“Thirty years after the events, now that emotions have calmed, and also with the hindsight I have regarding my professional life, I thought that this was a chance for me to express both my deepest regrets and my apologies,” said Jean-Luc Kister. “First of all to Fernando Pereira's family, in particular his daughter Marelle, for what I call an accidental death and what they consider to be an assassination. I also wanted to apologise to the members of Greenpeace who were aboard the Rainbow Warrior that night. And then to the people of New Zealand which, it must not be forgotten, is a friendly and ally nation in which we conducted an inappropriate clandestine operation.”

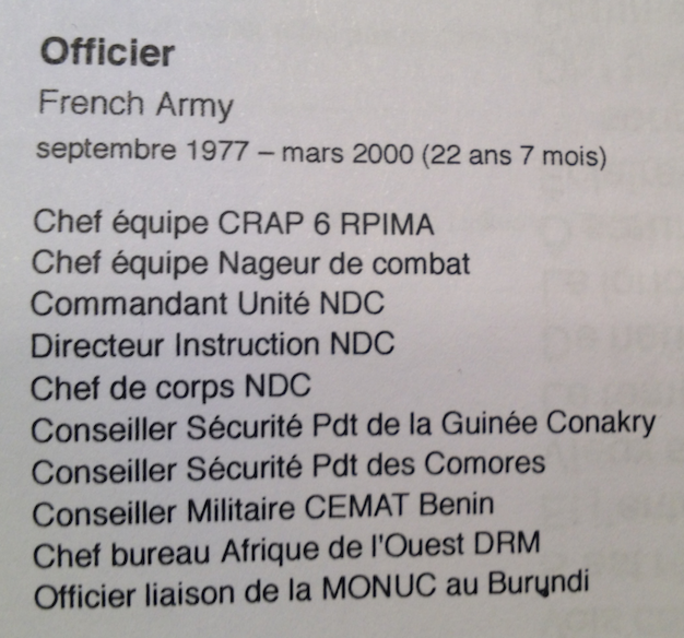

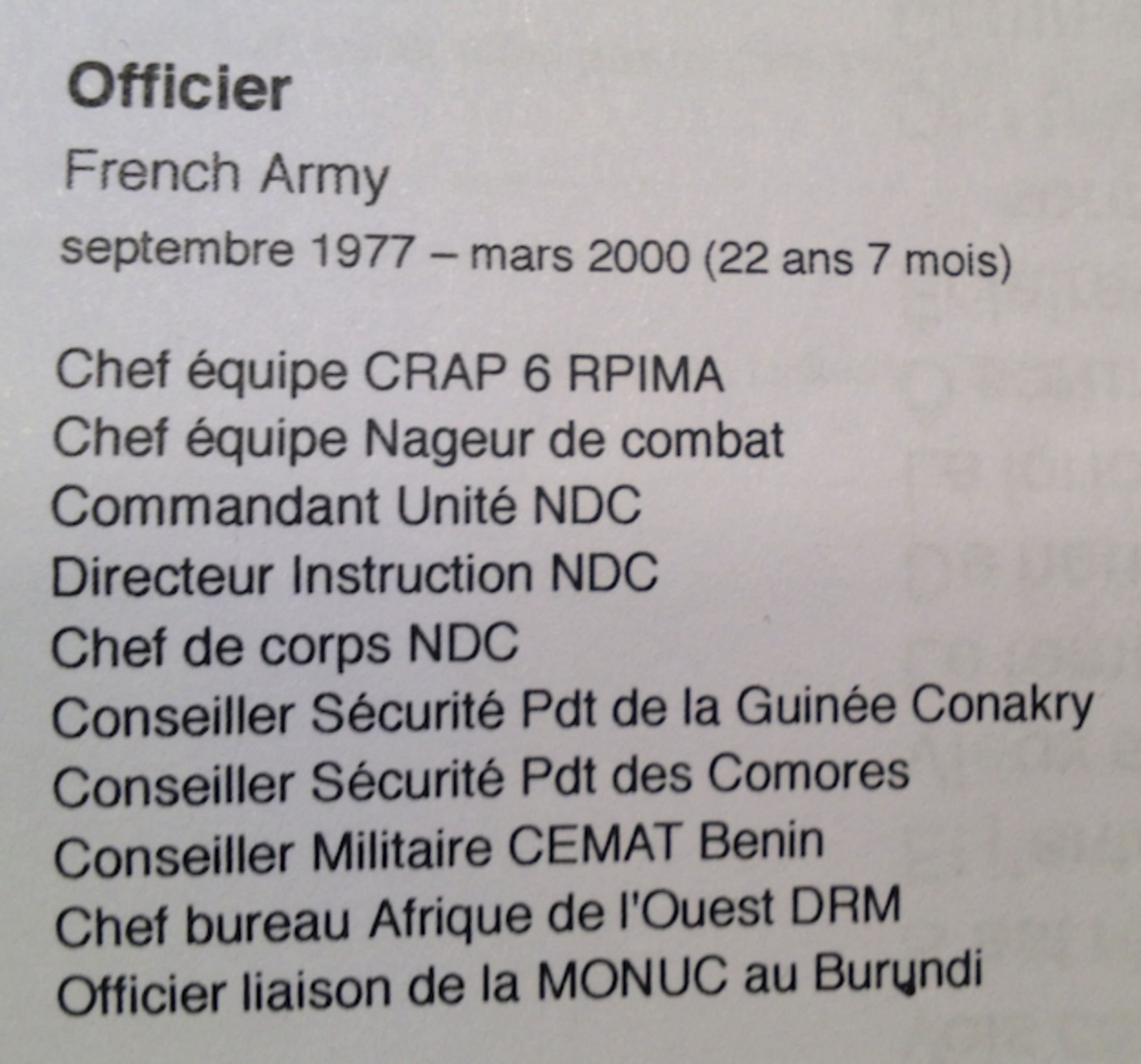

It is an unprecedented event. A secret agent not only decides to emerge from the shadows in which he has always lived, but in particular he does so to offer his apologies to the victims of a clandestine operation which he was ordered to carry out by his government (see video of the interview, available in French only, below). Jean-Luc Kister, now 63, who left the French Army in 2000 with the rank of colonel, was in 1985 a captain and member of the combat frogmen unit of the Service Action of the French foreign intelligence service, the DGSE. At the time the unit was based at Aspretto in Corsica. That was why he was in charge of the team tasked, on the evening of July 10th 1985, with placing two limpet mines on the hull of the Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbour on New Zealand's North Island. The vessel, Greenpeace's flagship, was taking part in protests against French nuclear tests in the Pacific Ocean.

This team of secret agents, the third of three involved, was the final chain in the operation drawn up to carry out what was a political order to sink the Greenpeace boat. The first team had the job of taking all the diving equipment, explosives and detonators to New Zealand, while the second team was there to coordinate the entire operation, taking charge of communications and travel, looking after operational movements and carrying out final reconnaissance.

The first team was on board the yacht Ouvéa, which put back to sea on the eve of the attack having come from the French overseas territory of New Caledonia. The team consisted of a skipper who worked for the DGSE, Dr Xavier Maniguet, and three non-commissioned officers sailing under false identities and who came from the same combat frogmen unit as Jean-Luc Kister. The second team contained the highest-ranking officers directly involved, Majors Louis-Pierre Dillais and Alain Mafart, both also from the DGSE combat frogmen unit, plus another, female secret agent called Captain Dominique Prieur. It was Mafart and Prieur who posed as a Swiss couple Alain and Sophie Turenge and who were subsequently arrested in New Zealand while using their fake identities.

Jean-Luc Kister led the third team which included fellow diver Jean Camas, an adjutant whose alias was 'Camurier'. Their task was to carry out the final stage of the mission – to sink the Rainbow Warrior. This team also contained a third man who was in charge of delivering and then recovering the materials - diving equipment and explosives – that the two divers needed, and to ferry them to and from the diving zone in a Zodiac inflatable boat. This frogman, nicknamed 'Pierre le marin' ('Pierre the Sailor'), was Captain Gérard Royal, one of the brothers of Ségolène Royal who is the current environment minister in the French government.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

If one includes Captain Christine Cabon (alias Frédérique Bonlieu), whose role was to infiltrate Greenpeace at Auckland in the months before the attack, as well as Captain Kister's stand-in, who remains anonymous, and who was on hand in case of some last-minute unforeseen difficulty, the operation on the ground in New Zealand itself involved a minimum of 12 secret agents from France's DGSE. Yet despite the precautions taken to avoid any ‘collateral damage’, as deaths and injuries are euphemistically called, and despite the professionalism of those taking part, as illustrated by Colonel Kister's subsequent career, the operation was a fiasco.

The Rainbow Warrior was indeed sunk, but a man onboard lost his life, the photographer Fernando Pereira, while the global scandal that the attack caused became an affair of state in France as suspicion quickly fell on the French secret services. It rocked François Mitterrand's presidency, forcing the departure of his loyal defence minister, Charles Hernu, and triggering the resignation of the head of the DGSE, Admiral Pierre Lacoste.

The third frogmen team

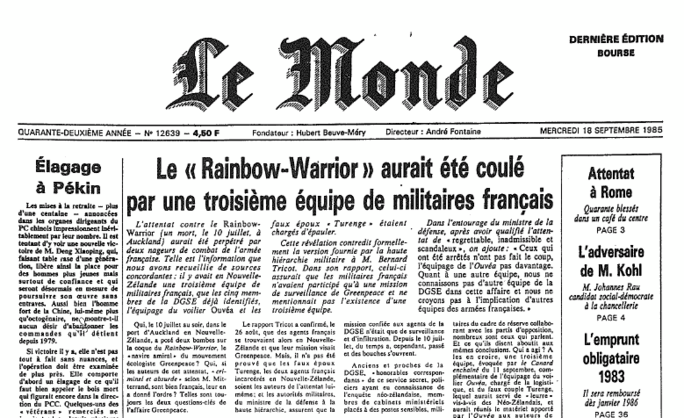

However, the strategy of lie-telling adopted by the French president nearly worked. Were it not for the revelation by Le Monde on September 17th 1985, under my byline and that of Bertrand Le Gendre, of the existence of a third team of frogmen whose task it was to place the two explosive charges, the fake story put about that the DGSE were involved in a simple surveillance mission would have continued to gain ground, with the complicity of those media opposed to investigative journalism.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Moreover, despite the official recognition in September 1985 of French responsibility by the prime minister of the day, Laurent Fabius, who is today foreign minister, various media lackeys for the government and the military hierarchy continued over subsequent years to raise doubts over Le Monde's revelations, to play them down and discredit them. This moment of victory for the truth of news reporting over the lies of government, a symbol of the counterweight of an independent press, was a dangerous precedent for the authorities that they had to bury at all cost, through confusion, or tarnish through rumour.

Thirty years later, Colonel Kister's declarations now silence all those bad losers. By confirming the revelations of 1985, right down to the details disclosed, his words demonstrate the extent to which the existence of the third team was key to the Rainbow Warrior affair and the only evidence that could bring down the whole pack of cards of official lies. The fact remains that this interview granted to Mediapart is an epilogue to the story that I would never have imagined even if, in reality, I did all I could to establish the trust that made it possible, by making a distinction from the start between the primary responsibility of those who gave the political orders and the secondary responsibility of the military who carried them out.

For this meeting was an improbable scenario. For a secret service agent, the obedience to orders that the executive authorities might give him to carry out illegal actions – in this case an act of state terrorism in a friendly and ally nation - rests on a pact of trust. This is the guarantee that his true identity will never be divulged, whatever happens - in short, that his existence will be covered up as if he had never existed. Yet, on his own initiative, Colonel Kister has today chosen to come and explain himself in front of the journalist who symbolises the breach of this pact; the journalist whose revelations on his key role in the attack could, at the time, have put his security in danger.

He has two motivations for doing this. On top of the remorse of a military agent who, in his own words, has “the death of an innocent on his conscience”, there is a desire to defend the honour of his unit in the face of the foolhardiness of the politicians who dragged him into this “inappropriate” operation.

Anyone unfamiliar with this long-ago affair will doubtless be astonished to learn that the secret agents tasked with carrying out this operation had put forward less drastic solutions to fulfil their mission objective, which was to hinder Greenpeace's maritime protest campaign against French underground nuclear tests, which were carried out on the southern Pacific Ocean atoll of Mururoa. This means that the people who gave the teams their orders via the military hierarchy – the government authorities of the day – bear an even greater responsibility for what happened.

Indeed, in his account Colonel Kister describes the surprise of the DGSE agents when they learnt that their objective was a symbol of civil society and, above all, when they understood that the people giving them their orders excluded all other approaches than the attack to neutralise the Rainbow Warrior. It was this decision taken by the political authorities which would lead to the tragedy.

“There was a desire at a high level to say: no, no, it must be stopped for good, a more drastic measure is needed […] We were told: no, it has to be sunk,” Kister told me. “So then … well, for us, it's simple, to sink a boat you have to put a hole in it. And there are some risks there. You point out that there was a risk because you don’t know who might be behind… [...] At all times, and right to the last moment, I have to say that the leaders of the teams always had it in mind to ensure that there would be no collateral damage. And so it was planned in such a way as to get the boat evacuated so there was no one on it, with a certain time delay between the two explosions - that was also done deliberately to ensure no one got back on the boat. In the end it seemed that Fernando, who was a professional and enormously attached to his cameras, went back [on to the boat] and he was trapped at the moment of the second explosion which had to topple the boat. And he drowned to death.”

Ever since those events, when frogman Jean-Luc Kister, with his colleague, placed the explosives on the Rainbow Warrior's hull at night in Auckland harbour three hours before they exploded, he has lived with the memory of that death. This is because it was a death that he had sought to avoid, in choosing two explosions, with the most powerful one first to ensure the boat was evacuated, with the second coming three to four minutes later to finish the job and scupper the vessel. But it is also because Fernando Pereira's death summed up the madness of the mission that had been given to them, a criminal act against a peaceful movement.

'I have the death of an innocent on my conscience'

“Indeed, I accept this responsibility,” said Jean-Luc Kister, after making his apologies and expressing his regrets. “I acted upon orders. And I did my duty, the duty that had been imposed on me by the political authorities.” Then, after I reminded him of our first meeting in 2012, which was at his initiative, and asked him why Pereira's death seemed to haunt him like a ghost, he discarded professional reserve.

“I would not say that it haunts me like a ghost. But nonetheless you have to realise that we are soldiers, that we dedicate our life to the security of our fellow citizens, the country, and that we are not – even if, sometimes, and very rarely, we are given the right to kill – cold-blooded killers. We are not assassins, and we have a conscience. And this conscience … Indeed, with the passage of time, as I said, emotions have become calmer, in my mind too, but my conscience told me nevertheless to make these apologies, to explain, to try to explain because I well understand that, for the victims, it is very difficult to understand my somewhat technical explanations. But what must be understood is that we're not cold-blooded killers.”

As journalists, we are always on a journey. Not just in the prosaic sense of immersing ourselves in ways of life, lands and cultures that are different from what we are used to, but also, and more fundamentally, in the hope that our reports might break down prejudices, shift perceptions and change situations. This meeting with Jean-Luc Kister is an illustration of that: of how journalism can produce this kind of unprecedented gesture, the public apology of a French secret agent on a foreign television station.

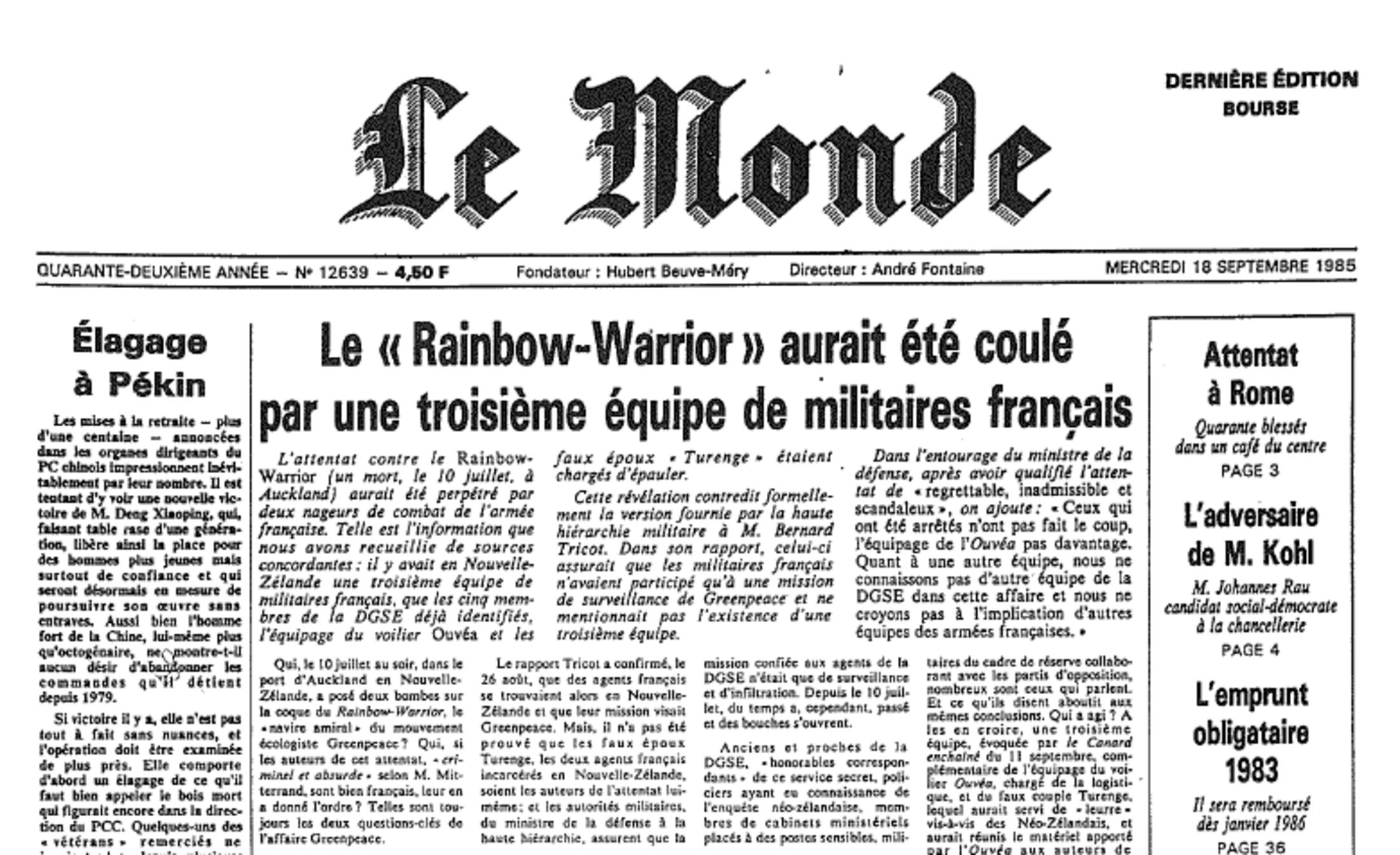

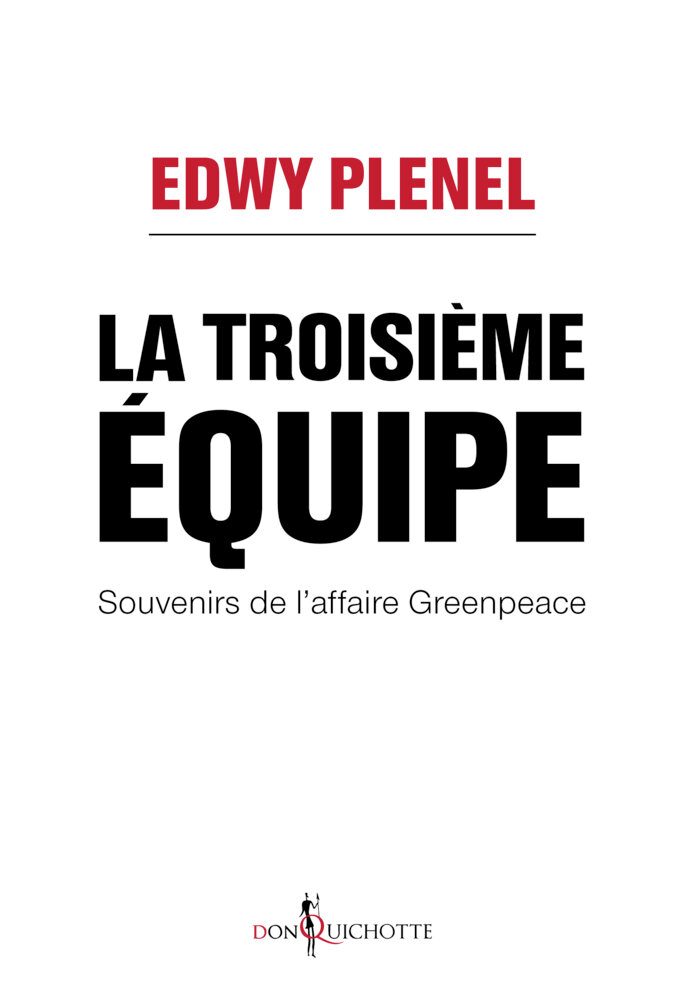

The meeting between the man who sank the Rainbow Warrior and our fellow journalists at Sunday, a current affairs programme on TVNZ, New Zealand's state broadcaster, came about through a book I published in June this year. “I decided to end my silence, somewhat against my own wishes, because your latest book La Troisième Èquipe had rekindled the debate,” Jean-Luc Kister told me. “At the beginning I was quite reticent,” he added. Then, by listening to him closely, one understands that though he is speaking in his own name he is nonetheless expressing a feeling shared by the others who took part in the operation, even by the service to which he belonged and which, perhaps, understands that a line can now finally be drawn under a wretched affair that has long besmirched its reputation.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“I was made to understand that it would be better to speak face to face, that I could express myself rather than others expressing themselves in my place,” said Jean-Luc Kister. “And so I told myself that it was also an opportunity for me, in relation to the people of New Zealand, of Greenpeace, of Fernando Pereira's family, to give my apologies. In a personal capacity, because I am speaking only for myself, but I'm sure that all the participants in the operation have the same feeling as me. Perhaps less strong, because I have the death of an innocent on my conscience and it weighs upon you, that's for sure.”

Acknowledging that he had forewarned at least one of his “colleagues” who is still on active duty, Colonel Kister used the opportunity provided by the publication of La Troisième Èquipe to exercise what he calls a “right of reply”. It was Chris Cooke, Sunday's producer, who started the process rolling last June from Auckland. Informed about the book's publication, Cooke contacted me by email and then had the book translated into English. Following two previous documentaries, one in 2005 (in four parts) and the other in 2010, the Sunday team had been searching in vain for the people who placed the explosives. Cooke was surprised to discover that I had deliberately chosen not to give the identities of the two members of the third team, even though I knew them and had already mentioned them on my blog in January 2013 in the middle of the fight for the truth in the Cahuzac affair.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Replying to him that the choice not to identify them lay at the very heart of what I was saying – a plea on behalf of the participants who were condemned, an indictment against the presidential system that was spared – I told him that Jean-Luc Kister did not hide himself away, as shown by his profile on the professional social network Linkedin (see his profile here, which has since had some details removed, notably his past as a frogman, since the image shown above). That is how they got in touch and how, in turn, Colonel Kister called me on my mobile phone on Monday July 27th.

From our meeting in 2012 to public apology in 2015

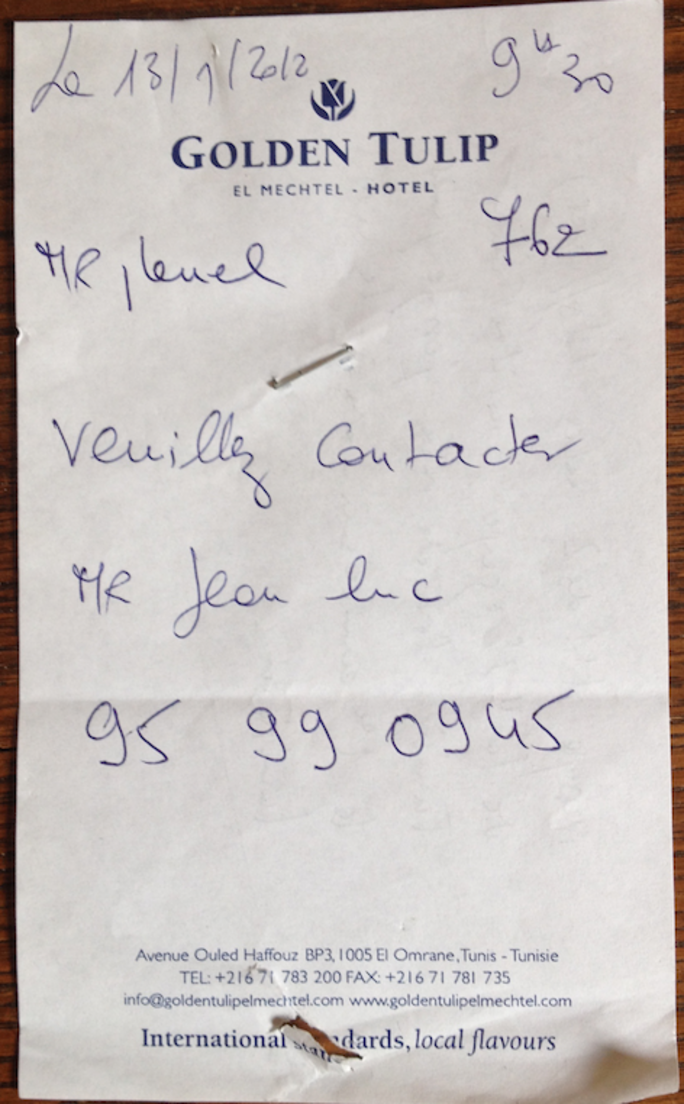

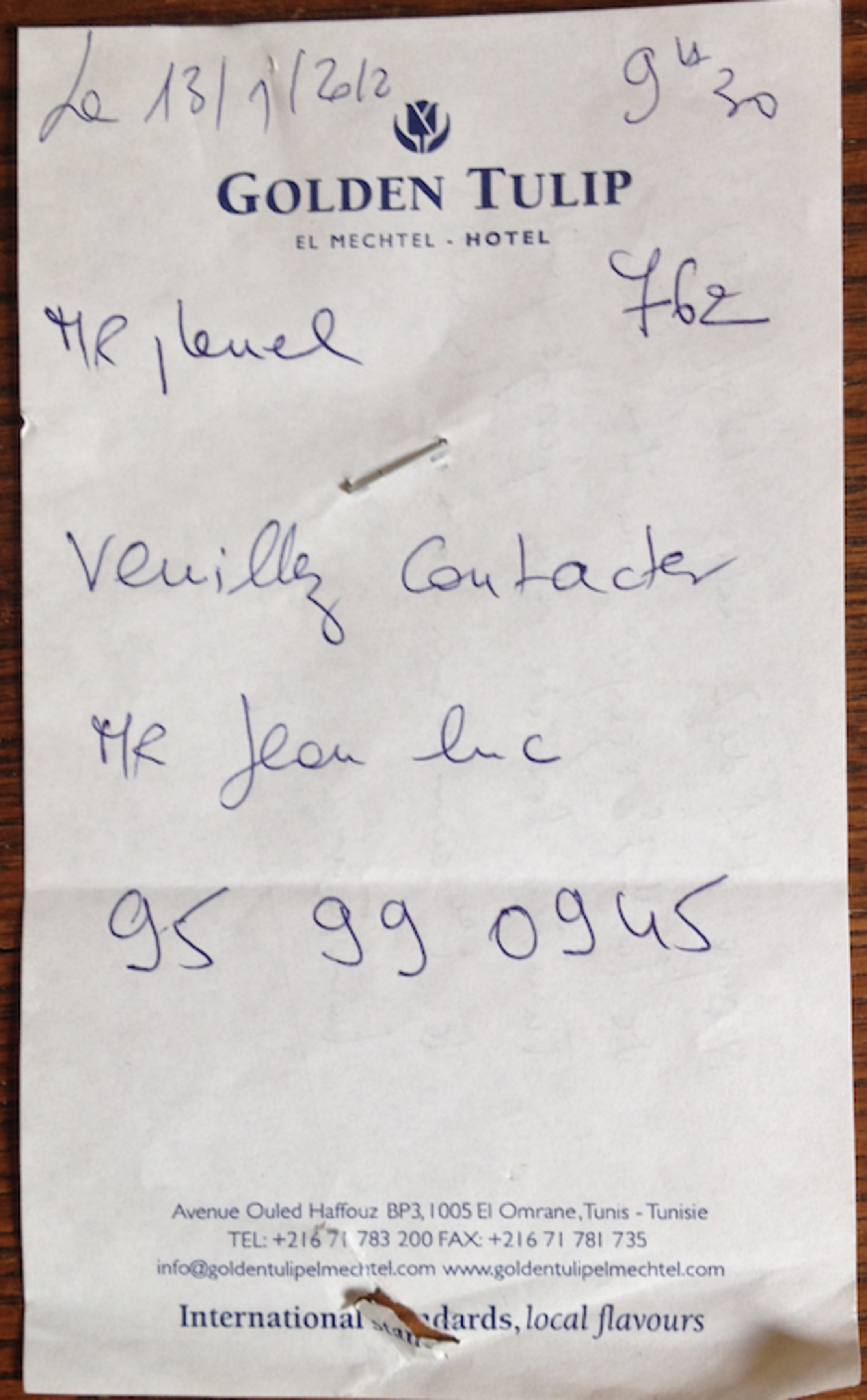

We met the following Thursday, July 30th. It was our second meeting following the one on Friday January 13th 2012, in Tunis, in the middle of post-revolutionary fervour in Tunisia. Colonel Kister was working there for the United Nations security department, the UNDSS, who were his employers from 2000 to 2014 in Iraq, Lebanon, Kurdistan, Burundi and Tunisia. He had just heard me on a local radio station speaking about the freedom of the press and the right to information, which was the purpose of my trip to meet the Tunisian media. When I got back to my hotel I found a note (see below, right) that had been slipped under my door inviting me to call “Mr Jean Luc”, without giving any more details.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

If I have kept the note it is without doubt because it embodies this unexpected connection between two men who, though of the same age, should never have met as they were situated on such opposing sides – state secrecy and the right to know. Jean-Luc Kister wanted a “man to man” explanation: he suspected me of having revealed his identity in 1985, or rather of having thrown him to the wolves. I believe I demonstrated to him that this was not the case at all, and that on the contrary I had defended those involved. In fact, in the columns of Le Monde, where I worked until 2005, we had mentioned “Jean-Luc K” only in August 1986, then “Jean-Luc Kyster” (with an incorrect spelling) only in September 1987. But even though it was done discreetly, we did identify him all the same; this factual detail enabled us to reaffirm the reality of the third team that some people were stubbornly still denying in 1990, notably in French daily Le Figaro.

Colonel Kister is, though, still angry about how his name was leaked to the press: an “act of high treason”, as he puts it, and one for which he blames politicians. “I don't hold anything against journalists. You did your job. For me, it's the political authorities.” He added: “I think that if we had been in the United States other heads would have rolled, for high treason.”

The need to write La Troisième Èquipe was born out of the Tunis meeting, and what I had learnt from it: the frustration of the participants in this outrageous operation – or rather, diabolical, if you go by its code name which was 'Operation Satanic' or 'Operation Satanique' as it was variously written. Deprived of any internal debriefing because of a political ban, those involved in the operation had to bear the weight of it alone while the people in power at the time – in particular President François Mitterrand who was by dint of his position the head of France's armed forces – buried the issue as fast as they could, having never been called to account over it or even having had to give an explanation. So from this book emerged these two interviews, one with Mediapart, the other with Sunday, to be broadcast simultaneously on Sunday September 6th, at opposite ends of the Earth (see boîte noire below).

Colonel Jean-Luc Kister, who is now a self-employed security consultant, is getting ready to depart on other missions on the continent of Africa where he has served a great deal. If there is one act that he claims with pride it is that of having saved the combat frogmen unit which came close to being dissolved after the Rainbow Warrior fiasco. It is now based at Quelern in Brittany, in north-west France, and he was later its commanding officer (see a film here on instructing frogmen commandos made by one of the people he trained). It was during this period, in 1994, that he was made a knight of the Légion d'Honneur in the presence of Bob Maloubier, the legendary founder of the combat frogmen unit at the Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage SDECE, the DGSE's predecessor.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

“You never really leave the secret services,” is the sage assertion on the back cover of Maloubier's book L'espion aux pieds palmés ('The Spy with Webbed Feet') published by Editions du Rocher in 2013. In 2010 Maloubier, whose life story reads like something from a novel, and who started his exploits as a French secret agent for Britain's Special Operations Executive (SOE) in World War 2, played himself in the film Film Socialisme by Jean-Luc Godard. The film-maker later gave Mediapart a long interview about the film (see here). Maloubier's autobiography ends with the story of the filming, which was abruptly interrupted by the news of the death – while flying over a glacier – of the man Maloubier considered his “spiritual son”, Xavier Maniguet, the captain of the Ouvéa. Maloubier himself died on April 20th 2015.

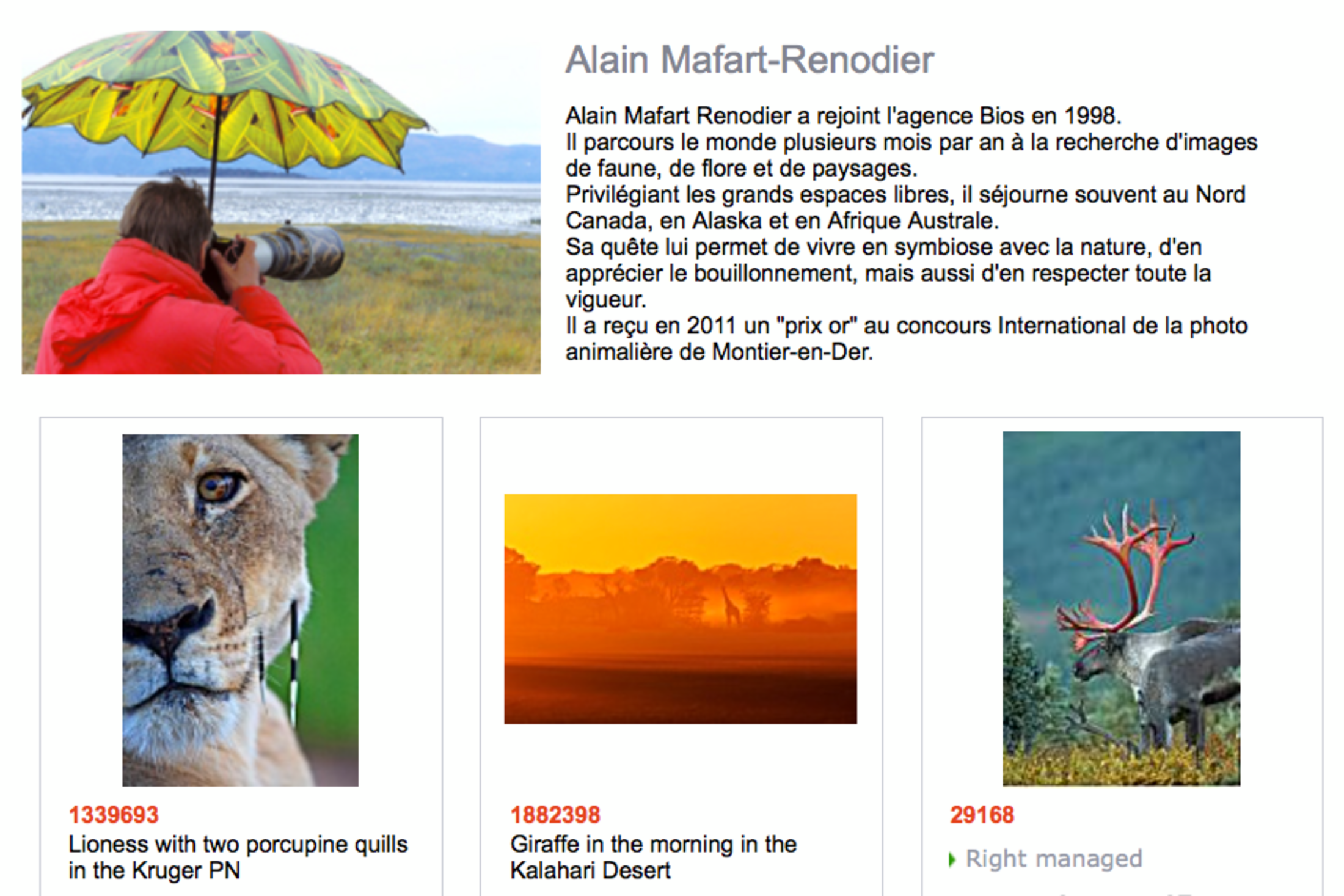

In this whole, unlikely story there is one final irony. Alain Mafart, who coordinated the secret operation in New Zealand, was arrested by the police in Auckland along with the woman posing as his wife, Dominique Prieur. At first imprisoned in New Zealand, then detained on the French military base on Hao atoll, east of Tahiti, Mafart only returned to France in December 1987. Eight years later, in 1995, he left the army to devote himself to what was already his true passion and to make it his new career: animal photography (see here). This involved a passion for nature, its preservation, its diversity – in short, the environment.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter