Few have heard of the International Monetary Fund's substitution account. The mechanism, proposed 40 years ago, never saw the light of day and yet, argues Philippe Ries, this is an instrument that would have offered, here and now, a way out of the eurozone debt crisis.

-------------------------

In the current economic situation, there is nothing more depressing than finding that problems in the functioning of the international monetary system, which lie at the root of a series of financial crises, were anticipated in the past and that possible solutions were put forward and considered.

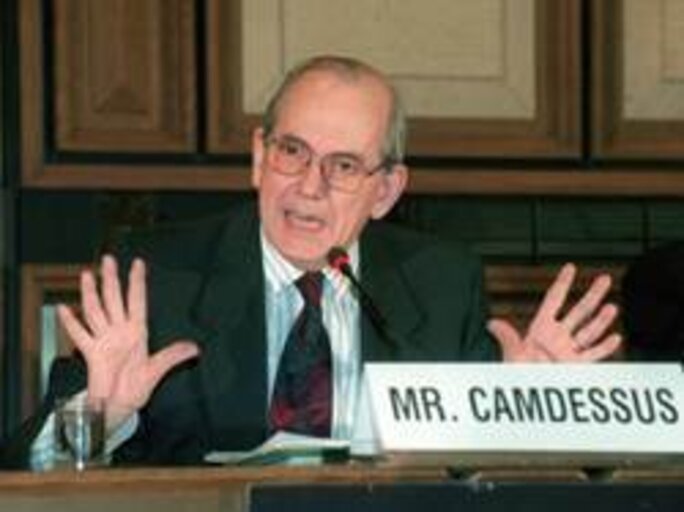

But as a rule these came to nothing because of a lack of vision by policymakers. The International Monetary Fund substitution account, an idea that was contemplated after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, provides another example of this, just like the proposal for a sovereign debt restructuring mechanism. The eurozone's inability to overcome a difficulty that is A substitution scheme would be a very important instrument to help the off-market diversification of reserve holdings." It is no coincidence that the speech was delivered in Beijing.

He added: "The bad memories of the abandonment of the project of a substitution scheme in 1980 shouldn't deter the authorities from revisiting this issue, remembering as a matter of fact how close they have been to an agreement in the earlier occasion." But the recommendations of this expert were once again ignored. As you would expect, eurozone politicians did not see any of this coming and ended up being humiliated at the G20 summit in Cannes when, in vain, they held out a begging bowl to the leaders of the emerging economies.

Economists predicted that a system with the dollar as the only international reserve currency would lead to major imbalances, from the moment on August 15th 1971 when Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold to stop the US's gold reserves leaving Fort Knox for its creditors.

These imbalances included a build-up of deficits in the US which, being able to finance these deficits in its own currency, faced no budgetary constraints, along with a build-up of dollar reserves by US creditor countries, far beyond levels needed to finance trade. There was also the risk that the US might deprive the world economy of liquidity if it suddenly attempted to correct its deficit, or that the dollar could collapse if doubts grew about the ability of the US to meet its debt repayments.

The substitution account was to have enabled surplus countries to diversify their reserves by depositing dollars with the IMF in exchange for Special Drawing Rights, the IMF unit of account based on a basket of currencies (see more here). SDRs were created in 1969 to offer an alternative to the dollar, which could be managed collectively rather than just for the needs of the US. But they never really took off, partly because of US resistance, although the financial crisis that started in 2007 finally led to a substantial, but still inadequate, increase in the Fund's resources.

IMF at heart of new global economic governance

If the substitution account existed today, China and other emerging economies would be able to deposit some of their dollar holdings in it without any risk of the sort of exchange rate instability that would result from a direct switch into euros. The dollar has a disproportionate weighting in the reserves of these countries and this is a legitimate source of concern for them. China's reserves alone are worth 3,200 billion dollars while Asia as a whole has reserves of 6,000 billion dollars.

A substitution account would also enable the recently-created European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) to get from the IMF the hundreds of billions of euros it will need if Italy is the next to be sucked into a liquidity crisis, a risk that is growing by the day. Instead the EFSF is struggling to raise a few billion on the markets and its risk premium is now above that of France.

This would of course not be without strings, but it would not involve having to negotiate with Beijing, Moscow or Brasilia, make politically embarrassing deals or receive a public telling off from the new champions of global growth. It would also be easier for the lending countries, where public opinion finds it hard to accept the idea of poor nations openly giving aid to those that are much richer.

In his speech in Beijing, Michel Camdessus said that the main bone of contention that prevented the substitution account from seeing the light of day related to the question of "the distribution among members of the exchange risk which is inherent to such a scheme". He wondered whether the holders of dollars, the US or the IMF should take on this risk, and concluded that it would be "more expedient to adopt a fully multilateral approach by inviting the IMF, entrusted with enhanced responsibilities to monitor and promote the stability of the system and endowed with gold reserves and quotas [contributions from member states] to accept to bear itself this risk, with the strong assurances of support from the membership [...] if its own financial situation was endangered". Camdessus saw the creation of the substitution account as just one element which would put a thoroughly reformed IMF at the heart of a new system of world economic governance.

Why call on the IMF when the eurozone itself theoretically has sufficient financial resources to come to the aid of members facing difficulties, particularly if they are fundamentally solvent, as in the case of Italy if not Greece? For the same political and technical reasons that made it evident as early as January 2009 that the Eurogroup would have to ask the IMF to come to its rescue. And also because it is well understood that it is in the interest of other players in the international monetary system that the eurozone debt crisis does not degenerate into a global disaster.

The threat still hanging over the dollar

Of course for some, particularly in France, a simple solution would involve the monetisation of European sovereign debt by the European Central Bank, which would be allowed to make unlimited purchases of debt securities that investors no longer want, at issuance and not just on the secondary market. This is contrary to the letter and spirit of the EU treaties, although the ECB's limited and temporary buying of peripheral country bonds since May 2010 already represents a deviation from the treaties. But it remains wishful thinking as long as Germany remains opposed to the idea.

Germany knows that the final bill for any holes in the ECB's balance sheet, which has more than doubled since the start of the crisis, will land on the table of the governments, who are the financial guarantors of the national central banks making up the Eurosystem. It also knows that a move to printing money would mark the end of any efforts by the rescued countries to finally restore order to their public finances. This would be a government version of moral hazard. This is exactly what happened with the Berlusconi government, until growing market pressure led to Italy being placed under the oversight of the IMF and then to the fall of this old comedian who no-one found funny any longer.

And even though all eyes are presently on the eurozone, we must not forget that in the background there is still the threat of a brutal decline in the dollar. The fundamentals of the US economy are no better than those of the eurozone, its external debt much higher and institutional bottlenecks just as great. US creditors have legitimate concerns about the medium- and long-term effects of the monetary policy carried out by the Federal Reserve and its QE1 and QE2 quantitative easing measures and are on the lookout for safe havens, which explains the yen's surge to new record highs as well as the rise of the Swiss franc, Brazilian real and the price of gold.

As Fred Bergsten wrote in December 2007 in The Financial Times when he dusted off the idea of the substitution account: "Since foreign dollar holdings total at least 20,000 billion dollars, even a modest realisation of these desires could produce a free fall of the US currency and huge disruptions to markets and the world economy. Fears of such an outcome have risen sharply in both official circles and the markets."

Political elites have learnt no lessons

Bergsten, director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said there was widespread international agreement at the end of the 1970s on the idea of an IMF substitution account, which was even backed by US congressional leaders. "It failed only because the sharp rise in the dollar that followed the Federal Reserve's monetary tightening of 1979-1980 obviated much of its rationale, and over disagreement between Europe and the US on how to make up for any nominal losses that the account might suffer as a result of further depreciation of dollars that had been consolidated," he said. This takes us back to the exchange risk question identified by Michel Camdessus.

The idea of a substitution account obviously raised numerous legal, operational and financial questions which were examined in detail in an exhaustive study published in 1979 by the New York Federal Reserve. But in hindsight the political efforts required and the risks involved seem derisory relative to the turmoil caused by the chronic instability of the international monetary system, which ultimately led to the global catastrophe that started in the summer of 2007.

This of course assumes an acceptance that global imbalances played a determining role in the sequence of events that led to the current crisis. And as Bergsten stressed in 2007: "A substitution account would not solve all international monetary problems nor would it suffice to restore a stable global financial system." Nor would it spare the EU and zone euro from a radical rethink of its way of life.

But it would respond here and now to the practical problem of how to put in place the best possible system to enable countries or currency areas that are temporarily short of liquidity, as is the case with part of the eurozone, to get what they need from countries that are looking for a safe place to invest their surplus reserves.

We must not forget that the present situation is similar to that which led to the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 and of course the subprime crisis in the United States.

But it is no surprise that the political elites of the so-called advanced economies have learnt no lessons from events which they do not know enough about, and which hold no interest for them. Counting on IMF managing director Christine Lagarde to relaunch this important area of work would be like expecting EU Commission president José Manuel Barroso to take the initiatives which would help the eurozone out of the dead end in which it currently finds itself.

-------------------------