“Lots of people are becoming mystical, we don't trust the outside world and at the same we're afraid of being cut off from that world, and the craziest information is doing the rounds,” said Yasmine Payet, a resident on La Réunion, a French overseas département or county. Contacted by phone at her home, she describes the oppressive mood on the Indian Ocean island. “This morning someone gave me a learned explanation of how the virus can be transmitted by telephone. And there aren't yet any deaths. What will it be like when there are?” she wondered. The fear of contamination – in all senses - is a widespread one on Le Réunion.

By Wednesday April 1st 281 cases had been recorded on the island. The virus has been quickly transmitted and rapidly spread in a densely-populated land of 850,000 people. Around 20 or so new cases are recorded each day. And as in mainland France, 5,700 miles away, the economic life and social fabric of the island have been rocked by the strict lockdown that has been in force for two weeks.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In the French Caribbean, meanwhile, the grim counting of bodies has already started. A total of nine people have so far died on the French territories of Martinique, Guadalupe, Saint-Martin and French Guiana, and the number of cases has reached more than 275. More worryingly still, around 150 people are in intensive care in these overseas départements, which has stretched their hospital capacity to the limits in each case.

While hospital services and staff have been sorely tested by the virus outbreak in mainland France, the situation in the country's overseas territories has been catastrophic for a long time. It was in fact the poor state of the hospital in the French Guiana capital of Cayenne which was partly behind the major social protest movement in that region in 2017. And the Mamoudzou hospital centre on the Indian Ocean département of Mayotte regularly features in news stories by both local and national media because of its overcrowding and terrible sanitary conditions.

“You have to bear in mind though that our university hospital burnt down in 2017,” said Patricia Braflan Trobo from Guadalupe, an essayist who also has a doctorate in social sciences. “At the moment it's working just about ok but this hospital is a shame on France.” she said. “French health policy is viewed by those in the overseas territories as one of contempt. People take it very badly, seeing it as something insulting, a form of violence.”

And that is the perception in 'normal' times. All of this helps explain an event of major legal and moral significance which took place recently at Pointe-à-Pitre in Guadalupe. The UGTG trade union sought and won an injunction against the regional health authority or ARS, with the administrative court ordering this body to “order 200,000 Covid-19 testing kits from the companies SA Novacyt or Alltest Biotech, via the reseller Sobiotech Consult, which corresponds to half of the Guadalupe population” and also to “order the necessary doses to treat 20,000 patients for the Covid-19 epidemic with [anti-malaria drug] hydroxychloroquine and [antibiotic] azithromycin, as defined by the Mediterranean infectious diseases unit [run by Professor Didier Raoult in Marseille].”

In the injunction, which Mediapart has seen, the court justifies its decision by the “emergency situation … taking into account the constant worsening of the health situation in the country and in particular in Guadalupe, due to the very rapid propagation of the Covid-19 virus.”

The court ruling also describes the critical posture adopted by trade union leaders such as Élie Domota, leader of the Liyannaj Kont Pwofitasyon or LKP ('Movement against exploitation') - the group which spearheaded a general strike on the island in 2009 - as “legitimate”. A similar stance has been adopted in the Indian Ocean by Younous Omarjee, the European Member of Parliament for France's La France Insoumise ('Unbowed France') party, who represents La Réunion. The MEP Tweeted his anger that the health authority for France's Indian Ocean territories had stated that the French helicopter carrier Mistral, which has been despatched to support the overseas territories, was not intended to have “medical teams or medical equipment on board”.

“Idiots that we are, we thought that the Mistral helicopter carrier was coming to the Indian Ocean with medical support for the people of Mayotte and La Réunion,” Younous Omarjee Tweeted. “It is going to be used to transport equipment and repatriate French people who are abroad. Great for them, not so good for us. It was really worth all this fanfare around the helicopter carrier...”

On pensait le porte hélicoptère Mistral venir dans l’Ocean Indien en soutien medical aux populations à Mayotte et à la Réunion. Idiots que nous sommes. Il va servir à acheminer du matériel et rapatrier les francais se trouvant à l’etranger. »Tant mieux pour eux.Tant pis pour nous pic.twitter.com/fv2CTLsDuf

— younous omarjee (@younousomarjee) March 27, 2020

It is indeed the case that the sending of two helicopter carriers, one in the Atlantic Ocean and the other in the Indian Ocean, was accompanied by a certain degree of grandstanding on the part of the overseas territories administration in France. Contacted by Mediapart the Ministry for Overseas Territories said that “in his statement on March 28th 2020, the prime minister [Édouard Philippe] set out the missions of the helicopter carriers sent overseas. They will be used to look after patients, to ease the burden on hospitals there and also to help ensure logistical flow.”

This half-hearted defence contrasts with the frank views of the overseas minister Annick Giradin over what could be called the 'scandal of the mouldy masks'. Questioned by the Journal de l’île de la Réunion (JIR) newspaper about the provision by the health authority of old mouldy masks on the island, the minister said that “the distribution of defective masks is quite simply unacceptable. When this crisis is over, full light must be shed on this issue. When the time comes we will draw full conclusions from it.”

Honteux: À l’ile de la Réunion, ce sont des masques moisis qui sont livrés. Digne? Digne d’un pays comme la France ? À LaRéunion, à #Mayotte l’imprévoyance de l’Etat, l’inorganisation, la faiblesse des services publics orientent vers un drame d’ampleur. https://t.co/czlFJY3bBG

— younous omarjee (@younousomarjee) March 25, 2020

This statement directly challenges the Indian Ocean ARS or regional health authority as hundreds of protective masks covered in a film of green mould had been sent to La Réunion. The island now faces a major shortage of protective equipment, including for hospital staff and people working in retirement homes.

This kind of revelation just adds to the anger and fears of a local population who are only too well aware that what was known as “double labelling” - a practice in which different expiry dates were put on food products depending on whether they were destined for the overseas territories or mainland France - was only banned in 2017.

In such circumstances it is perhaps hardly surprising that magical thinking, familiar to local residents from a culture inherited from slavery and colonial violence, has made a comeback on La Réunion. The people on this island have had to endure physical constraints and the dismantling of their spiritual and cultural life ever since the start of their relationship with France, and they often veer between asking Paris for help and cutting themselves off from what they see as an obvious source of contamination.

On Mayotte, meanwhile, an astonished population has in recent days witnessed a complete role reversal in how the territory is perceived in relation to its neighbours. In the past the French authorities have tried to keep out migrants from the neighbouring Comoros islands who have made the perilous sea trip seeking the better health treatment and hospitals on offer on French-run Mayotte. But now that Covid-19 has hit Mayotte while so far sparing the Comoros, the Comoros authorities are taking delight in keeping virus-fleeing people from Mayotte on makeshift boats or kwassas-kwassas out of their own waters.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“In my view the story of kwassas being repelled in the other direction is not the key issue,” insisted Jamel Mekkaoui, director of the Mayotte branch of the French statistical agency INSEE. “The issue that's arising here is about respecting the lockdown, of staying at home, on an island where 40% of houses are made of corrugated metal, where 30% of homes don't have access to water, and where 57% of homes are said to be overcrowded and 33% of them are said to be seriously overcrowded.”

The islands that make up Mayotte, which has a population of close to 300,000, have around just ten intensive care beds and the population – half of whom are foreign, and some of them not in the country legally – live in poverty and in an atmosphere of extreme violence.

“The economic situation is almost more urgent than the epidemic,” said Jamel Mekkaoui. “The economy has stopped but life here for more than a third of businesses and citizens is about subsistence, survival. A non-negligible part of the population needs commercial activity to meet the basic needs of their family. A bit like in Madagascar or India, the action of going out each day to get food to eat is a challenge that in financial terms represents more than 9% of Mayotte's GDP. Staying at home is in reality a luxury … here that question takes on another meaning.”

Air links with Europe have been cut on Mayotte as on La Réunion. For residents originally from these areas who want to return home some unofficial routes still exist. But anyone who does use them will have to face a strict 14-day period of quarantine. And this practice revives long-buried collective memories of the terrible quarantine stations or lazarets on these lands where slaves coming from Madagascar or India were shut up after being taken off their ship.

The only ray of light to emerge from this swirl of emotions and trauma comes from the folk memory of the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu that initially killed a significant section of the population of La Réunion before ending as abruptly as it had arrived.

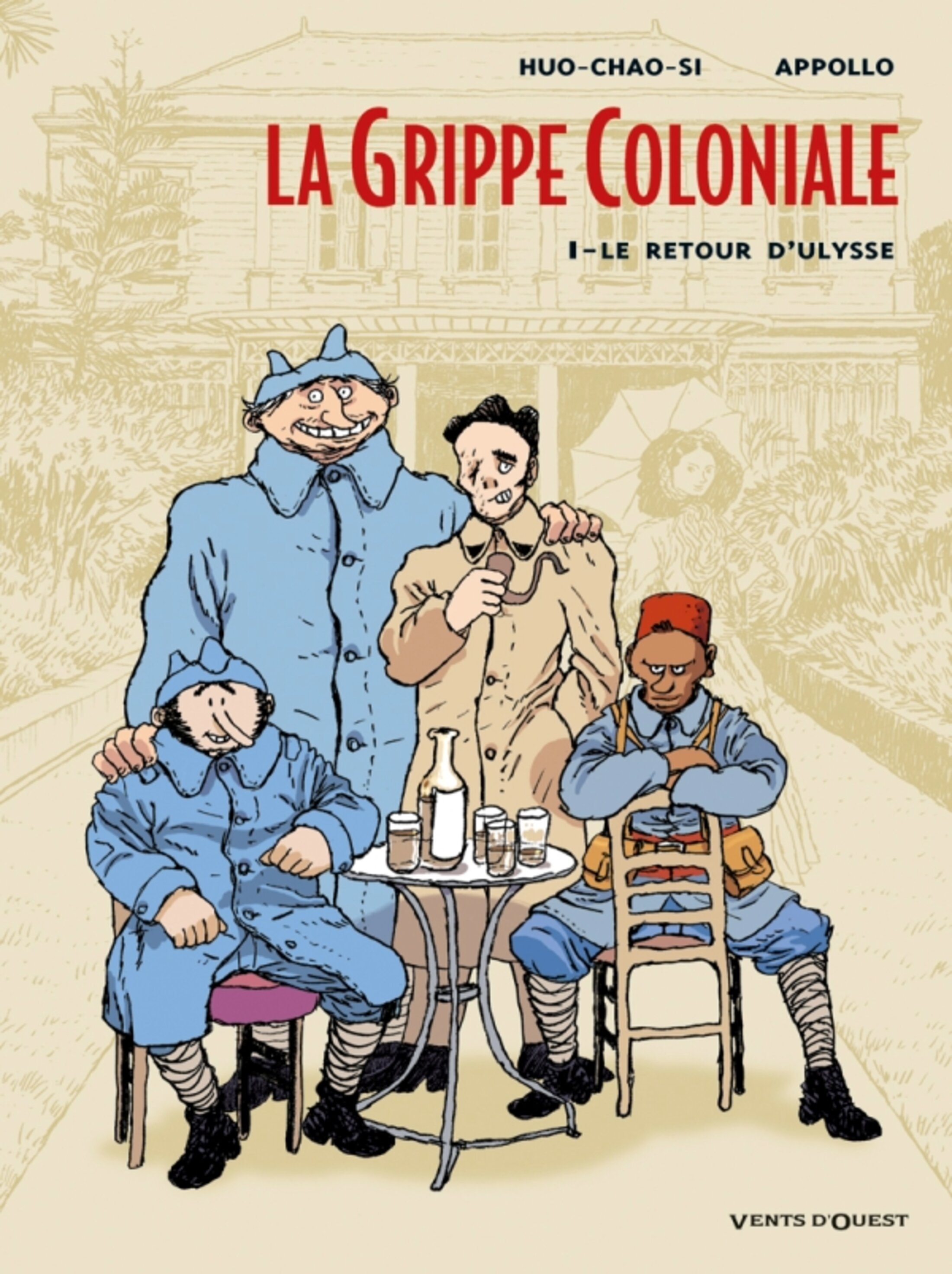

What saved the island was not protective measures or a treatment, still less aid from France; instead what came to its help was a cyclone which miraculously washed away the germs of the “colonial flu” - a term which later formed the title of an award-winning comic strip book 'La Grippe Coloniale' by Appollo and Serge Huo-Chao-Si.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter