, the true distinction is unclear, and invalid votes include those cast by some who believed they were voting blank (such as those placing several names of candidates, or ripped up names, or former candidates, in their vote envelopes). “The invalid vote is often the expression of something,” commented Adelaïde Zulfikarpasic. “To write ‘Hollande resign’ on a voting form obviously has a meaning.” Professor Patrick Lehingue agreed: “Votes which speak [of something] have for decades been considered as invalid.”

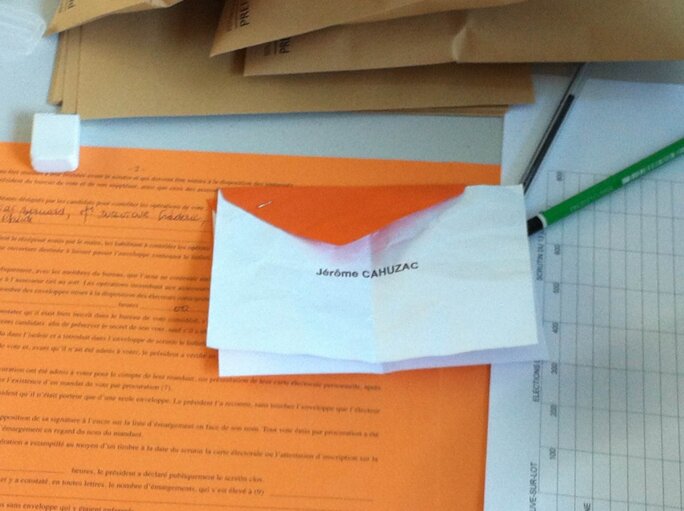

Enlargement : Illustration 3

During the parliamentary by-election that followed disgraced former socialist budget minister Jérôme Cahuzac’s exit from parliament in 2012, his Socialist Party successor candidate took a severe beating at the hands of both the far-right Front National party and Cahuzac’s diehard supporters who cast invalid votes – voting forms with his name on them.

There is every chance that in the current context of a left-wing government which has become highly unpopular even among its own camp, the upcoming local and European elections will see a flurry of ‘invalid’ votes which carry their written messages of frustration. Just as likely is that the blank vote will offer, during the European elections, a refuge for some of the traditional but now disillusioned supporters of the Left who reject abstention.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse