Renault chief executive Carlos Ghosn is, it would appear, a man above everything, already beyond criticism and self-questioning, and now above the opinions of his shareholders. While he hasn’t gone quite so far as Lloyd Blankfein, the CEO of US bank Goldman Sachs who infamously pronounced in 2009 that he was doing “God’s work”, Ghosn’s choices and behaviour suggest that he is not far from sharing the same view. After all, a talent as immense as his cannot reasonably be called to account, and much less so submit its remuneration to review by the carmaker’s annual shareholders’ meeting.

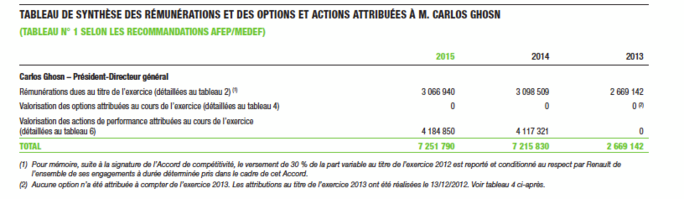

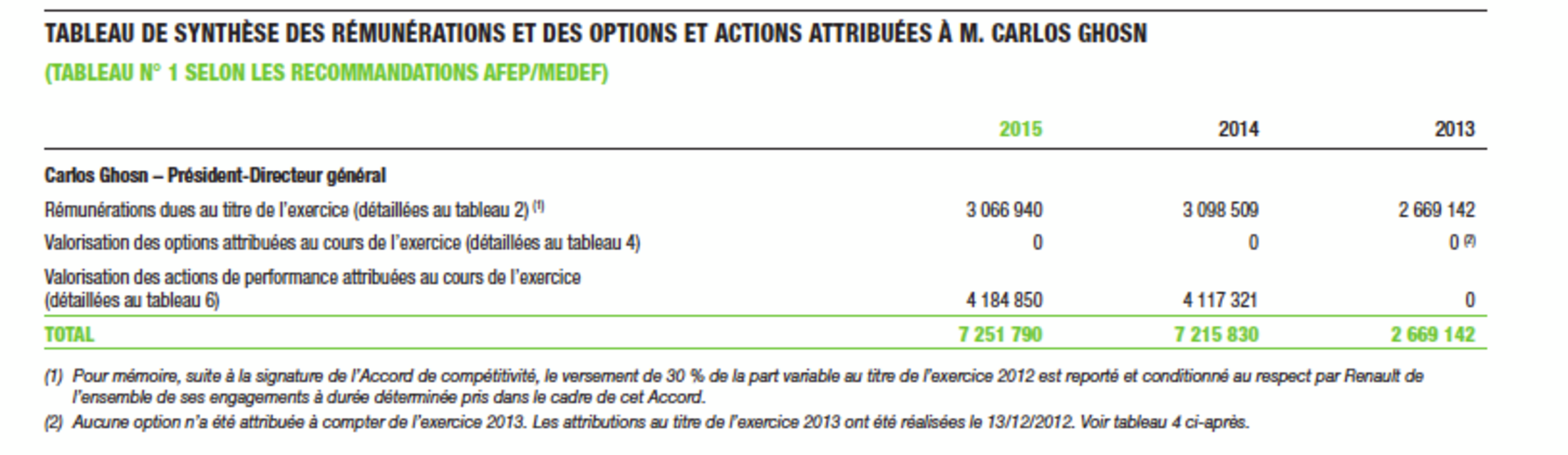

The Renault board, closely guided by its chief executive, was dismissive in its reaction to a shareholders’ revolt last week over Ghosn’s latest pay package. At the annual meeting on April 29th, investors representing 54% of voting rights dissaproved the 7.251 million-euro in pay and bonuses handed to the Renault boss last year, a sum that comes on top of around 8 million euros he received as head of Japanese carmaker Nissan, which is tied in a corporate alliance with Renault.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It was the first time in France that shareholders of a company had made such a stand since the law was changed to allow them a consultative opinion on the remuneration of bosses of companies they invest in. But the Renault board was apparently far from impressed. “It is not for shareholders to pronounce themselves on the remuneration of their executives,” it said. Who then?

At first glance, this outright rejection of the shareholders’ opposition seems to be addressed to the French company’s principal shareholder, namely the State. For Ghosn’s allies, the vote was but the latest episode in a long-running conflict between the Renault board and the government. For years, Ghosn has continuously complained about the behaviour of this unwelcome shareholder, challenging its legitimacy and seeking every possible means of escaping its control, to the point of devitalizing the carmaking group. For Ghosn, the shareholders’ resolution was but the latest attack on him by the State which, with 23.4% of voting rights, clearly tipped the balance of the rebellion.

But while the French government has fired another shot across Ghosn’s bows, the opposition towards him is larger still. For several years, shareholder advisory firm Proxinvest, mandated by Renault investors, has contested Ghosn’s management at the helm of both Renault and Nissan, and called into question the opacity of his pay packages.

It was not until 2011 that it was publicly revealed that Ghosn received between 7 million and 10 million euros in an annual pay deal with Nissan, making him the highest-paid chief executive in Japan. With a combined remuneration from Renault and Nissan this year of 15 million euros he is among the highest-paid corporate bosses in the world.

Last year already, the French carmaker’s shareholders were divided over the almost tripling of Ghosn’s pay package with Renault, which leapt from 2.7 million euros to 7.2 million euros. The move was approved by 64% of investors, the lowest pay approval rating by shareholders within any company listed on the French CAC 40 stock market index.

In the run-up to the annual general meeting of shareholders on April 29th, Proxinvest, representing those shareholders unhappy with the situation, again called for a vote against Ghosn’s pay deal. "As a shareholder, you delegate [power ] to the board,” Ghosn retorted. "It is it which judges, not on the basis of a whim but which weighs up whether the manner in which the CEO is paid is in compliance with his efforts, with his talent, with the situation. It does so in a completely transparent manner.”

This is no doubt yet another example of the independence of the board, illustrated in the makeup of Renault’s remuneration committee, as caricatured as any from companies listed on the CAC 40. The committee members include: Thierry Desmarest, former CEO of oil giant Total; Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière, founder and head of financial services, property, and service industry investment firm FIMALAC; Jean-Pierre Garnier, a former chief executive of pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline; Alain Belda, a former CEO of aluminium-producing multinational Alcoa; Éric Personne, an employee-elected director of Renault, and Patrick Thomas, a former CEO of luxury goods firm Hermès who presides over the committee.

These are men who know the true conditions of leading a multinational company, and the demands of globalisation. They are not of those who have social preoccupations, nor others who have dared to highlight the efforts made by Renault’s workforce such as accepting the slashing of 8,000 posts, agreeing increased working hours and a three-year wage capping, all in order to preserve the group’s production in France.

To justify Ghosn’s outsized pay deal, the Renault board has underlined the group’s “exceptional results”, which include a record turnover of 45 billion euros, net profits of 2.8 billion euros, an operating margin of 5.1%, and a cost-saving plan that is ahead of forecast results.

These indicators are apparently sufficient for the remuneration committee to justify the Renault CEO’s exorbitant pay package. But the board do not seem to be particularly alarmed at Renault’s constantly diminishing industrial activity in France. The group now produces fewer vehicles in the country than it did in 1963, and its agreements signed with Daimler, owner of Mercedes-Benz, which allow for a massive transfer of production and technology to the German firm threaten to weaken it further.

Nor, it seems, is the board concerned about Renault’s lagging behind rivals in the development of electric and hybrid vehicles, or its slow-lane international development which has seen it arrive on the Chinese market at the very moment that this is spluttering.

Shareholders' revolts are gathering ground

What has been the board’s view of the AvtoVAZ adventure in Russia? As well-informed sources have warned for some while, the alliance between Renault and the former producer of Lada vehicles, an alliance which was conceived in such a manner that Renault runs all the risks and Nissan holds every advantage, is turning into a fiasco. Car sales are tumbling in Russia because of the economic recession, and Renault has already been forced into reducing the value of its participation in AvtoVAZ which will account for 1 billion euros of losses in this year’s exercise.

As a result, Carlos Ghosn has announced that he will step down as chairman of AvtoVAZ on June 23rd, when he will be replaced by Sergei Skvortsov, a senior executive with state-owned Russian investment organisation Rostec, Renault-Nissan’s partner in AvtoVAZ. For Ghosn, this will be a manner of keeping at a safe distance in case of any future financial woes. Just as he managed to sidestep involvement in the 2011 so-called ‘spy scandal’, when three senior managers were wrongfully dismissed after they were falsely accused of selling company secrets.

The relative impunity that Ghosn benefits from remains a mystery. For a long while, that impunity was total, at a time when he presented himself as an indispensable key figure in the alliance between Renault and Nissan, playing one group off against the other. It is time that the shareholders of each company start talking to one another, when they might well discover that they have common interests that are not summed up by one man.

The rebellion by Renault shareholders on April 29th is likely to have repercussions beyond the French carmaker. The board’s cynical and curt dismissal of the disapproval of Ghosn’s pay package strips bare a reality that the French employers’ federation, the MEDEF, and the association of large French companies, the AFEP, have for years attempted to cover up with their different advisory codes of good behaviour and calls for corporate good governance. Behind this illusion, and despite occasional pledges, there is no moderation required of business leaders. Neither the financial and economic crisis, nor failures in corporate performance, apparently justify capping the exponential growth of their remunerations. Last year, the average rise in the salaries of the heads of companies listed on the CAC 40 rose by 4% to 2.34 million euros, an average sum that does not take into account various bonuses paid on top.

The process of enrichment has, over the years, been constantly perfected. Stock options are becoming obsolescent, officially because the system came in for so much public criticism, but in reality because it posed a slight risk for business leaders. For stock options lose their attraction if the share price falls below the original value. Now bosses are awarded “performance shares”, which are totally free and guarantee gains whatever happens. Apart from his fixed and variable remunerations, Carlos Ghosn also receives performance shares worth 4.18 million euros.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The attitude of the Renault board is consistent – it has no interest in the opinion of its shareholders, whether that be the chief executive’s pay package or any other issue. At the company’s annual general meeting, a resolution stipulating that the shareholders of Renault be barred from any right of scrutiny concerning Nissan – in which Renault has a 44% stake – was adopted, in effect giving them no opportunity to take position on the management of the French carmaker’s principal subsidiary.

As extremist as it is, the behaviour of Renault reflects the approach of multinationals in general, which haughtily pronounce that they are accountable to nothing and no-one. A major split is in the process of separating company bosses from their shareholders.

Yet the neoliberal trend that began in the corporate world in the 1980s was built on the relationship between the two. Claiming their proprietorial right to be the primary beneficiaries of the wealth created by companies, shareholders imposed an iron management that required ever-higher returns on their investment, totally disconnected to economic reality, creating increasing pressure on company employees.

This wide shift in approach was only possible thanks to the agreement of company executives. Whereas from the end of World War II and until then, bosses regarded themselves as coming from the world of salaried staff, sharing the same goals, they subsequently gave in to the siren calls of shareholders who argued for an alignment of their interests with those of company heads.

The union was made possible by hitherto unthinkable remuneration packages for chief executives, which among multinational companies now represent on average 200 times the average salary of employees. That compares to up to 20 times the average salary during the 1970s.

Today, the revolt against these indecent remuneration packages – once limited to outbursts of public opinion – is gathering ground among shareholders. In Britain, a number of so-called “fat cat” bosses, notably those of BP and HSBC, have faced heated debate over the issue at general meetings. While the groups they preside over show mediocre, even disastrous, results, they have continued to be given giddy pay rises. The alignment of interests between shareholders and chief executives is dissipating, and the heads of multinational corporations, facing the loss of this protective justification for their vast earnings, are now in danger of being revealed for what they are: a caste of oligarchs that are simply unbearable in a democratic system.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse