Every article about the predictive algorithms used by the French gendarmerie mentions the Steven Spielberg film Minority Report, which is itself based on a science fiction short story by Philip K. Dick. This comparison is far removed from the reality – as many gendarmes have agreed when interviewed – but it has the advantage of making the gendarmes look modern and operating at the frontiers of science fiction. Even in official documents, in particular during a recent presentation by police about public safety, the new software is held up as a sign of the “gendarmerie of the future” (see below).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Officially known as “decisional analysis”, this new tool has this year been installed in all computers and tablets used by gendarmes. It is in the form of a browsable map of the zones patrolled by gendarmes, which are largely rural areas of France. This map pulls together the history of recorded burglaries and car theft and states the likely risk of these crimes occurring again. These particular offences have been chosen by the team who developed the tool because they make up a third of all crime in areas patrolled by gendarmes, and they are crimes which are quite often reported.

In a note sent to the gendarme's ruling body the Direction Générale de la Gendarmerie Nationale (DGGN), which Mediapart has obtained a copy of, the team developing the project, the Service Central de Renseignement Criminel (SCRC), say that the new tool provides “elements of information on offences liable to be committed in their areas. That allows them to bring in preventative measures and optimise the commitment of their resources”. The tool has been developed in-house, partly to retain ownership of the code and the data, and partly to keep down costs. It was trialled in 2018 by gendarmes in eleven départements or counties across France.

The report sent to the DGGN is an analysis of the results, and it claims these were a success in two respects. First, it is claimed to have been a success in relation to predictions. “On average 83% of burglaries were predicted within an average distance of 2.24km; the distance is 3.15km for car-related offences,” says the report. Secondly, it claims progress in tackling crime. “In comparison with 2017, in 2018 the average fall in the number of burglaries was -8.85% in the 11 départements whereas it was -7.78% on a national level,” it states.

This second figure is regularly referred to by Laurent Collorig, the gendarme colonel in charge of intelligence at the SCRC, in various media appearances. Speaking to France Culture radio, he delighted over the fact that “in these eleven départements, during the first months of the year, the drop in crime in relation to burglaries and vehicle crime was greater than the drop in crime across the whole of France in the gendarmerie's zones”. He said the same thing a few months later on CNews, on France 2 television and on France Inter radio.

The gendarmerie's director general, General Richard Lizurey, made similar claims when speaking to Members of Parliament at the National Assembly in October 2018. “At the end of an experiment carried out in eleven départements for a year, we noticed that the results obtained in the [eleven] départements in relation to burglaries were better than in all the others.”

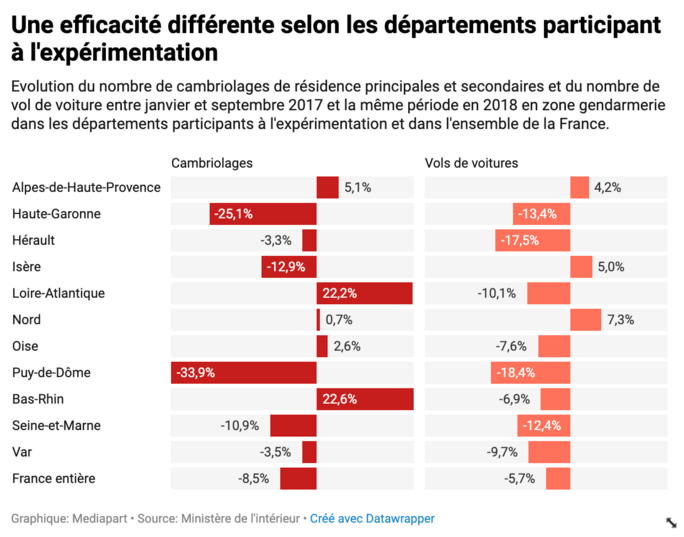

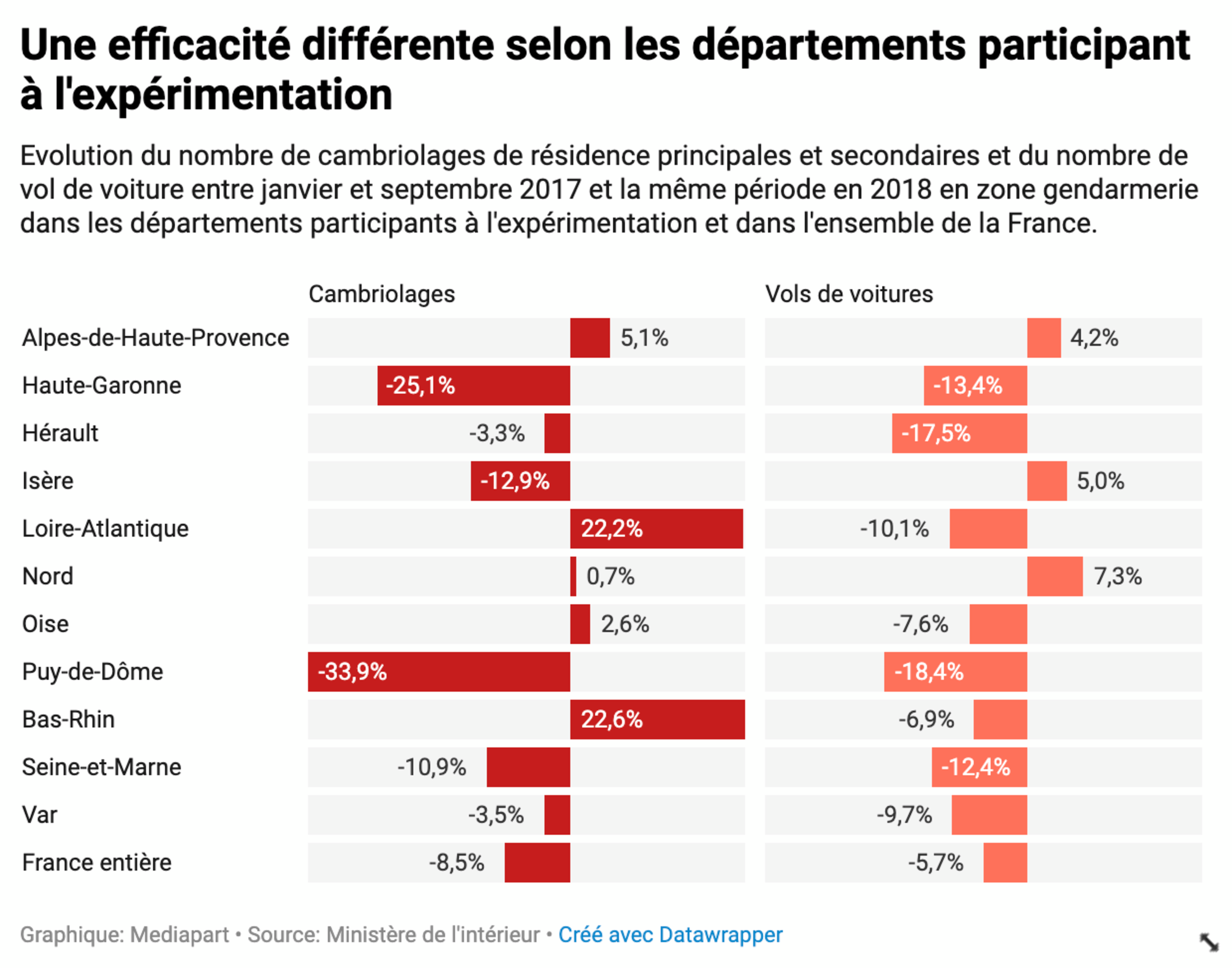

But the gendarmerie's own figures put these claims into perspective. According to Mediapart's calculations which are based on the recorded crime data put online, the number of burglaries recorded in gendarme-patrolled zones across France fell by 8.5% between January and October 2018 compared with the same period in 2017. In the eleven départements in the trial the fall in crime was however lower in this period at 6.8%. How can this difference with the gendarme's own claims be explained? Was the period chosen by the gendarmes to justify the measure cherry-picked to obtain the right results? Or was the analysis carried out on a certain type of burglary? The gendarmerie did not respond to Mediapart's questions on the issue.

Looking at the figures in more detail, it becomes clear that the differences in the figures between all the départements that took part in the trial were very wide. In the Puy-de-Dome in central France, for example, the number of burglaries in the period fell by 33.95%, while in the Loire-Atlantique in western France the figures rose by 22.22%. There are also differences in relation to car thefts.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

To calculate how accurate the tool is, the idea is to compare the crime area predicted by the machine with the places where crimes actually took place. The result indicates that 83% of the burglaries took place on average within 2.24 km of the predicted area. The figure is 3.15km for car thefts. Nonetheless that represents surface areas of 15.7km2 to 31.2km2 in which the crimes were predicted to occur, a large area for gendarmes to cover.

In areas where the gendarmerie is in charge of policing, 65% of the village or communes are less than 15km2 in area, and 24% are between 15km2 and 30km2 in size. When the figures are adjusted this means that the algorithmic tool is able to say that in 83% of cases, there is a risk of a burglary taking place in a given commune.

Measuring the effectiveness of the algorithm is certainly complex. To show its impact – ensuring all other factors are equal – would require a rigorous trial. In this trial, however, the aim was not really to have a perfectly scientific experiment. No specific instructions were given to the software's users during the trial and there was no obligation to use the tool either.

During a discussion at the National Institute for Advanced Studies in Security and Justice (Institut National des Hautes Etudes de Sécurité et de Justice or INHESJ), the gendarme colonel Laurent Collorig referred to two different uses made of the software during the trial. The first was to “organise the [policing] service in relation to the software, in other words put people on the red markers” with the aim of reducing the level of crime in the targeted zone. Other gendarme forces, meanwhile, used the software “for prevention”; for example going to the mayor of a village or town where crime was predicted, to warn them what they could expect in the coming days.

When he addressed Members of Parliament, gendarme boss Richard Lizurey stated: “The local commander can organiser their patrols by concentrating personnel where they are most useful. The gendarme squads thus have at their disposal a predictive tool which helps them plan the way their service operates - without obviously being obliged to follow the guidance suggested by the machine.”

Often the online map is a digital mirror of what the gendarmes themselves observe on the ground. In April 2019 Camille Gosselin, a researcher at the urban development institute the urban development institute the Institut Paris Région, published a report on predictive policing. Writing about the gendarmes' new software tool following interviews with some of its operators she stated: “The analyses that it offers do not seem so complementary to those carried out on a daily basis by gendarmes. Basically it would indicate some areas which are already under surveillance by the security forces or known to the [police] services.”

But data scientist Florian Gauther, who when he was at the French state's body in charge of modernisation ETALAB worked on a tool called PredVol which is similar to the gendarmes' algorithmic software, said that even this showed the new tool's usefulness. His conversations with the software's users showed that “what works is showing the history of the facts dynamically on a map”. In other words, it would be a digital version of a standard operational map with drawing pins in it that officers could have in their hands while out on duty.

The algorithm is, though, just one tool working towards an overall strategy. The strategy in this case involves preventative patrols to prevent crimes being committed or to move criminals on. Interviewed in a report on France 2 television on the algorithmic approach, a police officer on the streets in the département of Seine-et-Marne east of Paris said he was pleased that, thanks to the new software, they had “pushed criminals to other areas”. The consequence of this approach, however, would simply be to displace crime and improve one force's figures at the expense of those of another.

A final point is that however efficient the algorithmic analysis might be, it needs to be supplied with the most reliable and exhaustive data available. Researcher Camille Gosselin highlights a problem with the data that was used for the system in the recent trial. “The data which is fed into the decisional analysis platform comes from facts which are reported and brought to the knowledge of the [police] services,” she said. “As always, these statistics raise the thorny issue of bias: first and foremost they reflect police activity, and don't take into account the victims who don't make a complaint.”

The risk here is that the zones that are already neglected by gendarmes – where people do not report burglaries and the theft of cars – will become even more neglected by officers who are too focussed on their interactive maps.

Meanwhile the software is now in use on all tablets and computers used by gendarmes, though the algorithm is still being improved. There are also plans for road safety data to be added to it in the coming months.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter