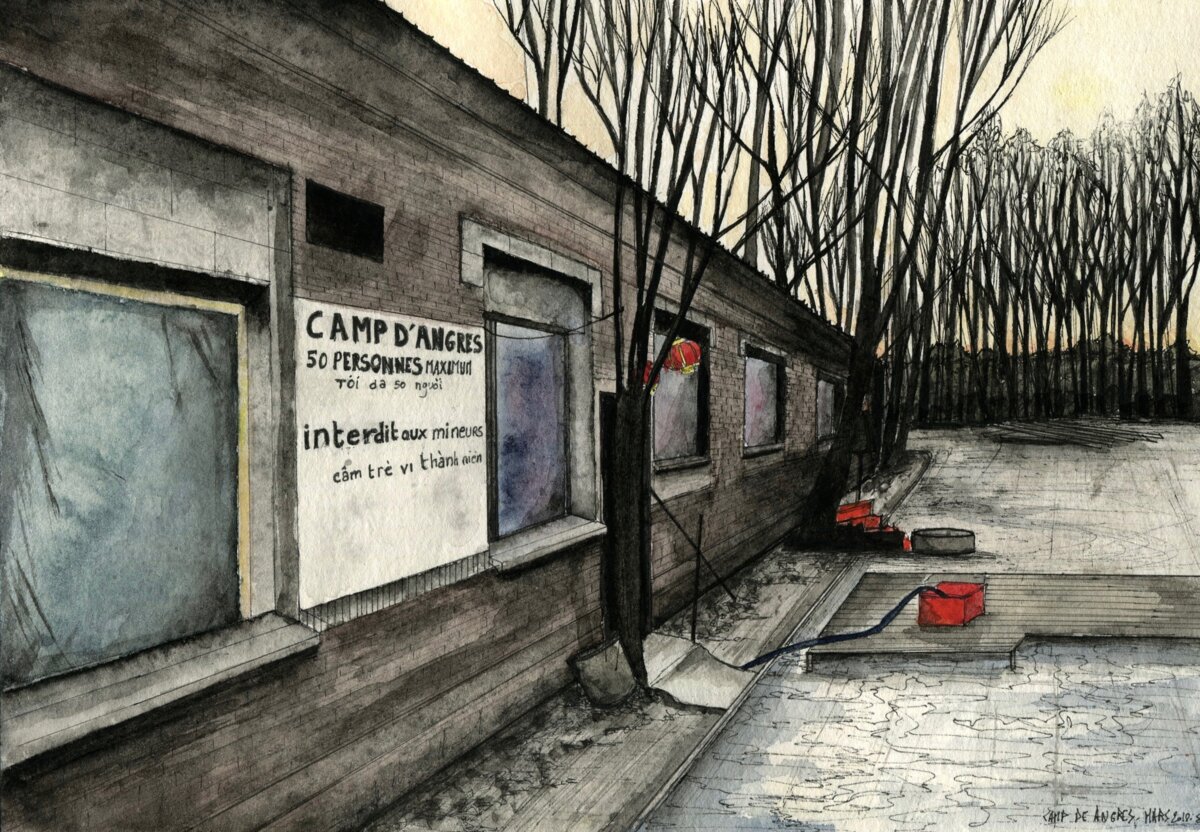

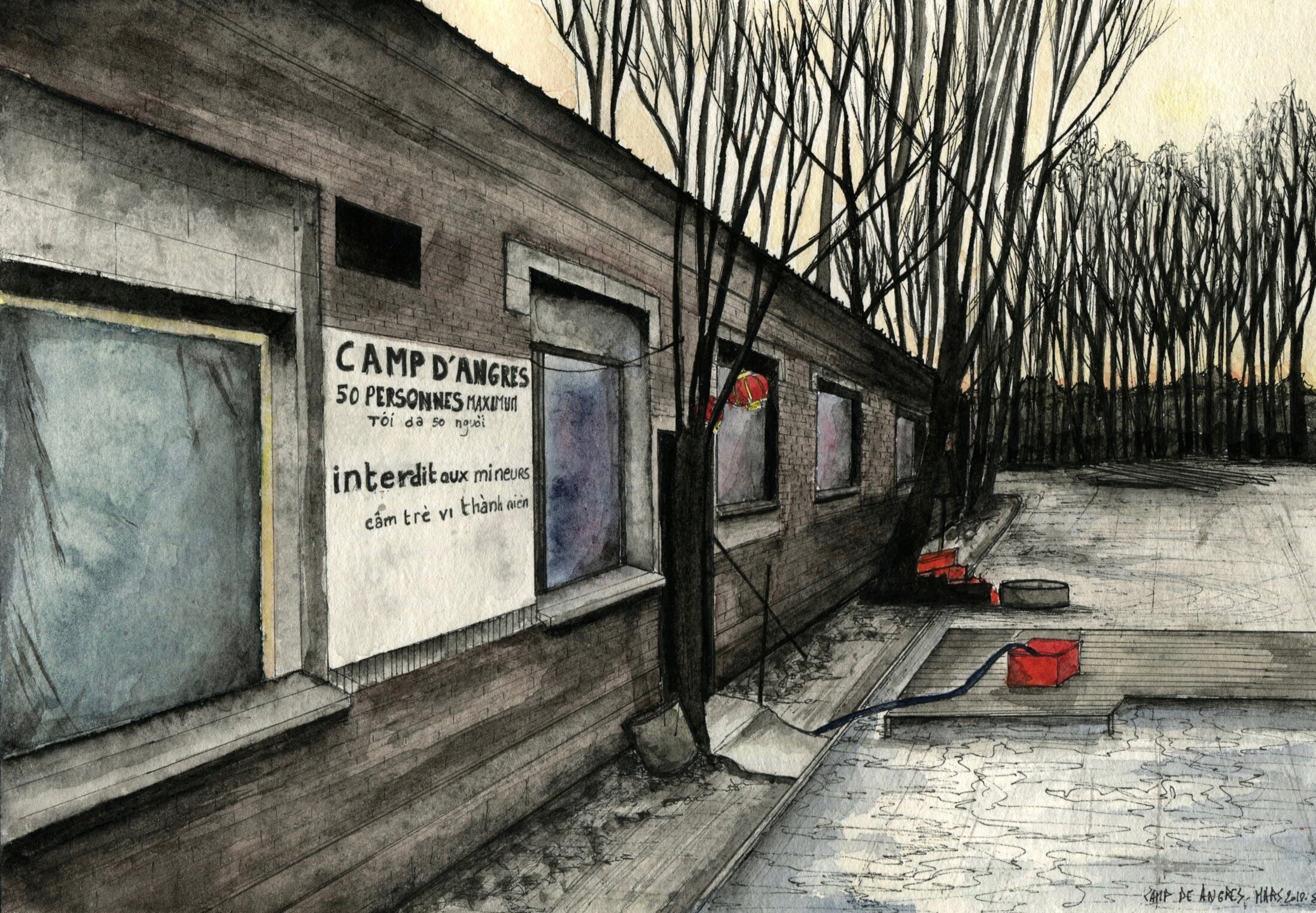

Dusk is falling over the brick building, the red Asian lanterns are shimmering in the cold while a light illuminates the shed next door. Silence reigns despite the fact that there are around 30 people here killing time on this cold evening on February 20th. A few hooded silhouettes are warming their hands while two men are chopping logs with an axe. Others stand smoking around a wood-burning stove in a sleeping area with walls daubed with colourful graffiti and where electric cables hang from the ceiling.

In a few hours, when night has fallen on the wood that is next to the camp, these men will walk the few hundred metres that separates them from the BP service station on the A 26 motorway, known locally as the 'English motorway'. These Vietnamese will then try, as they do virtually every night, to hide themselves aboard one of the parked lorries before its heads off to cross into the United Kingdom the following morning.

The camp is located at Angres, a small former mining town on the motorway some 100 kilometres from Calais and the English Channel. Its attraction for migrants is that the BP station is the last but one service station before the port city. The unofficial camp has been here since 2010 and now houses only Vietnamese migrants, earning it the nickname of 'Vietnam City' among locals. But few locals or indeed anyone else venture inside this secretive camp which is located behind old council workshops.

On the evening when Mediapart visited the men in the shadows at first held back, though one young man approached, smiling. He was one of the few there to speak English. He comes from the Hanoi area and explained how it had taken “three months to cross Europe”; a stop in Ukraine followed by Germany and finally Paris before arriving at Angres and its population of 4,000 people three weeks ago.

But the slim young man in a grey hood did not have time to finish his story or describe his hopes of what he might do in the United Kingdom. For a circle of other men had now gathered, with some men looking at him watchfully. The young man became on edge, and small wonder. As the authorities and the local volunteer groups acknowledge, the people traffickers themselves sleep at 'Vietnam City' and live next to those whom they regard as their “clients”.

The camp, which is also bordered on one side by a small chemical plant, is the final stop for all Vietnamese economic migrants who have crossed Europe illegally. They arrive here having paid between 15,000 euros and 30,000 euros for their journey. “They generally come from Russia where they arrive by aeroplane,” says Vincent Kasprzyk, captain of one of the BMR mobile investigation units in France's border police based at Coquelles near Calais. “From there the Vietnamese then make their way across land borders to France.” This means crossing Belorussia or Ukraine, Poland, the Czech Republic and Germany by foot or on the back of a lorry.

On the faded ochre exterior of the main building at the camp a sign says in French and Vietnamese: “Angres Camp, 50 people maximum, forbidden to minors”. “Generally there are about 10% to 15% who are under 18, 20% women and 80% men, quite young,” says Mimi Vu from the Vietnam-based NGO Pacific Links who has come to the camp several times. It is rare to find families here.

Depending on the period, between 70 and 150 people usually sleep inside the building provided by the communist-run local council. It is difficult to be precise because there is a fast turnover of migrants at the camp. “We've seen thousands of Vietnamese in recent years. It's never the same people after a few months,” says Benoît Decq from the local collective Collectif Fraternité Migrants Bassin Minier 62, which has supported these migrants for nearly a decade and has won their trust.

The traffickers change as well as the migrants, and new people arrive each month to replace those who make it across the Channel. “The port authorities at Calais can find up to 20 to 30 Vietnamese several nights a week,” says Julien Gentile, head of the Office Central pour la Répression de l'Immigration irrégulière et de l'Emploi d'Etrangers Sans Titre (OCRIEST), the police unit that fights against people trafficking. “And the police can't intercept them every day, so we think there's major trafficking between France and England. This major activity is very surprising as the camp is small compared with the number of presumed crossings.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It is a highly organised business. “There are several networks inside the camp, sometimes four or five,” says Julien Gentile. These traffickers advise their “clients” to be wary about local people and not to say anything. Because these “caretakers”, as local groups dub them, are on the lookout. They have organised the passage from Vietnam to the UK meticulously and do not intend to let go of their indebted migrants.

Unlike other migrant groups present in this part of northern France – Kurds, Afghans, Eritreans and Sudanese – the Vietnamese “don't pay the traffickers in advance but work along the route, in restaurants, textile factories, to finance their journeys as they go,” says Vincent Kasprzyk. An example was Cam, 32, who was interviewed for a report by the charity France Terre d'Asile in March 2017 and who described how he had worked three months in a restaurant in Warsaw for the “Vietnamese diaspora” before paying for his journey to Paris.

At the end of their long journey the Vietnamese are left at Angres – whose name they are often completely unaware of – by taxis registered in Paris, says Captain Kasprzyk. “Their fares are up to 600 euros for this. Finally, crossing the the final frontier at Calais costs up to 10,000 euros,” he says.

The migrants agree to undertake this long and difficult journey because of the promise of work in the supposed El Dorado of the UK. “These migrants come from poor regions in the centre and the north: the provinces of Nghê An, Hà Tinh, Quang Binh … there's no work for them and they have a culture of economic migration,” explains Mimi Vu of Pacific Links. “Their objective is to earn money to send to their family. The traffickers guarantee them they're going to earn between 1,500 and 2,000 pounds a month, so they agree despite the cost of coming. They tell themselves they will pay it back and that they can also send 1,000 pounds to their relations.” Many are aware they will be working illegally. But none of them at Angres know the real fate that is awaiting them across the Channel.

How Vietnamese traffickers 'won' the battle for Angres

In the camp the Vietnamese have become used to the discreet presence of the Collectif Fraternité Migrants Bassin Minier 62, who say they are there simply to “support these Vietnamese people”. As far as Benoît Decq is concerned they are victims. “Of course there are some crappy trafficking networks inside the camp and we must help these victims of trafficking,” he says. “That's why members of our collective take them all to have a shower at the weekends [editor's note, the camp has a house, a shed and toilets but no shower], bring them wood, try to communicate with them with hands, Google translation … however, the migrants do their shopping themselves with their own resources.”

In the shed a disco ball has been hung above some long tables and there is also some tinsel. “We organise meals with them, such as for the Tết festival [editor's note, the Vietnamese New Year, which was on February 16th],” explains Benoît Decq.

As far as the local council which has provided the site is concerned, having this unofficial camp represents the lesser of two evils. “Camps have been growing in number since 2006, the Vietnamese lived in the woods around the fuel station, it was difficult to control,” says one anonymous source. “At least they now have a roof. And if it were ever dismantled another camp would be created somewhere else in the town.” In fact, Angres has been one of the most coveted locations for the trafficking mafia since the end of the 1990s.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

On February 6th, 2018, officers from the OCRIEST police unit discovered an underground world at the site. In the course of an anti-trafficker operation of the kind they mount virtually every year in the camp they found a hole in the ground in the woods a few hundred metres from the camp itself. A cable attached to a tree trunk enabled people to abseil into the depths. Three metres down were red brick tunnels, dating from mining days, which led into caves. One of the abandoned tunnels led right under the shed in 'Vietnam City' itself.

Officers arrested seven suspected traffickers during that February raid. In all the police took away 35 Vietnamese, including four children and eight minors. But according to the authorities the tunnels could have been used to hide migrants during other police operations. They found some 14 lookout posts on the wooded walk from the site to the BP fuel station.

Such logistical measures shows the level of organisation at a site guarded like a fortress. Why is it so protected and coveted? The reason is the proximity of that BP service station which because of its strategic location acts as a magnet for people traffickers. As the last but one stop before the port at Calais or the Eurotunnel, many lorries park there – providing an opportunity for migrants to stow away.

The Vietnamese “won” this service station after a long “parking zone war” in the middle of the 2000s. At the time various trafficking gangs fought over different service stations in the region, with the conflicts sometimes degenerating into armed confrontations. “The Vietnamese arrived in France around 2002, and they had a parking area on the motorway to Belgium but the prefecture [editor's note, local state authority] closed it,” says Captain Kasprzyk. “They later came down to Angres.” The BP service station had for a period been “owned” by an Albanian trafficker who was then killed by an Iraqi Kurd trafficker called Ali Tawil, who wanted it for himself. Forced to flee to Belgium after the killing, Ali Tawil left the place under the control of his “lieutenants”. They did not resist for long against the Vietnamese, who took over the patch within the space of a few weeks.

However, other groups still coveted the strategically valuable location and in 2009 Chechen gangs tried to replace the Vietnamese. But they failed and the latter have controlled the area for a dozen or so years despite the efforts of other gangs and police anti-trafficking operations. “Today there's a more closed atmosphere than there was a few years ago,” accepts Benoît Deck. “After the [police] raids it's hard for us to go and speak to the Vietnamese, the leaders have become more suspicious.”

Violence has recently broken out at the camp too. Five Vietnamese were attacked on the afternoon of March 30th. According to a police source four received knife wounds, one suffering more serious injures to his back and legs. A fifth Vietnamese suffered bruising. The authorities do not yet know the identity of the two assailants.

Cannabis farm slaves

The migrants staying at Angres are discreet. When they finally arrive across the Channel many become ghost-like figures, working at night as slaves. A report on modern day slavery and human trafficking by the UK's National Crime Agency, which analysed the period from October to December 2017, noted that Vietnamese nationals are among the three most exploited groups in the UK, after Albanians and Britons.

“All the migrants that I've met at Angres and Coquelles had thought they'd working in a nail bar,” says Mimi Vu from Pacific Links. In December 2016 immigration officers in Britain visited more than 280 nail bars in London, Edinburgh and Cardiff as part of Operation Magnify which targeted industries seen as being at “risk” from modern slavery and illegal immigration. The BBC reported that “most of the 97 people held were Vietnamese nationals”, all of them on suspicion of immigration offences.

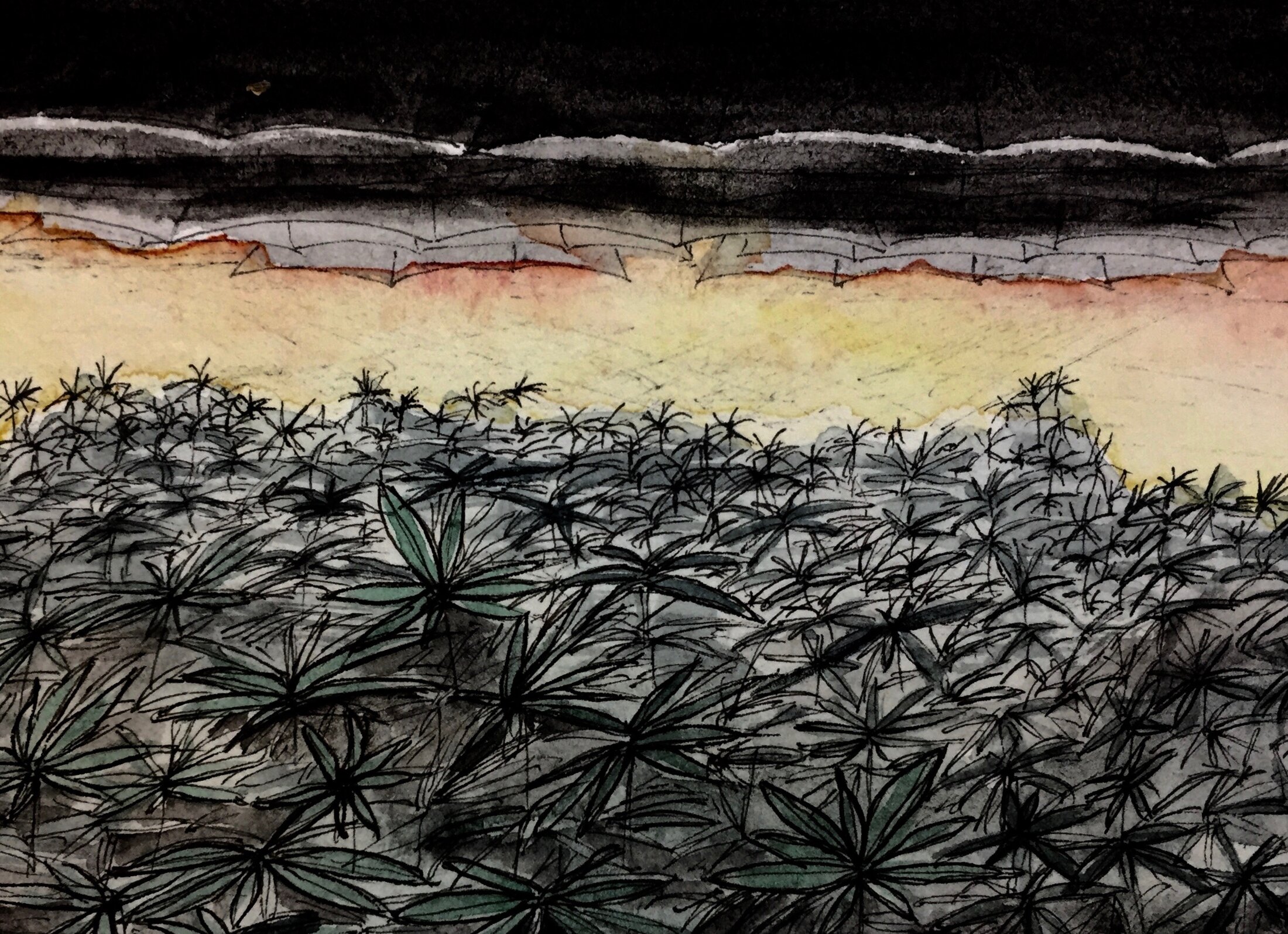

The other main worry for the authorities and charities concerns the trafficking of Vietnamese migrants to work in indoor cannabis farms. This is a massive and often literally underground business that involves the use of hidden cannabis farms or factories all over the UK, which are regularly uncovered by the police. “It's Vietnamese mafia groups who dominate this market,” says Mimi Vu. The other two main nationalities involved are Albanians and Britons themselves, according to ECPAT UK, the children's rights organisation working to protect children from child trafficking and transnational child exploitation.

These Vietnamese gangs enslave other Vietnamese. “Migrants say during their journey they will be working in nail bars but in reality when they turn up it's in these farms,” says Mimi Vu. In 2014 and 2015 some 366,841 cannabis plants were seized in England and Wales, or more than a thousand a day, according to a report by the UK's Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner citing figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

On February 23rd, 2017, police in Wiltshire in the west of England discovered a cannabis farm that had been operating in an old nuclear bunker dating from the 1980s. The several thousand cannabis plants were being grown in 20 different rooms and the police estimated the street value of the plants they found at more than a million pounds. Four Vietnamese workers, including three teenagers, had been working at the site as “slave labour”, said the authorities.

According to ECPAT UK's head of advocacy, policy and campaigns Chloe Setter, the existence of such farms first came to public attention around 12 years ago “when a Vietnamese child was found in one of them”. The organisation has been in contact with many former cannabis 'gardeners', some of them orphans taken from their country of origin. The exact conditions in which they are forced to work in this clandestine industry are not fully known. Some are locked in, often sleeping on the floors of the cannabis factories, others are in rented flats, and controlled through fear. They look after the cannabis plants which require precise watering and carefully-calculated temperature and light levels. They work all hours, exposed to risks in dilapidated buildings with makeshift electricity supplies.

The traffickers use their victims' outstanding travel debts to keep control over them. They accommodate the migrants but do not stay on site with them. “In the initial months the traffickers don't pay them, telling them they are giving them free accommodation and supplying their food … then the young people start to work to pay off the journey but given what they earn they never reach the sums spent,” says Chloe Setter. The workers rarely go out and when they do they are usually accompanied by a trafficker.

The young people earn little, “sometimes ten to 15 pounds a month, sometimes 300 pounds for six months, sometimes nothing,” says Chloe Setter. Pressure is also sometimes put on their families back home to help repay the debt. “No one dares to escape, the traffickers tell them that without documents they'll end up in prison and will no longer be able to pay them. Moreover, these young people continue to hope they will earn money, thinking it's humiliating not to be able to send anything to their family,” she adds.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

From the traffickers' point of view it is a winning formula; there is very little risk and the profits are enormous. They are often absent when the workers are arrested during operations to shut down factories.

ECPAT UK is now fighting to get these young Vietnamese recognised as victims of slavery. In October 2017 the organisation released a short animation film The Secret Gardeners to highlight their plight. In it a teenager describes his confinement in a cannabis farm. When he was arrested by the British police the Vietnamese youngster was accused of lying about his age and of being a criminal, and said he “didn't understand” what was happening to him. According to ECPAT UK there were 227 Vietnamese children identified as potential victims of modern slavery in the UK in 2016. But demonstrating this status is a complex process; in the UK as in France, migrants typically say nothing. The traffickers tell them to keep quiet if they are arrested, explains Chloe Setter.

The Secret Gardeners also aims to create awareness among another group – people who smoke cannabis. “The consumers don't know that their cannabis comes from slavery,” points out Chloe Setter. “This phenomenon doesn't just affect England. We know that cannabis farms also exist in the Czech Republic and Germany. We've carried out investigations, too, in France.”

In fact, a number of cases of indoor cannabis growing have been uncovered in France, including at a disused fashion workshop in La Courneuve north of Paris in 2011, a house in Saverne in north-east France in 2012 and a small house in Tremblay-en-France north of Paris in 2014. On each occasion it was Vietnamese nationals who were behind these illegal 'farms'.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter