As the clock ticks down to France’s presidential elections due in April next year, centre-right President Emmanuel Macron has yet to announce his widely expected re-election bid, but his chances of winning a second term appear increasingly favourable as the divisions open up among his opponents.

While the Left is split between rival candidates, the principal conservative party, Les Républicains (LR), has yet to choose one out of a group of squabbling contenders, and now the far-right candidate, Marine Le Pen, who just earlier this year was eyeing a repeat of the 2017 elections (see the ‘Boîte noire’ box bottom of page), when she reached the second-round, two-horse play off against Macron, is facing a serious and growing challenge for her own electorate.

Enter, stage extreme-right, Éric Zemmour, a polemicist and political commentator who, after starting out on a career as a print journalist and becoming a regular columnist for French daily Le Figaro, has gained widespread notoriety since as a controversial political pundit on television shows, and more recently with the rightwing channel CNews.

Zemmour, 63, has not officially announced he is to run as a candidate, but few doubt that he will, as he travels France on thinly disguised campaign meetings, presented as conference debates around his recently published book La France n'a pas dit son dernier mot (literally, “France has not spoken its last word”). He is included in opinion polls of voting intentions, in which he is closing in on, and even in some leading, Le Pen. This remarkably rapid success is in no small part fuelled by the vast media coverage of the maverick’s rise to the electoral arena.

Zemmour, the son of Algerian parents of Jewish origin and who has several convictions for hate speech and inciting racial violence, is fervently anti-Islam, anti-immigration, anti-establishment and even, paradoxically, scathing of the media, to which he owes his prominence and which he claims is anti-France. His brazen comments contrast with the attempts over recent years of Le Pen, leader of the Rassemblement National (RN) party (the former Front National which she became leader of in 2011), to soften its racist image. He places himself as the unapologetic mouthpiece for the various components of the ultra-right (as well as for some among the mainstream Right), who have waited years for such a phenomenon.

While Le Pen and her party’s leadership have been cleaning up their political shop window over the past decade, ridding it of the most embarrassing hardliners, the bitterness felt by those swept under the carpet is returning like a boomerang to hurt it. A whole swathe of the ultra-right look upon Zemmour’s future candidature in the elections as a benediction, and an opportunity of reaching power.

Neo-Nazis, royalists, identitarians and Catholic fundamentalists have found in Zemmour a candidate who welcomes their support with open arms. Thanks to him and his vast presence across the media, the more marginal elements of the far-right, for long shut away in the wings of political debate, who complain of being demonised and who often describe themselves as ‘dissidents’, are hoping their hour has at last now arrived.

Speaking at a meeting in the north-east city of Lille earlier this month, and which was supposedly a conference to present his latest book, Zemmour told the assembled press: “Count on me to continue to say the same things. I don’t care about demonization, because it’s you, journalists, who manufacture it. If I am the demon, then there are seventy percent of the French who are demonic. I couldn’t care less about your right-minded thinking.”

A recent programme on the online video channel Livre noir (“Black book”), launched on YouTube to accompany Zemmour’s campaign by associates of Le Pen’s niece, the former far-right MP Marion Maréchal, gave an insight into what the polemicist’s supporters call the “union” of rightwing movements; a heteroclite mixture of all the radical factions excluded by, or no longer attracted to, Le Pen’s RN party, which they regard as having moved too far towards the mainstream, and having too much of a complex about its racist image.

With no party structure behind him, Zemmour can count on the rallying support of what has become called in France “the fachosphère” (for “fascist-sphere”), designating the loose collection of websites and social media accounts managed by those promoting far-right views and propaganda.

Many of these, including YouTube commentators Papacito, Julien Rochedy and Baptiste Marchais, joined a gathering on a barge anchored on the River Seine in central Paris on October 6th, together with Marion Maréchal and Thaïs d’Escufon, the former spokeswoman of the far-right Génération identitaire (GI) movement which in March this year was officially ordered by law to disband for reasons of its seditious activities and “xenophobic ideology”.

That evening, Papacito (real name Ugo Gil Jimenez), gave an interview to Livre noir in which he declared: “For me, Éric Zemmour is the panacea, it’s what will cure France.” Referring to his fanciful account of the history of France, from the 8th-century Duke and Prince of the Franks, Charles Martel, to the 11th-century French nobleman and leader of the First Crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon, and the 14th-century Breton knight Bertrand du Guesclin , Papacito, some of whose YouTube videos attract around a million views, added: “Those guys defended a thing: France […] It’s for that reason that I’m very receptive to what Éric Zemmour says, because I sense that he also has that same weight. I sense that he also has, in a different manner, inherited all this French tension, this thirst to be reborn, to rebecome dazzling.”

“I sense in him that project,” he continued, “and there are lots of people who sense that project in him […] This dynamic means that in 2022 we have an appointment with history. The French must not make a mistake. Éric Zemmour can be the vehicle for the return of France.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Beyond the admiration from figures like Papacito, who are popular with a young audience, Zemmour is also supported by the older, traditional figures of the national far-right. They include Renaud Camus, whose racist rhetoric about “the Great Replacement” has become a regular talking point in studio discussions on French rolling news channels.

Another is Jean-Yves Le Gallou. In commentary published on the far-right website Breizh-info, he declared. “By dint of diluting her ink with water, Marine Le Pen no longer makes a mark. The strategy of “de-demonising” has triply failed: Marine Le Pen has succeeded in demobilising her electorate without, for as much, reassuring opinion nor becoming credible. She has thrown out the ideas, thrown out [party] cadres, emptied the cashbox and now the urns. […] By being divisive, Zemmour mobilises (like Sarkozy had done in 2007) and reunites.”

In a post on Twitter in June this year, Le Gallou set out what he believed were the ingredients for a possible electoral victory for Zemmour, who he said occupies a “triple space”. These were: “The LR [conservative party electorate], flouted by their apparatus and the media, the identitarians despised and ignored by the Marine-ist [RN] apparatus, a lot of abstentionists dissatisfied with the political offer.”

Another figure of the “fachosphère” is Daniel Conversano, present on YouTube and who defines himself as an “ethno-differencialist” – a white supremacist. He has published the works of the late far-right theorist Guillaume Faye and had planned to do the same with the writings of negationist Robert Faurisson, who died before the project got under way. Conversano has also come out in support of Zemmour. “Éric Zemmour says what we in the national camp have been saying for years on the internet,” he said. “He ended up saying it on television […] When Z [Zemmour] talks, I am one-hundred percent behind him […] It’s wonderful. He’s dazzling.”

Conversano has said that he had voted for Marine Le Pen, but regarded what he considered her toned-down stance on Islam as a betrayal. For the ultra-right, where anti-Semitism prevails, Zemmour’s Jewish roots represent an obstacle to be surmounted. Conversano has said that the reason why he would vote for Zemmour and not for Marine Le Pen is “to win”.

“If one talks about race […] I’d prefer that Marine Le Pen had the talent of Éric Zemmour because Marine Le Pen is truly French,” he has declared. “[…] You know my ideas. You know what I think of the taboo subject with a capital R. I would prefer that Marine Le Pen was effective.”

“We have Zemmour who acknowledges the legacy of Pétain, who lunches with the daughter of Ribbentrop, it’s a wind of freedom,” said Conversano, referring to Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of the wartime collaborationist regime of Vichy in occupied France, and to Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi Germany’s foreign affairs minister, who was executed in 1946 after he was found guilty at the Nuremberg trials of helping bring about WWII and the Holocaust.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

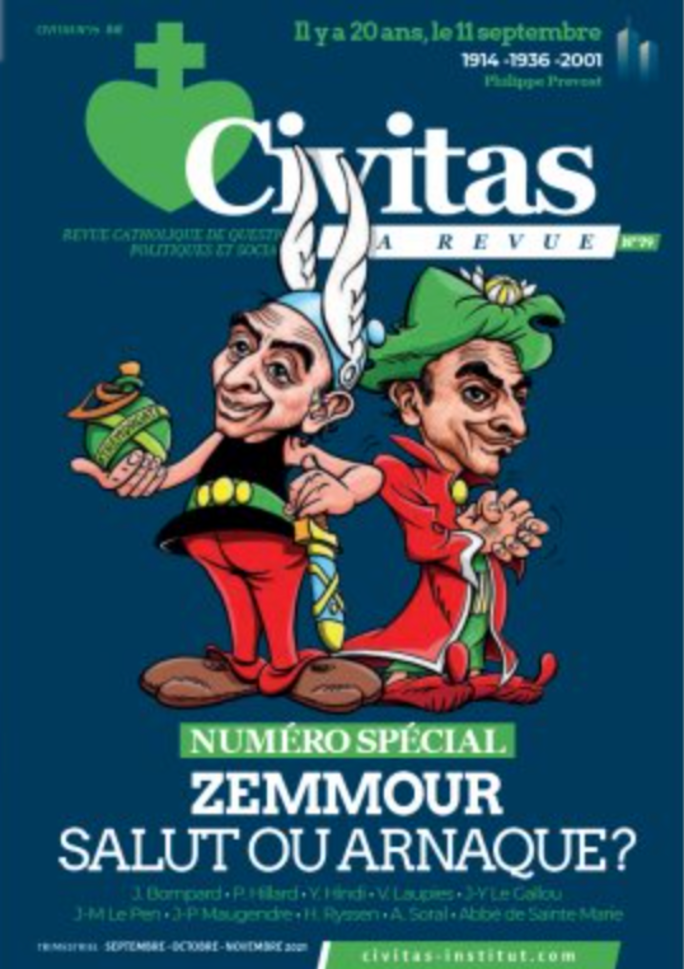

Hervé Ryssen, a far-right French essayist, convicted on several occasions for anti-Semitic comments, and who represents, alongside far-right ideologue Alain Soral, the most virulent of outspoken anti-Semitic militants among ultra-right movements, has also joined his support for Zemmour. After his latest conviction, in May this year, for anti-Semitic insults and “disputing a crime against humanity”, he wrote an article published in the Catholic fundamentalist review Civitas (see cover, right), entitled “Zemmour – salvation or fraud?” in which he gave a lengthy and convoluted explanation of, in substance, why he, an anti-Semite, could support a Jew.

“Now, there is a small handful of purists who will always consider Zemmour as an enemy because of his Sephardic Jewish origins, whatever he says and whatever he does,” wrote Ryssen. “I am well aware of the capacity of some members of the ‘chosen people’ to transform themselves into everything and anything in order to absorb a political opposition, to circumvent their adversaries and win over the most restive. […] But I also know that in history, numerous Jews have come out of Judaism; and some sincerely converted to Christianity. You might say to me that Zemmour has not converted! But it’s not by spitting on him that he will take the step towards us.”

Grégory Roose is a columnist for the French far-right weekly Valeurs actuelles, and the author of several essays about immigration and Islam. Roose, who was a local branch secretary of the then Front National (now renamed Le Rassemblement National) in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence region of south-east France, and who left Marine Le Pen’s party in 2018, recently published an essay entitled Journal d’un remplacé, à l’usage des esclaves des grands et petits remplacements (“Journal of a replaced, for the use of those slaves of great and small replacements”), in which he notably argues that “France has the right and the duty to retrieve its unity, its ethnic homogeneity”. Roose has also come out in support of Zemmour. In an article published on August 23rd in Valeurs actuelles, he wrote: “In 2022, Marine Le Pen could have two options: to either lose in disgrace or sacrifice herself for France”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Thomas Joly is the chairman of the Parti de la France, a micro-party ("micro-parti" in French, which are generally registered as associations, with a smaller organisational and financial structure than large political parties), which was founded in 2009 by Carl Lang, a former Front National Member of the European Parliament. Joly, who happily poses for photos wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with a homage to Marshal Pétain (photo left), came out in support of Zemmour as presidential candidate during a “grilled pig party” held earlier this year.

There is also Thomas Ferrier, leader of a racist group promoting identarian ideology, the Parti des Européens, who recently commented on Twitter that Marine Le Pen was “uninteresting”, and that, “She is going to suffer a memorable electoral hammering”.

“And we will all applaud,” he continued. “Zemmour designates and names the true peril. The whole of Europe must unite to face up to it. A united Europe is our fortress.” In his political policy programme, Ferrier argues for a European citizenship defined by origin and the “principle of patrilineal and matrilineal descent”. In a brochure written under a pseudonym, entitled Fascisme, fascismes, national-socialisme, he argues for the rehabilitation of such ideology “concerning its values, if that cannot be its name”. Ferrier has offered to run for Zemmour in legislative elections due to be held next June following the presidential poll.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version, with added reporting, by Graham Tearse