It is now nearly 25 years since the last genocide of the 20th century, committed against the Tutsis in Rwanda, took place. Close to a million people were killed in the space of a hundred bloody days in 1994. Yet there is still information about that genocide which remains hidden from public gaze.

A joint investigation by Mediapart and public service broadcaster Radio France has revealed the existence of several previously unknown documents that relate to two key aspects of the Rwandan tragedy. One is the assassination on April 6th 1994 of the Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana, which is considered to have been the spark which set off the first massacres. The other is the continued sale of arms to the genocidal regime in the country despite the presence of an international embargo.

In both cases France, which for a quarter of a century has been accused of compromising behaviour towards the extremist Hutu regime in Rwanda before, during and after the genocide, is once again in the front line of the debate.

1. Forgotten report by French intelligence agency DGSE

It was 8.21pm on April 6th 1994 and the pilot of the Falcon 50 jet that was carrying Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana and his Burundi counterpart Cyprien Ntaryamira informed the control tower at the airport at Kigali in Rwanda that he was preparing for landing. The Rwandan head of state was returning from Tanzania where, reluctantly, he had concluded a deal with the Tutsi rebels from the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), against the advice of the most radical Hutu group, who were supporters of the president.

At 8.25pm the plane's distress signal was activated but it was too late. Two missiles had just been launched and were hurtling through the Rwandan night. One hit the target and destroyed the aircraft. None of the nine people on board survived. In the following minutes widespread massacres of Tutsis began. The genocide that had long been planned by Hutu extremists now got underway in a grimly methodical manner.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

For nearly 25 years two opposing theories have been debated in public and the courts as to who was behind this assassination of the Rwandan president which triggered the genocide. One theory places the blame on the RPF, the other on Hutu extremists.

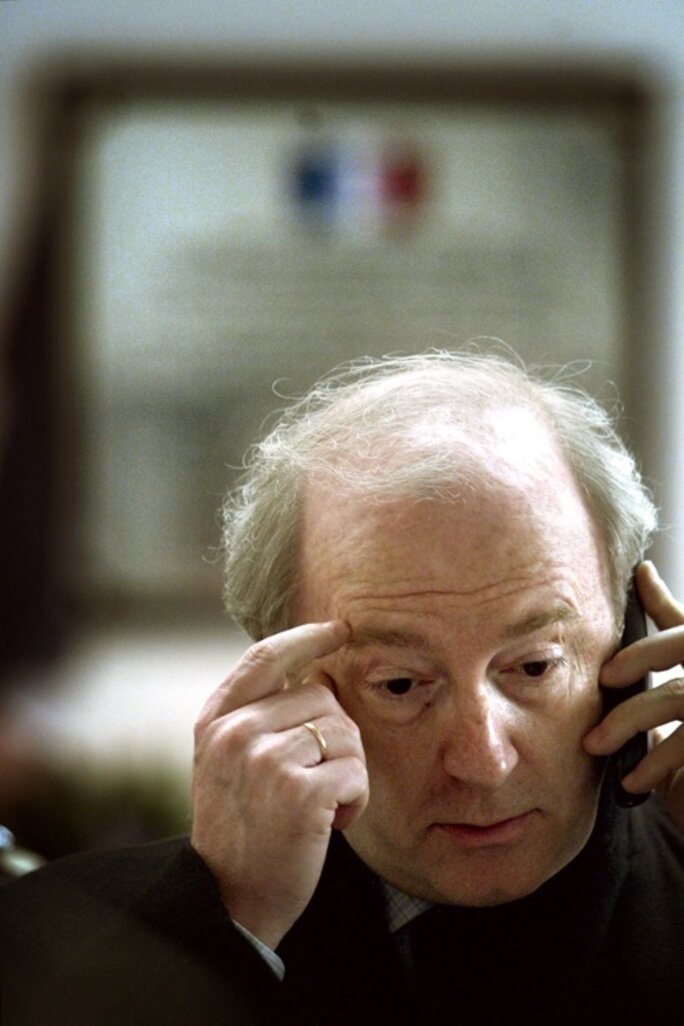

France, which at the time of the assassination was led by socialist president François Mitterrand in political 'cohabitation' with a right-wing government led by prime minister Édouard Balladur, has always favoured the first theory.

On April 7th 1994 President Mitterrand's advisor Bruno Delaye wrote in a “flagged” Élysée report: “The attack was attributed to the Rwandan Patriotic Front.” That same day, in another flagged report, General Christian Quesnot, the French president's personal military chief of staff, portrayed the theory of the RPF's involvement as a “plausible hypothesis”.

Some days later, on April 25th, France's ambassador in Kigali, Jean-Michel Marlaud, noted that the attack was “probably the work of the RPF” and he considered as “very weak” the notion that extremist Hutus had been behind it. “Without being proven, … the responsibility of the RPF is much more plausible,” he said.

On April 29th General Quesnot stated: “It's been said that the Hutus destroyed the aircraft. But that's wrong. It was mercenaries, recruited by the RPF or coming from them, who brought down the aircraft.” The senior officer's reading of events at the time was that the Tutsi RPF had been utterly cynical in bringing down the plane; they hoped that, having provoked massacres against their own people by assassinating the president, they would then be able to seize power after the resulting civil war.

“The Presidential Guard, whose head was killed with the president, and which was not made up of choirboys, began to start massacring: their president had been killed. That was exactly what the RPF wanted because President Habyarimana constituted the only real obstacle to it taking power,” was the analysis of General Quesnot. He readily spoke of the Tutsis as “Khmers Noirs” - a reference to the Khmer Rouge – under the influence of the “Anglo Saxons” who wanted to use them to reduce France's power in this part of Africa, known as the African Great Lakes region.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

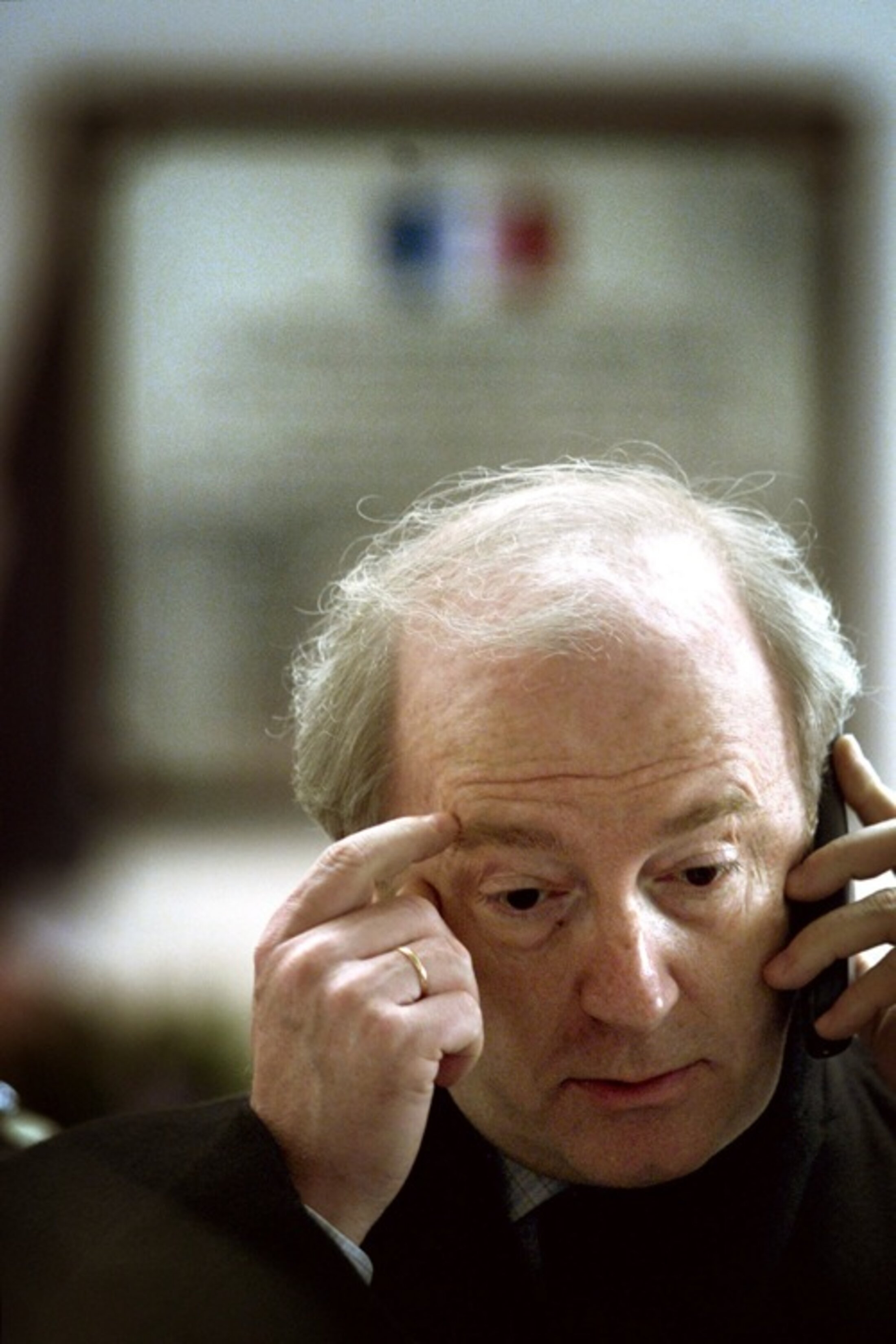

Despite the passage of time, François Mitterrand's supporters have not changed their minds as to who carried out the assassination. In February 2017 Hubert Védrine, who at the time was Mitterrand's right-hand man in charge of the Élysée, said of the April 6th 1994 killing in the Le 1 weekly publication: “In 1995 we knew nothing about it. Over the years my conviction has grown that it was probably Kagame [editor's note, Paul Kagame who led the RPF at the time and is now the country's president].”

But is it really true, as Védrine says, that the French state's military and intelligence services knew “nothing” at the time? Mediapart and Radio France's investigation unit have found a report from France's overseas intelligence agency the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure or DGSE which has never been revealed before now, and which from as early as September 22nd 1994 portrayed Hutu responsibility for the assassination as the “most plausible hypothesis”.

This was exactly the opposite of the theory that was being defended at the time by the Élysée, whose blinkered policies led France into a series of compromising situations in relation to the genocidal regime in Rwanda.

This “confidential” defence report was declassified by the Ministry of Defence on September 17th 2015 as part of the investigation into events in Rwanda carried out by Paris-based investigating judges Marc Trévidic and Nathalie Poux.

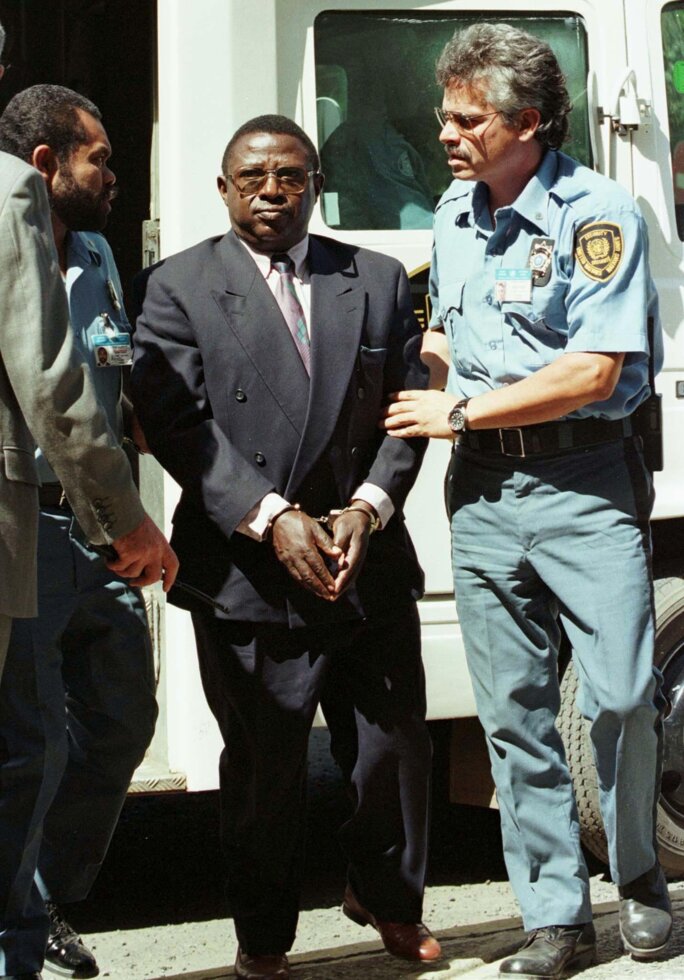

This French intelligence service document referred to two regime extremists, Colonels Théoneste Bagosora, former chief of staff to the minister of defence, and Laurent Serubuga, former chief of staff at the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR), as the “principal figures behind the attack of April 6th 1994”.

The French agents go back over the background of Colonel Bagosora, considered to be one of the “brains” behind the genocide against the Tutsis – he was given a life sentence reduced to 35 years on appeal by the International Criminal Court – and of Laurent Serubuga, seen as another key player in the massacres, and who came to France in the 1990s.

“Both natives of Karago, like the late president Habyarimana, [Théoneste Bagosora and Laurent Serubuga] were for a long time considered to be the legitimate heirs to the regime,” wrote the DGSE. “Their retirement, announced in 1992 by President Habyarimana, when they were hoping to obtain the rank of general, with the relating privileges, was the origins of a deep resentment and of a noted rapprochement with Mrs Agathe Habyarimana, the president's widow and often considered to be one of the main brains behind the regime's radical tendency.”

The report continued: “This operation [the attack on President Habyarimana's aircraft] had apparently been premeditated for a long time by the extremist Hutus. The murder of ministers from the moderate opposition and of Tutsis, less than half an hour after the explosion of the presidential Falcon, would confirm the high degree of planning in this operation.”

For the French soldier Guillaume Ancel, who has been campaigning for France to accept some responsibility for the genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda, this unpublished DGSE report is crucial. “This report,” he says “is the proof of French denial in this story. Thanks to the DGSE we knew everything from the start and yet the top political echelons of the state constructed some alternative facts.” He continued: “We knew that the massacres were being prepared, and we supported the future committers of genocide; they committed atrocities and we supported them; and after the genocide we continued to support them. France is complicit.”

It was, moreover, not the first time that the DGSE had alerted the highest echelons of the state in this way. From February 13th 1993 French intelligence agents had spoken, in a report, about plans for a “vast programme of ethnic cleansing directed against the Tutsis, of which the creators were apparently people close to the head of state”.

On April 8th 1994, two days after the attack on President Habyarimana's aircraft, the overseas intelligence agency wrote that “the current events have to be put in a context of confrontation between Hutus from the North and Hutus from the South” with the “possibility of an organised and carefully prepared political plot, as shown by the carrying out of the attack, which is relatively complex on a technical level.”

Three days later, on April 11th 1994, the DGSE thought that the missiles that destroyed the presidential plane came from the “edge of the Kanombe military camp” at Kigali which was controlled by the presidential guard. From the start French agents seem to have rejected the idea that the Tutsi RPF were responsible for the attack.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The analysis carried out by judges Trévidic and Poux confirmed in 2012 that the “most likely” location where the missiles were fired from was the “Kanombe site”, where the presidential guard was based. The official investigation in France ended in December 2018 with no charges being brought. This meant that nine members of the RPF who had been placed under formal investigation as part of that probe faced no charges.

The content of the French intelligence reports is also confirmed by notes written by Belgian intelligence agents. On April 7th 1994 the Belgian intelligence service the Service Général du Renseignement Belge (SGRS) said it considered that those who fired the missiles at the aircraft “are not necessarily the RPF … but could well have been soldiers who don't want peace”.

On April 12th the SRGS wrote that “in Rwanda everyone thinks that it's Colonel Bagosora who is responsible for the attack on the presidential plane”. This was confirmed by one of the service's informers who, in a report dated April 15th, claimed that it was “Colonel Bagosora who is behind the attack on the presidential plane”.

The theory that it was Hutu extremists who carried out the assassination was also supported at the time by the former director of Rwanda's central bank Jean Birara. On May 26th 1994 Birara told Belgian military investigators how the extremist Hutus grouped around Colonel Bagosora had started, he said, a “plot” against President Habyarimana who “seemed to have decided, this time, to apply the Arusha accords”. This was a reference to the political negotiations which led to power sharing with the RPF.

According to Jean Birara it was Colonel Bagosora who “took the decision to destroy the president's aircraft”, in agreement with the family of President Habyarimana's wife.

The analysis was the same in the United States, where the administration at the time backed Paul Kagame. According to a declassified document dated April 7th 1994 from the Bureau of Intelligence and Research Share – an intelligence agency at the US State Department – that Mediapart and Radio France have seen, a source, whose identity has not been made public, “indicated to the ambassador David Rawson that some extremist Hutu soldiers (who could belong to the presidential guard) are responsible for the attack on the plane which was carrying the Rwandan president Habyarimana....”

In a declassified memo dated April 8th 1994 and addressed to the American defence secretary, this phrase can once again be found: “Extremist Hutus probably destroyed the president's plane.” Behind these extremists was the figure of Théoneste Bagosora.

When contacted, the lawyer representing Agathe Habyarimana, who according to the September 1994 report by France's DGSE was suspected of being closely linked with the plot which would end with her own husband's death, rubbished the accusations. Lawyer Philippe Meilhac spoke of a report whose “content was anachronistic” and noted that other documents from the same intelligence agency were more nuanced as to the responsibility for the attack on April 6th.

The lawyer, who backs the idea that the RPF were responsible, also pointed out that his client had the status of a civil party – in other words a victim – during the investigation into the murder of her husband and that she had never been placed under investigation in proceedings as to her potential political responsibility in the genocide.

When Hubert Védrine was asked about the Mediapart and Radio France revelations concerning the DGSE report he said that it was “quite possible”. “There was a pile of reports, of various origins, envisaging the two hypotheses ...The two interpretations, extremist Tutsis or Hutus, are in any case honourable for France as the people who acted did so to halt France's compromise with the Arusha Accords [editor's note, signed by President Habyarimana],” said the former secretary general of the Élysée at the time, who is considered by many journalists and historians who specialise in Rwandan affairs to have been one of those responsible for France's compromising role in the tragedy.

2 The BNP bank and weapons for those behind the genocide

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The name of Colonel Bagosora, who is sometimes nicknamed “Rwanda's Himmler”, also appears in the investigation opened in France in September 2017 against the bank BNP Paribas for “complicity in genocide and complicity in crimes against humanity” following a complaint lodged by the associations Sherpa, the Collectif des Parties Civiles pour le Rwanda and Ibuka France. The investigation is being carried out by the French judges Alexandre Baillon and Stéphanie Tacheau.

The bank is suspected of having contributed to the funding of an illegal purchase of arms destined for Rwanda in June 1994, two months after the genocide started. This was despite an arms embargo voted by the United Nations a month earlier. Eighty tonnes of weapons are said to have been delivered from the Seychelles to Goma in Zaire (now called the Democratic Republic of the Congo) close to the Rwandan border.

At the International Criminal Court on November 10th 2005 Théoneste Bagosora acknowledged that this arms delivery took place, which came from the Seychelles in two flights.

Judge Baillon tried to question the former “brains” behind the genocide, who is currently in custody in Mali. But on February 14th 2018 the Malian authorities gave their response to the French judge: “Théoneste Bagosora has indicated that he does not want to discuss this case with us, nor to be heard by the French judge, and that he would not reply to their questions.”

But the flow of finance tells its own story. To help him buy the arms in the middle of an embargo Colonel Bagosora enlisted the services of a South African intermediary, Petrus Willem Ehlers. The former private secretary to P.W. Botha, the South African prime minister then president in the apartheid era, Ehlers played a key role in the delivery of illegal arms thanks to a Swiss bank account opened on October 14th 1993.

The 'letter rogatory' or letter of request sent by the French judges to the Swiss authorities who had investigated this issue in the 1990s formally established that Petrus Willem Ehlers had indeed used his account, called CHEATA, at the Union Bancaire Privée (UBP) at Lugano in Switzerland to receive the money relating to this arms sales.

The documentation supplied by UBP for June 14th 1994 shows that the South African middleman's account was credited with 592,784 dollars from an account at the National Bank of Rwanda.

Two days later, on June 16th 1994, the same account was credited with 734,099 dollars. This money was afterwards transferred from an account at the Central Bank of Seychelles to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on June 15th and 17th 1994. Documents supplied by UBP in Lugano to the Swiss authorities also show that the Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP) had indeed authorised these two payments, which is the basis for the French judicial investigation.

The BNP declined to comment.

In a letter sent to his head of legal affairs on October 8th 1996, the person who managed arms broker Petrus Willem Ehlers' bank account wrote: “We could see that it concerned an 'African style' commercial transaction. [The] CHEATA [account] operated as an intermediary in a sale of prefabricated huts between South Africa and Zaire on one side and the purchase of fresh fish between the Seychelles and Zaire.”

In fact, the deal had nothing to do with “fresh fish” but concerned arms. When the person in charge of Petrus Willem Ehlers' account was questioned by Swiss police on December 4th 1996, he said he was completely unaware of the real nature of the merchandise involved behind the flow of money.

“In 1994, during my business relations with Mr Ehlers, I never had the slightest suspicion that it could in fact involve arms trafficking. The supplies of fish could potentially have masked this arms dealing,” said the bank official concerned, Adrian S.

In a bid to shed more light on the context to these arms sales and to evaluate what BNP knew about the risks of such a financial transaction at the time, the French judges also questioned Jacques Simal. This former head of the Banque Bruxelles Lambert (BBL) had been seconded to the Banque Commerciale du Rwanda (BCR) until April 1994, before returning to Belgium to head the bank's “crisis cell” over its dealings with Rwanda.

His evidence is decisive. Jacques Simal described how the Hutu extremists used every means to get their hands on some extra money after the start of the genocide, in particular through the governor of Rwanda's national bank. This was the same bank that was used in June 1994 to buy 80 tonnes of weapons that were delivered from the Seychelles.

“The governor [of the national Bank of Rwanda] was someone who was very involved politically with the government, I'm thinking of the Hutu Power section [editor's note, extremist Hutus], these are some things I was told at the time,” Jacques Simal told the judge Alexandre Baillon, during a trip by the latter to Belgium, on February 6th 2018.

“He was behind attempts to draw funds from the BCR [editor's note, Banque Commerciale du Rwanda] in favour of the national bank. He had demanded that all the private bank funds were repatriated to the BNR [national bank] as in fact the interim government [editor's note, supporters of those carrying out the genocide] effectively considered the BNR to be its financial arm. The BNR considered that the cash held by the private banks belonged to it. For my part, I opposed these attempts at withdrawals, from the moment I was working on it in Brussels.”

The arms embargo adopted by the United Nations in May 1994 simply reinforced the Belgian bank's tough approach. “From the moment that there was this embargo, there was a meeting at Belgian MAE level [editor's note, Ministry of Foreign Affairs] to notify them of the circumstances of the application of this embargo,” said Jacques Simal during his evidence. “When the secretary general returned from the meeting he gave us the directives that no suspect transfer of funds at the request of Rwanda should be carried out.”

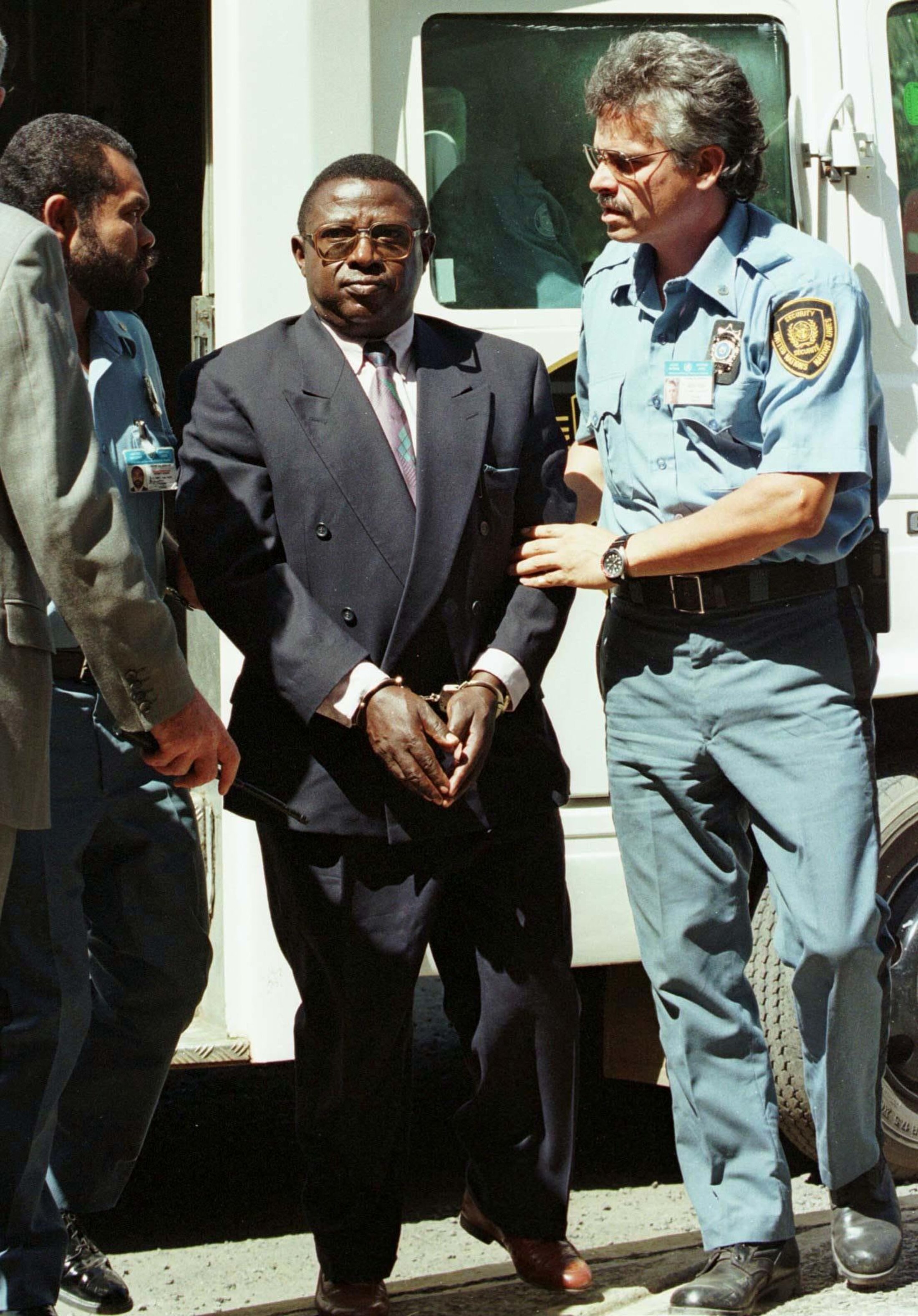

Questioned on January 28th 2019 by Radio France's investigations unit and Mediapart about these weapons deliveries, the former head of France's military chief of staff from April 1991 to September 1995, Admiral Jacques Lanxade said he had “never” had any knowledge of them.

“It's an issue which never came up for discussion at the [defence] committee [at the Élysée],” said Jacques Lanxade. “For a very simple reason: the supply of arms was forbidden by the embargo decreed by the United Nations. Speaking as the chief of the French military staff, which I was, nothing happened, in any case not under my authority. The supply of weapons can take place via several channels. The supply of weapons recognised by France was via the channel of the Ministry of Cooperation [editor's note, a ministry which worked with France's former colonies and which was closed in 1999] at the time, which was not under the authority of either the Ministry of the Defence or the head of the military chief of staff.”

On the question as to how the French military, who controlled the airport at Goma in what was Zaire, on the border with Rwanda, could have allowed 80 tonnes of weapons to pass in June 1994 in the middle of a UN embargo, Admiral Lanxade replied: “We only controlled a part of this air space, for our own needs, which were military needs. We didn't 'go after' the Zaireans in this area. It was up to them to do what they wanted, in the framework of the authorisations that they had. In any case, there wasn't a flow of weapons that crossed via Goma airport.”

Does this mean that 80 tonnes of weapons left from Goma in June 1994 and that the French army saw nothing? “That doesn't seem impossible to me,” said the admiral. “There is absolutely no evidence of it, perhaps some weapons did pass, I don't know. I can't answer you on that. But I can tell you that the French armed forces had nothing to do with that.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.