There is no mistaking the fact that it is climate year in Paris. In December the city will host the much-heralded global meeting of heads of state (the 21st Conference of the Parties, or COP 21), which has the task of forging a new international accord on fighting climate change. But before then captains of industry are to get their say on these subject too. For in an initiative by French ecologist Brice Lalonde, business leaders from around the world have been invited to a Business and Climate Summit at UNESCO headquarters in the French capital in May. The gathering is to bring together over a thousand corporate bosses to crystallise their ideas for cutting CO2 emissions and for new public policies on the climate front.

Lalonde is a former ecology militant who became France's environment minister and is now a UN advisor on sustainable development. He was environment minister under two Socialist governments during the 1990s and was designated France's climate ambassador under Nicolas Sarkozy's centre-right presidency. His current role is with Global Compact, a UN initiative launched in 2000 to develop corporate social and environmental responsibility.

According to Lalonde, the corporate world is in fact prepared to countenance government regulations and environmental constraints to address climate change. “The idea is that companies tell governments what they need to go forward,” he told Mediapart. “They are ready to forge agreements in aerospace, cement, lighting (...) but they need a long-term framework. They know that climate change is there and that they cannot ignore it.”

On the surface so far so good – industrialists actually asking for regulation and environmental constraints. However, in a presentation of the summit made public at the Davos World Economic Forum in January, the language was a lot less compliant and boiled down to a pro-business position dressed up in green clothing. “There is a growing recognition within the business community that a low carbon path can secure economic growth, ensure human development, and protect natural capital,” the presentation said. In addition, one of the planned summit's plenary sessions is entitled 'Integrate climate features into the world economy'. No mention there of changing the economy to safeguard the climate, for instance, or how to prosper without growth.

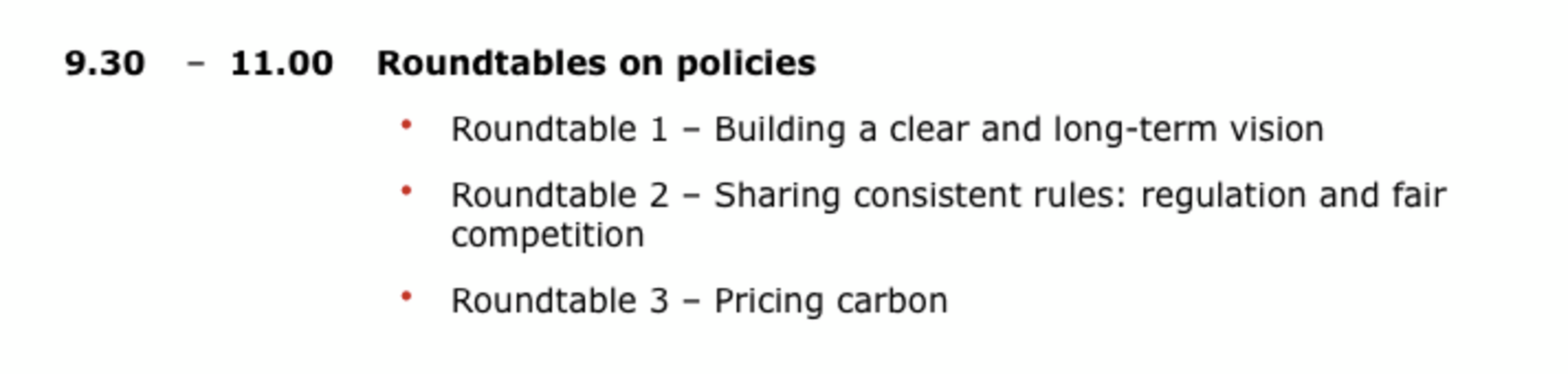

The provisional programme reflects fairly unambitious climate aspirations, such as 'Let’s make low-carbon society desirable', or 'Innovation for a low-carbon world'. Nothing about energy efficiency, or deep decarbonisation, even though this idea is supported by the United Nations. The circular economy and the role of renewables are not mentioned either. Curiously, a previous draft was both more precise and more ambitious, as can be seen in the extract below.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

So it would appear that those crafting the programme for the Business and Climate Summit preferred to leave to one side any issues likely to ruffle feathers in board meetings. For Lalonde, the programme unveiled at Davos is only a draft, but says that, nonetheless, “an impressive number of partners are prepared to go with that”. The idea, he added, is not to “remain within like-minded circles” - in other words within green circles - but to get businesses' messages across massively to political decision-makers and negotiators from all countries in the lead-up to COP 21 in December.

“At every previous COP there was always a business meeting, but it had no influence on the summit and no follow-through was done inside companies between two conferences,” Lalonde said. Hence the idea this time of holding the business summit six months before the diplomatic event itself, to work out a set of climate demands from the corporate sector, which participants will then try to promote to their governments.

As a strategy for winning influence, using the UN label and the climate cause banner may certainly make good sense for business. Last September, UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon brought together leaders from industry and finance to “catalyse climate action” – diplomatic negotiations at previous climate summits having too often failed to live up to expectations.

Business leaders will pay between 10,000 euros and 30,000 euros to speak at plenary or round-table meetings, or both, at May's summit at UNESCO, and the meeting itself will cost some 300,000 euros to stage. Companies in France's stock exchange, the CAC-40 index, are well represented on its steering committee via various business lobby groups, such as the private business organisation AFEP, the business for the environment group Entreprises pour l’environnement (EPE), the employers' federation MEDEF, the group representing industrial firms, the Cercle de l’industrie, the sustainable development group the Conseil mondial du business pour le développement durable (WBCSD), and Global Compact France, where oil company Total, one of the biggest national polluters, has two seats.

But one company is even more prominent than the others – Areva, the French nuclear group, which mines and manufactures nuclear fuel, builds nuclear power stations and stocks and reprocesses radioactive waste. For one of its executives, Myrto Tripathi, is among those deciding the summit's agenda.

Tripathi is what's called 'new builds offer director' for reactors at Areva, with her job essentially being to sell the group's third generation pressurized water reactor. Previously she was sales manager for nuclear fuel in India from 2009 to 2011. Areva continues to pay her salary but, according to Charlotte Frérot, communications director at Global Compact France, “it is as if she were employed by us”. Tripathi does not occupy a strategic position, according to the organisation. “We are not here to represent nuclear interests, but we need all possible energies and abilities,” Frérot said.

Nevertheless, Tripathi is in charge of the Solutions White Paper that is to be published following the summit, and she takes part in choosing speakers for round table discussions. Her name was suggested to Lalonde by Jean-Marc Jancovici, an engineer and recognised specialist in carbon reduction who is president of think tank The Shift Project, one of the summit's organisers.

'I thought it was rather good of Areva to send us someone'

Tripathi confirmed in an email to Mediapart that Areva had seconded her to work at Global Compact France from December 2014 until January 2016, but said she was not involved in selecting which CEOs would speak at the summit. “I was recruited for my knowledge of both the climate issues and the corporate world, and I am proud to be able to contribute concretely to the awareness and mobilisation of all on the climate emergency. Far from reproaching companies for interfering in the debate, on the contrary they should be encouraged to get involved.

“Like other groups, Areva has a policy of seconding some of its experts to external organisations. Their salaries continue to be paid by Areva during the secondment, according to the terms of the agreement negotiated by Global Compact with Areva. Areva does not intervene in any way in the work of its seconded experts during the time of their assignment,” Tripathi said in her email.

Mediapart asked Lalonde if being paid by the main player in the French nuclear industry and being so closely involved in helping organise the business and climate summit could possibly involve a conflict of interest. He seemed not to understand the question, responding: “I thought it rather good of Areva to send us someone.” Global Compact, he said, does not have the resources to pay someone like Tripathi, and “this is a way of contributing to the summit in kind”.

But is it moral to employ an executive from an industry that has a direct interest in the outcome of the conference? Mediapart continued. “Nuclear [power] is carbon-free energy,” Lalonde said, though he added that he could just as easily have asked for the same contribution from Dutch electronics firm Philips, Anglo-Dutch food group Unilever or Franco-Belgian energy group GDF-Suez.

Areva, in financial turmoil over ever-rising costs and repeated delays to its newest reactor, the European Pressurised Reactor (EPR), is very interested in positioning itself in the low carbon market, Mediapart suggested. “I try and deal with nuclear [power] calmly. We are obliged to deal with it. I try and integrate that into my approach, but I do not think I depend on it. There is no conspiracy,” Lalonde replied, adding that Tripathi was “one person out of 30 others. One person paid by Areva has no influence on our summit, I guarantee it”.

Yet Tripathi has tried to offer the nuclear industry a choice position at this strategic summit. In an email sent to colleagues, made available to Mediapart, she says: “I believe it is essential for us to have a representative of nuclear power as a speaker in the 'Energy' round table.” This, she says, is because “nuclear is one of the solutions [available] today without which we will not manage to meet the challenge of climate change (...) Companies do not have the same reticence as the general public or NGOs. If we want to be credible in our wish to speak for them, we cannot ignore nuclear [power] in our approach to the climate debate.” Global Compact declined to divulge the list of participants at the Business Climate Summit, so it is not possible at this stage to know whether Tripathi's request was favourably received.

This is not the first time Global Compact's role has been questioned. Prakash Sethi and Donald Schepers, researchers at City University of New York (CUNY), wrote in a report published last June that the organisation had failed to have a significant impact on corporate social responsibility, had lost credibility with civil society and had become highly dependent on business.

No one can criticise the United Nations for trying to persuade companies to reduce their CO2 emissions. But Global Compact uses a mix of approaches that carries the risk of discrediting its business summit. Although it is officially supposed to promote the commitment of private players to the fight against climate change, there is no guarantee that it will prove to be more than a lever for industrial lobbying. Certain energy producers, food manufacturers or electronics goods makers have a great deal to lose if drastic policies promoting energy efficiency and the preservation of natural resources were to be adopted.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter