French writer Tereska Torrès, best-known in the English-speaking world for her novel Women’s Barracks, died in Paris on September 20th 2012 at the age of 92. She was the author of 14 books, the first written when she was just 17 years-old, many of them translated into English by her second husband, the late US writer and journalist Meyer Levin. Torrès joined the Free French Forces in London when she was just 19, lost her first husband, Georges Torrès, in an air battle over the Vosges Mountains in 1944 and witnessed Léon Blum’s tearful hesitation over being asked to lead France in the wake of the Second World War.

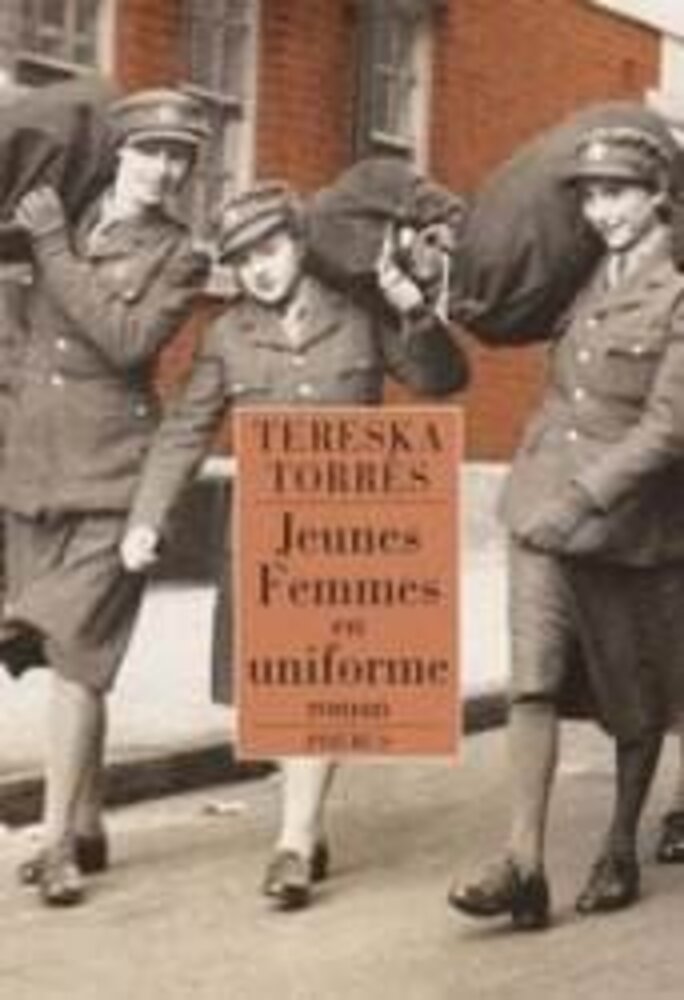

But perhaps the strangest chapter in her eventful life was how her book in English based on her experiences as a woman soldier in wartime London, ‘Women’s Barracks’, became a bestseller and a pillar of lesbian pulp fiction, almost against her will. Championed in the United States, the book remained largely unknown in France. In 2011, she finally completed a modified French version of the book, which was published under the title ‘Jeunes Femmes en Uniforme’, when Antoine Perraud interviewed her about her multiple lives and extraordinary relationships, which we republish here.

-------------------------

Tereska Torrès has lived her many lives so well over her 90 years - she turns 91 in September - that her multiple identities mingle without discord. She says she feels "a bit Polish, a bit Jewish, a bit Catholic, a bit American, a bit Israeli and extremely French."

She became a celebrated writer when her book, ‘Women's Barracks', published in New York in 1950, became a bestseller for its description of the strange alchemy of desire and danger in wartime London, including some lesbian scenes between members of the French Free Forces' Women's Corps.

It sold four million copies, was translated into a dozen languages and was cited by the House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials amid the political and moral crackdown of the McCarthy period. On being re-issued in 2003, feminist and lesbian groups hailed it as a liberated and pioneering work.

All of that is a far cry from most of her life experiences, in which loss, persecution, identity and political commitment are recurring themes.

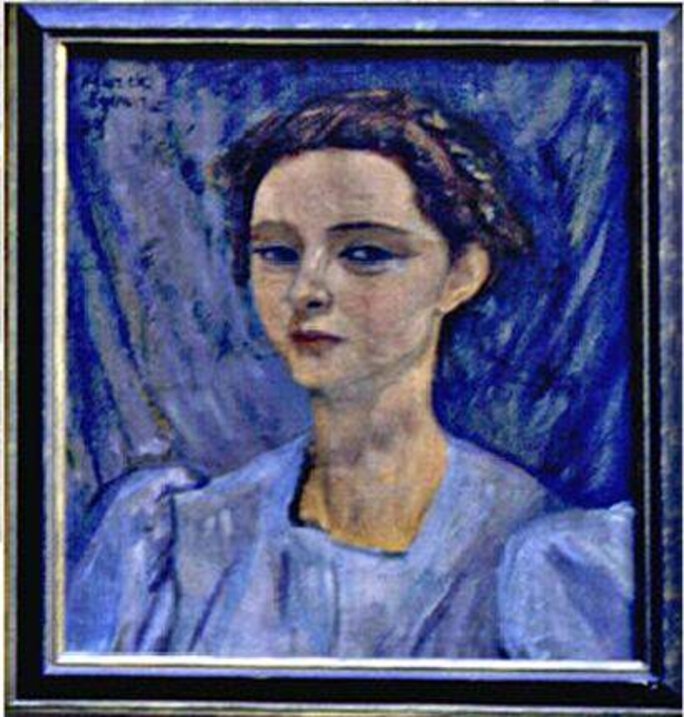

She was born to a Polish Jewish couple in Paris, painter and sculptor Marek Szwarc and Eugenia Markowa, known as Guina, and she still lives in their workshop (see video above). She speaks of their love for each other with great tenderness.

And she recounts without pathos how her grandfather in Poland, a book collector, stood up to a Nazi squad which had come to burn his books. "You will not touch a single one of my books while I am alive!" he declared, and was then felled by a heart attack. They burned his books anyway.

Tereska Torrès, then Tereska Szwarc, was not yet 20 when she joined Charles de Gaulle's Free French Forces in London in 1940. Her father, a member of the Polish Army in exile, fled Paris for Britain from the Atlantic port of La Rochelle.

While in London she met Georges Torrès (photo below left), who came from a family with connections on the left of French politics. His father Henry was a flamboyant Communist lawyer who later turned Gaullist, best known for defending anarchists and for mentoring the early career of French Socialist politician and lawyer Robert Badinter, who led the abolition of the death penalty when he was justice minister under President François Mitterrand.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

After the war, his mother Jeanne, known as Janot, remarried. Her new husband was an older cousin of Henry Torrès whom she had loved secretly since she was 15, a certain Léon Blum.

Henry Torrès married Suzanne Torrès, a war heroine who had left France in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's plane in 1940. She served with the French women's ambulance brigade Les Rochambelles and later married Jacques Massu, a celebrated French general.

Tereska Szwarc and George Torrès got married in May 1944, and she was pregnant when he was killed a few months later on the front in eastern France. Their daughter, Dominique, became an investigative journalist at public television station France 2 and is best known for a report exposing modern-day slavery.

Some of this early part of Tereska Torrès's life inspired a magnificent autobiographical book, ‘The Converts', published in New York in 1970 by Knopf (and in French as ‘Le Choix' by Desclée de Brower in 2002), in which she tells how her parents converted to Catholicism. After the war they would befriend a young priest called Jean-Marie Lustiger, a convert from a Polish-Jewish family who went on to become Archbishop of Paris under Pope John-Paul II.

The book also describes a scene in which Léon Blum, stepfather to her late husband whom she nicknamed Grappy, is overwhelmed at being asked to lead France for a third time. The first Jew to occupy such a position, he had headed the Popular Front government from 1936-37 and again in 1938.

"Grappy in tears. Janot standing up, her arms around him. Grappy, his head leaning on Janot's shoulder, repeating, his voice choked with emotion: 'I can't go on, Janot, I haven't got the strength any more, I'm too old.' Janot explained to me that the Party wanted Léon Blum to accept the post of President of the Council."(1)

-------------------------

1: Extract translated by Mediapart.

Soon after the war Tereska Torrès married a man 15 years older than herself, Meyer Levin, an American Jewish writer and film maker. He had taken part in liberating the Nazi death camps, and took her with him when he went to film camp survivors' journeys to Palestine, a project which led them to spend time in separate prisons in Haifa under the British Mandate.

They would live in Paris, New York and Jerusalem. Coincidentally, each of these cities is now home to one of her children. Her younger son, Mikael Levin, lives in New York and her elder son, Gabriel Levin, a poet who supports Palestinians expelled from their homes, lives in Jerusalem. She speaks proudly of one of her grandsons who got a taste of an Israeli jail for his activism.

It was Meyer Levin who encouraged Tereska Torrès to become a writer. Her first book, ‘Le Sable et l'Écume' (Sand and Foam), a novel begun in Trouville on the Normandy coast in September 1938 and completed in London in February 1945, was published by Gallimard in 1946. She signed the work as George Achard, using Georges Torrès's nom de guerre.

Then came her blockbuster, ‘Women's Barracks', in 1950. The extraordinary success this received among the lesbian movement was neither her intention nor happy surprise, and she had never wanted a French version of the book to appear. But, 61 years later, now close to her 91st birthday, she has finally completed a modified version.

‘Jeunes femmes en uniforme' is published by Phébus, price 22 euros.

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)