Dairy farmer Sébastien Le Bodo guided his small refrigerated truck along the snaking country road, passing by a succession of woodlands and glades. “In that hangar you have 5,000 pigs,” he points out as we come level with the entrance to a farm close to his own. “The thing’s crazy.”

Le Bodo’s farm is situated in countryside near to the town of Vannes, in the Morbihan département (county) of south-west Brittany where, surrounded by widespread intensive farming, the organic farmer is one of a tiny minority. “We’re from the same race, farmers, fanatic about the land,” he says of his neighbours, “but, in the end, we don’t practice the same profession anymore.”

He decided not to join the mass demonstration by farmers in Paris on September 3rd, when hundreds of tractors converged on the capital in protest at their diminishing incomes, modest, and for some dire, living conditions in a display of force largely organised by the biggest French farmers’ union, the FNSEA. He chose not to because he is opposed to the FNSEA’s policies, which include support of intensive farming, campaigning for an extension of state aid packages for farmers and its vision of modernizing French farming to keep pace with the mass production of rivals in Europe (a spiral underlined this Monday with the announcement that the European Union is to grant a continent-wide package of 500 million euros of emergency aid for struggling farmers).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But another reason for not joining the protests is that Le Bodo is not in financial difficulty. Every month, he pays his mother and sister at least the minimum legal wage (which is 1, 457.52 euros per-month before deductions) for their work on the farm which, unlike so many others which centre on high-volume production alone, is economically viable.

Le Bodo produces yoghurts and soft cheese - fromage blanc – for group caterers in the region. A member of the Confédération paysanne, the French farmers’ union that notably campaigns for an environmentally-responsible approach by the profession and against intensive farming, he is one of about 4% of Breton farmers who have adopted practices aimed at maximizing the alimentary independence of his business. “When you have 96 percent who say the opposite of the message you’re trying to get across it’s complicated,” he says.

He is one of a handful of farmers in Brittany who manage a successful business by using simple methods that are the opposite of those of intensive farming: small agricultural holdings, with short, or local, commercial channels, the production of finished products (in his case cheeses and yoghurts) on the farm itself, the exclusion of chemical phytosanitary products and a diverse clientele.

Pierre-Yves Floch is a pig farmer based just a few kilometres from Sébastien Le Bodo. “My colleague Jean-Michel, who is also my neighbour and friend, was strangled by the conventional farming system,” recounts Floch. “He took over his parents’ farm, but it wasn’t profitable enough for the [commercial management] integrator, a big cooperative. He would have had to borrow 800,000 euros to be able to modernise his structure and to produce more pigs. So we chose the opposite, and converted his building above ground into an organic piggery.”

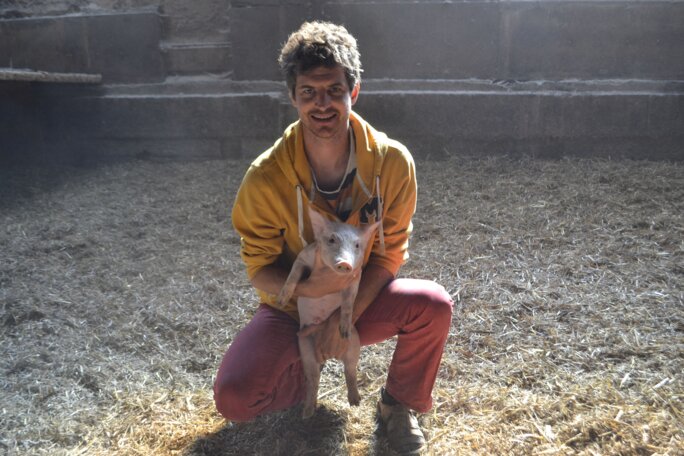

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Floch struggles to catch his breath as he talks, after chasing after a piglet to appear in a photo (above), proof in itself that this pig farmer is not one who rears in mass to sell his animals to the marché du cadran in Plérin. Situated in Brittany, where 60% of all France’s pig farms are situated, this central pig auction market sets the benchmark price of the animals.

Floch’s piggery, modified after he and his friend Jean-Michel set up their small business in common - a legal entity called a Groupement agricole d’exploitation en commun (GAEC) – meets the strictest demands for the “organic” appellation, including adequate space for the animals to run around in, straw covered ground, openings to let in natural light and access to the outside.

He has no business with the pig trade that competes with the mass piggeries of Spain or the Netherlands. During the recent crisis, conventional French pig farmers protesting against the ever-lower prices paid for their animals demanded the imposition of a minimum pre-slaughter price of 1.40 euros per kilo, which was rejected by some of the industry’s major meat processors. Floch, meanwhile, sells his animals at 3.5 euros per kilo.

'Conventional farming is not viable'

The methods employed by Pierre-Yves Floch are based on the pillars of what the Confédération paysanne describes as ‘l’agriculture paysanne’ (the largely bygone traditional agricultural methods of small farmers). Among these is the decision not to buy in food for his animals, all of which is produced on the farm itself. “On our land we grow wheat, faba beans, peas, oats, triticale and [we have] seven hectares of corn,” details Floch.

He and his associate Jean-Michel have no plans to expand their business. Floch’s farm has a permanent number of just 28 sows, compared with the several hundred sows that count average piggeries in the region. Many of the conventional pig farms sell their parallel cereal production to the commercial pig industry networks, called ‘integrators’, who provide a complete umbrella of services for piggeries, such as Cooperl, and then buy back granulated swine-feed for their animals. “When you are ‘integrated’, you are told what to give to animals, at what time, when they’re to be sent off by truck, when to invest, which bank to borrow from,” says Floch. “And then you are told, ‘ah, there’s an embargo, a flare up in Ukraine, the price has changed,” he added, referring to the significant loss in demand for French pork after EU sanctions against Russia were imposed for its support of separatist rebels in south-east Ukraine.

Floch is free to fix his own price for his animals because he works within a short commercial chain. “Our animals are slaughtered in Vannes and we have the meat transformed by a butcher we employ a few kilometres from here,” he explains. “Then, in shops of producer goods or on [stalls at] markets we sell fresh sausages, pâtés, rillettes and so on.”

Nevertheless, some of the meat from the 400 pigs he slaughters every year is sold through more distant commercial channels, namely the organic cooperative Bretagne Viande Bio (BVB), where the prices are established on a yearly basis, as opposed to the weekly fluctuations of the conventional pig trade.

The pride he has in having created a viable economic model is also felt by another of his friends, Jean-Charles Metayer, an organic poultry farmer. “I do everything,” explains Metayer, “I’m a breeder, crop farmer, slaughterer, [meat] processor, advertiser, delivery man. I work 70 hours per week.” Metayer has a modest income, about the equivalent of the French minimum wage, but which he has been able to pay himself uninterrupted ever since he began his organic business in 2007. “We turn in a surplus balance every year, with one employee,” he says. “Our farm can allow two people to live full-time.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Metayer’s birds run and flap around their vast enclosures, apparently oblivious to the cold and persistent Breton drizzle falling from the grey skies. Like a picture from a children’s book, the farm is dotted with chickens, geese and ducks, while in a meadow just beyond are several ewes.

He dons sterile feet caps and a jacket to present what he calls his “lab” where 500 birds are slaughtered each month, with some of the meat transformed into prepared dishes of ‘foie gras pâté’, or chicken rillettes ‘à la sauce forestière’, or Barbary Duck foie gras. “The transformation allows for a triple valorisation of the product, against a single one if we sell the chicken on a long commercial channel,” says Metayer, who sells his products on local markets and also via his internet site. None of Metayer’s poultry production goes to supermarkets.

Sébastien Le Bodo is convinced that the model of farms which sell to a close-proximity network of clients can still be viable as a generalised system, and not limited to a small minority of farmers. “It would suffice that consumers change their manner of going about things,” he says. “In any case, the conventional farming model is not viable, that we can see clearly.”

That view is shared by sociologist Véronique Lucas, who is currently completing a thesis on the question of new forms of economic cooperation in French agriculture for the country’s National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA). “Since the 2008 financial crisis, there is an underlying movement among conventional farmers towards alternative models,” argues Lucas. “They’ve seen the limits of their model. This wave is not quantifiable because the statistics are badly put together, but I’ve witnessed throughout my research that a large number of farmers in France have developed strategies so as to be no longer dependent upon the market prices of raw materials such as colza. For the alternative model to develop from that is just a step away. Because the agroalimentary industry has forced a fair number of players in the sector to align themselves upon [certain types of] animal breeds, standards, practices. An alignment on the alternative model, supported much less by public policies, will be a long-haul movement.”

Sébastien Le Bodo agrees. “In any case, it would surprise me greatly if the whole of Morbihan farmers converted to organic [farming] and left their ‘integrated’ chain in one go,” he says. “There are so many obstacles. Most of them have inherited the system from their parents, in the same way that I took over my mother’s farm. It wasn’t easy to tell her, with my sister, ‘we’re going to do differently to what you’ve taught us for 40 years’. Since we set up [as organic dairy farmers], we’re just four [such farms] in our département.”

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse