An opinion poll published this Sunday in France by 'Le Parisien-Aujourd'hui en France' placed far-Right National Front leader Marine Le Pen ahead of rival candidates in next year's presidential election first round vote, including incumbent Nicolas Sarkozy, but excluding the so-far non-declared potential Socialist Party candidate Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Here,Laurent Mauduit argues that the resurgence of the National Front is in large part due to the failure of the French mainstream opposition Left to recognise and address the causes of a deep social malaise in the country.

-------------------------

The small town of Nilvange, situated in the Lorraine region of eastern France, close to the border with Germany, lies at the heart of an area that was once a stronghold of France's bustling steel industry. Today, it is an area of industrial ruin.

This urban community with a dwindling population of just more than 5,000 was recently the backdrop to an event that briefly made national news headlines, but might all too mistakenly be dismissed as a curious one-off. It was the defection to the far-Right Front National (FN) party of a local leader of the Confederation Générale du Travail (CGT), the major French trade union confederation which has long been affiliated to the French Communist Party.

But the event offers a stark warning for the French Left, ahead of presidential elections little more than a year away. For while the defection is a worrisome symptom of the social despair spreading throughout France under the effects of French President Nicolas Sarkozy's social and economic policies, and the chaos into which they have plunged the ruling Right, the resulting popular anger is aimed just as much against the parties on the Left. The latter are no longer perceived as offering a platform to fight back injustice, but rather as making up the cogs in the wheel of an unfair system.

The affair in Nilvange centres on Fabien Engleman, chair of the local branch of the CGT Public Service Workers' union. He began his political life as an activist with the French Trotskyist party, Lutte Ouvrière (Workers' Struggle), before joining the recently created (2009) far-Left, Trotskyist-rooted NPA, (Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste). Then came his recent announcement that he had joined the far-Right FN.

CGT union leaders of the umbrella Moselle section immediately moved to contain the affair. They issued a press release in which, referring to Engleman, it said: "In an interview published on the internet, in which he boasts about being a member of the CGT, he defended: the FN policy of national preference; the idea that immigration is the cause of unemployment and spoke against the regularisation of illegal workers. For our organisations, this situation is intolerable for two reasons. First because a CGT activist has thus promoted ideas that run counter to the fundamental values of our organisation and secondly because his action is an attempt to use the CGT for political ends."

At a February 15th meeting called by CGT leaders of the wider local Moselle département (county) and other local union leaders, "26 members of the Nilvange union branch refused, by a majority vote, to disavow their chair. As a consequence, and after discussions with [Moselle département union leaders], the executive committee of the CGT Federation of Public Service Workers, meeting on February 16th, decided," based on union statutes, "to immediately suspend the Nilvange affiliate from the Federation", the press release continued.

The same warning came in 2002

The defection is worthy of interest for at least two reasons. First, because it occurred in the heart of France's veteran steel-producing region, the Fensch Valley, in what was once a bastion of activism for workers' rights, whose history shares common roots with the national development of workers' rights movements. But, as in many other working-class strong-holds, the Front National has prospered here over the past few years. The region has been hit by a vast number of lay-offs, and a vast amount of misery. In the past, the elected Left has failed expectations, often even giving the impression that it was responsible for the industrial decay. That, in turn, spurred a protest vote, with the FN as prime beneficiary.

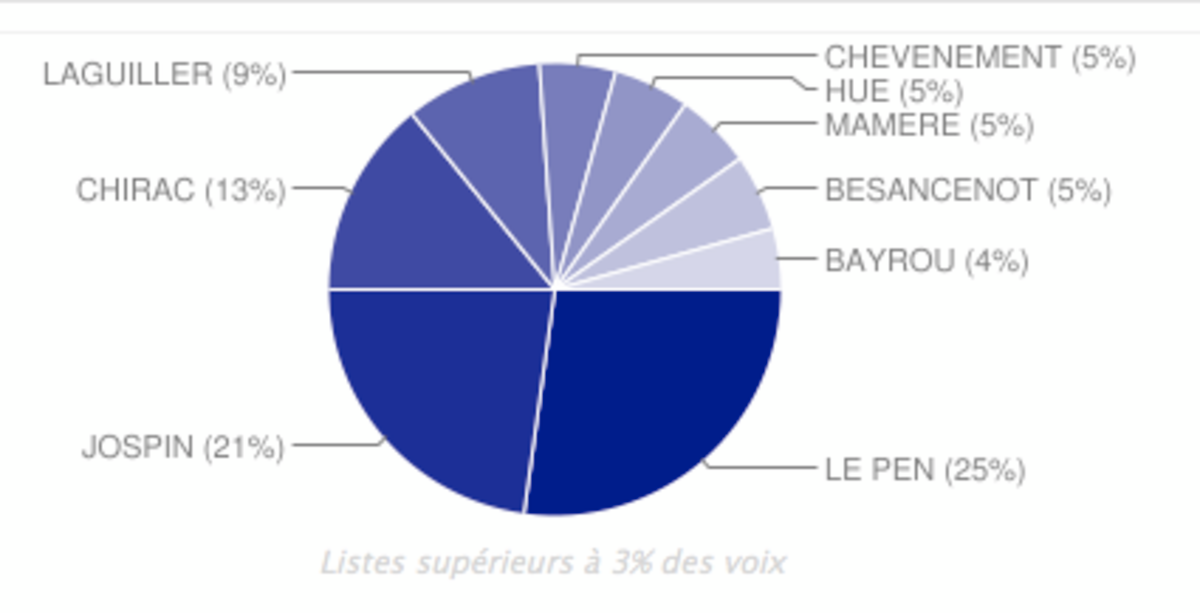

Candidate scores in first-round voting in Nilvange in the 2002 presidential election (click screen to enlarge).

In the 2002 presidential election, the polling in Nilvange produced a result that would have been unthinkable in the past. With 587 ballots or 24.92% of the vote, FN leader Jean-Marie Le Pen took an unexpected first-round lead (for detailed results click here).

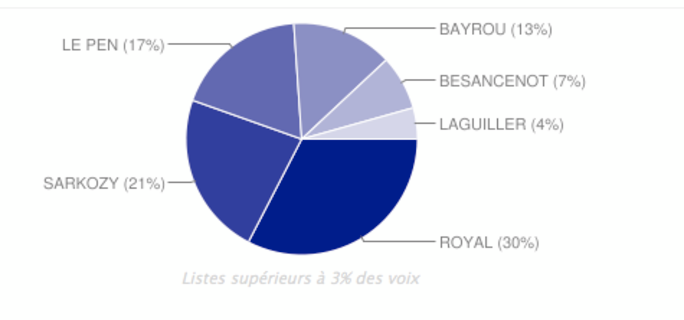

Candidate scores in first-round voting in Nilvange in the 2007 presidential election (click screen to enlarge).

The first round of the 2007 presidential election was held under slightly different conditions. Adopting immigration and security issues often exploited by the far-Right, Nicolas Sarkozy siphoned off a part of the FN's electorate. Nonetheless, in Nilvange, with 489 votes, Jean-Marie Le Pen came in third with a significant 16.65% of the vote cast (for detailed results click here).

The defection of Fabien Engleman to the FN, therefore, is hardly an anecdotal news item, even if he has followed a somewhat bizarre political path; Engleman has professed a love of animals, and is a self-avowed admirer of former French movie star Brigitte Bardot, an animal rights activist and the wife of a prominent FN member. Nonetheless, his meandering political allegiances reflect those of Nilvange and, beyond that, of a larger number of working-class communities in the north-eastern Lorraine region.

The Nilvange incident sets off alarm bells that should not be ignored in the way that the 2002 presidential campaign was, for they are just the same as those ringing before the Left's debacle in April 2002.

Back in 1997, after their surprise victory in legislative elections, the Socialist Party finally implemented several policies that were clearly anchored in the ideals of the Left. But in a number of other domains, they pursued conservative, free-market social and economic policies. These included continued privatisations of both public services and of revenue-producing state-run businesses, a lower tax rate for the highest incomes (and stock option beneficiaries). They increased work flexibility and wage-freezing policies conceded during negotiations on the 35-hour work week. For the disadvantaged sections of society, carrying the weight of these policies was an injustice.

No faith in mainstream Left or Right

Throughout the presidential campaign of 2002, the Socialist Party, cut off for too long from its working class base, primarily courted the relatively affluent middle class. After the euphoria and creature comforts of five years in power came the inglorious elimination of the Socialist Party candidate Lionel Jospin, as of the first round of vote, while the leader of the FN went on to the final, second round ballot against incumbent Jacques Chirac.

The defeat forced socialist leaders to recognise that France remained composed of 7 million blue-collar workers and over 8 million low-wage service and white-collar employees. They have evolved over three decades, but they remain the country's social core. They carry the brunt of the effects of wage freezes, of layoff plans and of de-regulation of the work place.

In 2002, FN leader Jean-Marie Le Pen reached the second round of the presidential election thanks to an overall dissatisfaction of the electorate - including that of the Left- in areas that are historically bastions of the Socialist or Communist Parties. In the industrial Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, another historical site of working class rights' movements, Le Pen took the lead, for the first time ever, with 19.03% of the vote, a nose ahead of both front-runners, Chirac (17.29%) and Jospin (17.06%). The Communist Party candidate, Robert Hue, scored a mere 5.06%.

In the Lorraine region as a whole, Le Pen took the lead with 21.24% of the vote and here again, Jospin came third with only 14.93% of the votes. Hue almost fell off the radar screen with a just 2.6%. According to a series of sociological studies, the election confirmed and re-enforced the FN's title of top political party among the working class population. Generally, Le Pen scores best in the east, north and south-western parts of France, all traditional industrial regions.

CGT Moselle leader, Denis Pesce, in an interview published in French daily Le Monde on February 22nd, admitted the depth of the problem highlighted by Engleman. "When ideas such as those are spread using our own internal structure, it's possibly because we've also missed something," he said. He was "particularly worried" by the extent of sympathy for the FN's policies in the working environment he daily rubs shoulders with. "We hear a lot of facile views about immigrants, how the Left and the Right are all rotten," he added. "People are fed up with Sarko [Sarkozy] and no credible alternative on the Left. As a result, I hear staff say ‘you have to vote FN."

Fuelling xenophobia

The despair now is the same as in 2002, and the anger is tapped from the same source. With 2.7 million unemployed1, (4.6 million if all categories are included), unemployment is undermining blue-collar communities in many areas, and especially those economically devastated wastelands like the area surrounding Nilvange.

Nationwide, poverty has reached record levels and now affects over 8 million people. Low wages have created a working poor that barely earn enough to survive. Out of 23.5 million salaried workers in France, a fifth earn the minimum wage (nine euros per hour or 1,365 euros per month for a full-time, 35-hour working week) or less. One half of all French employees have a monthly income of less than 1,580 euros.

It's not that surprising that the working class has turned its anger on Nicolas Sarkozy, as the CGT's Denis Pesce suggests. A series of corruption scandals, including the Karachi affair, the L'Oréal-Bettencourt affair and the Wildenstein case, and the fiasco of two ministers over the Tunisian crisis, have exposed the worst face of politics, playing into the hands of the FN's mantra that all (other) politicians "are rotten".

By introducing a debate on 'national identity', the campaign against the Roma, or more recently the debate on Islam launched by his ruling conservative UMP party, Sarkozy has borrowed a page from the FN's handbook. Like the FN, he presents foreigners as responsible for the social crisis, thus fuelling a climate of xenophobia.

Since 2002, the Left has done little to win back the working class electorate whose interests it purports to uphold but which it has too often ignored. Even if ever the Socialist Party was to offer, in the presidential elections in 2012, a plan for social progress and a change in the rules of capitalism which, each day, become increasingly favourable to capital to the cost of wage-earners, who could lead it with credibility? The current opinion poll favourite to become Socialist Party candidate is International Monetary Fund managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the economist who has made a speciality of overseeing austerity policies, including the one that is now suffocating Greece. The chances appear poor that the Left will read, much less heed, the subtext of the news from Nilvange.

-------------------------

1: French official statistics use the International Labour Organisation definition which excludes from the term 'unemployed' anyone who has worked, however short or temporary the period, during one month.

English version: Patricia Brett

(Edited by Graham Tearse)