Situated in the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean, and lodged between the east coast of Africa and the north-west of Madagascar, Mayotte shares the same culture, language, religion and colonial past as the rest of the Comoros archipelago. Yet following a referendum the people of Mayotte chose to become France's newest overseas département or county in 2011, meaning that politically speaking it is in effect part of France and, by extension, the European Union. As such it has its own unique destiny.

But though it faces major economic challenges, and is having to adapt to new cultural, administrative and fiscal rules from metropolitan France, the people of the two small islands that make up Mayotte lack the social benefits enjoyed by their counterparts in continental Europe. The main island, Grande Terre, may be situated in the “most beautiful lagoon in the world”, but many of Mayotte's 212,000 inhabitants crammed into just 374km2 of land are simply battling to survive in a département that is ravaged by poverty and poorly served in terms of social provisions, healthcare and tourism.

The United Nations and the African Union criticise the continued presence of France in Mayotte, arguing that it should be returned to the island nation of Comoros which became independent in 1975; the people of Mayotte had voted against independence in 1974. For its part, France emphasises the long historical and democratic ties which link it to its former colony. However, many experts believe that what really lies behind French interest in the islands of Mayotte is their important geographical and military location in the Mozambique Channel. In 2003 author Pierre Caminade set out France's motivations in his book 'Comores-Mayotte: une histoire néocoloniale' ('Comoros-Mayotte: a neocolonial history') published by Agone. Among them he highlighted how control of Mayotte gives France greater maritime influence, as its presence there and in surrounding small islands known as The Scattered Islands guarantees the country large exclusive economic zones (EEZ) extending up to 200 nautical miles into the ocean. This is one reason why France has the second largest EEZ in the world.

However, even though Paris's interest in the département may be far from altruistic, many people in Mayotte have learnt that describing French rule there as 'colonial' can be counter-productive. “In Mayotte it is better to speak of a fight for social equality with the metropolis rather than a struggle for de-colonisation,” says teacher Rivomalala Rakotondravelo, who is also secretary of the Mayotte branch of the teaching union the Syndicat National Unitaire des Instituteurs Professeurs des Écoles (SNUipp). “If you use that term you get shot down. There is still such a fear of being thrown out of the French Republic and placed under the authority of the Comoros that it is often considered preferable to not speak too loudly and to kowtow. But the feeling of submission to the French state is very strong.” This submission is not always easily digested in France's only Muslim département, where law based on traditions and custom is slowly having to give way to common law.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“Before becoming a département we were unable to tell the [French] state: careful, this is our model of society,” says Mohamed Moindjié, director of the local National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (CNAM) and deputy mayor in Mamoudzou, the capital of Mayotte. Since the change in status in 2011 – Mayotte had previously been an overseas collectivity or authority – cultural divisions and growing inequalities have eroded society. In spite of this, in public the 'Mahorais' - as people from Mayotte are known in French – continue to claim that they are “proud to be French”. In private, though, it is a different story. Under the cloak of anonymity people speak freely and say they feel burdened by a suffocating administrative rule which has colonial and segregationist undertones.

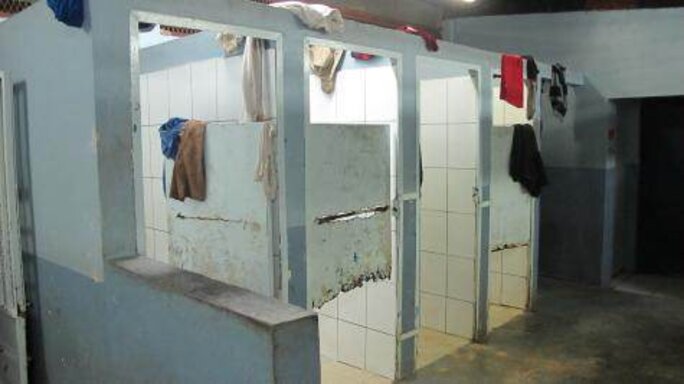

These undertones can be felt as soon as you set foot on the island. Apart from an increase in violence, and the sad looks that are barely concealed by the smiles of an exhausted people, what most strikes new visitors are the social divisions. The majority of people from metropolitan France and Mayotte's middle classes live cooped up in protected zones, expatriate districts dubbed mzungus land ('White people’s land') by young people. Elsewhere thousands of locals and Comorans have to survive, often without water or electricity, in bangas, little houses or shacks with metal roofs heated by the burning sun, crammed into the biggest shanty towns in France. In whole stretches of the main island you do not come across a single expatriate. There is an official curfew from 7pm and white people are advised not to go out alone. Yet every day one is astonished by the respect shown by the children on Mayotte for people from metropolitan France, who are addressed or referred to as 'Monsieur' or 'Madame'.

Apart from the département council – known as the conseil général – the metropolitan French run virtually all the administrative bodies on Mayotte. “Some administrative practices experienced by the population can make you think of a colonial system,” admits the Socialist Party (PS) senator Thani Mohamed Soilihi, who himself prefers to “criticise the treatment to which our land is subjected. To speak of colonialism would be to admit defeat”. However, just a few days on Mayotte is enough to show just how unusual some of the administrative practices are.

- Children expelled from French territory

Each day dozens of Comorans flee their country, which is classified as the 26th poorest in the world when measured by gross domestic product, to get to Mayotte just a few dozen kilometres away. But since the introduction in 1995 of the so-called 'Balladur visa', named after the then-French prime minister Édouard Balladur, which restricts the free circulation of people in the archipelago, the Comorans have no choice but to make clandestine, expensive and perilous journeys to get to Mayotte. Among them are hundreds of children, some as young as five, who make the crossing unaccompanied on board a kwassa-kwassa, makeshift boats that are sometimes intercepted by the border police the police aux frontières (PAF).

Usually, in metropolitan France at any rate, unaccompanied minors are protected from being expelled. “Under French law no child can be locked up or removed without being accompanied by a legal representative,” says Marie Duflo, secretary general of the immigrant advice and support body the Groupe d’Information et de Soutien des Immigrés (GISTI). However, according to GISTI's estimates out of the 19,991 people expelled from Mayotte in 2014 (up from 15,908 in 2013), a quarter were children. Each month the PAF succeeds in getting round the rules by a unique procedure of “fictitious affiliation”. “You have to see it to believe it,” says Marie Duflo, who is deeply concerned about the practice. When a child has arrived clandestinely without a responsible adult, the prefecture decides, without any consultation, to 'allocate' that child to an adult who arrived on board the same vessel. It does not matter if that person is unknown to the child, and that there is no parental or family link. Once they have been affiliated in this way, the 'accompanied' child is then ready to be placed in a holding centre before being unlawfully sent back to the Comoros, sometimes within just a few hours. The migrants' rights group the Comité Inter-Mouvements Auprès Des Evacués (CIMADE) and GISTI have also seen this method applied in cases where one of the child's parents resides lawfully on Mayotte. They say such methods are carried out in line with “the silently-conducted policies” of the French authorities.

“There is no shortage of exceptions in practice and law in Mayotte … and it leads to many abuses of children's fundamental rights,” concluded the official defender of children's rights in France, the Défenseure des Enfants, in a report back in 2008. France's top administrative authority, the Conseil d'État, has also condemned the “clear unlawfulness” of the current practice on several occasions, for example in rulings on October 25th, 2014 and January 9th, 2015, after groups fighting for the rights of foreigners referred cases to it. However, as Marie Duflo points out, the Conseil d'État merely urged the authorities to verify “as far as is possible” the child's identity in such cases. This order has very limited impact in a land where “removals are carried out on an industrial scale”, says Duflo. According to the daily newspaper, Le Journal de Mayotte, some 183 minors were sent back to the Comoros in the space of just three days in February this year.

- French is a second language

People do not speak French in daily life on Mayotte. In taxis and in supermarkets, on café terraces and on local radio and television, you hear Shimaore and Kibushi, the main local languages in the region. Only in the schools and administrative offices do you hear French, where it is obligatory.

Paradoxically, classes in the schools are taught in French but the language itself is not taught. The result is that one in three children who have been to school are illiterate. “Many of them still go through their entire time at school without mastering the basics of written French,” noted a report from the French statistical agency INSEE in February 2014. On Mayotte itself many people are critical of the current situation in the schools. “The pupils quickly have to renounce their language and their culture. Without offering them any point of reference in return, without allowing them to have any effective learning [of French], they have a form of self-denial imposed on them. The children are all over the place,” says Isabelle, a former teacher who is today a bookseller at Passamainty, a village in the centre-east of the main island.

Louis – not his real name – a philosophy teacher at a secondary school in Sada, a village in the centre-west of Mayotte, believes that the absence of measures to help youngsters learn French at the beginning inevitably leads to them feeling lost, and that they develop a feeling of subjugation and of being dominated. As proof he cites the confusion and questions raised each week in school essays. One final year pupil 'Amani' – not his real name – wrote recently: “It's the reason why many of us fail: identity and language. It's not a good idea to impose a language on others. It is better to exchange. We would all be equal, full of learning, bilingual and even trilingual. Our identity is as precious as the black gold of Saudi Arabia. Our language is being guillotined by the colonists' language. We have to change the rhythms of our lives completely.”

On top of the suffering of young people, Rivomalala Rakotondravelo points to the humiliations and difficulties faced by the local Mayotte teachers. “We are forbidden to use our language with pupils, even if they find themselves at an impasse and unable to understand,” he says. “Whatever happens, you have to speak French. But that's impossible. So some colleagues hide themselves away when they want to explain certain points. If they are surprised by their superiors they may be insulted, and accused of not knowing how to teach in French.” Rivomalala Rakotondravelo adds: “Regional languages have a real place in all the other French départements but in Mayotte they have decided to deny them completely.” It is a view shared by lawyer Fatima Ousseni, who sees the institutional rejection of the Mayotte languages as an inevitable brake on the development of society as a whole. “In the Antilles [editor's note, meaning the French islands in the Caribbean] when they stopped treating creole as a pariah language, people started to advance,” she says.

Like all départements, Mayotte is bound by article 2 of the French Constitution which imposes monolingualism and demands that regional languages are treated simply as secondary languages. Yet according to linguist Michel Launey, honorary professor at Paris 7 university and a researcher at the Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD) in French Guiana, the situation in Mayotte is unique, as here the regional language, which is in fact people’s mother tongue, has been rejected by the French education authorities. “The majority of the children are monolingual in the local language when they start school,” he points out. “This scenario has disappeared in metropolitan France. And in other French overseas territories adjustments are made. In Guiana, New Caledonia and in Polynesia they have put measures in place that help in the learning of French. In Mayotte they apply methods that exclude the mother tongue. It is denied and rooted out.”

As a result Launey decided to alert the French language department at the ministry of culture, the Délégation Générale à la Langue Française et aux Langues de France (DGLFLF), and the ministry of education in a memo that underlined the special circumstances of Mayotte and the dangers of the current methods employed there. So far his memo has not received a response. In the meantime various groups and associations on the ground are urgently demanding that their local languages are officially recognised and that lessons in French as a foreign language are introduced in all schools. Meanwhile in the supermarkets and cafés of Mayotte the Mahorais continue to offer abject apologies for not being able to express themselves in French.

- Expatriates on a mission to civilise

“When you see the salaries that the mzungus [white men] get for coming here, you shouldn’t be surprised that the island is divided between Whites and Blacks. They only come to Mayotte to make money. Then, when they've seen enough, they go,” says Raldgy, a secondary school pupil in Kaweni, with evident disgust.

In his village youngsters with dark circles under their eyes, clad in threadbare tee-shirts and shorts, are doing well if they can buy a tin of sardines every day at the local grocery store. Sometimes they just have to make do with sifting through enormous sacks of rubbish taken from communal bins. Just a few hundred metres away the expatriates are filling their shopping baskets with imported goods at the local supermarket.

In Mayotte the majority of senior public officials – categories A and B – are still expatriates from metropolitan France. All of them, from those working in education to staff involved in health care, benefit from the higher pay that is traditionally granted to make up for an area's lack of appeal, compensating public servants for the distance from home and the higher cost of living. When they are posted to Mayotte civil servants thus get part of their rent paid and a tax-free overseas allowance equivalent to 23 months extra pay over two years. For many people in Mayotte these pay perks are scandalous, and they point to the negative effects they cause, while noting that they themselves do not even have access to the necessary training to become a civil servant.

The first negative impact that locals complain about is the impact of the high salaries and allowances on inflation. Local residents accuse the major retail outlets – Sodifram, Somaco and Jumbo – of indexing their prices to the expatriates' pay. They claim that the cost of living, which is made worse by the policy of importing many goods, would be much lower if the civil servants were not rewarded so handsomely.

This issue was raised back in 2003 by an MP from the right-wing UMP party, Marc Laffineur, who, in addition to highlighting the lack of equality it leads to, criticised the impact of “extra pay in the public sector” on local prices. Back in Paris, officials who work for the minister for overseas affairs, George Pau-Langevin, are very aware of the drawbacks of the current system. But they insist that the need to compensate for the lack of an area's appeal justifies the absence of any reforms so far. “It's difficult, there are some posts we can't fill,” says one official. “Even though we're very aware that the system in force is very imperfect, and that it causes local inequalities, no one has yet found a better system.”

Another grievance is what is seen as the humiliating condescension of expatriate public servants towards locals. People on the island criticise the behaviour of many officials, which they consider is a direct result of the difference in salaries and the gulf in respective living standards. “These allowances are indecent and have very obvious negative effects,” says Louis, the teacher from Sada. “Some colleagues have persuaded themselves that they are on a mission to civilise, that they have to bring the Enlightenment to the Mahorais people, and that without them the island would sink into chaos, and that it is precisely for this reason that they are well paid.”

This observation is shared by the deputy mayor of Mamoudzou, Mohamed Moindjié, who emphasises that the colonial inheritance still lives on. “Some Whites rule here like in colonial times. They act as if we should be governed, supervised and mollycoddled.” The linguist Michel Launey notes: “Everywhere else, overseas [French] metropolitan officials are careful and respectful with the people with whom they deal, at least on the surface. In Mayotte there exists a colonial-style arrogance.”

The expatriates' long-standing benefits have not escaped the notice of France's audit court, the Cour des Comptes, which in its last annual report, published in February (see pdf of report here), attacked the “inextricable labyrinth” of the extra payments received by all state civil servants posted overseas. The audit court demanded a “wide-ranging reform” and stated that while extra pay for personnel (which reached 1.178 billion euros in 2012) made up more than 8% of total French state overseas expenditure, the “differential in the cost of living bears no relation to the scale of the extra payments”. It called for a different way of persuading civil servants to work overseas through incentive measures that were “non-financial”.

- Land ownership

Four years after their homeland became a French département, the people of Mayotte feel that they have been overwhelmed by changes. On islands that are traditionally ruled on the basis of custom-based laws, each day the Mahorais people are discovering new rules governing taxes - for example income tax, residential tax, property tax and television licences – as well as fresh measures that are part of the transition to common law. When faced with these new fiscal obligations the worried response of local people is: “It's impossible, we can't...” It is a concern that constantly crops up in conversations.

At the heart of the problem is a big shake up of property rights and ownership relating to Mayotte's shores. Traditionally, property rights on the coastal fringes have been governed by local customs which recognise collective use of areas by families, without those plots being officially recorded or registered. The process of updating property rights to meet metropolitan standards began in the 1990s but has recently taken a new turn. Previously local people were able to get permission to stay on a site temporarily under what was called an autorisation d’occupation temporaire (AOT). “Today the state considers that it is not its role to be a landlord in relation to individuals. The AOTs are no longer being renewed, people are being asked to buy,” Philippe Chauliaguet, the local representative of France Domaine, the section of the budget ministry which handles state-owned property, told Le Journal de Mayotte.

These purchases are overseen by the prefecture and are dealt with on a case by case basis to establish the right price in terms of the market, the use of the land and the buyer's resources. Anger is starting to mount as some of the poorest people, unable to afford a plot at any price, face being ejected from their ancestral land. Even those who have been fortunate enough to buy their land are now wondering how they will find the extra money to afford the new property taxes.

It is estimated today that there are some 20,000 people on Mayotte who do not have official title to their homes. “In the long term this regularisation will end up removing the Mahorais from their homes, even though here land is sacred,” says Hafidhou Ali, 28, a member of one of the remaining parties supporting independence for Mayotte, the Front démocratique. He adds angrily: “Turning [Mayotte] into a département will inevitably lead to catastrophe, and I'm very afraid that the people will realise this too late.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter