The Rock is sitting on top of a volcano. In July 2005, when he became monarch of Monaco, Prince Albert II promised during his accession speech that he would reconcile “money” with “virtue”. Nearly 20 years later, the prince finds himself confronting the biggest internal crisis this city state – often known as 'Le Rocher' in French or 'The Rock' - has had to face for many years, perhaps ever, against a backdrop of endemic corruption and a merciless war between rival clans.

The situation has reached such a boiling point that no one seems able to say exactly how it will end, though everyone agrees on one thing: it will end badly.

This is a state riven by intrigue which for years smouldered like a dormant fire before now exploding into the open. The stakes for Monaco – a micro state which, covering just 2 km2 inside the French département of Alpes-Maritimes, is miniscule in size but gigantic in financial and money terms – are high. Albert II knows he is being monitored by the Council of Europe which in early 2023 criticised his administration's poor progress in the fight against the laundering of hidden money for which Monaco is reputed to be a hub.

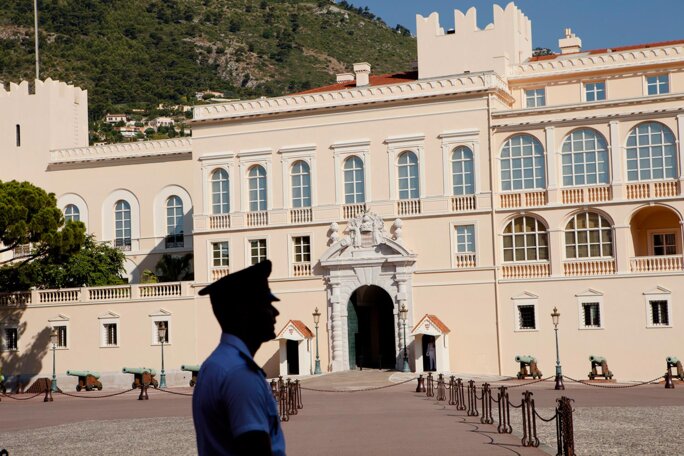

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The prince, who has in recent years made an increasing number of declarations about his intention to clean up the Augean Stables that is Monaco, now finds himself in a tight corner. The Rock is, of course, well used to financial scandals and to attacks from outside. No one there has forgotten the tax war that French president Charles de Gaulle waged against Monaco in 1962, to the point of declaring a blockade of the country. There is also the example of 2000 and the lacerating Parliamentary report written by two young socialist MPs, Arnaud Montebourg and Vincent Peillon, about financial crime in the principality.

But the prince doesn't now just have to start clearing up the mini-state in order to convince the outside world that it has changed. At the head of a 727-year-old dynasty, Albert II also has to douse the fire that has broken out at the very heart of the royal court, in his own palace. It is Monaco versus Monaco.

Civil servants and ministers have been dismissed en masse and a section of the prince's inner circle removed. Around 30 legal proceedings are currently taking place, divided between law courts in Monaco and Paris, with claims and counter-claims between the various warring parties. These cases are tearing apart the two camps who star in this political-financial thriller, one which underlines how crazy amounts of money can devour everything in its path.

But how could it be otherwise in such a small country whose incredible wealth has for decades been built almost exclusively on two surfaces as treacherous as banking and property, a state where tax is seen as an affront, and where institutional checks and balances have been corroded by venal behaviour?

A table of cannibals

There are two clans confronting each other. On one side there in the prince and his inner circle. On the other there are two past figures from the court; two friends, two outcasts. One of them is Claude Palmero, the former main assets manager for the principality – effectively the Crown treasurer - and the other is lawyer Thierry Lacoste, a childhood friend of Albert II.

The former clan accuses the latter clan (and those around them) of having schemed inside the very heart of Monaco's government, mixing their own private interests with those of the Crown and, worse, of even having profited from the prince's trust to enrich themselves to an exorbitant extent, while controlling local policy.

The latter clan reproaches the former clan (and those around them) of having compromised themselves with the giant Monaco property firm Pastor. They have even coined an expression to describe the hold that they say the Pastor family has on the Monaco scene: “pastorised”. Sworn enemies of the omnipotence that the Pastors have in Monaco – their property empire is valued in the tens of billions of euros – this clan feel they have been personally punished by Patrice Pastor, one of the heirs to the company.

It is like a table of cannibals in which each diner now appears to wonder who was the guest and who was the dish, with everyone denying the accusations of the rival clan.

The saga began to emerge in 2021 with “Les Dossier du Rocher” or “The Rock Files”, an anonymous release on a dedicated website of confidential messages highlighting the obscure practices of lawyer Thierry Lacoste, the principality's assets manager Claude Palmero and two other men, Laurent Anselmi and Didier Linotte, respectively the prince's former chief of staff and the former president of the Monaco Supreme Court. The objects of these leaks say they are the victims of hacking and manipulation and have taken legal action, and they suspect Patrice Pastor of being behind it – something he denies.

Three years later, in January 2024, the riposte came in the form of a series of articles in the daily newspaper Le Monde under the title 'Monaco: the secret notebooks' based on the contents of notes kept by Claude Palmero, who had been dismissed by the prince six months earlier. Claude Palmero had occupied the post of 'administrateur des biens' (ADB) or assets manager for more than 20 years, from 2001 to 2023, having taken over from his own father who had performed the same role for Albert's father Prince Rainier.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Claude Palmero spoke at length to Le Monde who portrayed him as the “man who knew too much” and who was got rid of after having “upset the interests of Monaco's main real estate developers” - in other words, the Pastor group. According to the newspaper, Palmero's notebooks show the “hidden reality” of the principality, including lavish spending by the prince's family, discreet investments in tax havens, property projects whose complexity matched the vast amounts of money at stake, and suspicions of all kinds of espionage.

The different faces of Janus

The inevitable happened and Palmero is now the focal point of the royal family's fury. They have promised new legal proceedings against the former assets manager and launched their own media response in the columns of Paris Match magazine, via a piece written by television presenter Stéphane Bern to mark Prince Albert's 66th birthday.

At the Palace, those who despise the former assets manager are fond of saying that he wanted to be king in place of the prince. Yet to the outside world there were no signs to suggest this: he went around with an austere bearing in unostentatious suits, and certainly did not flaunt himself with his anthracite-coloured Renault Clio car. Claude Palmero himself liked to highlight his simplicity and his obsessive prudence, which included an acknowledged aversion to computers – he does not want to leave any digital footprint of his activities.

But some traces of his immense prosperity, which has increased massively over the last 20 years, do exist. According to a series of confidential bank and financial documents dating from the end of 2021 and obtained by Mediapart, Claude Palmero has a fortune worth at least 110 million euros.

These sums of money, which he doesn't dispute, were divided been life insurance investment policies, hedge funds and property investment, and placed inside financial structures in which his own money was often mixed with that of the royal family, at the risk of some confusion. Three quarters of it – more than 75 million euros – was in the same company, called Janus. “I chose Janus as the name because there were two heads in the company, the prince and me,” Claude Palmero told Le Monde.

But email exchanges seen by Mediapart are open to a more nuanced interpretation of the facts. The emails show that the bank BNP, which dealt with Janus, had been worried since 2017 that Palmero himself might in fact be the “effective beneficiary” of the company.

“What about the fact that the company is supposed to be the investment vehicle of the [royal] family? Is that normal? In fact, Mr Palmero does seems to be the assets manager for the prince but the notion of 'benefits reverting to Mr Palmero' surprised me,” noted one BNP employee. The response of Claude Palmero's deputy was swift: “No connection with the family.” Other documents, dating from 2019 and 2022, confirm that Claude Palmero owned 100% of Janus, even though the company contained a part of the royal family's savings.

“At no time had the royal family been informed of the existence of the company Janus until an audit was carried out by the prince following Claude Palmero's dismissal [editor's note, in May 2023],” the prince's lawyers Jean-Michel Darrois, Cyril Bonan and Xavier Philipps told Mediapart. The monarch's entourage suggests this means that Claude Palmero had blithely mixed his own interests with those of the royal family's, to the point where it created damaging confusion, even bordering on a privatisation of the Crown's assets. Such claims infuriate Claude Palmero.

Questioned by Mediapart, Claude Palmero insisted that Janus managed the royal family's funds and his own at the same time, with the proportion belonging to the royal family being “around 95%”. He stated: “The company was created in the interests of discretion, in order not to reveal the royal family's investments, and it invested some of my personal funds too, because it would have been unnatural and reprehensible for a company owned by me only to manage the royal family's assets.” He continued: “Janus thus provided an alignment of interests in the investments, which any serious and committed manager must do.”

To support his comments Claude Palmero referred to an agreement that he signed while “worn down and under constant pressure” on October 18th 2023 and which allowed the royal family to take over Janus, but whose clauses are being kept secret by both parties. This now enables each side to give their own interpretation. “There can't be any theft. It's simply a collection of slurs which are just aimed at intimidating me and are part of the odious harassment campaign that has been deployed against me,” said Claude Palmero.

In the royal palace they take precisely the opposite view. “The prince never gave his consent to Claude Palmero taking an interest in or a stake in investments held by this company. The discretion invoked by Claude Palmero is just a false pretext. The lack of transparency that he created and which was never asked of him by the family was put in place solely for his benefit,” insist lawyers Jean-Michel Darrois, Cyril Bonan and Xavier Philipps, who point out that legal action for “breach of trust” was filed against Janus last September.

The 'Téléphérique' millions

In private, Claude Palmero repeats that “it was the Palmeros who made the Grimaldi's [editor's note, the name of Monaco's royal house] fortune and not the other way round!”. Nothing seems to annoy him more than the idea that he might have acted behind Albert II's back, especially concerning royal investments in tax havens. He cites as proof the royal family's full knowledge of offshore companies (two in Panama and three in the Virgin Islands) which Albert and his two sisters, Caroline and Stéphanie, inherited in 2005 after the death of their father. That transfer in fact resulted from a deed of division signed on October 5th 2005 before a public notary in Monaco by Albert and his two sisters, and which Mediapart has seen.

Monaco is an absolute monarchy whose prince is both the shareholder and the main head.

Today the prince's lawyers, who do not deny knowledge of the offshore investments, say that the prince had “asked several years ago and on several occasions for them to be closed and for the money to be repatriated to Monaco”. The lawyers said that the members of the royal household “did not imagine that they had not been listened to when Claude Palmero undertook to end this system, which had no reason to exist as the royal family has nothing to hide”.

After the assets manager left, the palace says it took numerous measures in the most opaque financial places in the world in order to repatriate the assets. “Since managing to get hold of the data that Claude Palmero refused to communicate, the new team has been able to implement the procedure to apply to close these companies,” the lawyers said.

Claude Palmero, who has a reputation for being economical with money but unsparing in his observations, often speaks of Monaco as an “absolute monarchy whose prince is both the shareholder and the main head”. But he seems less embarrassed by his own conflicts of interest.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

For according to documents obtained by Mediapart, Claude Palmero's name is at the heart of a case which is, to say the least, a delicate one. This is the so-called 'Téléphérique affair' named after the Monaco téléphérique or cable car company the Société Monégasque de Téléphériques (SMT) whose ownership was shared between the state and private individuals, including Claude Palmero and his family. The SMT has been planning since 1956 to set up a cable car in Monaco. This plan has not come to fruition but it nonetheless led to a lucrative property deal thanks to a transfer and sale of land – property is like gold dust in Monaco – as part of a project which also involved the state.

In 2017 the SMT sold land for 114 million euros land on the Boulevard du Jardin Exotique, which overlooks the royal palace, following a multiparty project drawn up with the state of Monaco. Documents in Mediapart's possession show that Claude Palmero had no concerns about being the private accountant for this project, as well as the principality's accountant (paid around 130,000 euros a year) in which role he went as far as correcting with his own hand several official documents involved in the deal, and also the recipient (along with several members of his family) of 23 million euros in dividends as SMT shareholders.

“When, on occasions, I invested in a personal capacity in a property project, the state or the prince were aware and were in perfect agreement over it, and were themselves interested parties and earned infinitely more money than me,” said Claude Palmero. He even considers that in the 'Téléphérique' deal there were “no conflicts of interest, quite the contrary, for there was a straightforward alignment of interests”. He insisted: “In the end the land was sold very considerably above estimate, to widespread satisfaction, because all the shareholders earned more than forecast, and several public and private shareholders (especially the state) profited from it a lot more than me!”

This position is in sharp contrast to the stance of the former minister for infrastructure and urbanism in Monaco from 2011 to 2021, Marie-Pierre Gramaglia, who received 13 million euros in dividends from the same transaction as a private shareholder. She told Mediapart that she recused herself from making any public decisions on the issue “in view of any conflicts of interests that might arise”.

Property rivals

During the different meetings that Mediapart held with Claude Palmero and his lawyers Marie-Alix Canu-Bernard and Thierry Lacoste, the former assets manager's number one obsession was always the same: Patrice Pastor. Palmero and those close to him are keen to raise the alarm over what they see as the harmful influence that the local property magnate has over the prince, his family and several members of the government.

In particular, Claude Palmero highlights a WhatsApp message he received in May 2023 in which Albert II told him of his dismissal in the following terms: “I am now practically obliged to speak out … to, in a way, signal the end of the party and to try to reassure many people here.” According to Claude Palmero the expression “ signal the end of the party” had been used just a few days earlier by Patrice Pastor.

In similar vein, the former assets manager at the palace said he was astonished to see that Albert II had become a civil party in a personal capacity alongside the Pastor group in a case involving “corruption” and “influence peddling” that did not involve the prince – as if their fate was linked in some irrational way. “The prince joined as a civil party in this case as in all cases in which his image and that of the royal family has been dishonoured, whoever the person implicated is,” said Albert II's lawyers, who added that “no one dictates his decisions to him, not the Pastor family nor anyone else”.

Meanwhile, the king of the Monaco property world also wants to be seen to be above the fray. Patrice Pastor's lawyer Antoine Vey even rejects the idea there is a “war of the clans”. He takes the view that the current situation merely results from the “decision of the sovereign to change the way the royal household works, and to remove some of his close advisers in relation to matters about which Mr Pastor has no comment to make, or any authority to make”. Antoine Vey said he considered that the “attacks” aimed at Patrice Pastor “basically seek to create a diversion to avoid mention of the actions of those who are bringing up his name and who are the subject of ongoing proceedings”.

Many observers in Monaco today suggest that Claude Palmero's attack on the Pastor clan would be more effective if he had not himself been paid by one of their property rivals, the Marzocco group.

According to documents seen by Mediapart, Claude Palmero has indeed personally received money from Marzocco, in particular 102,000 euros on November 17th 2022 and 200,000 euros on December 8th 2018, while he was working at the royal palace. The feeling about Palmero's position being undermined is strengthened by the fact that his two companions, lawyer Thierry Lacoste and the president of the supreme court Didier Linotte, have also worked for Marzocco, as shown by 'The Rock Files'.

When questioned by Mediapart about this, Claude Palmero confirmed his commercial relations with three companies from that property group. “I remind you that the assets manager is not a civil servant and comes under the jurisdiction of the prince alone. [The post's] status is a matter of debate but one cannot in any case say that it carries all the obligations of civil servants,” he said, insisting that he had worked as an accountant “in plain view”. He concluded: “I neither sought nor created this situation even if suited me as well as the prince.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this investigation can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter