Claude Chabrol, the celebrated and revered French film director who died in Paris on September 12th, aged 80, remains an enigma for many. Despite an unusually prolific directing career, making more than 50 films since 1959, he was a very private man who shunned the traditional gloss and glamour surrounding the film industry.

Jean Douchet is an authority on French cinema, himself a director, critic and university lecturer, who also runs the ciné-club, a projection and debating centre at the Paris-based Cinémathèque française. He remained a lifelong friend of Chabrol, ever since the two men first met in the mid-1950s, when they worked together as film critics on the French cinema magazine of reference, Cahiers du cinéma.

"What happened with Chabrol is what would have happened with Godard or Rohmer," Douchet told Mediapart. "We don't see each other for years but when we meet up again the conversation picks up exactly where it left off, and it's always about cinema." In this interview, recorded shortly after Chabrol's death, Douchet talks about the work and personality of one of France's greatest film-makers.

Q: The thing that stands out above all from Claude Chabrol's films is his harsh take on the French middle classes. Is that appreciation too summary?

J.D.: I would say that, for French cinema, he was the equivalent of Fassbinder in Germany, Fellini in Italy, Almodovar in Spain, or even a Hitchcock during his British-based period. He was among those who were interested by the vulgarity of their country, and who film this vulgarity with beauty and grace. Without that, vulgarity can very quickly become quite scary.

From a sociological point of view, Chabrol filmed neither monarchs nor the people. He placed his characters within a quite restricted [social] range, between the lower and upper middle classes. A little like Eric Rohmer. Yes, of course, he filmed [stories about] the French bourgeoisie. But it was more complicated than that. He filmed that feeling of helplessness people get when they cannot become what they would like to be, when they cannot reach what they aspire to be. He worked on this form of regret which, when someone become conscious of it, leads to a sort of human mediocrity.

This is evident in A double tour (1959), a magnificent film, perhaps a little too mannered, which I saw again on television just a few days ago. In this film, beauty is unreachable.

(A double tour. A husband plans to leave his wife to join his mistress, but his son opposes him. In the setting of a tormented bourgeois family, each man discovers the image of his own mediocrity, reflected in their relationships with the beautiful and generous mistress.)

'A serious being who wore a mask'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

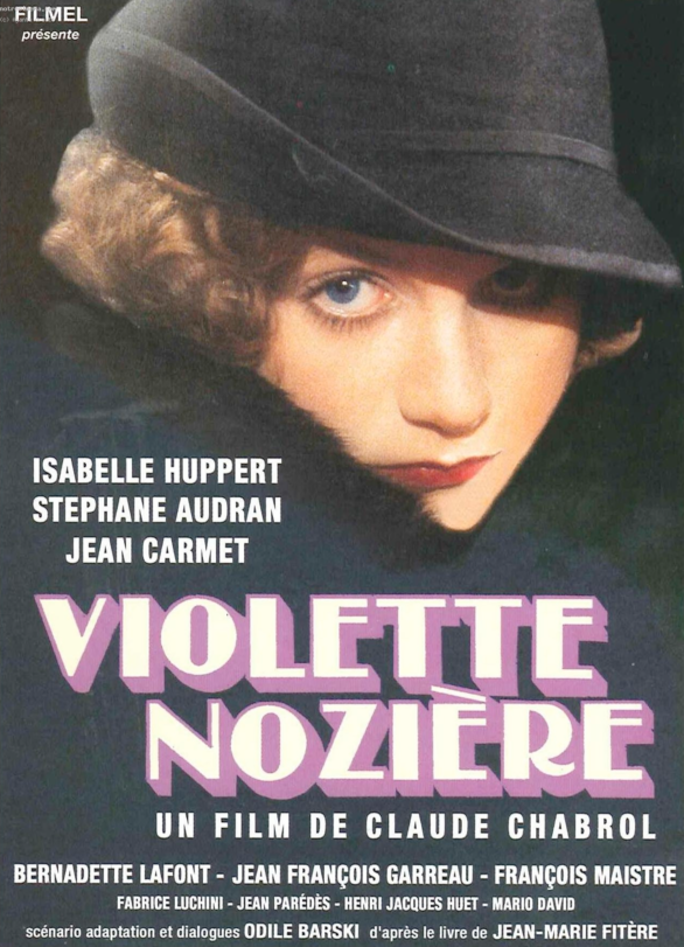

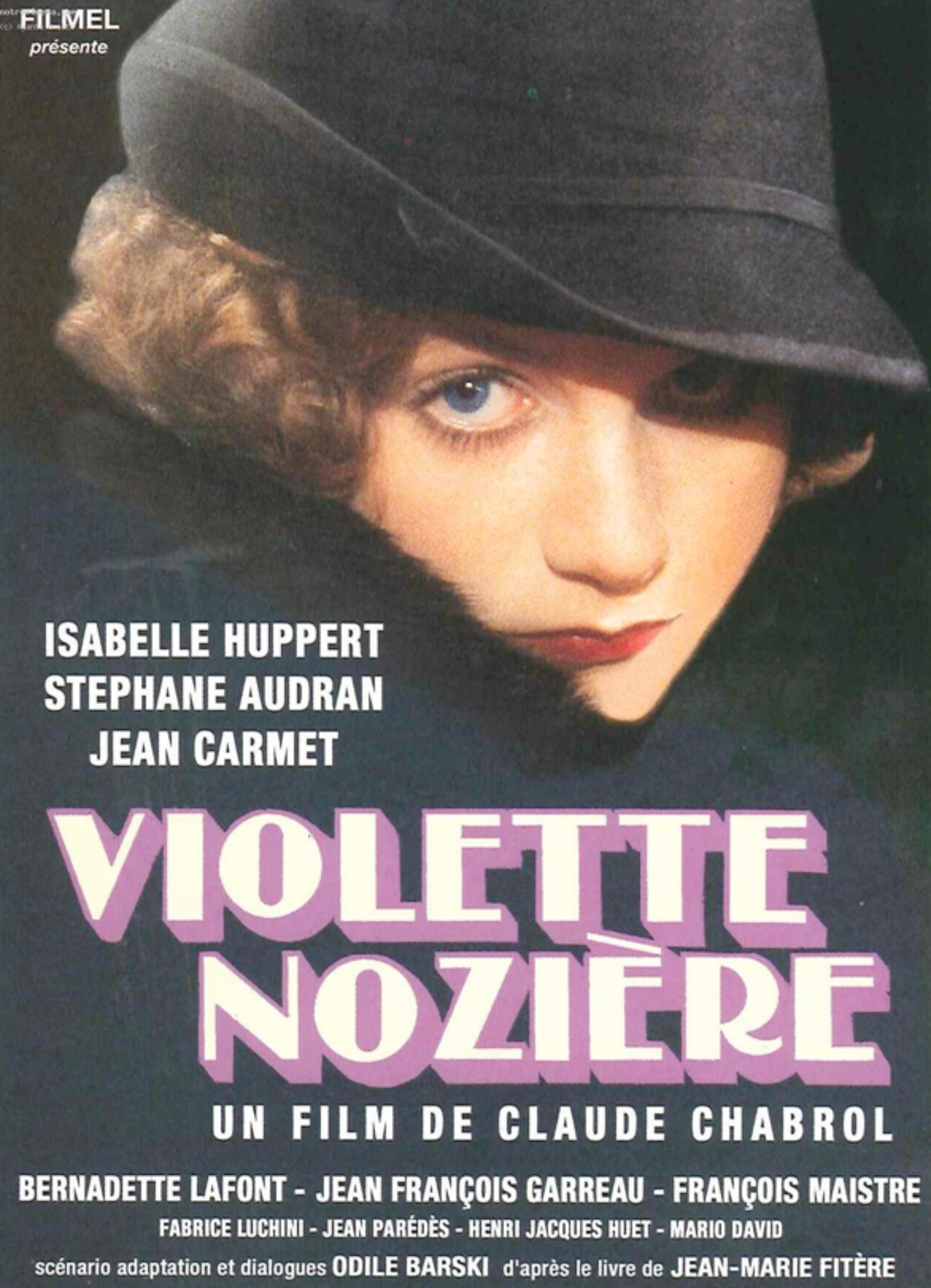

J.D.: In Violette Nozière [1977, about a teenage girl, played by Isabelle Huppert, who poisons her parents], Isabelle Huppert is in the role of someone who simply seeks a bit of social happiness. With Claude, downfall comes from not knowing who one really is, [when] happiness comes from other people's dreams, from society. Which can only produce misfortune. It's all the same a pretty powerful idea. Claude was never an aggressive person, but he enjoyed having a bite. We used to throw punches at each other, but in fun.

Q: He also left an image of a director who blurred the frontier between cinema and television, an adept of simplicity, who rebelled against the notion of being 'a great cinema director'.

J.D.: That's entirely untrue. On this subject, he copied Hitchcok. Claude made people think he was someone who amused the gallery, someone who told jokes. But this was not at all the case. He wore a mask. He was a serious being, but who didn't take himself at all seriously. His films were calculated, very precise. He knew exactly why the person on the left of the screen would pass to the right, at which moment, and how long it would take them. He thought about every aspect of setting up a scene. It was on this same subject of setting a scene that he became opposed to Jean-Luc Godard. Godard wanted cinema opened up to absolute art. Claude wanted to recount, with art, things that are above all visible and legible."

Q: About his first film, Le Beau Serge (1958), which marked the beginnings of the [French] New Wave, you wrote in the magazine Cahiers de Cinéma that it was "the story of a reanimation, in the sense of "rendering breath back", "rendering life", in contrast to the story of Cousins, which was about smothering, asphyxia."

J.D.: Like every major cinema director, Chabrol was an artist over the long term, of temporality. The rhythms and breaths within sequences are very important for his style of cinema. This is very clear in Le Boucher [The Butcher, 1969]. And Landru [Bluebeard, 1963], from this same point of view, is also quite remarkable. Chabrol developed an extremely wide variety of approaches, from the clownish to the ridiculous. The only area he didn't venture into was tragedy. But he has filmed every type of drama, and which were more or less amusing.

Le Beau Serge: François (Jean-Claude Brialy) returning to his native village, meets up with an old childhood friend, Serge (Gérard Blain).

"He sometimes made crap, but never void of interest"

Q: Did Chabrol have a plan to his career?

J.D.: Yes. He always stayed true to this idea of an economic policy, an idea that came from the Cahiers du cinéma. This was the idea that it was the money put into a film that decided its aesthetic result. That it was with economic constraints that one could produce the aestheticism. Like all the directors who came from the Cahiers at that time, he stuck to that principle. So he had, in that sense, a plan.

He at first wanted to be his own producer, and not direct short films but go, straight away, onto feature-length films. He was the first of the Cahiers team to make a feature-length film with Le Beau Serge. Obviously, he soon became bankrupt and so he went looking for producers. There were five or six different ones over his lifetime. He didn't cost a lot. In any event, he wasn't paid what could be expected for a director of his reputation. That left him in peace, including when he shot third-grade films during the difficult periods.

For example, during the 1970s, when he cast Roger Hanin [Le Tigre aime la chair fraîche, 1964, and Le Tigre se parfume à la dynamite, 1965]. He sometimes made crap, as he called it, but never anything that was void of interest. He never made anything that was appalling.

Q: You are also an ardent admirer of Chabrol's last two films, which were virtually unrecognised by critics, including Bellamy [2009], with Gérard Depardieu.

J.D.: Bellamy is a film that he himself believed was important, and which didn't get the reception it should have had. It is a very great film. Together with La Fille coupée en deux ['A girl cut in two', 2007], these are two films made at the end of a career, when Claude wasn't trying to show what he was capable of but rather to talk about things both more personal and more general. A reflection about life, about the world, about who we are.

He didn't disagree with what I told him when Bellamy was released, that I saw in this film a confession about who one is, a reflection on the old notion of vanity. It is not a testament of a film, I hate that description, but it is a weighty film.

English version: Graham Tearse