Nelson Mandela, figurehead of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, president of post-apartheid South Africa from 1994-1999, spent almost 28 years of his life in prison, between August 1962 and February 1990.

Those who imprisoned him for so long, so inhumanly, were the target of wonderful satire and ridicule by South African comedian Pieter-Dirk Uys, as shown in the video below. But today, watching that hilarious extracts, our tears are not of laughter, but those of grief.

Uys, revolted by the brutal repression of the Soweto Uprising in 1976, burst onto the South African scene and directed his immense comical power against the ruling Afrikaner Nationalist Party and its racist policies. Later, after the end of apartheid, his target became Mandela’s successor as president, Thabo Mbeki, and his obstinate, ostrich-like position on AIDS.

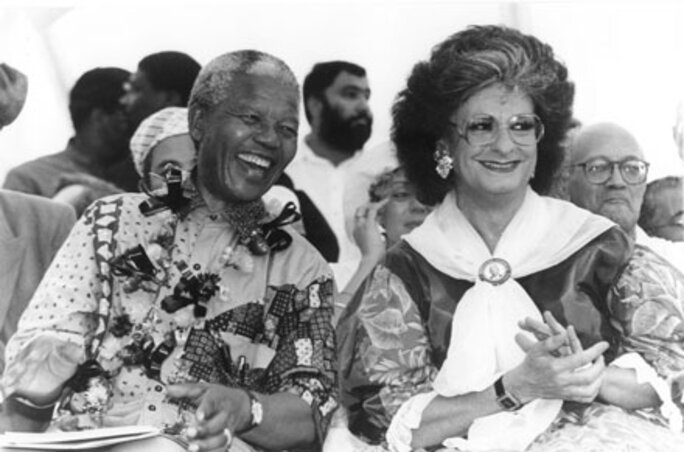

While Uys revelled in attacking all the taboos of South African society, he never targeted Mandela, protecting him like a close and fragile friend. He was, however, heard to gently tease Mandela, by then rather elderly, at Johannesburg’s Market Theatre, proclaiming: "We are all children of God!" with Mandela's distinctive accent and rolled 'r's. But Madiba, the tribal name by which Mandela is known, could only prompt affection, not sarcasm, even if the cult around him was sometimes excessive.

Uys made most impact when in the character of Evita Bezuidenhout, a progressive but eccentric Afrikaner activist who seemed to be inspired by the Dame Edna Everage character created by Australian humourist Barry Humphries in the 1960s. He cross-dressed and sported a bouffant wig in his pillory of the apartheid regime and expose its unpalatable truths.

Uys was just one of many Jewish opponents of apartheid to take up common cause with South African Blacks, Coloureds and Indians. They also included communist activist Joe Slovo (1926-1995), progressive politician Helen Suzman (1917-2009) and many more, and their presence in the anti-apartheid struggle ensured that the radicalisation of that struggle was not synonymous with its ‘racialisation’. Unfortunately, Mandela’s passing officialises the end of this common cause between Jews and Blacks (see Mediapart’s article on this theme).

Within the African National Congress (ANC), Mandela was the person most attuned to this question. His passing sounds the death knell for the ideals of the Rainbow Nation that succeeded the apartheid regime, at a time of heightened tension over next year’s parliamentary elections.

Amid today’s all-pervading globalisation that blurs the lines and makes it hard to identify struggles, in an era marked by an uncontrolled capitalism reminiscent of the Hydra that Hercules had to slay, the world has lost the perfection of Mandela’s clear commitment to boundless intransigence without extreme violence. Ideals that are also embodied by Vaclav Havel and Aung San Suu Kyi, reminiscent of a Jean Jaurès or Gandhi, only without the assassin’s bullet waiting for them.

Mandela managed to avoid the double-edged trap of white racists calling upon him to submit in the name of his belief in tolerance, and hotheads who were ready to die, right to the last remaining pacifist among them. He was able to defeat a hated object, apartheid’s so-called separate development, as well as hate itself. He was able to forgive the persecutor once persecution was no longer possible. He was able to give voice to the fraternity advocated by various religions and by the French Revolution.

His legacy is his personification of the Southern African philosophy of Ubuntu, a complex notion of ideal relations and exchanges within a community and between a community and outsiders involving warmth, cooperation and sharing, humanity and redemption. Mandela took his Ubutu into the political arena, an achievement recognised when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 together with the last representative of apartheid, Frederik de Klerk.

Mandela, born in Transkei in the eastern Cape in 1918, escaped the destiny that awaited him there by qualifying to go into further education. He escaped the marginalisation that could easily have followed after he and Oliver Tambo (1917-1993), a key figure in the ANC, along with several others were expelled from Fort Hare University in 1940 after a student strike. In 1951 he and Tambo became the first black lawyers in Johannesburg.

He spared South Africa a potential bloodbath, pushing the ANC, which he joined in 1944, to embark on a campaign of civil disobedience, then sabotage, then armed struggle, to defeat the apartheid regime set up by the ruling National Party in 1948. He managed to avoid succumbing to the paranoia of the underground leader when he was on the run – until his arrest and the subsequent Rivonia trial from 1963 to 1964.

He also escaped the death penalty sought by then justice minister John Vorster, who backed down in the face of worldwide protests. And finally, he avoided the personality disintegration that 27 years of captivity could so easily have brought about.

Once released, he sought to build, smile, absolve, love and try to bring harmony. It is always possible to criticise, to say he had an unfortunate complicity with former Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi or other African dictators, or a weakness towards those who spoke or acted in his name. He was certainly not a saint.

He was a reference, a beacon, a hero. For him, millions of people will sign a register, bring a flower, send a message or find some other way to pay their respects, something they would never do for any other world leader.

While Margaret Thatcher’s funeral in London in April had something odious about it, as if it were the final manifestation of the white race’s claim to supremacy, Mandela’s funeral will doubtless reflect his immense stature, his charm, his force and the subtlety of this outstanding human being whose death is like an amputation for each and every one of us.

Mediapart presents the video below in remembrance of Mandela and his magnetism. He came among us, disdained ingratitude, took pleasure in making changes and demanded improvements. Right at the end of the video, his dancing appears as if to transmit his message of hope.

- A documentary, in English, about Pieter-Dirk Uys can be found by clicking here.

-------------------------

English version by Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)