A worldwide treasure hunt is on to track down the still-hidden and massive fortune of late Libyan dictator Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and his clan, bringing together a disparate group of mercenaries, who range from weathered former US intelligence operatives to be-suited business lawyers.

Hired by the new authorities in Libya, where the missing funds are direly needed for the country’s reconstruction, the bounty hunters are rivals who can hope for big gains through commissions calculated against the sums recovered. According to different estimations, the total value of the Gaddafi clan’s stash worldwide is between 80 billion euros and 151 billion euros, much of it hidden away in tax havens behind shell corporations and aliases.

“When you have 100 million euros to recover, there’s already some nervousness,” commented Joël Sollier, director of legal affairs for Interpol, the international police cooperation agency. “When you have 1 billion, people are ready to kill. Here, we’re dealing with dozens of billions.”

Under the legal umbrella of the United Nations, the authorities in Tripoli are engaging the bounty hunters to localize the assets spoliated by the Gaddafi clan over several decades so that they can be frozen by local authorities and transferred back into the hands of the Libyan state. But the task is far from easy, fraught not least by the continuing complicity of a number of countries in protecting the remaining fugitives of the Gaddafi regime.

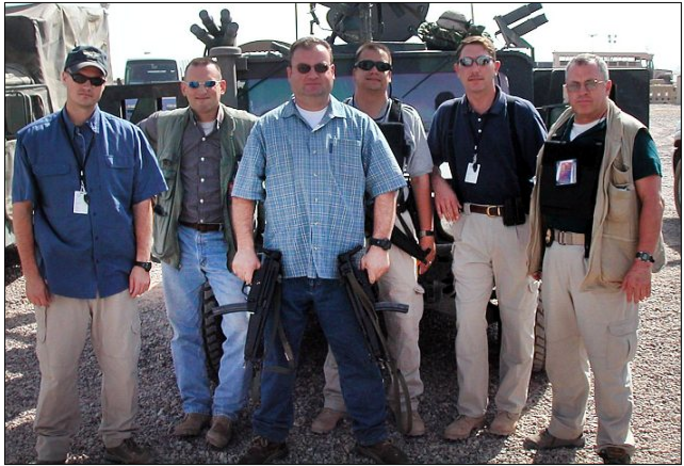

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Beyond the Gaddafi clan’s personal fortune, including artworks, jewels and bank accounts, a significant amount of the missing assets come from the former regime’s sovereign wealth fund and holding company, the Libyan Investment Authority, an opaque body with subsidiary units set up across the African continent.

The authorities in Tripoli suspect the fund is being used to finance former Gaddafi aides who are still on the run, and who include Bashir Saleh, 66, who headed the Libyan African Portfolio fund and who is the subject of an Interpol ‘Red Notice’ (also known as an 'international wanted persons notice') for his arrest on fraud charges. Tripoli is also concerned to block the stolen funds from being used to mount a future coup attempt.

The hunt for the missing billions began amid the chaotic political situation in Libya following the death of Gaddafi in October 2011, when the newly-formed National Transitional Council was weakened by internal rivalries and dissension. Contracts to trace the missing funds were handed out by the different, bickering parties acting separately and in some cases promising extravagant commissions of up to 15% of the value of the sums brought back to Libya.

Eric Vernier, a researcher with the French Institute of International and Strategic Relations, IRIS, and a specialist on the issue of recovering national assets used for personal gain by members of corrupt regimes, warned that the situation runs the probable risk of corruption in the form of ‘retro-commissions’,whereby the bounty hunter pays back part of his commission to the person who hired him. “Members of the government can impose their conditions on private companies: ‘We’re choosing you but you must think of us when you cash in your commissions,’” he said.

According to several media reports, including by the Lebanese daily, The Daily Star , the companies engaged in the bounty hunt include the Cohen Group, self-described as offering “global business consulting services”, a firm founded by former US Republican Senator William Cohen who served as Secretary of Defense under President Bill Clinton. Also cited is DLA Piper, an Anglo-American business law firm that has US politician Michael Castle, a former Republican Governor of Delaware and Member of Congress, as one of its partners and another US company, the Washington-based Eren Law Firm, to which former US career diplomat Victor D. Comras serves as a special counsel.

“The big companies subsequently employ sub-contractors and agencies in countries where they suspect the assets to be,” said Eric Vernier. “Some of these agencies get up to anything and everything to gain a lead, [including] the theft of documents and data, receiving stolen items, corruption and so on. The international firms delegate so as not to be responsible in the case of something going too far, even a killing.”

In some cases, the rivalry between local bounty hunters has caused embarrassment to the Libyans, such as in South Africa (where the government recently announced it was returning assets controlled by the Gaddafi clan, including banks and a chain of luxury hotels, to Libyan national ownership). Two groups of investigators in the country, one of which is linked to high-profile arms dealer Johan Erasmus, hunting a suspected $1 billion hidden in local banks, have become engaged in a slanging match over who is truly mandated by Tripoli, and mutually accusing each other of forgery of documents.

In a move in June 2012 designed to put some order in the mass of contracts that have been signed, the authorities in Libya created a single, centralizing agency called the ‘Committee for the recovery of assets’, headed by the director of the justice ministry’s litigation department, Bechir Ali Al Akari. In an interview this month with the French-language magazine on African affairs, Jeune Afrique, Al Akari explained that despite his efforts to reign in the cowboy elements among the bounty hunters, “some [private] services are still acting in an illegal manner thanks to mandates that were [previously] handed to them” and which, he said, “can only parasite our work and damage our credibility”.

Meanwhile, the political instability in Libya is a recurrent problem for those hoping to join the hunt for the missing fortune. “Ministers meet you very kindly, but you don’t know if they will still be minister the following day,” commented one French lawyer, speaking on condition of anonymity, who travelled to Tripoli earlier this year in the hope of gaining a contract

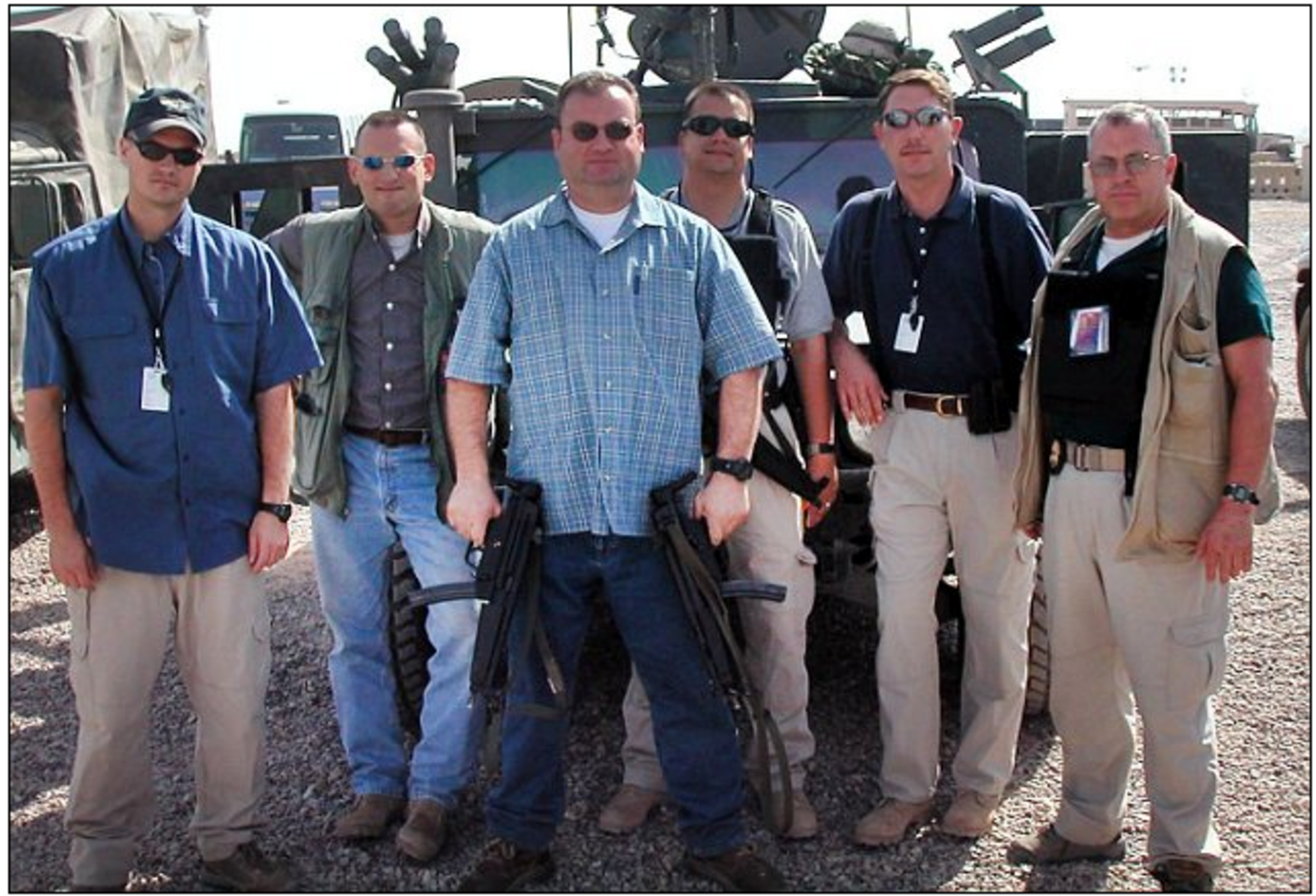

Enlargement : Illustration 2

One of the larger firms engaged by BechirAli Al Akari is a US company called Command Global Services (CGS). Juan Zarate, a former Deputy National Security Advisor on combating terrorism under the George W. Bush administration is a key figure in the CGS operation, for which a special team was set up under the field management of Charles Seidel, a retired CIA officer who served in Iraq and as the agency’s station chief in Jordan . Seidel was seen visiting Paris in June accompanied by Haig Melkessetian, described by the website Intelligence Online, specialized in reporting the intelligence world, as a former US Air Force intelligence officer.

Contacted by Mediapart, Juan Zarate declined to answer questions about the fees paid to CGS for recovering the hidden Gaddafi assets. “Command Global Services has been contracted with the Libyan government since May 2012, to assist in finding, freezing, and returning stolen Libyan assets – those controlled by the Qaddafi family and former regime, Zarate replied in an email correspondence with Mediapart. “We have created a world-class team of investigators, forensic accountants, financial analysts, lawyers, and other team members to execute on this mission credibly, strategically, and on a global basis […] We are finding success and are hopeful that our efforts will enable the Libyan people to access and leverage assets that were once pilfered by the Qaddafi regime.”

“We will not comment on the details of our confidential contract with the Libyan government or the details of our ongoing work," he concluded.

While it is impossible to establish the value of the assets recovered and returned to Libya over the past year, the rumoured sum of up to $10 billion is still well below the target.

In February 2011, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution calling on member states to “freeze without delay all funds, other financial assets and economic resources which are on their territories, which are owned or controlled, directly or indirectly” by Gaddafi, his wife and children (see full text here).

Under that UN resolution, member states are required to ensure that their nationals (individual persons but also banks and institutions) bar all access to assets held by the Gaddafi clan. A UN committee of five international experts was set up to assist in the freezing of assets by member states.

The UN has previously been involved in similar moves against former leaders of Somalia, Liberia, Ivory Coast and also al-Qaeda, the results of which have been far from convincing. “The biggest difficulty is detection,” commented Eric Vernier. Indeed, there is little chance that authorities in tax havens, or Qatari or Luxembourg banks, are likely to spontaneously announce they are holding the incriminated assets. While financial institutions in France are required, since a law passed in 2009, to declare those accounts they suspect are used for money laundering, “not everyone plays the game” according to Vernier. “It’s like with insurers who have insurance contracts that are unclaimed,” he said. “As long as the person doesn’t come along to ask for the money they keep the billions under their elbows.”

Once the ‘bounty hunters’ do trace the sums, the next problem is to obtain a freezing of the accounts or property, either through a unilateral decision by the local authorities or through a legal procedure launched by the state that was looted. In every case, proof must be provided of the illicit transit of the funds, which is often a tortuous legal process (and a profitable one for all those hired along the way). Even then, the recovery of the assets is uncertain if the local authorities express doubts about the probity or stability of the state applying for their return.

In a report published in February 2013, the UN Panel of experts on Libya detailed a disturbing first account of the moves to freeze Gaddafi’s hidden fortune. While a large number of countries had imposed, beginning early 2011, the freezing of a number of Libyan state funds (which were subsequently released after their control was returned to the new Libyan authorities), very few private assets were targeted.

Among the exceptions was the recovery of 80 million euros in Switzerland, and a house in London with an estimated value of £8 million which officially belonged to a maritime company based in the British Virgin Islands but which the British authorities established was in reality a front for one of Gaddafi’s sons.

“Substantial information has been gathered regarding efforts by certain designated individuals to negate the effects of the asset freeze measures by the use of front companies and through accomplices in various Member States who have been assisting them to that end,” the Panel reported. It highlighted the case of Gaddafi’s brother-in-law and notorious former intelligence chief, Abdullah Senussi, who was extradited to Libya from Mauritania last September, and who had access to an account held in a non-cited UN member state which had failed to notify and freeze it.

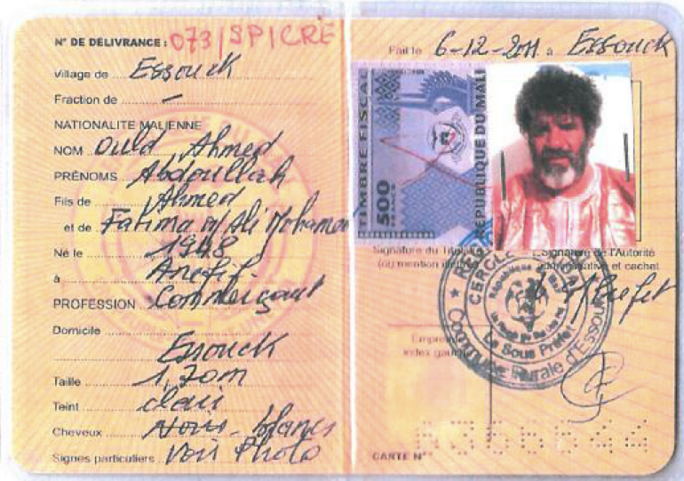

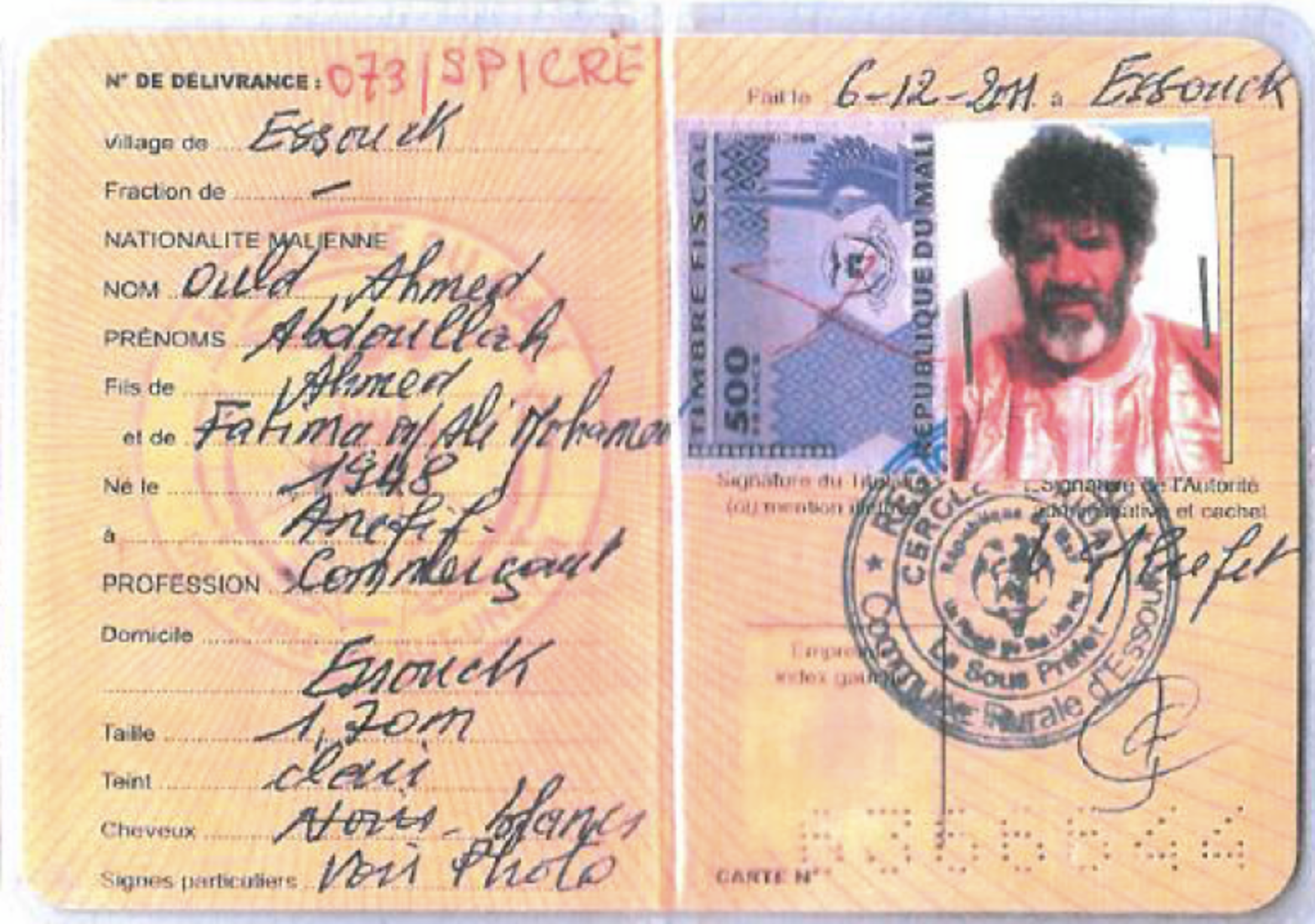

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Before his arrest in Mauritania, Senussi had been living in Morocco, where he received medical treatment in several private clinics. The Panel reported that it had “made further enquiry of Morocco to establish how Abdullah Al-Senussi had paid for treatment at the aforementioned clinics and to ascertain whether any bank accounts had been opened in Morocco in the name of the false identity, Abdoullah Ould Ahmed, wherein assets may be located that should be frozen under the asset freeze measures.”

The Panel contacted the Moroccan authorities with a request to carry out further enquiries on the ground in Morocco. “Although a reminder letter was sent, no reply has been received to that particular request,” it said.

Meanwhile, the Panel found that Colonel Gaddafi’s third son, Saadi Gaddafi, who was both head of the Libyan football federation and commander of the former regime’s special forces, and who is currently living in Niger despite an appeal by Interpol for his arrest, benefitted from “an extensive network of companies, bank accounts and facilitators has been identified across a number of Member States.”

“This network,” it reported, “has provided Saadi Qadhafi [1] with access to funds in contravention of the resolutions and involved a number of persons and companies in violation of those resolutions.”

The Panel found that the Chadian authorities were in clear violation of the February 2011UN resolution. It reported that “though they [the Chadian authorities] were aware of assets owned by the previous Libyan regime, the authorities have taken no measures to freeze them […] it was clear that the Chadian authorities were aware that the Qaddafi regime owned the Hotel Kempinski, through the Libyan Arab Foreign Investment Company, and the Banque Commerciale du Chari, which is 50 per cent owned by the Libyan Foreign Bank (now delisted, but previously listed under the terms of the original asset freeze measures). ”

A report in 2009 by French NGO CCFD-Terre solidaire, which contained a study of information available on the recovery of national assets looted by several dozen despots, including the Marcos family from the Philippines, Haiti’s former dictator Baby Doc and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, found that in all, just $4.4 billion dollars had been recovered by national governments while another $2.7 billion remained frozen. “Less than 5% of stolen assets were recovered,” the association concluded, underlining that most of these were handed back by the US and Switzerland.

Meanwhile, Eric Vernier suggested that the absence of an organised, vigorous international system to trace and recover spoliated national assets is not only good news only for dictators, but for the bounty hunters too. “In any case, it allows for the justification of lots of emoluments, fees, commissions,” he said.

-------------------------

1: The spelling in English of the name Gaddafi, variously given by the UN as Qadhafi and by others as Gadhafi, is a phonetic interpretation - in French it is normally given as Kadhafi - upon which few can agree a common rule. Mediapart English has chosen what is the usual spelling in British English, that of Gaddafi.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse